It’s easy to forget that, in an era of unprecedented access to information fueled by an accelerating Moore’s Law, everything weighs on the land. While unlikely to be visible from the backyard, the infrastructure of digital technologies will only become more pervasive, and should be respected with the same aesthetic and critical discourse that we bestow on the ballet of the sidewalk, the symphony of the city, and the poetry of infrastructure.

Harvard’s New Geographies 07: “Geographies of Information” tries to move past the simplistic binaries limiting geographic discussions of information and communication technologies (ICTs): global or local, physical or virtual, hardware or software. Instead, “Geographies of Information” confronts the many ways in which the “forms, imprints, places, and territories of ICTs”—data fueling speculative real estate, political protests through social media, architects' surveying visualizations, server farm compounds—weigh upon our lived world.

Distinct from the Harvard Design Magazine, New Geographies is run by doctoral candidates at the GSD’s Urban Theory Lab, and supported partially by grants from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

Our featured excerpt focuses on the mammoth, but rarely seen, defensive structures that manage massive data trafficking—illustrated by the NSA’s hub in Bluffdale, UT (“the daddy of all security data centers”), and Walmart’s Jane, MO data mining center. Written by Stephen Graham, professor of cities and society at Newcastle University’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, the piece offers a fascinating look at the co-dependencies between financial and security systems in today’s economy, and their impact on the land.

Stealth Architectures and the Geographies of Backup

by Stephen Graham

In the summer of 2004, a vast, squat, and anonymous building was completed next to US Route 71 on the edge of the unprepossessing Midwestern town of Jane, Missouri. Apart from a complete lack of the usual corporate signage and iconography, this 133,000-square-foot structure is virtually indistinguishable from the countless other suburban distribution centers that colonize the vague margins between urbanity and rurality which encircle the world’s towns and cities.Walmart is only the largest and most spectacular of a whole new field of stealth data-center architecture—what London architectural critic Martin Pawley called “terminal architecture”

“There is nothing about the building to give even a hint that Wal-Mart owns it,” writes Max McCoy for the Joplin Globe. “Despite the glimpses through the fence of manicured grass and carefully placed trees, the overall impression is that this is a secure site that could withstand just about anything.” The center was deliberately placed on solid bedrock and is designed to withstand powerful local thunderstorms, earthquakes, and terrorist attacks. “Earth is packed against the sides,” explains McCoy. “The green roof—meant, perhaps, to blend into the surrounding Ozarks hills—bristles with dish antennas. On one of the heavy steel gates at the guardhouse is a notice that visitors must use the intercom for assistance."

Rather than orchestrating the physical transportation of products, this center operates at the heart of an equally vital but far less visible process: the continuous flow of digital data. The US Route 71 complex is the epicenter of Walmart’s global architecture of data traffic—an assemblage developed specifically to ensure that the 100 million-or-so apparently mundane digital transactions, communications, and surveillance events that sustain the world’s largest retailer each day carry on, relentlessly, no matter what extreme events, malfunctions, or acts of political aggression target the firm’s operations.

Architectures of Anticipation

The center concentrates, and backs up, all data captured across the firm’s stores and online transactions worldwide. This process allows sophisticated data-mining software to predict market trends, thus allowing the global chains of production and distribution to synchronize as nearly as possible with changing market geographies as they play out.

As Hurricane Frances bore down on Florida in the summer of 2004, for example, Walmart’s data-mining center quickly analyzed consumption patterns from similar previous events. It predicted that local stores would need large quantities of a range of products beyond the obvious torches and candles. “We didn’t know in the past that strawberry Pop-Tarts increase in sales, like seven times their normal sales rate, ahead of a hurricane,” Linda M. Dillman, Walmart’s CIO, said in a New York Times interview conducted at the time. “And the pre-hurricane top-selling item was beer.” Thanks to those analyses, large loads of these items were soon speeding down highways toward Walmart stores located in the projected path of the hurricane.Meanwhile, in the downtown cores, disused and obsolescent modernist tower-blocks have been converted into so-called telecom hotels.

Stealth Data Architecture

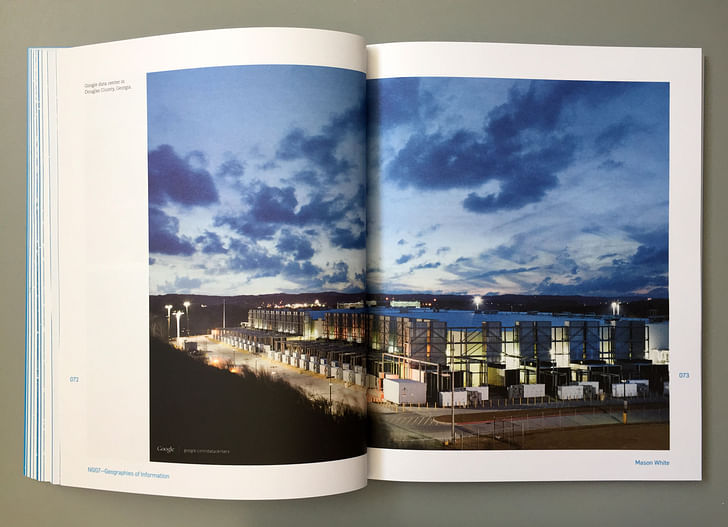

Walmart is only the largest and most spectacular of a whole new field of stealth data-center architecture—what London architectural critic Martin Pawley called “terminal architecture” in his 1998 book of the same name. Such buildings are springing up in the most unlikely locations, spreading a whole incipient geography of backup and repair across the world. Near the core of global finance epicenters such as London and New York, for example, bunker-like business continuity facilities cluster, ready to go into operation to support corporate data flows and archives whenever the main corporate headquarters or electronic trading floor faces a disruption of any kind. Areas adjacent to corporate and financial downtowns, such as London Docklands and New Jersey, are now chock-full of such fortified centers, and the specialized firms that operate them now constitute an important economic sector in their own right.

Meanwhile, in the downtown cores, disused and obsolescent modernist tower-blocks have been converted into so-called telecom hotels. Their windows blacked out, these structures house web servers and major digital switching systems connected directly to the planet’s fiber-optic grids. They allow the world’s major communications providers to serve the world’s major metropolitan markets cheaply, efficiently, and with minimal vulnerability to disruption.

Far away from these metropolitan hubs, data backup and storage centers increasingly occupy the world’s nooks and crannies. The accumulated regolith of military architecture, abandoned since the late twentieth century, offers prime real estate for reconstruction as data centers. Abandoned military bunkers, especially, lend themselves to repurposing as ultrasecure data archiving and backup facilities. In northern Washington, DC, for example, a missile control bunker from the early years of the Cold War has been turned into an ultrasecure data center known as “Titan 1.” An abandoned intercontinental ballistic missile silo near Albuquerque, New Mexico, has been similarly retrofitted. In Europe parallel refits have been completed using World War II antiaircraft forts off the coast of South East England and civilian antinuclear bunkers deep below the Swiss Alps.

Big Box, Big Data, Big Brother

To the list of corporate data centers we should also add, of course, the burgeoning data collection, surveillance, and “fusion” centers of national security states, emboldened by the rapidly extending “national security” initiatives resulting from the global “war on terror.” In such complexes, the commercial innovations of data mining, communication tracking, and profiling are now mutating into new assemblages directed at social and political control. Often such operations blur troublingly with protocols like Walmart’s, for the very commercial firms that specialize in such tasks for corporate clients are taking up the mantle of national security data mining as they take advantage of the contracting opportunities created by privatized and neoliberal states.

The daddy of all security data centers is the US National Security Agency’s hub in Bluffdale, Utah. The nexus of a vast, global data-intercept cloud that dwarfs even Walmart’s, the center seamlessly links together the world’s most powerful supercomputers, satellites, and transnational snooping systems with primary transnational telecom and internet service providers. It has been estimated that the NSA intercepts 1.7 billion items of data per day and harvests 2.1 million gigabytes of data per hour. They then pour this data into the largest server banks on Earth.So anonymous are these buildings, so ubiquitous and generic their urban or suburban presence, they are rendered invisible

Imperatives of Backup and the Always-On Economy

All of the world’s major telecommunications outfits now operate their own large-scale bunker complexes. These are designed to allow for the automatic or near-automatic repair of data and communications networks in the event of catastrophic events such as the 9/11 attacks or Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. With their room-sized digital world maps displaying real-time events, monitored by operators in tiered ranks, these bunkers look more like the nuclear weapons control rooms of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) than sites dedicated to managing more mundane threats involving automatic teller machines, mobile phones, supermarket checkouts, gas pumps, and internet “network unavailable” messages.

In a global, digital, twenty-four-hour economy, the absolute imperative is to ensure continuity of service and connectivity. For e-commerce firms, financial services corporations, worldwide logistics and transport providers, call centers, and international information and consumer data companies, continuous data flow and archiving are, very literally, the only possible means of operation. The costs incurred when the data flow is disrupted quickly lead to the very erasure of these firms. Neil Stephenson, CEO of the Onyx Group—a major developer of business continuity centers—commented in 2006 that, according to statistics produced by the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister in the United Kingdom, 80 percent of businesses affected by a major incident that disrupts their digital operations or erases their database archives close within eighteen months of the event.

It is not surprising, then, that in the remote and bunkered spaces of the post–Cold War landscape, a new brand of stealth architecture is mushrooming. So anonymous are these buildings, so ubiquitous and generic their urban or suburban presence, they are rendered invisible—undiscoverable except by a handful of hardcore infrastructure enthusiasts and researchers of the urban esoteric, impenetrable by all but a few highly skilled hackers.

Still, these built architectures remain more manifest than their vital, digital shadow. The backup and repair centers perform the powerful job of hiding data infrastructures—the fibers, servers, programs, and code—that link together the interstitial economic geographies of the world. Most invisible of all is the growing universe of software that automatically detects, diagnoses, and attempts to repair interruptions to flow and connectivity within transnational data systems, routing traffic away from failing nodes within the Internet’s famous “packetswitching” architecture and backing up data records on the most secure sites, housed within transnational networks of linked data centers. Together, these spaces and systems constitute what we might call the global assemblage of digital flow. The most crucial infrastructure of globalization, this pervasive digital skein of communications systems works continually to bring the global digital economy, with its mobilities and flows, somehow magically into being.the invisibility of global data systems in everyday life means that they are only really noticed (and then, only fleetingly) when they cease to function.

And yet, like all true infrastructures, the invisibility of global data systems in everyday life means that they are only really noticed (and then, only fleetingly) when they cease to function. At such moments, the constant calculative operations sustaining global digital capitalism momentarily materialize, until reinstatement occurs and the assemblage sinks into the background once again.

Such a perspective has clear analytical implications. It suggests that it is best not to see the so-called network or information society as some extraterrestrial impactor, miraculously transforming cities and societies in its wake. Rather, we would be wise to stress that such transformations are the result of new systems, built spaces, and digital architectures and practices having been brought into being and sunk anonymously, and often invisibly, into the places of the world.

If we were to pay more attention to the mundane infrastructures, landscapes, and assemblages involved, and the ways in which they quite literally surround and sustain our everyday lives, we might be less likely to wrap these transformations in the hype of utopia—or dystopia—with all the unhelpful gloss that doing so invites.

New Geographies 7, edited by Ali Fard and Taraneh Meshkani, also features pieces by:

Jean-François Blanchette, Caitlin Blanchfield, Benjamin H. Bratton, Erle C. Ellis / Michalis Pirokka / Peter Del Tredici, Ali Fard / Taraneh Meshkani, Mark Graham, Stephen Graham, Adam Greenfield, Shuli Hallak, Evangelos Kotsioris, Merlyna Lim, Eleonora Marinou / Yannis Orfanos / Spiro Pollalis / Vicky Sagia, Malcolm McCullough, Dimitris Papanikolaou, Antoine Picon, Mark Shepard, Molly Wright Steenson, Kazys Varnelis, Mason White, Matthew W. Wilson, and interviews with Jennifer Light and Rob Kitchin.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured New Geographies 7, "Geographies of Information".

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

More on the invisible systems that permeate our daily lives, for good and for ill, can be found here, as part of our special June editorial theme of Privacy.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.