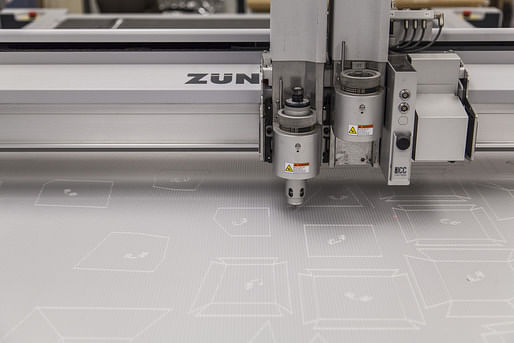

The newly renovated Digital Fabrication Lab (FABLab) at Taubman College leverages state-of-the-art industrial technology to perform architectural fabrication research. The FABLab at the University of Michigan is one of few select academic institutions around the world utilizing robotic automation to perform both subtractive and additive manufacturing processes. The technologies have existed in the aerospace and automotive industries for some time, but have just recently infiltrated the architectural-fabrication industry. The FabLab operates numerous computer-numerical controlled (CNC) machines, allowing students and faculty to work with virtually any material.

_____________________________________________________________________

Many students who attend the University of Michigan seek insight in expanding their knowledge in fabrication as it informs and aids their architectural education. Tafhim Rahman, a 1st year M.Arch student is amongst one of these students. Rahmin recently sat down with Aaron Willette, the FabLab Coordinator at Taubman College, to interview him on his path into digital fabrication and some of his thoughts on the matter as it pertains to architecture.

How did you get started in fabrication and digital fabrication in particular?

I kind of grew up in machine shops as both my father and paternal grandfather were machinists. One of my earliest childhood memories was being in the back of mother’s bicycle and going to visit my father at the tool and die shop he worked in and growing up there was always a workbench in the basement that my father and maternal grandfather would work from. Growing up in those environments I was always exposed to the type of conversations about that line of work but I was always told to never to be a machinist. In hindsight, that’s kind of funny.

But I knew at a fairly young age that I wanted to become an architect. My father had a lot of Frank Lloyd Wright books around and even though I didn’t really know what it was, from 8th grade on I knew I wanted to be an architect. Throughout high school I was taking drafting classes, and then in one of my art classes my teacher approached me, told me I was bored, and asked if I wanted to learn how to weld. They threw me over to the vocation wing into the welding shop and I started to really get my hands dirty. For some reason when I did my undergrad in architecture I wanted to shy away from that past and had the intention to get my Master’s degree specializing in theory.

So just out of curiosity, you wanted to go to school and study theory- what kind of theoretical school of thought were you interested in and if that find its way in your fabrication work and knowledge?

Yes, it definitely finds its way into my current work. One of my undergraduate studies professors pushed a lot of Frampton on us, and we read his Studies in Tectonic Culture at the beginning of our third year studio. That got me into thinking about the role of construction logics and regional cultures and how they manifest themselves in the built form. From there, I got turned onto Perez-Gomez and everything else. The desire to go into theory was kind of my way to rebel against the very pragmatic program that I was enrolled in, which at the time was more about training people to work in the industry and not necessarily be thinkers.

So do you see the work that you do now as a continuation of that “rebel” mentality or a rebellion against your younger self?

I see my interest in making as something that developed once I left academia and had some time to think about what interested me. One of the biggest mistake students make is going into graduate school immediately after their undergraduate studies because they’ve yet to have the time to really think for themselves. When you’re in school, you’re constantly working on other people’s agendas and you’re getting things pushed at you and I just needed time to figure out what was right for me. By taking some time off between my undergrad and grad studies, I gave myself the room to grow and develop my own opinions on architecture, culture, and technology. And I guess I landed back into the family trade!

Yeah, I find that me having taken two years off between undergrad and grad school is really great and got me back into tinkering with wood and what I am interested in now.

As a current student, I’m curious to know what are some future ambitions that you plan on bringing, or is pushing for, in the FABLab that would be beneficial for students?

One of the things that I have pushed is the structure of how the FABLab operates. I very much enjoy having schedules and protocols, only because the FABLab has grown into such a fairly large operation. We have approximately 30 work study students running the shop with me right now, so we need to have things in place so the shop runs smoothly and that everyone knows how to handle things safely.

I also think it’s about increasing accessibility. It’s impossible to train every student on every piece of equipment, but trying to have more available time for all of the students on the equipment is important. For example, the latest robotic work cell we’re adding makes the robots more accessible. Instead of having one big work cell, we now have multiple work cells where students and faculty can use this technology. Robotics has been part of my own interests here at the University of Michigan, so I’m interested in how we can make these technologies more accessible to students so they can take things in their own direction. But like anything, it just takes time to get everything up and running.

I know there are a lot of components in robotics and digital fabrication in which you need the knowledge of how tectonics and materials work, and of course there is tooling and all of those things. How do you package that information for other students when you give tutorials, or especially when you teach digital fabrication within just one semester?

Yeah I think that’s always a challenge. The course I taught last semester went under the theme of boot-strapping; trying to introduce students to the tools in ways that allows them to jump into projects quickly. You’ve been attending my Mastercam which are about getting students situated in the software and showing some best practices so they can start to explore on their own. It’s all about getting people moving and focusing on developing certain skills for certain types of application. In an introductory digital fabrication course I don’t think it makes sense from a coursework perspective to have design and fabrication and everything happening simultaneously in every project. I’ve found it’s important for me to strategically plan out and then expand upon those topics throughout the course of the making sure you have some technical ability before you start folding design and everything else that it brings with it into the mix. The beauty of being a faculty member here at the University of Michigan as a faculty member is that I can count on the fact that all of my students will have good design skills which allows me to focus on developing their technical before wrapping design back into the conversation. Because at the end of the day, if my courses aren’t including design, they’re operating more like a trade school, which is not what myself or the students are here for.

Are there specific ways that you establish the base components to allow a seamless integration with students into bringing that technical information into their design practice? To my knowledge, sometimes when you get into the design, the technical knowledge falls away.

I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing that some of the technical aspects falls off a little bit as long as the students retain some of the core skills. The only way to do that is to encourage students to take on the challenge of incorporating those skills into their design practice because like any task we do as designers, if they don’t sit down and dedicate the time to do it, they’ll never really understand it. Providing students with that opportunity is the most important step since, at least from my own experience, graduate school is about having the opportunity to tackle problems that we might not have had the chance to address yet and want to take on. Coursework is always developing, but I want to provide students an opportunity to find their own voice with the technology.

Have you seen any patterns or attitudes, or approaches that have led them to pick up the skills faster than others?

I find the thing that helps students work through issues the most is making them draw everything out first. Digital fabrication, or fabrication as a whole, deals with a lot of realities: materials, fasteners, and many other components. In the design studios, many people have the habit of glazing over some of those finer details. So forcing students to really look at the size of a screw and how it is part of the larger assembly, or what the thickness of their stock is important. To really understand how things come together you can’t design based upon what you think things are but what they actually are. It’s a strategy in which 3D modeling becomes extremely useful because a robust 3D model can help you to think through the logics of fabrication quickly without having to actually go through all the fabrication steps.

Are there ways that you plan on experimenting with the class structure or even with the FABLab to encourage the best environment for growth where all students pick up the knowledge in technology to incorporate into their designs?

Something that I picked up half way through the last course I was teaching is that a lot of what goes on in the FABLab needs to by demystified. A lot of students come here to the University of Michigan with preconceived notions of what goes on in the space which may or may not be true. Not everyone understands the machines and what they can actually do, so taking time early to walk the students through the space and explain the equipment early on was rally beneficial.

I know not every student will operate a CNC machine or robot professionally when they leave Taubman College, but I do think it’s important for every architecture student to know how to talk to the people who do and really understand what goes on behind the scenes. For example, if they are working with a contractor who has a CNC machine, I want them to have an intelligent conversation with the contractor so they can engage them to better achieve what they want from their designs. Technical knowledge can also help progress your design skills if you understand the technology used to fabricate things, you can incorporate that into your design work rather than coming up with a design that may be impossible or overly complicated to fabricate.

So what’s the most valuable take-away from your digital fabrication class, or other digital fabrication classes?

I’d want all students to understand that fabrication is a tool, and just like any other tool it can be as constraining or as liberating as they let it be. It’s up to them to think through it and figure out how it can be incorporated into their work. I definitely try to tell students that digital fabrication doesn’t necessitate design computation. You can be just as investigated in theoretical or contextual approaches to architecture and still be invested in digital fabrication, they’re not mutually exclusive. Just because you are into fabrication doesn’t mean you have to focus solely on computation and scripting. It’s up to you as an individual and a designer to provide the context through which you explore digital fabrication.

What does industrial machine and robotics have to do with architecture then? What does digital fabrication have to do with architecture?

I get this question quite frequently, either from family members or an architect who may not be comfortable with this type of work. I think it’s a valid question especially for incoming students who may not have any exposure to this stuff and are wondering what a robot has to do with architecture. I guess in response to that, these are old technologies. Numerical control was first developed here in Michigan, up in Traverse City in the late 40s and industrial robotics are equally old. These are all old technologies that have been around a long time. So what’s happening recently is that the price of technology has suddenly dropped tremendously - computers are affordable, everyone has one in their house. The same thing is happening with industrial manufacturing equipment, industrial robotics, and the like; all this technology is now more pervasive and now architecture schools are able to afford them. Modernism could be said to have evolved out of response to material possibilities that enabled a certain language of architecture – advancements in float glass etc. So similarly with these new technologies we can start to experiment with how they can influence how we make buildings. Some of the research that goes on in the FABLab with the robots is looking at how we can incorporate these technologies to make new things that would impact architecture. And even though we may not be able to scale up everything, we can speculate the near future possibilities with the technologies and ultimately, how it impacts the ways in which we make buildings. To me that is how this all relates to architecture: looking at ways to reinvent and reimagine construction and by incorporating new materials and new logics. I would say we are still in the early years of that, even with the progress that has been done by individuals such as Achim Menges and the Universität Stuttgart Institute for Computational Design (ICD) with their fully-enclosed robotically fabricated building.

So given that the range of faculty and students at Taubman are so diverse and may be disconnected from the FAblab, how do you see that manifesting itself for the faculty and the students?

I think the diversity allows for cross pollination of ideas. I’m still waiting for the day that Perry Kulper walks in the door and says, “Aaron, I want to do a robotics project.” My heart would skip a beat because I would love that. He would bring such a different inflection on what we are doing here and he would approach it in such a different manner. That’s what the FABLab contributes to the overall work that goes on at Taubman: everyone may be bringing their own agendas and design aesthetics or whatever it may be, but it is somehow being influenced by our approach of tooling and the culture of manufacturing and fabrication with robotics. And I don’t think it’s necessary that fabrication is the forefront of the conversation. It is for me because that’s my line of work and what I am interested in, but from an architectural standpoint, we don’t have to be talking exclusively about digital fabrication, but also about other ideas that we can use digital fabrication to explore. And I think the FABLab here at Michigan definitely supports a variety of work that doesn’t just talk about fabrication, but rather a range of ideas that leverage fabrication.

Sharing insights from Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.