The McHarg Center at the University of Pennsylvania has published a digital atlas that attempts to communicate the wide-ranging implications of both climate change and a potential Green New Deal for the United States.

The 2100 Project: An Atlas for the Green New Deal, as the project is officially known, brings together work conducted over the last two years by researchers at the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology, an initiative housed within the Weitzman School of Design at UPenn led by landscape architect and academic Billy Fleming. With the Atlas, the research center aims to answer perhaps the most pressing question of our time: "What will be lost—economically, culturally, psychologically, physically—should the climate crisis continue unabated?"

The answer, if it isn’t already obvious, is deceivingly simple: A lot.

By offering a look at four specific facets of the climate adaptation and decarbonization efforts that are either gaining steam or will need to be undertaken over the next few years, the atlas highlights not just what will be lost, however, but also, the vast and unwieldy nature of the project at hand.

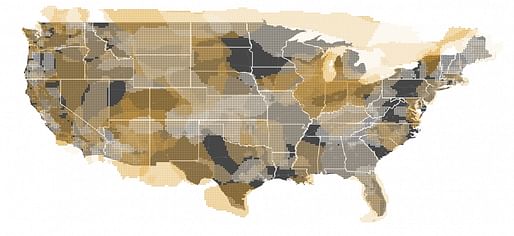

First, the Atlas uses a comprehensive set of national maps (encompassing the 48 contiguous states) to take an inventory of America's predominant land uses, highlighting the complicated interplay between dense urban areas (which take up 2% of America's landmass), sprawling "megaregions" (23%), agriculture (17%), and other land uses that will surely make the type of concerted, holistic, and fast-paced change necessary to achieve ambitious carbon reduction goals difficult to muster.

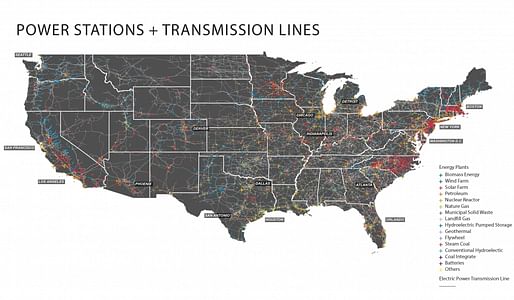

This section delves both into general land uses like those listed above, but also dives much deeper, measuring the scale and intensity of the country's major crops, water resources, meat production landscapes, and energy infrastructure paradigms. Again, the scale involved in simply accommodating this baseline projected growth will require a staggering degree of cooperation and development that can be hard to fathom under today’s dysfunctional and largely regressive urban design and regulatory approaches.

The Atlas, however, is constructed as a hopeful document. Describing the project, Fleming says, “The climate crisis is existential, replete with uncertainty, happening all around us, all the time. Though we have mapped it exhaustively here, maps alone cannot tell this story. We need more tools—for making sense of the climate crisis, for envisioning alternative futures that foreground what we might gain instead only what we’ll lose, and for stoking public imaginations and actions in ways that models, at least on their own, cannot. To paraphrase David Wallace-Wells’ apocalyptic book The Uninhabitable Earth, it is, we promise, better than you think. Or at least it can be.”

In addition to taking stock of existing conditions and uses, the Atlas also envisions what it would take to accommodate the projected 100 million additional people who are set to call America home over the next century.

The figure, based on United States Census estimates, is indexed relative to historic legislative efforts, racial demographics, and land development approaches across a series of maps that highlight the under-appreciated nature of the transformative period of growth that is on the horizon for the country.

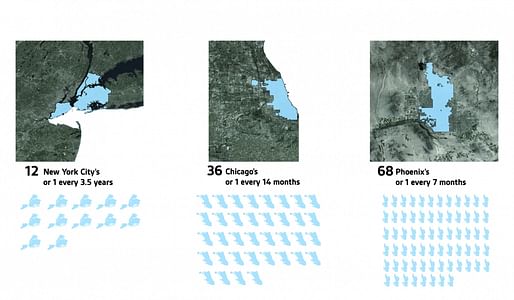

For example, America, according to the Atlas, will need to build roughly the totality of New York City 12 times over over the next 80 years in order to accommodate this growth. If distributed through low-density urban approaches like those that have shaped the American west and south over the last 70 years, the land-use issues become intensified and would require building the equivalent of 68 Phoenix-sized cities to house the same population, for example.

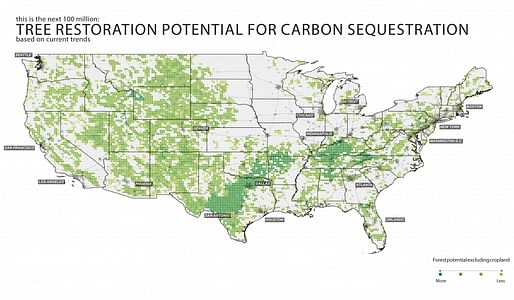

Lastly, the Atlas offers a roadmap for the future by literally mapping out how—and where—sustainable energy sources and other necessary services might be cultivated to fuel these populations, while also highlighting the massive amount of land that could be given over to reforestation efforts to sequester carbon that is already in the atmosphere.

In addition, the Atlas covers the economic, ecological, and climactic effects of climate change itself, offering a series of maps that log the amount of commercial losses that could take place due to climate change, for example, while also measuring and anticipating mass migrations that could result from extreme weather events like Hurricane Katrina, and cataloging the degree of sea level rise and displacement that could take place.

The scale of the problem—and, frankly, of the solutions—is daunting, to be sure. But it is a challenge that the researchers at The McHarg Center are embracing whole-heartedly. The center has emerged as perhaps the most visible pro-Green New Deal apparatus in the design field, a fact highlighted earlier this year when Fleming and others at McHarg joined forces with The Architecture Lobby and others to organize the Designing the Green New Deal symposium. In the months since, the center has contributed research to the recently unveiled Green New Deal for Public Housing Plan proposed by Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. These and other efforts are part of a larger push on the part of Fleming and others to reinvigorate the design community’s imagination with regards to how design and climate change coincide. As Fleming explained in a recent interview with CityLab, “There are some general things we’re certain about, but the shape and content of the future is not one of them. We get the future we build for ourselves.”

This work is worth a podcast. The range, the depth, the long term implications/advocacy...

All 1 Comments

This work is worth a podcast. The range, the depth, the long term implications/advocacy...

I second that. We can't get on this soon enough.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.