Following the Olympics’ closing ceremony, and as September’s Paralympic Games continue, international attention has begun to shift to the future of Rio de Janeiro’s Olympic sites. These buildings must be built to evolve to accommodate Paralympic and future athletes, and the success of this change will set the precedent for Rio’s regeneration in the long term.

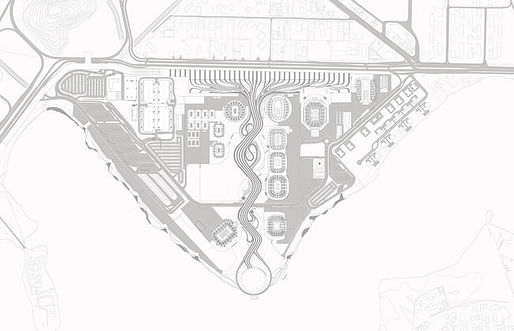

I spoke to Sam Wright of WilkinsonEyre, lead of their sports architecture team, about the firm’s Areanas Cariocas project: an incredible 400m long space for 3 venues and 36,000 spectators, making it the largest stadium at the Rio site. Having utilised his knowledge from the firm’s creation of London’s 2012 Olympic basketball arena, Wright spoke to me about the pressures and privileges of designing this colossal building, and to have, consequently, a huge involvement in the planning of Rio 2016 writ large and the city’s regeneration plan overall.

What have you learned from your involvement in the London 2012 Legacy that has informed your plans in this project?

Expectation. The design work for all Olympic Games follows on from an emotional, aspirational, exciting bid process. The documents laid out are ambitious and we have to weave a path that balances expectation with achievable results. All of the British design studios were emotionally charged by the commissions for London 2012 and our work in Rio 2016 definitely benefited from an understanding of the politics, the expectations and complexity of this procurement process.

We also understood the balance needed in dealing with the various sporting bodies who influence the designs; the Rio venue will be used by over 20 different federations all with their own requirements. We are experienced in managing the array of technical requirements and driving workable compromises. For instance, in London we were able to argue that the Basketball Arena did not need a ‘traditional’ centre scoreboard, taking a huge weight out of the roof structure.

What were the key themes leading the design?

Pragmatism, transformation, sustainability, and legibility. We knew when we were working on the Olympic Park Masterplan competition, and that the Mayor of Rio, Eduardo Paes, had been elected on a mandate of delivering practical and feasible solutions for the Games. The delivery of the Park was also going to be completely different to the London model; a consortium of two major contractors was going to be responsible for the delivery of the Park, retaining the majority of the site for their own development plans after the Games. Pragmatism was always a priority.

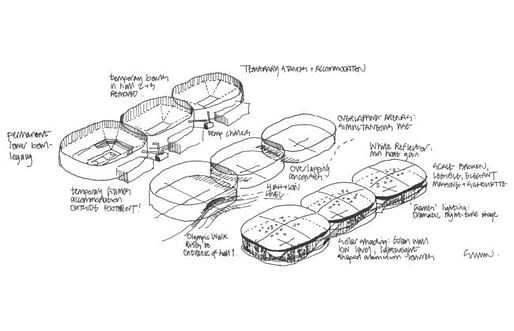

The focus of the AECOM/WilkinsonEyre competition designs was that of transformation, from Games to Legacy. This presented a fantastic opportunity to address the environmental issues in the Lagoon at Barra and to try to put in place a sustainable framework that was empowering yet achievable. The plans also had to be legible; the Games are a complex functional diagram—a world of segregated users, and ultimately the designs had to first serve this world famous celebration.

Leading up to the bid submission, what was the reaction to the design from outside parties? Have these changed?

As was the case in London, the reactions to the designs both post-competition and leading up to the Games have been somewhat overshadowed by social and economic issues; in Rio the big issue is how to improve public security. In the weeks leading up to the Games the focus had switched to environmental issues and concerns to the levels of air and water pollution. We remain optimistic that our team’s wider proposals to address the pollution levels in Jacarepagua Lagoon will bear fruition.

The design's approach to environmental issues has been celebrated; how did the design process incorporate this and what challenges arose?

Our aim was to deliver a remarkable venue, building on our expertise from London 2012 to “conserve, re-use and recycle” and also conveying the spirit of this approach. We put great effort into ensuring the language of the architecture and the visual finish conveyed this message, for the global audience watching the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games and for the legacy of the Elite Training Centre.

Our principal approach to a sustainable design was to ensure the transformation works were kept to a bare minimum, and that the legacy use and operation of the building informed the Games mode, not vice versa. All overlay spaces, including the mechanical and electrical plant—which is only required for the month-long Games period—have been approached as a ‘plug in’ design and will be simply removed afterwards.

Our second approach was a passive design of the building envelope and a space cooling system. The roof is vast—400 meters long by 100m wide. The most efficient and simplest design was to adopt a white, reflective lightweight solution, which is punctured by an array of sun pipes to gain as much natural daylight as possible.

The cooling strategy is relatively simple. We deliberately designed out any rooftop or high level plant; in Games mode the space under the seating bowls acts as a cold air plenum, pumped up from temporary air handling units located at ground floor. In legacy mode an array of big, walk-in ducts will draw in cooler air from the outside, dried through a desiccant, and rolled out at low velocity at the edges of the sports floor. Exhaust air is drawn through collars around the sun pipes and through pressure relief dampers at high level.

Following your focus on legacy in the Arenas Cariocas design, what are your hopes for Brazil as a whole following the Games?

Sport has a unique way of binding populations and communities together. We all felt a huge uplift in pride and belief after London 2012. We can only hope that the media spotlight on Brazil will engender an inner belief for the people of Rio and put political pressure on local government to address the endemic problems of security, human rights and pollution. Regeneration is long overdue in Rio; it is a sprawling and beautiful city.

This summer, the spirit of sport and of regeneration for Rio has certainly lifted hearts and inspired people around the world, which will carry through to the Paralympics in September. Next time we see the Areanas Cariocas it will be the venue for wheelchair rugby, basketball and boccia. The adaptable design allows for flexibility; for years to come it will be a leading training facility and setting for future sporting events.

As for Tokyo 2020, we look forward to seeing Kengo Kuma’s design for the national stadium come to fruition after its turbulent beginnings, and seeing whether the venues can compare to the flexibility and consideration seen in Areanas Cariocas.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.