If architecture is the ultimate fourth dimensional experience, then “Architectural Guide China” by Evan Chakroff, Addison Godel and Jacqueline Gargus is a remarkable fourth dimensional tour guide. It encapsulates not only the physical attributes and detailed locations of architecture in China, but its complex journey through time in a way that's compact enough to be useful, yet thorough enough to be thought-provoking.

The guide begins with three introductory essays, each of which attempts to make sense of the thousands of years of history, philosophy, and socio-economic realities that have informed both classical and contemporary Chinese architecture (all in less than fifty pages). This is of course a daunting if not impossible task, but each essay wisely chooses a specific aspect of this overwhelming scope to make a particular point. For his part, Evan Chakroff chooses to tackle what he describes as the centuries-old notion of ‘scalelessness’ in conjunction with rigidly defined diagrams of urban spatial layouts. In essence, the basic layout of a dwelling may have been prescribed, but the size of that layout was often changed to create different meandering narratives or feelings of belonging among those who encountered the structures.

“In dynastic China’s urban planning, the scale of the city is defined as a continuum associated with the dominant social hierarchy,” Chakroff explains, before leaping into the aesthetic disruption of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when foreign influence began to muck up the traditional spatial ordering of cities to make way for cars and commercialism. To make this point, he contrasts Beijing’s more traditional “nested, recursive geometry” with Shanghai’s relatively more modern but simultaneously fragmented urbanism. He then uses this historical grounding to analyze the relative architectural success of various 21st century structures such as OMA’s CCTV headquarters, simultaneously (and quite helpfully) referencing the page number in the guide where the specific structure can be viewed in real-life.

Meanwhile, Jacqueline Gargus’ essay delves into traditional Chinese aesthetics, and the long history of China’s intertwining of mediums: she examines gardens, specifically the Humble Administrator’s Garden, whose 48 pavilions were designed to enable sophisticated appreciation of both nature and culture. She quotes a 17th century epigram to illustrate this relationship between aesthetics and literature: “The sounds of pine trees, of brooks, of mountain beasts, of nocturnal insects, of cranes, of lutes, of chess pieces falling, of rain dripping on steps, of snow splashing on windows and of tea boiling are all sounds of the utmost purity. But the sound of someone reading is supreme.” She closes the essay by explaining how this tradition of intertwined aesthetic relationships is one of the greatest challenges young architects working in China must combat: weaving the seemingly disjointed threads of globalization into this longstanding, complimentary marriage of arts.

Finally, Addison Godel rounds out the essays sections with an examination of just what ‘modernity’ means in a century that has as many new starting points as it does dead ends. “It’s clear that the generation which came of age in the 1980s and 1990s has its own priorities and is willing to explore the ambiguities and conflicts of being Chinese in the age of globalization,” she writes of the designers currently working in China. With the profession of architecture itself in something of a swivet about the effects of celebrity and globalization, Godel convincingly argues that the design future of China is inherently linked to not only one’s perception of history, but of one’s relative understanding of what architecture itself can do or should be. This is as much to do with the evolving reality of a globalized urbanity as it is the sometimes overbearing notion of “history.” As a U.S. native growing up in the South, Godel explains this disjunction between one’s perceived historical roots and actual lived experience via the example of her feelings on seeing plantation-era architecture versus elements of the modern age. “A designer hoping to poetically reach my deepest feelings of rootedness and harmony would do better to exploit crinkled plastic photo albums, VHS cassettes, and wood panelling. Indeed, some of the most interesting work in China is concerned with the immediate past, and the spatial legacies of the twentieth century.”

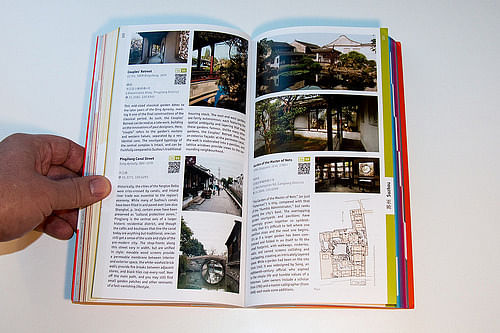

Part of the charm of the guide is that it makes no claims on being able to survey absolutely every building of note, or even every style; indeed, its primary focus is on contemporary work, with an occasional spotlight on “‘must-see’ masterpieces from China’s very long design history.” The guide divides itself into eleven principal, color-coded sections, each of which focuses on a particular city, starting in the northeast with Beijing and gradually meandering down the coast to the southern port city of Macau. A selection of structures from a few inland locales, including Chengdu and Pingyao, are fleetingly profiled in the “reference” section. Mimicking the historical scope and fourth-dimensional nature of the essays, each city sections gives a historical overview of the history and architectural legacy of the particular city it is surveying before showcasing individual structures. Detailed maps arrange the profiled sites in a way that would be most helpful to a visitor unfamiliar with the city who wishes to make the most of his or her time, and each site comes with its own (soon to be outdated?) QR code for on-the-go smartphone mapping.

“Macau (or Macao) is sometimes described as the ‘Las Vegas of Asia,’ but it might be more apt to call Las Vegas the Macau of the United States,” begins the introductory text for the Macau section, before going on to detail its Portuguese influence and boom-and-bust economic cycles. Shenzen, meanwhile, is fascinating for its incredible short-term growth, a place in which “almost none of its present-day fabric is older than the 1980s.” This sections functions as a guide not only of visually compelling places such as the Cultural Centre and the Shenzen Stock Exchange, but the very development of contemporary 21st century urbanity.

Regardless of what city or sites one chooses to visit, the guide distinguishes itself by continually referencing not only the actual structures, but how their global architectural lineage and complex history shapes them. To use this guide is therefore to be a tourist not just of physical places but of history, modernity, and the ever vacillating notions of what noteworthy architecture is.

2 Comments

Thanks for the great review!

Note that the book is now (finally!) available for order on Amazon.com:

http://www.amazon.com/China-Architectural-Guide-Evan-Chakroff/dp/3869223480

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.