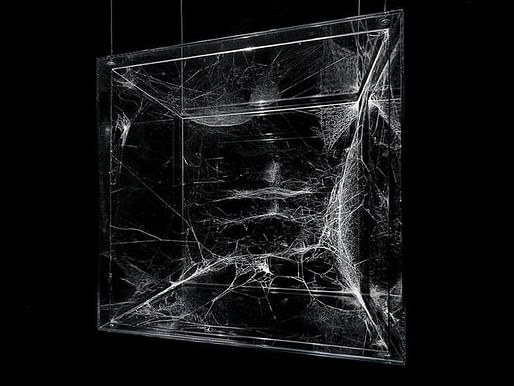

For the first few seconds you’re blind in the darkness. Then a reflex forces your pupils wider and your photoreceptor rod cells become more sensitive, sending a neural signal that alerts you to four glowing cubes that seem to be floating in mid-air in front of your body. It takes another few seconds for the glow to connect to its source, illuminate the supports of the plexiglass boxes, and finally render their content legible: a series of startlingly-complex and impossibly-delicate spiderwebs.

Here drawing back the curtain doesn’t destroy the magic. Quite to the contrary, Tomás Saraceno’s collaboration with various arachnids for the first Chicago Architecture Biennial has a power that extends beyond some mere trick of the light and runs deeper than a one-liner about non-human construction. It's a reprise of a project he's exhibited before, notably at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, but within an architectural context it conjures a particular significance.

The Argentine-born, Berlin-based Saraceno is known for an art practice that draws from diverse fields including physics, chemistry, aeronautics, engineering, and, yes, arachnology. Trained as an architect, Saraceno often makes inhabitable structures such as his “Cloud Cities” of giant inflated orbs or 14 Billion (Working Title), a blown-up model of a Black Widow spider web.

For his installation for the Biennial, each of the boxed-in webs is accompanied by a title that elucidates details of its production, like the specific genus and species of spiders and the duration of the construction. According to a text in the exhibit catalogue, Saraceno rotated the boxes as the spiders wove their webs, forcing formal changes.

Like with any good collaboration, authorship is played with rather than rejected forthright. The spiders are the ones making the construction, but Saraceno has god-like control over the world in which they work. Conversely, while Saraceno might manipulate the conditions of the worksite, the spiders retain a fundamental agency over the aesthetic of the structure that emerges from glands in their abdomens. As the catalogue states, “The intricate web formations in each cube neither belong to human logic nor are something that would exist in nature.”

It’s not the first time that spiders have been pointed to as likely the most talented architects in biology (perhaps including humans), and beyond the charm of its presentation, the efficacy of the installation depends to a large degree on your reading. In the vein of biomimetics, you can interpret the forms as inspiration for the (implicitly more important) work of humans. Alternatively, you can take the project seriously as a collaboration between human and non-human architects.

Certainly, one would not be totally remiss if they chose to read this installation representationally, particularly since the vast majority of its neighbors in the Biennial demand this approach. And there’s not exactly a shortage of lessons to be drawn from the application of such logic – about form and structure, but even more about the hollowness of architectural pretensions of autonomy and authorship under conditions that are fundamentally uncontrollable.

These readings, which assume as inherent a human as sole or at least central subject, are exactly that: readings, which is to say, interpretations of objects as signs, translations of wonderful structures into legible lessons. No doubt, there’s merit to this. But Saraceno’s installation also does something different, something unique at the Biennial and more broadly in architecture.

From when you pass into the dark of the room, to when you’re blinded again as you pull back the curtain and exit, the installation structures an experience of estrangement and defamiliarization that fluidly extends from the architecture of the space to that of your body. Involuntarily, your eyes adjust to the change in light so that you are capable of perceiving the mesmerizing architecture in front of you, in turn produced by some likely-unconscious imperative inherent in spiders.

As you leave and your eyes again perform their hidden machinations, the rest of the Biennale – from the ornate Beaux-Arts architecture of the Chicago Cultural Center to the installations that mainly try to elaborate some principled or logical or conscientious imperative for how a bunch of apes ought to build their dwellings – takes on the strange hue of the alien or the animal.

Saraceno’s installation neither delivers a lesson about what architecture is today nor prescribes what architecture should be tomorrow – it does something much more noteworthy.

3 Comments

That last picture... Spiderwebs!

Wake me up when the Pomo nostalgia ends

A lot of these exhibits seem clever but missing something .... Whereas Gaudi used natural devices, he had the drawings and work attached. Instead you need a long exposition here to make sense of it. Art with no architecture..... I'd have a hard time taking anyone who wasn't a 20-30 year old art major

awesome idea

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.