While most attention falls on the national pavilions at the Venice Biennale, the city itself hosts an uncertain number of simultaneous, satellite events, operating somewhat under the public's radar but still orbiting around the Biennale's curatorial center. There are the Biennale-recognized roster of exhibitions, called "Collateral Events", and then there are the outer planets of the Biennale's solar system; the unsolicited riffs taking place at smaller, less conventional spaces throughout the city. The Biennale's five-month run gives ample time for dissent and complication within the city, offering alternate interpretations to this year's sanctioned theme: "Fundamentals", from Rem Koolhaas.

Criticism of Koolhaas' biennale has been well-trodden. Creating a catalogue of architecture's supposedly "fundamental" elements has been called depressing, inappropriate, cynical, or pejoratively part of Koolhaas' cult of personality. Reporters griping and academics critiquing is a fundamental part of any gigantic institutional event, but rarely do direct, constructive ideas materialize from those gripes. The Biennale should be provocative, and unaffiliated, unsolicited peripheral events can be perfect vehicles for this purpose — a prime example being Columbia University's "House Housing: An Untimely History of Architecture and Real Estate in Nineteen Episodes".

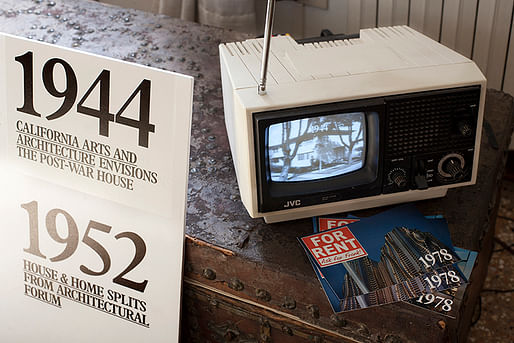

Disguised as an open house in a Columbia-owned Venetian apartment, "House Housing" is a mash-up of domestic set-pieces, from different eras of American housing history — like a benign Frankenstein's monster of living rooms. Visitors to the apartment passed through homey spaces, scored by the transmission of "episodes" from the last century, broadcasting primary sources through native media devices, from phonograph to iPad. These include snippets from news pieces about the subprime mortgage crisis, Trayvon Martin's shooting in a Florida gated community, the rise of Dwell magazine, and the new company towns of the 1970s, among many others. The fundamental that unifies these episodes, missing from Koolhaas' list of indispensable 15, is economics. Housing architecture in the US is a synecdoche of the nation's economic fluctuations. The real estate market's rhythms determine and influence Koolhaas' "fundamentals", and it's naive to presume these supposedly inalienable elements are unaffected by the economy that, literally, houses it.

The exhibition was organized by Columbia's Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture, whose director, Reinhold Martin, had previously criticized Koolhaas' biennale' for this fundamental omission. In a piece for Design Observer, Martin explains how the concept of "land" (or in practical terms, "real estate") determines our definitions of space and dominion, and therefore, of architecture. He finds it demeaning to reduce architecture to "a timeless set of logical subsets", and that reverberates throughout House Housing. The actual apartment interior appears very casual — not too neat, not too messy, not to hip, not too traditional. As best as I could tell, as a virtual observer, the apartment's mood doesn't really change from room to room, but the broadcasted media does, and drastically, switching from a televised Obama speech to a crinkly radio report to a robotic answering machine monologue. What seems fundamental is subject to change with the time's economy, as does the media, and housing is at the incendiary focal point.

"House Housing" was open for a mere eleven days in June, but the exhibition can still be glimpsed through a short trailer on its website (also see below), and an explanatory list of all the news items referenced. Koolhaas' biennale chose to ignore architects in deference to a typological purism; that what defines architecture is its structural elements, taxonomically organized, and not its designers. The missing keystone is that these structural elements have to land somewhere beyond the drawing board or museum space to be called architecture —those fundamentals become reality when placed on land, trading negative space for architecture, at a cost. To omit economics is to go back to virtual reality. And money talks much louder than toilets.

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

No Comments

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.