I grew up in a masculine household; my dad was a crane driver, and he operated those wrecking ball cranes that would slam into buildings to demolish them (obviously without Miley Cyrus sitting on the steel sphere). I was going to say a bit like the game conkers, but that wasn’t a thing here in the USA; google it.

He was also involved in ‘chimney felling,’ where a tall chimney is demolished, through either fire or explosives and it crumbles down.

During the 50s and 60s, at the peak of my dad’s career, the zeitgeist in the UK and more so here in the USA, was to knock down the old stuff and start afresh. To create a ‘tabula rasa’ as opposed to try and improve on the three-dimensional ‘palimpsest’ which would often prove complicated and expensive, although could actually end up looking quite beautiful. Think of Rafael Moneo’s National Museum of Roman Art in Merida, Spain, where the old and the new intertwine beautifully.

Many examples of Brutalist architecture which emanated from the policy of ‘all things new’ were fantastic. Think of Walter Netsch’s Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago built in 1967, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple built in 1908, and Sir Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre in London. Wonderfully designed, although better suited to sunnier continental climates, extenuating the play between light and shade and dramatically dark shadows. You don’t get that on a grey day in London.

All this demolition eventually resulted in my father setting up his own demolition business in the late 70s. I was born in 1974, and I remember vividly the sense of joy my dad had when he came home from work – like a big teenager being allowed to smash things up, get paid for it AND get to keep all the redundant materials. Things like copper wiring, lead roofing, unique terracotta tiles, church bench pews, you name it, he could sell it on. This was before sustainability and re-use was a ‘thing.’ “There’s money where there’s muck!” my dad would say, proudly echoing the old Yorkshire saying.

At the time, I secretly wanted him to be an accountant with a 9-5 job and drive a Ford Contour. He would come home from work covered in oil, diesel, dirt, and whatever else would be found on a demolition site and hug me and my brother. I would squirm, but my brother loved all the muck!

I’m writing this because it gives you, the reader, some context into my childhood. My dad would let my brother and I sit on his lap sometimes and control the levers of the JCB and move the digger arms to dig holes or whatever. My brother LOVED it. I was mildly interested; I just remember worrying how dirty I was getting and how I didn’t like the smell of diesel/oil/WD40 - I love it now my dad’s gone, as it reminds me of him since he passed.

“You’re always reading,” my mum would say, “You should get out more like your brother!” I think mums today might be happy to see their sons reading rather than getting muddy. Perhaps I was born in the wrong generation.

I’m not sure if it’s the same now, but in the UK in the 80s, you were encouraged to start thinking about what you want to do for the rest of your life at an early age. This is something I think the United States have a really progressive grasp on; choosing electives, minors and majors – it’s like a smorgasbord of education, so there’s not too much pressure to make a career decision until you’ve tried out many things. In the UK you choose specific GCSEs at 14 and then even more specific A-Levels at 16.

This is something I think the United States have a really progressive grasp on; choosing electives, minors and majors – it’s like a smorgasbord of education, so there’s not too much pressure to make a career decision until you’ve tried out many things

Initially, I wanted to get into fashion as a career; my mum was super glamorous and I’d sit and watch her put her make-up on and get dressed up for hours, ‘The Transformation’ she’d call it. Fashion Design in the 80s, especially for a boy from Wales, didn’t seem like a proper career. Wales wasn’t a beacon of progressive attitudes back then and I think I was smart enough to realize that that would confirm everyone’s suspicion that I was gay; wanting to study fashion. ‘Coming Out’ cards weren’t a thing back then.

Architecture seemed like a good compromise. I’d been on loads of building sites, seen buildings knocked down – why not build them up? I was good at art and I LOVED Lego. It was architecture, the mother of all art. To this day some of my friends call it Urban Hairdressing. #rude.

This was the context for my decision to become an architect at 14 years old. I precociously wrote to the RIBA and got information about what to do, how long it takes, what schools are good, what should my A-Levels be, how much one could earn. I remember thinking that a £12K starting salary was a fortune. I came to believe that Architecture was my DESTINY. It’s actually quite wonderful when you’re 14 and you are 100% certain of what you want to do with the rest of your life.

Architecture also sounded ‘cool.’ We all remember how important cool was when we were 14. “I’m going to be an architect!” “Wanna hang with us?” Yes!

I’m going to be an architect!” “Wanna hang with us?” Yes!

After that decision was made it was study, study, and more study. You weren’t encouraged to mix arts and science at my school back then so I did mathematics, physics, and chemistry at A-Level. I found English, French, and art easy so what was the point in that? I wanted to improve on my weaknesses!

My parents bought me a car at 17, and although still living at home, I felt very grown-up. After my nosey mother discovered my homosexual deviancy by reading my diary (I’d only written about a wet dream, I wasn’t doing anything exciting) everything was out in the open. No more secrets and I could focus on more study and eventually succeeding in becoming a famous architect.

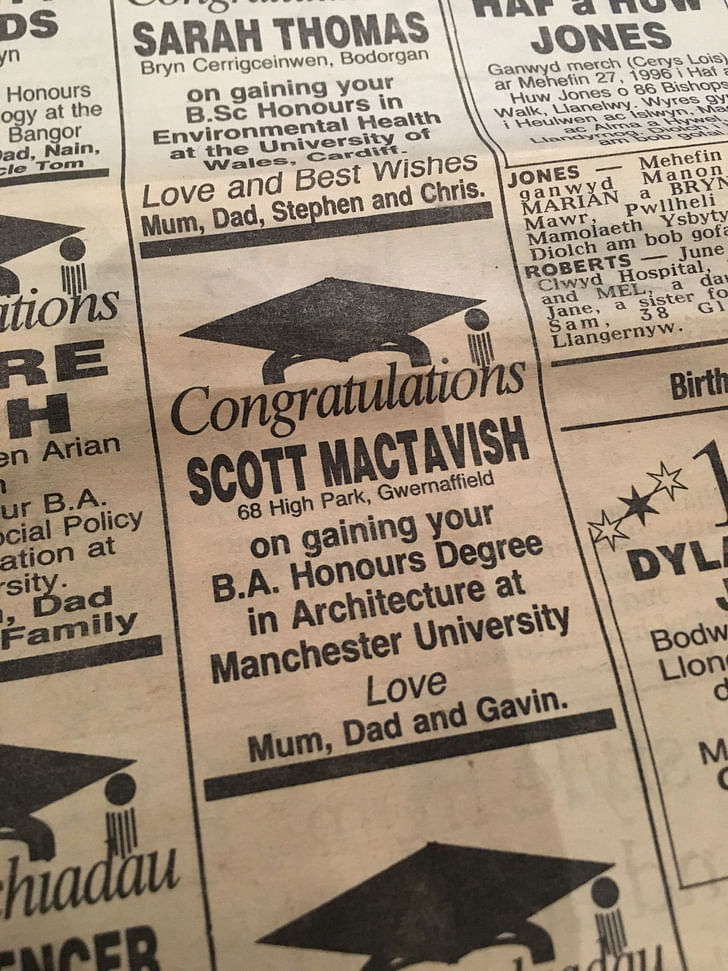

When my exam results came out in 1993, I’d won a place at my first choice of college, Manchester University, which I was ecstatic about. Academia aside, the city was also burgeoning musically, culturally, and gaily (Did anyone see Queer as Folk? That was basically my life, but with a lot of architectural study thrown in).

I studied so hard! I loved it; making loads of models out of crappy cardboard, going to the studio at all hours to create and see what everyone else was doing. Being weirdly secretive and protective about my work but at the same time wanting to share and sort of help others (but not too much). All working towards the infamous ‘crit.’ ‘Big reveal’ might seem a better term today in the dumbed-down cultural media jungle we find ourselves in.

Diversity wasn’t big on the agenda back then. From memory, I would say roughly 60% had been educated from a private school and 30% of the whole class were female. There wasn’t one black person in my year, although I did meet a British Asian Muslim who remains one of my closest friends to this day; it’s never quite the same if I go to an art gallery without her, even now after 30 years. And there was just me and another gay guy on the course. He was a way better artist than me; truly inspirational.

So here I was, studying at the same school as Sir Norman Foster, living a fabulous student life in this amazing city, surrounded by smart, like-minded people. The happiest days of my life thus far (it does get a bit crappy with the 9-5 job, the mortgage, and hard to manage moobs when you leave student life, don’t you think?)

I could go on endlessly about how much I loved studying architecture; the finger painting in the first year, the field trips to far off places, critiquing a piece of toast on a wall (admittedly that was in my Master’s degree) smart, funny, cool people from all parts of the world. The creativity and the encouragement to think ‘outside the box’ and to look for many different solutions to presented problems, what was not to like?

I do remember in my first semester raising the question of fire safety in a building that was being ‘critiqued.’ I distinctively remember the collective ‘eye-roll’ from the tutors and some of the students. “Plenty of time to worry about that later” came the response. I mention that now as it seems poignant and ironic in light of the UK Grenfell Tower disaster in 2017 and even the recent Miami Building collapse – the practical questions got pushed to the back; it was always about the ‘art.’

Manchester University represents one of the best architecture schools in the world (currently at No.11 out of 220 from QS University World Ranking 2021). Is it poignant and ironic? Or just tragic that fire safety is of no concern in architectural education? Or at least it wasn’t when I was being taught it. Hopefully, it’s being addressed more now.

Is it poignant and ironic? Or just tragic that fire safety is of no concern in architectural education?

Critiques obviously stem from the verb ‘to criticize’ – I’ve always thought it was best to talk about the good bits first in a design and then constructively criticize the shit bits afterwards. A lot of the time, tutors and design directors just want to blast you – maybe it makes them feel better. Male egos and all that. I do hope that more architecture schools nowadays try and encourage the work of their students. It would be interesting to hear in the comments how critiques are performed nowadays. Many a time a devastated student would shuffle off holding back tears, me included!

Although I worked incredibly hard, design never came naturally to me, it was more of a struggle. Many of my peers would grab a fat pen and just start sketching away and produce an amazing visual representation of whatever was in their minds. Or throw a cardboard model together quickly, easily, and beautifully – successfully representing ‘the vision’ and looking like Henry Moore had been undertaking a bit of design development.

I was much more angsty and rigid; worried before I’d even begun. I always wanted a final design and idea in my head before I started sketching anything. Perhaps I was craving the Lego plan to guide me? Early on, one of my tutors said that I needed to explore different options and not settle on the first one that came into my head. I completely agree now and see what he meant. I still do it today; settle on one idea and just try and get it done quickly. Almost like rushing through life; get it done and out of the way as soon as possible.

From then on, I took his advice and started to explore more options – I think it helped a bit but then it does make the whole process harder when you’re looking at all the parameters and options in architecture – there can be so many solutions to one problem. How arrogant to think that the one you choose is the right one. Maybe that’s why I wasn’t as good at design as I’d hoped I would be, I was not arrogant enough.

Maybe that’s why I wasn’t as good at design as I’d hoped I would be, I was not arrogant enough

The tutoring paid off (I guess that’s why they’re there after all) and in my second year, I had an amazing and inspirational tutor who was totally awesome. He’d always ‘big-up’ your good ideas and suggest even better ones to compliment the original direction, so it was still ‘your’ design, so to speak. He gave me the confidence to eventually design competently and I ended up with a good first degree and happily won a place at The Bartlett, UCL, for the second part of the architecture adventure, my Master’s.

In the USA, the shortest time it takes to become an architect is 8 years (although the average length to actually qualify is 12.5 years!). In the UK, the shortest time is 7 years – 5 years of study and two years in training at an architectural practice. The two years I had at the Bartlett were amazing – the people there really were the best of the best! I remember my first day sitting in a hall with all the new students assembled and Peter Cook grandly announced that for every person seated, there had been 20 applicants.

The Bartlett was a weird and wonderful place. The Unit I chose to study in was heavily computer and CGI-focused and the tutor was smart, funny, cool, and clever. He taught me how to post-rationalize my work which meant you could literally do anything you wanted and then afterward make up a convincing reason why it was like it was. That felt a bit wrong and inauthentic but as long as the end result looked good it definitely worked.

One of my projects was a sex library where anyone could go and watch porn, masturbate, and connect with like-minded people globally. Like a seedy Times Square in the 90s but a ‘media-tech’ edifice to legally house the sexual shenanigans; a bit like Scruff, Grinder, Tinder, or whatever now but with a physical space.

Anything political and/or shocking seemed to go down well at the Bartlett. There was a joke going around at the time when someone said, “Oh wow, you’re doing an actual building!” I wonder if it’s still like that?

Anything political and/or shocking seemed to go down well at the Bartlett. There was a joke going around at the time when someone said, “Oh wow, you’re doing an actual building!”

My final project was based on William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer; it was a celebration of digital mistakes and 3D objects I’d found lying around in the school’s electronic wasteland. A kind of digital Le Palais Ideal in Hauterives, France by Ferdinand Cheval, where random bits of digital detritus were collected to make a whole, only this time in cyberspace. The result was beautifully rendered images and animations, funky music, and not a brick in sight. The late Per Kartvedt, who was the external examiner on the project, struggled with the concept, “He’s very superficial” he said to my tutor after the viva voce. “You mean the work is?” I countered. “No, he thinks you are.” grinned my tutor. I do remember thinking I could charm my way to a distinction. I never got one. I found out I was really good at sales later on though.

I do remember thinking I could charm my way to a distinction. I never got one. I found out I was really good at sales later on though

Many of the people in my unit ended up directing pop videos for Bjork and becoming successful music directors in their own right. Some even married famous pop stars. I waited and waited for my famous pop star to come along, but he didn’t. After graduation, I needed to get a job quickly and start paying off those student loans.

Don't miss part 2, "Surely there are easier ways to make money?"

Scott studied his Masters in Architecture at the Bartlett School of Architecture and his BA Architecture degree at Manchester University. His professional industry experience spans education, commercial and residential sectors, gained at award winning design practices including CRTKL, Austin Smith ...

6 Comments

What a great article and I learned a bunch of stuff about my best friend here in NYC. Especially interested to ask you about the sex library when I see you next ;-). Keep writing, Scott !

this was such an interesting good read! I highly recommend :)

What a beautifully crafted memoir of a young welsh boy who followed his passion. It is inspiring to read and I fail to see how you could not achieve a "distinction". I'd consider applying post eventum with this article alone! Its a brilliant recant and one can only hope there is a novella on the horizon. Please keep writing I will follow with interest...

You're cute and hot. I'm just about to start my postgrads MArch at Bartlett, (and directing music videos for Bjork is like my dream (just like Andrew Thomas Huang (but also that dream comes after making whatever garment for Gaga))). Haven't read the second part. But being superficial and shallow is a blessing, a divine intervention that suppresses the pain. It's like creating your own language that is not supposed to be understood by others, and those US universities certainly won't understand

Thanks for sharing Scott!

"I had an amazing and inspirational tutor who was totally awesome. He’d always ‘big-up’ your good ideas and suggest even better ones to compliment the original direction, so it was still ‘your’ design, so to speak. He gave me the confidence to eventually design competently and I ended up with a good first degree and happily won a place at The Bartlett, UCL, for the second part of the architecture adventure, my Master’s."

Those are the good instructors.

Great article!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.