Sometimes, when we spend so many years pursuing something, striving for a far off goal, and then reach it, we can become dissatisfied, or even depressed. "Is this what I've been working toward? Will this be my whole life now?" we might think to ourselves. It's a common thing for many graduates: you go into a firm, and the shock of professional life begins to diminish the zeal you once had for architecture. Even after gaining years of experience, we reflect on how far we've come and begin to yearn for something more. "Do I still want to do this? Is this job leaving me fulfilled? Has it just become routine?" These are all legitimate questions, ones we may all ask at some point. And whether it's as a recent graduate or an experienced professional, the issue of questioning our passion for architecture is something worth addressing.

“I want to know what passion is. I want to feel something strongly.”

- Aldous Huxley

A couple of years ago, when I was contemplating my own place in architecture, I had done what many do when they start to get tired of professional work: I considered getting a Masters Degree. My alma mater had recently created a Masters of Science in Architecture program, and I was interested in it. One day, during my lunch break at work, I had a phone call with one of my professors about some of my thoughts, and he shared his early career experience with me. "When I graduated and started working at a firm I couldn't help but feel like I was wasting my time," he told me. He wasn't enjoying architecture during that time of his life, his passion was dwindling. It turned out he wasn't wired for firm work, he had more of a mind for academia, research, and teaching. He ended up leaving traditional practice and pursued higher degrees in architecture and now has a fruitful and fulfilling career as a professional academic. His issue wasn't with architecture, but rather what he was doing within architecture.

Around that same time, a good colleague of mine was beginning to feel unfulfilled with his job and even considered leaving architecture. "I don't know, maybe I can try construction management, or maybe I can go back to school for something," he said. It was weird hearing this from him, because almost two weeks prior to this conversation, he was so enthusiastic about his future as an architect. What happened? We talked again a couple of months later, and he said that he was rethinking his plans to pursue an alternative path. "I really want to take on bigger responsibilities, I'm ready to be a job-captain," he said.

He had gotten bored with his day to day work, he was ready to take his skills to the next level. He had been working professionally for about three years at this point and had a fantastic mentor developing and teaching him throughout that time. He was more than ready to take on this new role. Fast forward a couple of months, and he had become a junior job-captain at that firm. He expressed his desire for more responsibility to the leadership and was able to take a step forward. Today, he's working at a new office in an even higher position of leadership. Architecture wasn't the issue, it was that he wasn't growing and became tired of the stagnation.

“The purpose of life is to live it, to taste experience to the utmost, to reach out eagerly and without fear for newer and richer experience.”

- Eleanor Roosevelt

Julia Gamolina grew up with a wide array of interests and curiosities. Even as early as first grade, she participated in after-school activities ranging everywhere from language learning, to dance, to vocal and theatre classes, and arts workshops. Almost every hour of every day was filled with stimulating activity that engaged her mind, her body, and satisfied the enthusiasm she had for learning. As Julia grew older and prepared for college, she decided to pursue architecture. "I chose to study architecture because it was so multi-faceted," she shared with me. She loved the historical, analytical, and theoretical aspects of architecture as well as the hands-on and presentation characteristics experienced in studio work. In short, this field of study embodied what Julia always had a passion for—exploring a lot of different skills and dynamically exercising her mind.

But, when Julia graduated from school and started working in a firm, she found that she was only engaging a small part of her mind. "When I started working, I realized that the bulk of my time would be dedicated to one sliver of the profession — mostly drafting and some design," she said. For her entire life, she had been able to satisfy her diverse interests, but now, as a professional, she felt suppressed and soon began to explore ways to fulfill her appetite for greater engagement. "I started to look for ways I could expand my contribution within the firm I was working for and also for things that were stimulating outside of work. I knew I liked to draw, write, and meet new people, so I started to do as much of that as I could," she reminisced.

Soon the young professional got involved in the communications and business Development endeavors within her workplace. She began to review internship applications and interview candidates for the firm leadership and quickly discovered that she loved meeting and learning about new people; this also expanded into meetings with clients and consultants. Julia also began to solidify her love for writing and began to write for ArchiteXX, a non-profit organization that focuses on gender equity in architecture. She asked the organization if she could interview one of her mentors for their blog. And, over two years, one interview soon turned into four, and eventually evolved into Madame Architect, which Julia launched in May 2018. Madamearchitect.org is an editorial platform "about women putting their narrative and their story at the forefront, about giving them a voice and a platform." The website now has over 80 published interviews about 80 different women, each with a unique and captivating story.

Working with people and writing are now the core of what Julia does each day. In addition to Madame Architect, she also works in business development at FXCollaborative. Julia is also on the ULI Young Leaders Group Committee, is a founding member of the co-working space and social club The Wing, and writes a monthly column for A Women's Thing.

“Your art is what you do when no one can tell you exactly how to do it. Your art is the act of taking personal responsibility, challenging the status quo, and changing people.”

- Seth Godin

Sometimes it can be scary to make a shift and veer off the beaten path. Julia Gamolina had committed to an entire undergraduate education in architecture, and after working professionally, realized that the traditional route was not for her. She had identified what she loved at an early age and saw architecture as a way to fulfill that passion. She saw that many of her colleagues enjoyed the day to day work within a firm, but realized that she did not share their enthusiasm. Did this make her "bad" or "wrong" in some way? Did she waste her time with school and study only to throw it all away at the end? Not at all! Often we can start to feel trapped in a path, we might think that it's too late for us to switch gears, that we've devoted too much time to a particular goal and that we have to see it through even if we don't find any fulfillment in it.

We can stay and wallow in our discontentment, or we can learn from Julia and take steps to rediscover what it is we love about the path we've chosen. Like my professor, Julia always loved architecture but needed to home in on what she was meant to do within architecture. For her, that was writing and talking to interesting people. She took an active approach to find her place in architecture, and even though it took a couple of years of trial and error, today, she's captured those inherent qualities she always knew she enjoyed most.

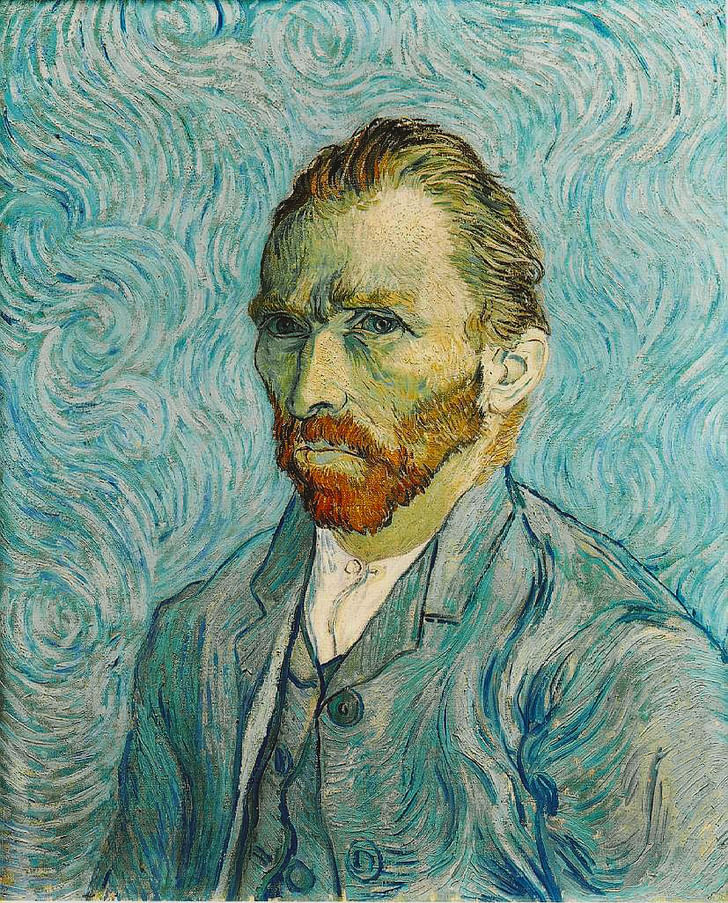

“The beginning is perhaps more difficult than anything else, but keep heart, it will turn out all right.”

- Vincent van Gogh

For Michael Riscica, architecture school was the first time that he excelled academically. He fell in love with the studio experience, of designing elaborate fictional works of architecture, with learning the theory of architecture. "I wanted nothing more than to live in this imaginary world forever," he shared with me. But, when Michael graduated from school, he struggled for the first two years. He had difficulty coming to terms with what he was doing as an entry-level professional. "I felt like I was just pushing paper, sitting in a cubicle, and felt seriously disconnected from what had happened in architecture school," he remembered. He no longer experienced the creative freedom he had as an architecture student and felt like he had wasted his time in school. Something deeper was missing for him.

Then one day, he realized that his design education was still valuable. "I don't know if I hit my head or something, but I just finally understood that my time in architecture school was not a waste of time, it was just phase one of my development. The next phases were going to be about learning the practice of architecture: the business, how to execute projects, becoming a project manager, and having responsibility," he explained. Michael discovered a new part of architecture, he saw that school only gave him a small taste of a much broader field of study. After coming to this realization, Michael began to take his Architect Registration Exams, something he says completely changed everything. He was on purpose again, not just "pushing paper" and feeling disconnected. Rediscovering his passion for architecture came through a simple shift in mindset and an appreciation for his developmental process as a professional.

Today Michael is a licensed architect. He also founded the Young Architect website, a blog that now inspires and encourages countless emerging professionals in architecture. His passion for embracing the process in architecture career growth has now become his day-to-day mission and purpose, using what he has overcome in his long journey to help guide others through theirs. Whether it's helping thousands of aspiring architects pass their Registration Exams or mentoring a struggling student, Michael's brief low-point at the beginning of his career has turned into a fruitful calling.

When we identify something we don't like in our life or career, it's easy to dismiss or overlook it. For two years, Michael Riscica struggled with life as a professional, he was in a funk that he could not manage to get out of. How could it have been that something he loved so much had become such a drag? His issue ended up being a flaw in his perspective, he was looking at his situation in the wrong way. Once he reframed his view about his path in architecture, everything changed, and he suddenly recaptured his purpose.

“I realized that I don't have to be perfect. All I have to do is show up and enjoy the messy, imperfect and beautiful journey of my life.”

- Kerry Washington

So how do we address a dwindling passion in our work or in architecture? There are many ways. For some, it's looking at what we are doing within the field, perhaps the traditional path is not for us. It might be time for us to take stock of what it is we really love to do just as we learned from Julia Gamolina. Or for others, it may be time to pursue more growth, maybe work has become monotonous, and you're ready for a new challenge. And still, many of us simply need to look at our situation in a new light and in a fresh way. As we saw with Michael Riscica, sometimes our perspectives have flaws and need to be corrected. Whatever the case may be, it's pause and reflection that often enables us to rethink why we've set out to do something. Deep down, most of us chose architecture for a reason, let's recapture what we set out to achieve, and hopefully rediscover our passion for that mission.

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

3 Featured Comments

(separated from the previous post to break down the reading and subject content)

Re: work v inspiration (similar to “passion,”)

The advice I like to give young artists, or really anybody who'll listen to me, is not to wait around for inspiration. Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work. If you wait around for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work. All the best ideas come out of the process; they come out of the work itself. Things occur to you. If you're sitting around trying to dream up a great art idea, you can sit there a long time before anything happens. But if you just get to work, something will occur to you and something else will occur to you and something else that you reject will push you in another direction. Inspiration is absolutely unnecessary and somehow deceptive. You feel like you need this great idea before you can get down to work, and I find that's almost never the case.

- Chuck Close

great summary

The hard part is knowing if you have actually hit a ceiling or if the problem is the profession. Sometimes the answer to both questions is yes, and that is when hard choices get harder...

Passion is difficult as a word in our slightly woke culture because it presumes constancy of intent. We admire people who don't give up and keep at it without wavering. 40 years in the desert kind of thing. Reality for most people, and especially creatives, is constant doubt, fear, and worry, ad we all know it. No wonder passion is becoming a dirty word, a word of accusation, implication of failure.

Instead of having passion might be better to be pig-headed, stubborn, focused (whatever that means), or in self-help speak "goal-oriented" (ick). Those traits help us to get through the hard slog of what our job is actually about. Which isn't pretty. Architecture is nothing like school, which it turns out was a kind of sprint practice preparing for what turns out to be a massively long endurance run where we have to keep on learning new things and picking up new skills - to the extent that we eventfully wander into new professions in the course of our daily work.

After a decade of professional practice we suddenly find ourselves to be communication experts or graphic designers, accountants, managers, bim-mers, writers. Some of us may do drafting still, but after 10 years that is not so common, and even fewer of us are doing design, at least not the way we thought we would (cuz the reality is that all of the above are part of the design process). The disconnect from where we started out is so crazy in its enormity. How can we NOT be confounded, especially after our education only hints at this process?

The question is... do we quit when we start going down one of these odd paths, and are aware enough to see it coming, or do we wait until we are well and truly in it and hating it entirely? (If you love the whole thing regardless its not a problem). When life is hell because you feel like your wasting your time on this planet then its time to move on. Either to another company or a different profession.

It might help to know that architecture is not always about design and most time is spent working hard doing tedious things. Much more than school even hints at. Our professional education could help by making that an explicit part of the curriculum. That way it isn't so disappointing, or confusing.

As a final thought, it is not impossible that the problem with the passion question is simply that you don't know enough to know you don't know anything. This is probably a question that cannot be answered until you have worked for a few (or several) years.

You won't find many fields now where professionals don't have drains on emotional reserve, for the same or similar reasons—long hours, limited control, tedious and often questionable tasks. Doctors in HMOs, lawyers in large firms, etc. In my case academia, large schools, where I taught overloads in what, though it had its rewards and I liked the students, was essentially factory line work. In all these cases, the fields have limited ways of looking at life and even the profession itself, and limited ways of talking about both, now more than ever. Few creative types make much money at all, and even the best can't find much of an audience. Writers, for example, have to face bottom line pressures from the corporate publishing houses, who place severe restrictions on what they'll take. Artists who do get attention and make big $ likely have been corrupted by a similar star system.

You can always read, inside your field and outside. This broadens, builds perspective, and restores faith. Maybe some of it will eventually filter into your work.

You can write to develop and refine ideas and tastes. You have a resource at Archinect in the comments sections to pursue interests and state arguments. Put some time and thought in these, and give yourself a chance to mature. Or maybe you'll come up with a piece they'll publish. You have potentially a vast audience here, something most writers don't have. (I've heard NY Times book reviews don't see many eyes.)

You can develop your own projects, at least virtually. You have the skills, experience, and CAD program. There is much dissatisfaction here with current work, with cause. With your own project you can take a stand, define the next movement. I'd be interested in seeing a clearing house of such projects.

Where to find the time? I don't know how I did it, but I did, with reading and writing, and these sustained me over all the years and still do. The other way to look at the problem is where you'll be in x decades if you don't nurture the passion.

You have to practice and give all this time to develop. But the time finds itself. Sacrifice, of course, is needed.

All 15 Comments

I always wanted to be in design rather than production - what to do? I create made up projects on weekends where I can do the design.

How about you spent that energy in competitions lol

so basically you have no personal life outside of architecture/design.

quoting van gogh and marie curie seems like trolling... vg a deeply sad person and unsuccessful in his lifetime; mc literally killed herself with her work.

anyway, i think as a starting architect (or anything, really) you need to keep your mind on the big goal and look at the day to day work as part of a process of learning and exploring. if you hate it, that's useful information too.

and everyone should quit their job after about 3-4 years and work somewhere different. it's too hard to get a full experience of the range of roles staying in one office. maybe you will choose to go back later, but the time away will really let you grow your capabilities.

VG having a sad life doesn't mean he wasn't passionate about his work. And neither does MC working hard...

Definitely agree mostly on your other points though.

right, but i think those two examples show to an extreme the shortcomings of passion as a subjective qualifier for the value of a job. you recently posted another piece on that topic.

I see. You’re saying that the fact that they “had a passion” for their work did not actually end up giving them a better life in the end? Therefore showing that a passion for one’s work is not an end all be all in terms of life fulfillment? I get that.

First, why the reference to people who were mentally unhealthy by today’s standards as a implied norm for contemporary behaviors?

Passion is a dangerous word. Too often it’s used to describe why you have “failed.” Specifically, it’s used by others to explain (justify) why you’ve failed them.

- You don’t have the passion I’m looking for because you only work 65 hours/wk for the equivalent of 35 paid hours.

- You don’t have passion because you don’t talk about the contrapostic nature of user centric construction and the continued exchange of extraction products properly.

-and Q: what if your lack of passion is really burnout because you worked 65 hour weeks to prove you were passionate in a dead end situation (because someone else decided you weren’t passionate)?

So when I hear conversations about passion as a requirement I get worried because it it sets people up to think they have failed, instead of learned and evolved past the original thought.

Forget passion- do the work and pay attention to what it’s telling you.

Aside from the reference to two historical figures who made relevant contributions to their field, I don’t see the issue here. Sure, passion can be a “dangerous” word, and may suggest a lack of desire to work. But, as with the contemporary examples presented, the focus here is really in rekindling ones love for architecture if it begins diminish.

Most of your points I’ve addressed/explored in previous articles (I.e. burnout, etc.). But we could talk about hypotheticals all day. Where is the “conversation on passion as a requirement” here? Someone seeking to enjoy their work in life or better align their path in a way that gives them more joy/purpose is not such a grim endeavor.

And nothing discussed here puts an emphasis on not “doing the work” for the very reason/point you bring up here.

(separated from the previous post to break down the reading and subject content)

Re: work v inspiration (similar to “passion,”)

The advice I like to give young artists, or really anybody who'll listen to me, is not to wait around for inspiration. Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work. If you wait around for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work. All the best ideas come out of the process; they come out of the work itself. Things occur to you. If you're sitting around trying to dream up a great art idea, you can sit there a long time before anything happens. But if you just get to work, something will occur to you and something else will occur to you and something else that you reject will push you in another direction. Inspiration is absolutely unnecessary and somehow deceptive. You feel like you need this great idea before you can get down to work, and I find that's almost never the case.

- Chuck Close

Great quote! This is about inspiration which I see being different from a passion/purpose/fulfillment in one’s work, which is the focus here. But, nevertheless, a valid point for those in architecture.

"Creativity is the Enemy" - T.S.

Concerning Van Gogh: there’s no diminishing his mental illness, unfortunate events in life, and his ultimate suicide. The point of using him in this context is to show, that if anything, it was painting that gave him great joy. It was what he deeply loved and had a sincere and genuine passion for.

With all of the heartache and pain he experienced, painting gave him an outlet (if only minor) away from these other dark aspects. The one sentence/quote concerning from him is to contrast the almost entirely positive anecdotes presented within the main text here. Im sure someone will still find issue with that but consider this a footnote of sorts.

"putting their narrative and their story at the forefront"

See this shit right here is what I despise about Architecture specifically and design in general: at all levels it is about personal marketing, creating a brand, instilling a sense of inevitability about you and your work.

It helps, of course, if you can be interesting and exotic but still accessible, the last thing you want is to challenge people, but instead you want them to think "hey if I have this person around my office they'll contribute to the sense of sophisticated intellectual design luxury I'm trying to cultivate and more importantly they'll make me look good to my friends and peers." Woe betide the student who has a boring narrative or story, and if you're also ugly, unfashionable or sin of all sins, poor? May god have mercy on your soul

Why is this comment hidden?

Great quote!

With all due respect this just might be a difficult article to write 3 years out of school. It's a very thoughtful subject to approach though. Most will just bury it deep and writhe around for the rest of their careers.

Definitely a tough and dense topic indeed. Thanks for commenting.

Exactly. Respectfully, your idea of architecture is purely academic as you've not not had enough experience to know what "passion" even is in this profession. At the least you may want to collaborate with more experienced architects while writing these.

Thanks for the feedback. What did you think of the collaboration within this article with the two “more experienced” professionals?

Sean, why are you hiding my comments? lets be a bit more mature about this. What I am trying to say is that these architects you have interviewed may not be in the gamut of "experienced". There are many more that have been in the profession much longer and still have ups and downs regarding passion. You do bring up a good subject, Im just suggesting you need more of a range of subjects.

sameolddoctor, appreciate the response. what are we being immature about here? I'm interested in your thoughts on the subject. While I don't think you know me personally enough to assume so certainly to know what my experiences have or haven't been throughout my life, I do 100 percent agree that I, as one person cannot know the vastness of what passion means for a whole profession. I don't think any single article could capture such a broad topic. The aim here, as you suggest, is to explore how this broad issue played out in the lives of a couple of people. But, by nature, this leaves out many other cases. Perhaps, for a future piece exploring a larger extreme may capture a larger audience. Someone close to retirement maybe and someone earlier on in their journey.

great summary

The hard part is knowing if you have actually hit a ceiling or if the problem is the profession. Sometimes the answer to both questions is yes, and that is when hard choices get harder...

Passion is difficult as a word in our slightly woke culture because it presumes constancy of intent. We admire people who don't give up and keep at it without wavering. 40 years in the desert kind of thing. Reality for most people, and especially creatives, is constant doubt, fear, and worry, ad we all know it. No wonder passion is becoming a dirty word, a word of accusation, implication of failure.

Instead of having passion might be better to be pig-headed, stubborn, focused (whatever that means), or in self-help speak "goal-oriented" (ick). Those traits help us to get through the hard slog of what our job is actually about. Which isn't pretty. Architecture is nothing like school, which it turns out was a kind of sprint practice preparing for what turns out to be a massively long endurance run where we have to keep on learning new things and picking up new skills - to the extent that we eventfully wander into new professions in the course of our daily work.

After a decade of professional practice we suddenly find ourselves to be communication experts or graphic designers, accountants, managers, bim-mers, writers. Some of us may do drafting still, but after 10 years that is not so common, and even fewer of us are doing design, at least not the way we thought we would (cuz the reality is that all of the above are part of the design process). The disconnect from where we started out is so crazy in its enormity. How can we NOT be confounded, especially after our education only hints at this process?

The question is... do we quit when we start going down one of these odd paths, and are aware enough to see it coming, or do we wait until we are well and truly in it and hating it entirely? (If you love the whole thing regardless its not a problem). When life is hell because you feel like your wasting your time on this planet then its time to move on. Either to another company or a different profession.

It might help to know that architecture is not always about design and most time is spent working hard doing tedious things. Much more than school even hints at. Our professional education could help by making that an explicit part of the curriculum. That way it isn't so disappointing, or confusing.

As a final thought, it is not impossible that the problem with the passion question is simply that you don't know enough to know you don't know anything. This is probably a question that cannot be answered until you have worked for a few (or several) years.

Will, thank you so much for such a well thought through response and for adding to the discussion. I love your insights and feedback!

Falling in and out of love or passion is not the issue, that happens in every aspect of life if your lucky. The issue is how schools set most people up for failure. Look at what Michael Riscica says:

He fell in love with the studio experience, of designing elaborate fictional works of architecture, with learning the theory of architecture. "I wanted nothing more than to live in this imaginary world forever,"

Who can't see that the fictional world of school is, well...fictional? If schools immersed students in the actual process of architecture from day one, they might better be able to retain their passion (or like) rather than get easily disillusioned. As Will said, "architecture is not always about design". True, but so many decisions have design aspects that get dismissed because of their practical nature. If they where embraced from day one in coordination with what we call the 'higher' functions of an architect, they would not only be more valuable to employers, but would take more pride in the craft of architecture, which takes a life time to master.

Schools fail to prepare us by dismissing the client's needs as uninformed, the public's needs as superficial, the developers needs as corrupt, and the municipalities requirements as a burden. Rather than different facets of a larger problem to be solved in concert, they are segregated like a caste system, in part for production but also because of the misplaced priority schools place on conceptual and ideological matters, while aesthetics tend to be circumscribed by the orthodoxy against anything but modernist styles. The real world is much more heterodox and diverse than schools make it out to be.

You won't find many fields now where professionals don't have drains on emotional reserve, for the same or similar reasons—long hours, limited control, tedious and often questionable tasks. Doctors in HMOs, lawyers in large firms, etc. In my case academia, large schools, where I taught overloads in what, though it had its rewards and I liked the students, was essentially factory line work. In all these cases, the fields have limited ways of looking at life and even the profession itself, and limited ways of talking about both, now more than ever. Few creative types make much money at all, and even the best can't find much of an audience. Writers, for example, have to face bottom line pressures from the corporate publishing houses, who place severe restrictions on what they'll take. Artists who do get attention and make big $ likely have been corrupted by a similar star system.

You can always read, inside your field and outside. This broadens, builds perspective, and restores faith. Maybe some of it will eventually filter into your work.

You can write to develop and refine ideas and tastes. You have a resource at Archinect in the comments sections to pursue interests and state arguments. Put some time and thought in these, and give yourself a chance to mature. Or maybe you'll come up with a piece they'll publish. You have potentially a vast audience here, something most writers don't have. (I've heard NY Times book reviews don't see many eyes.)

You can develop your own projects, at least virtually. You have the skills, experience, and CAD program. There is much dissatisfaction here with current work, with cause. With your own project you can take a stand, define the next movement. I'd be interested in seeing a clearing house of such projects.

Where to find the time? I don't know how I did it, but I did, with reading and writing, and these sustained me over all the years and still do. The other way to look at the problem is where you'll be in x decades if you don't nurture the passion.

You have to practice and give all this time to develop. But the time finds itself. Sacrifice, of course, is needed.

I should add one more. Study buildings. Any building, every building, past and present. Appreciate/interpret/criticize/rant. This develops you in countless ways. One of the complaints against current writers is that they haven't read deeply and don't look back at what has been done before. They have blinders on, as if whatever is current is all that matters.

While other fields have their drudges, architecture is uniquely positioned at the intersection of so many different things -- art-adjacent, building, urbanism, politics, sociology, economics, craft, etc. The career trend is usually towards some kind of capitalist-minded specialization, there is no law against using your extra time (ha) to develop the other sides of architecture that you don't get paid for. And then thinking about how that side-interest can connect back to and enrich your career.

Related perhaps, in particular to some of Marc's comments about the idea of failure...?

"By keeping us focused on ourselves and our individual happiness, DWYL distracts us from the working conditions of others while validating our own choices and relieving us from obligations to all who labor, whether or not they love it. It is the secret handshake of the privileged and a worldview that disguises its elitism as noble self-betterment. According to this way of thinking, labor is not something one does for compensation, but an act of self-love. If profit doesn’t happen to follow, it is because the worker’s passion and determination were insufficient. Its real achievement is making workers believe their labor serves the self and not the marketplace."

Great link and analysis. Capitalism is all about the myths of Ayn Rand, riding on someone else’s shoulders, and sociopathic behavior. “Happiness” has been reduced to mere economic survival and if you fail to escape the myriad predators it’s your own fault.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.