A success among urban planners but a failure among architects (with the exception of Eero Saarinen, who used them in his prototype modeling stages), Modulex—the architectural modeling Lego-offshoot—was largely shuttered by the 1980s, almost revived in 2015, and now serves as an XS cult classic in architecture.

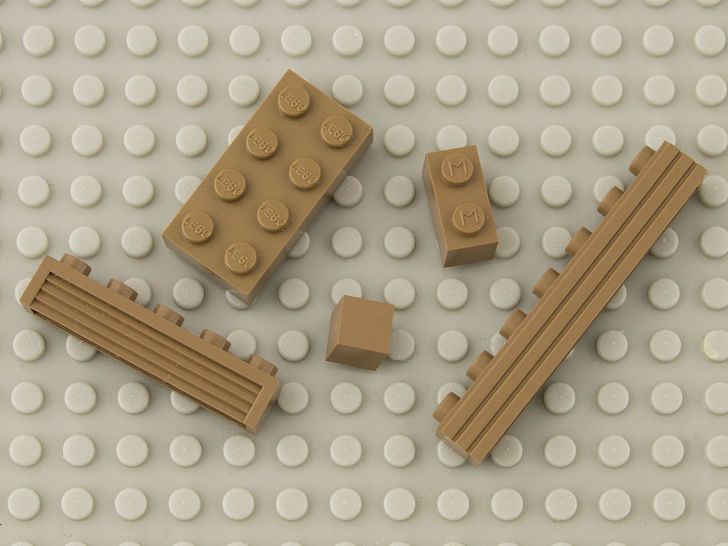

Spend enough time delving into the YouTube backwaters of specialty modeling materials, and you will undoubtedly discover lengthy tributes to Modulex, a series of precisely they mostly failed to catch on with architects when they were released.dimensioned, scalable plastic bricks launched in 1963 by the owner of Lego, Godtfred Kirk Christiansen, in collaboration with industrial designer Jan Trägårdh. At first glance, they appear to be simple miniatures of their parent block. But the Modulex line of bricks, which were based on a 1:1:1 cube (five millimeters on each side) instead of the 10:5:3 ratio that made up every Lego brick, were also detailed and adaptable in a way that ordinary Legos were not. Some featured frieze-like detailing on one side and a hollow center to make more nuanced modeling possible; sets came with trimmable blocks and model bases. And yet, they mostly failed to catch on with architects when they were released.

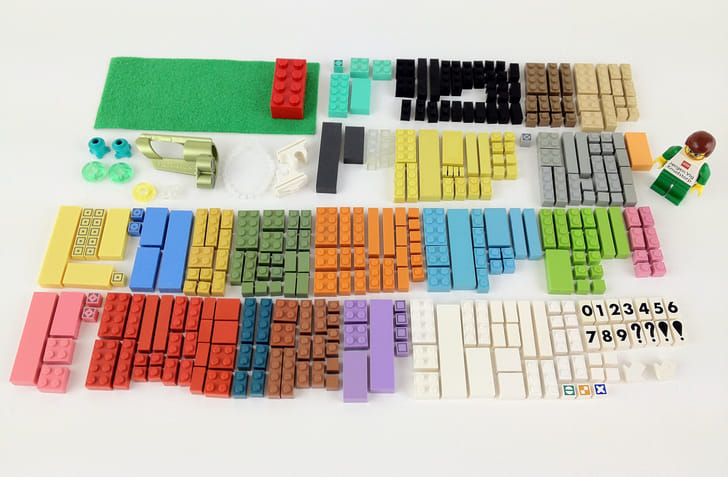

Instead, urban planners and corporations like The Bank of England and General Motors began to use them to construct large-scale models of proposed projects. Because they were relatively easy to assemble and modify, Modulex were great for quickly conveying planning ideas to visitors in an era when a supercomputer was the size of a garage and had the processing power of a calculator. Their scalability made them ideal for constructing city-wide models or intimate surveys of individual projects, like a prefabricated diorama (although they were not compatible with traditional Lego bricks). They came in a variety of colors commonly used in construction at the time, allowing for realistic, if limited, portrayals of projects.

the pieces sprang from a mentality that was rooted in an older, more predictable design worldHowever, they also possessed a certain raw, abstract quality that made them undesirable for use in finished professional models, which is part of why they were generally used by professionals acquainted with design, as opposed to design professionals. Indeed, their formulation within the orthogonal era of modernism and brutalism made them more suitable for a brick-based design sensibility than the aerodynamic forms that were to blossom in postmodernism’s conceptual soil. As Barney Main, Lego enthusiast and author of “Saving Modulex” notes, a component-based system is inherently a flawed idea for a professional modeling set. It automatically limits the nuance of the design to a clunky, inflexible plastic atom. Although the set did have the potential to incorporate curves and other non-linear elements through clever gluing and modification, the pieces sprang from a mentality that was rooted in an older, more predictable design world. As Main explains, “the seams between the bricks convey a distinct vibe of LEGO, which looks unprofessional. This is heightened by how rarely bricks and mortar are used in modern construction: a steel and concrete building has an entirely different texture.”

What other factors prevented the blocks from wider architectural acceptance? Some, such as Main, blame Lego’s marketing strategy, which included equal parts scolding (“The Modulex planning model is realistic and clear. It represents the result of many hours of study and discussion – but it has not yet had its day – in the future when decisions have to be made on new layouts and extensions, these can be made quickly”) and corny rhyming verse (translated from a German-language ad, “The smiling father has discovered / That his son will be an architect someday!”). Much like the limited component thinking, the use of this kind of narrative in a more culturally diverse, postmodern marketing world tagged Modulex as quaint at best and, at worst, painfully out of touch.Plancopy’s straightforwardness was a commercial hit

By the 1980s, the Modulex set began to shift exclusively toward modeling signage, morphing into something known as “Plancopy.” Instead of scaled bricks, tiles with individual characters were used to label and number models. These letters, numbers and symbols, produced in a variety of alphabets, could be placed precisely on a grid but also allowed for customization. Unlike the more conceptual yet limited Modulex, Plancopy’s straightforwardness was a commercial hit.

Again, Plancopy flourished in a vacuum of easy technology; typography and printing were industries staffed by professionals who had not yet been made redundant by the advent of the personal computer and home publishing. The Plancopy set allowed planners to quickly formulate a variety of signs and office organizational hierarchies, and was produced up until 2004. The miniature ultimately gave birth to the macro: Modulex went from being a tiny plastic block to a massive real-world signage company with three separate divisions, all of which specialize in creating custom signage and brand identities for different environments.

But what of the original meticulously crafted sets of bricks and snap-to accessories? Original sets of Modulex, most of which have attained the patina of vintage board games whose cardboard box corners have been worn down by frequent use, are now nostalgic rarities fondly traded and displayed among connoisseurs. Currently, a 1965 Modulex M20 set is going for $295.50 on eBay. They are shown at collector fairs and discussed in online forums. However, they still occasionally are sought out for the purposes of model building: on Archinect’s Forums in 2010, a Modulex seeker posted, “If you have any in an old storage closet (or know someone who might), please let me know. I'm trying to acquire as much as I can (will buy it from you) for some large models I am building.”

Interest in the old sets had reached enough of a peak that in 2015, Modulex Bricks A/S announced on Facebook that it was going to start producing the bricks again, but shortly thereafter Lego stepped in and bought back the rights to the bricks, quashing hopes for a revival. “It has been important for the LEGO Group owner family to ensure historic rights stay within the owner family,” a statement from the owner of Modulex Bricks A/S read. “The potential to produce Modulex bricks has also been addressed and there are no plans to manufacture Modulex bricks in the near future.” As a commenter on MiniBricksMadness.com frothily noted in light of the email, “All test bricks, moulds, and materials that Modulex Bricks A/S was in the possession of, have been turned over to The LEGO® Group as part of the agreement. Which means, anyone who was given some of the re-issue test bricks has some very rare bricks in their possession!”

For the time being, it seems that there will be no new Modulex, just the aging, handily-ratioed bricks that never quite scaled up to their potential.

This piece is part of November 2016's editorial theme, XS. Submit to our open call here.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.