The difference, in English, between the words “electric” and “electronic” is subtle but powerful. A simple definition might go something like: “electric” refers to things that use electricity as energy, while “electronic” is used to describe things that use electricity as a means to manipulate information. Therefore, a lamp is an electric object, but an email (previously e-mail) is an electronic letter. And yet, in the context of architecture, a field often troubled by semantics and syntactic nuances, we often take for granted our media’s relationship to electricity. Despite their reliance on electrical light, for instance, our drawings are still drawings, not e-drawings or i-drawings or any other variant that could separate them from mechanically produced media. Moreover, today the main difference between drawings, images, and photographs is simply derived from what file extension is used to format them.

But this flattening of media into file formats presents a radical paradigm shift in architectural design. At least, that’s John May’s argument in his recent book, Signal. Image. Architecture. (Columbia, 2019). In this pocket-sized treatise, May—who is a co-founder the design firm MILLIØNS with Zeina Koreitem—doubles down on an earlier piece, which was aptly titled “Everything is Already an Image,” lengthening and strengthening his argument that we are enmeshed in a culture of signizaliation and imaging. Building upon the work of contemporary philosophers like Bernard Stiegler and Bruno Latour (who, also contributed the foreword), the result is a highly compact, provocative analysis of architecture’s ongoing negotiation with (1) imaging technologies and (2) its own traditional disciplinary knowledge (drawing).

May even provides a short summary of these dialogues early in the footnotes. In short, he claims, architects today do not produce drawings, they produce images. And because our media is primarily image-based, architects must engage with the psychosocial implications of imaging as a new technical regime. Fair enough. Done. Debate no longer if a JPG is a drawing or not (it’s not). But what stands out most in my reading of Signal is the wide lexicon of portmanteaus that May relies on to emphasize his points, such as mnemotechnics, automnemonics, psychogestural, postorthography, pseudorthography, and many others. Both obscure, yet precise, these terms are used to describe knowledge, phenomena, and perceptions that travel across disciplinary boundaries. Etymological hybridization is crucial for May as he is operating at a register of abstraction and philosophy that is neither purely technical or political but technopolitical and neither psychological or social but psychosocial.

Despite their reliance on electrical light, for instance, our drawings are still drawings, not e-drawings or i-drawings or any other variant that could separate them from mechanically produced media.

The real crux of May’s book is the tension between signalization and what he calls pseudorthography. Signalization is relatively straightforward; it is the energetic translation of electrical impulses to readable data, the process by which things become electronic. Pseudorthography, on the other hand, is a bit more obscure. May defines it as the “residual psychology of orthography laboring in the absence of its own technical-gestural basis—a pathology in which familiarity, that crucial element of comprehension, is preserved as a coping mechanism in the face of completely unfamiliar conditions.” In other words, pseudorthography is both a remnant of previous familiar knowledge (e.g., drawing) and a simulation of that previous world presented on a screen (e.g., a virtual drafting table; a skeuomorph). The tension driving the argument in Signal can thus best be seen in architects’ mischaracterization of images as drawings, but also in their insistence on the relevance of drawing itself.

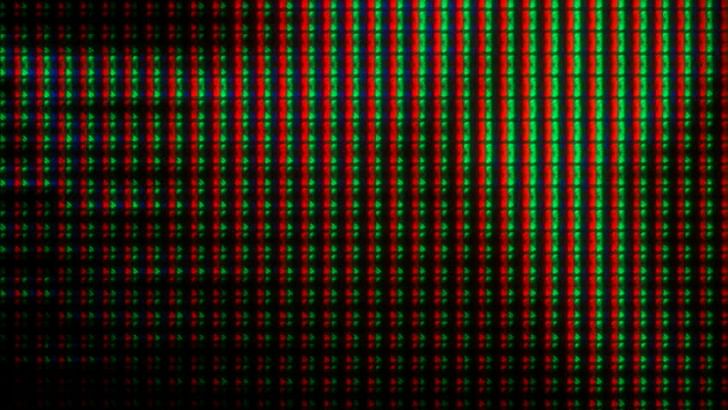

What May makes exceptionally clear is that our dependence on false orthography prevents us from fully exploring the world of signalization. In describing pseudorthography as a “coping mechanism,” May exposes architecture’s unwillingness to let go of drawing. He describes a generation loyal to an “imagined ‘culture of drawing’” of which they are not really a part, as most architectural media today exists in image form. Architects translate between RGB and CMYK color values more often than they draw straight lines with a T-square; they synchronize their BIM model more often than they sharpen their pencils; they scroll through Instagram more often than they visit the library. In short, architects work in the world of signalization, but because it is experienced through a simulated form of orthography, they have yet to engage fully with the politics, technics, and matter that constitutes our new statistical-electrical and software-based planet.

If its fate is not death, what happens to orthographic thought after architecture is no longer primarily concerned with it? If orthography is abandoned by its parent, where shall it seek shelter?

At this point any further mention of drawing’s importance in the world of images will sound stale and stubborn. But it would be too easy (perhaps silly) to suggest that May is announcing the Death of Drawing as Barthes announced the Death of the Author. Instead, Signal encourages architecture to reorient itself and reassess its position as a technosocial practice. And I agree with most of May’s points. Still, I can’t help but wonder what happens to orthography after signalization. After all, it has been architecture’s bread and butter for centuries. If its fate is not death, what happens to orthographic thought after architecture is no longer primarily concerned with it? If orthography is abandoned by its parent, where shall it seek shelter?

To me, these questions are the biggest takeaway from Signal. Personally, I’m not too concerned with the project of imaging. Architects and designers are already engaging signalization, some better than others. I question the future of orthography not because it is some kind of transcendent piece of architectural knowledge that must always be there, but rather because it has some applications which imaging does not. For instance, the space of Internet browsers (as opposed to the content) functions primarily orthographically; we browse pages up and down, forwards and backwards. On screens, we move through and experience content in an infinite XY plane, maneuvered through orthographic gestures. Though discretely arrayed color values make up the material of LCD screens, mice, touchpads, styluses, and pressure sensitive surfaces that allow us to interface with electronic media could all be understood as orthographic technologies.

And so while architecture might be transmogrifying itself more and more into an imaging discipline, orthography, as “geometric gesturing that arranges marks into legible lines and texts,” might be better suited for describing our gestural—dare I say, bodily—relationship to interfaces, the immaterial structure of screen-spaces, the diagrams of surveillance systems and other emerging abstractions of digital life. To move beyond drawing does not mean to lose our own foundational knowledge, but rather to redirect that knowledge as necessary in our new technical regime. Yes, architects do not produce drawings anymore, nor are drawings used to build buildings, but architects do point, click, drag, scroll, and swipe—electrically charged geometric gestures as significant as any drawn line.

Galo Canizares is a designer, writer, and educator. He holds an M.Arch from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and teaches at The Ohio State University’s Knowlton School of Architecture. His ongoing work concerns the production of architectural media after the rise of digital culture.

1 Comment

Great article! I really need to buy the book now.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.