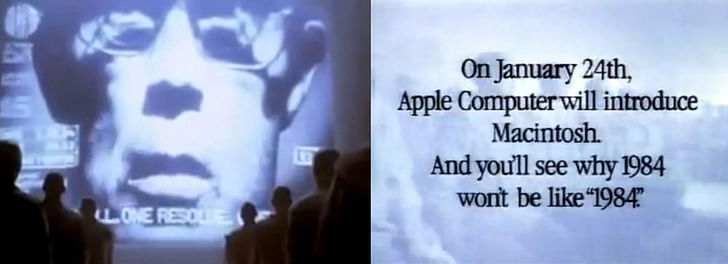

The U.S. Census confirms it: as of 2016, 89 percent of American households own a computer. According to the report, this represents an 81 percent increase from 1984, the year of Apple’s now-famous Super Bowl ad and the release of their first Macintosh. The numbers are pretty clear. Seeing as most daily tasks require some interaction with software, from banking to setting your alarm, it makes sense for households to own at least one whirring box of circuit boards.

Less clear, however, is what exactly constitutes a “home computer.”

The previous decade’s homogeneity of tan desktops, with matching keyboards, mice, and cathode-ray tube monitors, has been replaced by an assortment of backlit devices that come in all shapes and sizes. To reconcile this, the U.S. Census Bureau divides computer into smartphones, desktops and laptops, and tablets, making it difficult to determine the precise role computer plays in the domestic sphere.

A significant omission in the survey is any mention of domestic accessories that are not quite office appliances nor portable touchscreens, those Internet of Things devices that update us on the weather and order refills of Tide Pods. These overlooked objects have had perhaps the most unexpected effects on domestic life. I’m not necessarily talking about the foibles of e-locks and app-controlled light bulbs (though those do seem to glitch in hilarious ways), but rather the influence of smart televisions and voice assistants. While desktops, laptops, and smartphones allow us to interface with all kinds of software, these smaller machines are more narrow-minded and are actively disrupting domestic tasks. Smart televisions stream media, intelligent thermostats allow homes to be remote-controlled, robot vacuums clean up after you. They promote efficiency and erasure of the traces of daily life. As a result, these gizmos are turning the home into one giant piece of sterile software.

In a way, this is what we’ve always wanted. If science fiction is a litmus test for our technological desires, then robot vacuums and sterile environments were always the plan. In the movies, artificial intelligence is often portrayed as a domestic servant. Iron Man has J.A.R.V.I.S (So does Mark Zuckerberg) and Dave has HAL 9000. Even computing pioneer Alan Turing envisioned machines being subservient to us: “the intention in constructing these machines in the first instance is to treat them as slaves, giving them only jobs which have been thought out in detail.” Despite Turing’s insensitive metaphor, the imagery he conjures clearly illustrates his position on human-machine dynamics.

This brings us, once again, to the mention of the year 1984 in the U.S. Census survey. Aside from being the only date mentioned in the summary outside of 2015 and 2016, 1984 is far too uncanny to be accidental. It was the year Apple introduced the Macintosh 128K, one of the first consumer-level computers to feature a graphical user interface (GUI), as well as the newly invented 3.5” floppy disk drive. Apple announced this watershed moment with a Super Bowl ad, an homage to George Orwell’s 1984 directed by Ridley Scott, who at the time was fresh off the set of Blade Runner. Put simply, the beginning of home computing was marked by the convergence of sci-fi imagery and consumer electronics.

The rate at which science fiction becomes science fact has indeed quickened in the past thirty years.

Today, each new home gadget evokes some kind of sci-fi trope, whether it is voice control, wearable tech, or autonomous vehicle. But today’s devices also suggest a shift towards new domestic behaviors. Voice activated refrigerators, ovens, and televisions may seem like a fantastical luxury, but so did smartphones not so long ago. Putting sci-fi aside, is it possible to imagine what the home as a seamless interface might look and feel like? How might the politics of the home change? Would walls get thicker or thinner? Samsung has already announced “The Wall,” a 146-inch LED television that would surely be an architectural feature in any home. Does this suggest the digitization of all interior surfaces?

Though not completely digital (yet), the home is already an interface. Doors are switches, wall outlets provide energy, vents filter your air. Reyner Banham described this “baroque ensemble of domestic gadgetry” as the “junk that keeps the pad swinging.” Maybe we need to know less about specific devices and more about the behaviors and spatial effects they engender. How, for instance, the digitization of home entertainment affects room structures, or how the rise of package thieves leads to front-door paranoia and new pseudo-public amenities like Amazon lockers.

The rate at which science fiction becomes science fact has indeed quickened in the past thirty years. However, as the popular adage goes (and the U.S. Census corroborates), the future is not evenly distributed. Home computing connotes a different set of behaviors in different households. WiFi not only changed the spatial mechanisms of computing but also opened the door to a slew of new habits and priorities that warrant more attention. Hotspots may exist as yet another building system, but they also index portals to other worlds. Dead zones, on the other hand, can betray construction faults, or the age of a building, and are often popular causes of frustration. Today, house plans might not solely reveal a set of spatial configurations, but when overlaid with all of our gadgets, gizmos, and appliances they might also reflect our current relationship to computing in general, from software that keeps track of your finances to home security systems to apps that keep the pad swinging.

1. U.S. Census Bureau, “Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2016.” Accessed January 20, 2019. https://www.census.gov/content...

2. Reyner Banham, “A Home is Not a House,” Art in America, 1965, Vol. 2, NY: 70-79.

Galo Canizares is a designer, writer, and educator. He holds an M.Arch from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and teaches at The Ohio State University’s Knowlton School of Architecture. His ongoing work concerns the production of architectural media after the rise of digital culture.

1 Comment

The home should be a fortress against computer mania. It is as if Winston Smith went down to the Ministry of Truth and bought a dozen or so 'telescreens' to hang on the wall. Aren't you tired of being a 'data point' in several hundred thousand data banks?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.