David Hockney loves to draw on a telephone. Sometime in the late 2000s, he began painting on an Apple iPhone and iPad, and he has not been shy about expressing his enthusiasm for gadgets. He uses them to sketch in the field, to send drawings to his friends, and he even records his process using the Brushes App. The devices afford him new freedoms. He can paint anywhere without equipment and produce infinite iterations. But I doubt any of us would label Hockney a digital artist.

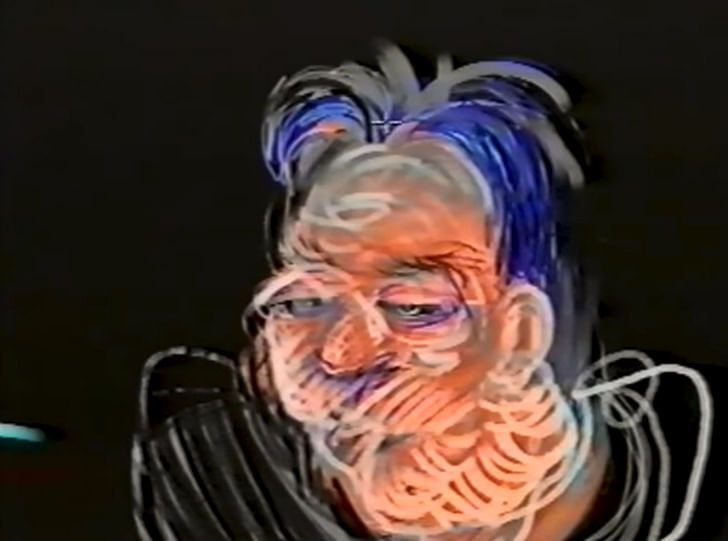

Still, Hockney has an interesting history with painting software. In 1986, the broadcast graphics company Quantel Ltd. invited him to participate in a documentary for the BBC. They would later boast that Hockney was the “first serious artist” to test out their Paintbox software, a kind of precursor to Photoshop geared for professional graphics. During the demonstration Hockney reviews the software, mentioning that using the tablet, pen, and screen is like “painting with light” or similar to producing stained glass art. His unique childlike brush strokes translate seamlessly onto the screen as he scratches the pressure-sensitive tablet with the stylus. The only hiccup is an attempt to mix colors; unfortunately, digital colors do not mix the same way physical ones do.

What appears to fascinate Hockney the most (in the video) is the infinite layering unique to virtual paint. He claims, “you could go on forever drawing.” And this is largely true. One of the advantages of the virtual canvas—in any painting application—is the almost limitless layering of brushstrokes, effects, and filters. Couple this with the portability of mobile screens and it’s easy to see why 30 years later, Hockney’s mobile medium of choice is the tablet. But what exactly does it mean for a well-established painter to dive into digital media?

After a 2016 solo show at the National Gallery of Victoria featuring over 600 iPad paintings, critics appeared to be split on the merits of his digital works. Some noted that the drawings “can never hide their electronic origins, no matter how painterly they appear.” Others praised his experimental enthusiasm. Hockney is established enough that he can easily brush off any criticism. In fact, he has a sense of humour about going digital. He quips: “People from the village come up and tease me: ‘We hear you’ve started drawing on your telephone.’ And I tell them, ‘Well, no, actually, it’s just that occasionally I speak on my sketch pad.’” In another interview, he adds, “Drawing was going out of style, actually...I’m amazed the the telephone can bring back drawing.”

he adds, “Drawing was going out of style, actually...I’m amazed the the telephone can bring back drawing.”

These responses suggest that the artist’s transition from analog to digital has less to do with experimentation and more with convenience. While some artists take up digital media to exploit its mechanisms and reveal the potential of computed colors, Hockney appears just as happy to paint the same way he always has, only on a virtual canvas. Of course, the virtual world can also augment the work. Perhaps the most interesting component of the 2016 exhibition was a series of animated paintings that expose the artist’s process. Brushes, Hockney’s app of choice, contains within it a setting to record every brush stroke, so the final drawing can be played back from start to finish. This allows him to communicate his process and reveal even more of himself through the videos.

Brushes, Hockney’s app of choice, contains within it a setting to record every brush stroke, so the final drawing can be played back from start to finish. This allows him to communicate his process and reveal even more of himself through the videos.

That Hockney would be eager to adopt new digital mediums is already apparent in the Quantel documentary. In it, he frequently repeats his fascination with Paintbox’s infinite layers and the vibrancy of the backlit color palette, comparing it to stained glass. 30 years later, he again describes using the iPad, as “drawing on a sheet of glass.” But it is difficult to characterize Hockney as a new media artist. His enthusiasm for software appears to come from a sincere interest in the convenient effects of the portable screen. And so his relationship to technology is quite quotidian. Like many of us, Hockney picked up a tablet not because it was a revolutionary new medium, but because it was user-friendly and lightweight. It allows him, for instance, to venture out into Yosemite and capture each stage of Winter’s transition into Spring.

Hockney still works with physical paint in his L.A. studio. And while critics nostalgically lament the loss of some material effects in the transition from physical painting to virtual RGB values, he appears to remain committed to both. There are many artists who work across virtual and physical mediums, but Hockney’s case is curious because of his prominence and early encounters with digital painting. In the broader context of media digitization, we could say that he embodies an extremely contemporary creative personality. One that, as Nicholas Negroponte suggested back in 1995, accepts that life relies as much on bits as it does on atoms. Hockney shows us that maybe we don’t explicitly need to distinguish between the self-portrait and the selfie, the telephone and the sketchbook, the final work and the process video, or the series and folder of JPEGs. Drawing on a telephone might even sound less absurd as time goes on.

1. Cory Perkins, “How David Hockney Became The World's Foremost iPad Painter,” accessed June 1st, 2019.

2. “Painting with Light,” video, accessed June 1st, 2019.

3. “David Hockney Current,” accessed June 1st, 2019.

4. Claire Cain Miller, “IPad Is an Artist’s Canvas for David Hockney,” accessed June 1st, 2019.

5. Nicholas Negroponte, Being Digital (New York: Vintage Books, 1995).

Galo Canizares is a designer, writer, and educator. He holds an M.Arch from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and teaches at The Ohio State University’s Knowlton School of Architecture. His ongoing work concerns the production of architectural media after the rise of digital culture.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.