Small Studio Snapshots is a series that focuses on, well, small studios. It's about the reasons why you might set up your own studio, and the things that may get in your way. Sometimes, it can be tough to be a small fish in a big sea—but the rewards can also be supersized.

This week, we're talking to the Los Angeles-based experimental studio MILLIØNS. Founded in 2011 by John May and Zeina Koreitem, both of whom also teach, MILLIØNS considers architecture "a speculative medium for exploring the central categories of contemporary life: technology, politics, energy, media, and information."

How many people are in your practice?

3-4 (2 partners, 1-2 interns)

Why were you originally motivated to start your own practice?

John: Initially we both spent time in various offices and in different cities. I worked for Preston Scott Cohen, and then briefly for Toshiko Mori, on various projects. Zeina worked in the offices of Dominique Perrault and RCR Arqåuitectes. Those were often very intense and valuable experiences, but ultimately we always wanted the challenge of running our own office, and it just seemed like a natural progression when we met.We essentially have no intellectual division of labor in the office

Zeina: We both also find it more interesting to collaborate than to work alone, and that sentiment extends even beyond our partnership to our various collaborators. From the beginning we’ve wanted a kind of collective undertaking in which our individual identities dissolve into the work itself, or are dissolved during the process of making that work. We essentially have no intellectual division of labor in the office, and we can never remember where specific ideas began, or who first motivated them or took them in a new direction. It never matters. Those kinds of rigid identities just don’t interest us.

John: It was also absolutely crucial for us to start our own practice because we are both deeply committed to teaching, and to the idea that the academy provides a crucial space of experimentation, a place for posing questions—technical, representational, sociopolitical, etc.—that simply aren’t yet fit for mass consumption, so to speak. At a certain point it becomes nearly impossible to balance both practice and teaching without establishing independence. And we absolutely feed off the energy produced by the tensions between those two domains.

What hurdles have you come across?

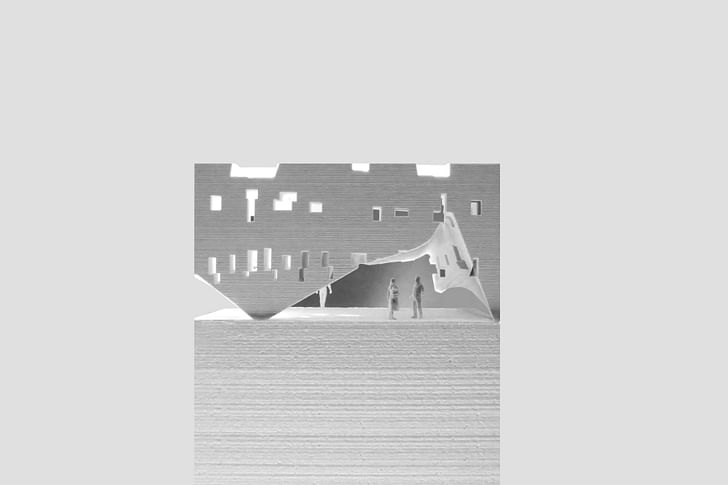

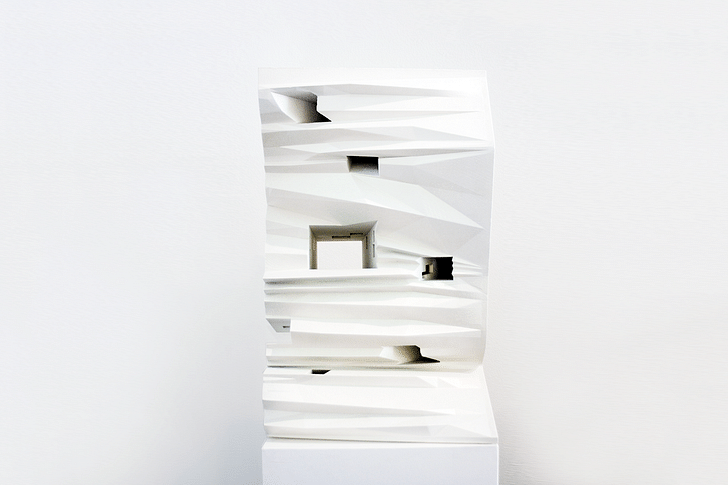

Zeina: There are a whole series of hurdles—budgets, rent, overhead etc.— which are important factors, but they are also common to any small practice, and in that sense are completely cliché and expected. For us, perhaps the more relevant hurdles pertain to certain assumptions about what a young practice should be focusing on, and the ways in which those interests should be represented. We are constantly questioning the tools that architects conventionally use to represent and communicate their work (drawings and renderings produced with proprietary software packages, for example) by immersing our work in instruments and techniques of visualization borrowed from other fields—from experimental computer graphics, open-source software platforms, and various kinds of computer-numerical desktop fabrication tools. We like to combine these platforms, to hybridize them, and even use them in unintended ways, to see how they might challenge or intensify the more typical or traditional forms of architectural production.

Is scaling up a goal or would you like to maintain the size of your practice?

We are constantly questioning the tools that architects conventionally use to represent and communicate their workJohn: It seems that the entire question of “scaling up” has changed quite drastically in our generation. The emergence of “superfirms”—AECOM, Gensler, IBI Group, etc.—has, to some extent, come at the expense of the mid-sized practices that were, for the previous generation, an important avenue for the maturation of earlier experimental work. It seems that architecture is now finally experiencing, post-2008, the kinds of polarization that have defined other sectors of the economy for several decades—between these insanely large firms, which serve the global commercial real estate and risk markets, or the very small “boutique-bespoke” practices, which as we know are generally anathema to any ideas that challenge the taste conventions of their niche clientele. The middle terrain between these two forms of hypernormality has been so drastically reduced that any small practice must thread a very thin needle. This is not to suggest that our situation is somehow more difficult than it was for previous generations, but the terrain has shifted, and the questions are different. For us the question is not so much “do we want to grow?” but rather, “What kind of practice is capable of challenging prevailing cultural lifestyles and political assumptions?” The latter is less a question of size than a kind of tactical-intellectual orientation towards the world.

Zeina: So, would we like the opportunity to engage with larger projects? Yes, of course, but only under the right conditions. For now, we prefer to be patient and to work on more intimate projects—projects that engage the culture of the city, or entrenched patterns of living, and which pose questions that are perhaps outside margins of this now-established notion of boutique practice. One of our current clients, for example, is a new cultural institution, the Los Angeles Museum of Geography, whose mission aligns well with our own desire to question what it means to live in LA today, and to see what it might mean to live differently.¹ So in collaboration with them we are designing a series of pop-up exhibitions, curated by LAMG, that expose the hidden or unseen life of the city.

What are the benefits of having your own practice? And staying small?

John: There’s obviously a tremendous amount of risk associated with this path, but also a tremendous amount of freedom—freedom that allows us to balance our practice with our intellectual pursuits and teaching, and to be selective in the kinds of projects that we choose to take on. We’re able to accept certain projects and commissions—we’ve just completed a single-family home in Upstate New York, for example—while balancing those client-driven projects with more speculative provocations on collective living,² or new thermodynamic ideas,³ or the status of drawing in contemporary architectural production.⁴We are able to invent and structure specific kinds of collaborations with aligned fields

Zeina: We are also able to invent and structure specific kinds of collaborations with aligned fields—film, music, etc.—that permit us to pursue our own interests with a certain degree of freedom. For example we have just recently begun collaborating with a non-profit cinémathèque here in Los Angeles, working towards a kind of multimedia project that would otherwise fall outside the scope of an architecture practice. And while they always put a tremendous amount of stress on our time and resources, it is important for us to have the freedom to explore these kinds of projects.

Do you run a practice with six or less people? Get in touch!

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

3 Comments

Cohen's influence ironically makes RCR's landscapes disappear.

First, I don't know what Josejpullutasig means by that. We work for people who's work we like and who's aesthetics resemble our own, so its not surprising that their work would resemble Cohen's and there's nothing wrong with it. Cohen doesn't have the copyright on crinkled surfaces.

Second, I think the architectural community needs to be more critical of architectural speculation and the validity of its intentions. That said, these guys sound legit in their intentions and I'm looking forward to seeing what they produce in the future. My only comments would be that they may need to grow their office in the future in order to test their experiments in the form of buildings, which we all hope to see happen some day. Also, I think "technology, politics, energy, media, and information" is too broad a range of interests, and that hey would be a force to reckon with if they found a more specific theme. Otherwise, great work! Can't wait to see more in the future.

PS: I think when Zeina says "From the beginning we’ve wanted a kind of collective undertaking in which our individual identities dissolve into the work itself, or are dissolved during the process of making that work..." To me it seems like the second half of that sentence more concisely conveys what she wants, and the first half COULD be read as a contradiction. The rest of the article is uncommonly decipherable for architects (ie: Josejpullutasig)

"Cohen doesn't have the copyright on crinkled surfaces. " +1

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.