Yesterday, amidst the roses, magnolias, crabapples and Littleleaf lindens that populate the White House Rose Garden, the President announced that the United States will withdraw from the Paris Agreement, the landmark international climate agreement made last year and signed by every country in the world except Syria and Nicaragua.*

While the Paris Agreement has its issues (it’s non-binding and largely insufficient), it is widely understood as the first major movement towards addressing an existential threat—the existential threat—that transcends the boundary lines demarcating the nation-states of the 21st century. But these borders resist transcendence. The discord that preceded agreement largely centered on the global inequity of climate change: the countries that will be most affected by it are those least responsible for it. The developed, industrial countries—the United States chief among them—are the greatest producers of greenhouse gases and the best-equipped to address their effects.

But for the President, the victim of the Paris Agreement is the United States. He believes it puts the country at a “permanent disadvantage” with other rising powers. He believes withdrawal constitutes “a reassertion of America’s sovereignty.” “The rest of the world applauded when we signed the Paris agreement,” he said. “They went wild. They were so happy. For the simple reason that it put our country, the United States of America, which we all love, at a very, very big economic disadvantage.”

the built environment constitutes one of the major fronts in the battle for a habitable future

What does this mean for architecture? That depends. Last year, we put together a feature looking at the implications the Agreement has for architecture. Much of this remains relevant since the rest of the world will continue to strive to adhere to its strictures. At the heart of this speculation is the understanding that the built environment constitutes one of the major fronts in the battle for a habitable future. On the one hand, the built environment is where much of the action, so to speak, takes place, whether as flooding or drought or environmentally-induced warfare. On the other, the construction and maintenance of buildings produces the lion’s share of global carbon emissions. And better design can change that.

There are other ways architecture and ecology touch. Here’s a round-up of some of our past coverage of environmental issues and their relationship to the built environment.

Architecture of the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene is a term coined in 2002 by Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen referring to a geological period—like the Holocene or the Jurassic—that is marked by the presence of humans. In other words, it’s when humans constitute a geological force, visibly recorded. The precise starting date for this is debated, ranging from the beginnings of agriculture to the Industrial Revolution to the detonation of the nuclear bomb, but the implications of the thesis are wide. In this series, we try to unpack what the Anthropocene means for architecture, and what roles architecture can have in it.

Here’s part one, part two, part three and part four.

45.2 million people—if not more—are currently displaced by conflict and persecution. That vast number, however, doesn’t include so-called ‘climate refugees’, or people who have been displaced due to environmental disaster. This feature takes a look at the habitations of the refugee, both normative and speculative.

Timothy Morton on haunted architecture, dark ecology, and other objects

“Why can’t we have an ecology for the rest of us, the ones who don’t want to jump into a pair of shorts and hike up a mountain yodeling?” asks the philosopher Timothy Morton in this interview on the implications of his work for architecture. As one of the foremost eco-philosophers, Morton’s perspective is incredibly valuable—it’s also fascinating. Check it out to find out why, for him, “every house is a haunted house”.

Climate change was removed from whitehouse.gov today. What does this mean for architects?

In this op-ed, Katherine Stege ruminates on the ramifications of the removal of the term ‘climate change’ from whitehouse.gov following the election of President Trump. Now, of course, removal from the Paris Agreements can be added to the list.

Ed Mazria of Architecture 2030 also penned an op-ed on what the last election means for sustainable architecture. Here, he outlines calls for actions that can be taken by professional organizations, academics, and practitioners.

One of the most difficult things for climate skeptics to wrap their minds around is how imperceptible climate change is. Jim Inhofe, the senior Senator from Oklahoma, famously brought a snowball to the floor of the Senate, implying that since there’s still snow in DC, the planet isn’t warming overall. This isn’t true. But the difficulty of grasping something you can’t really touch or see remains. In this book review, we look at two different approaches to “seeing in the Anthropocene”.

Shitting Architecture: the dirty practice of waste removal

Not everything ecological is green. In fact, sometime it’s brown. In this feature, the way we relate to our own waste is put front and center. Its thesis is that the way we relate to waste represents a fundamental aspect of our being in the (warming) world.

Come rain or shine: reviving collective urban form with the GSD's Office for Urbanization

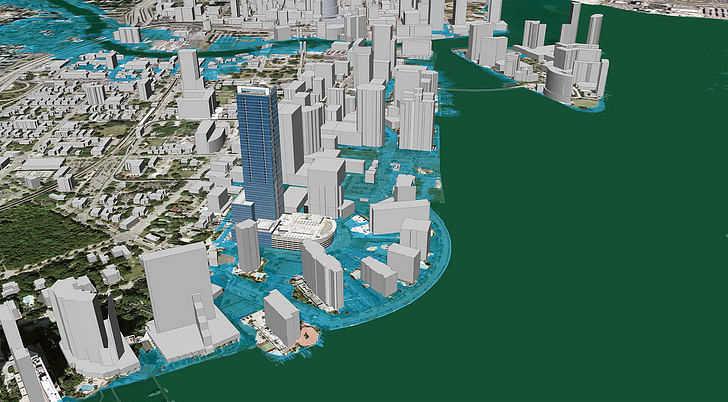

How can academia tackle climate change? Harvard GSD has an answer with its Office for Urbanization, headed by Charles Waldheim. They're currently researching sea level rise in Miami Beach—a region that will be particularly affected by rising tides. Check out this interview to find out more about their work.

While California's water problems have mitigated a bit, its water usage to water production ration remains wildly out-of-sync. As the drought reached crisis levels last year, we hosted a competition to discover ways that architects could address a "dry future". We received a wide range of responses, both speculative and pragmatic, that show off the power of the architectural imagination when faced with existential environmental problems.

Despite what we may like to think, there's no clean line between 'the urban' and 'the natural'. This is a fact on clear display in Los Angeles, a city known for its tendency to "pave paradise." Here coyotes wander the streets while the city's refuse lines its shores. And its river—famous for being forgotten—is at the center of efforts to address the city's complex and conflicted ecology.

For the third iteration of Archinect's recurring live podcasting event series Next Up, we took a look at the LA River—past, present and future.

The effects of a warming planet are manifold. Sea levels are rising. Rivers are drying up. Species are vanishing at unprecedented rates. As these phenomena increase in frequency, there are basically two strategies we can take: relocate or adapt. Along the coastline of Alaska, predominantly-indigenous communities are currently moving their entire communities as the waters rise. The Syrian conflict, which some have attributed in part to climate change-induced drought, has created a refugee population larger than any the world has seen since the Second World War. Meanwhile, in New York, the Rebuild by Design competition has gathered a wide range of architectural strategies to help the city adapt to rising sea levels. Similar actions are taking place in the Netherlands and other regions along coasts (note: the major population centers of the world all cluster along coastlines).

For the past three years, we’ve been collecting news stories about relocation and adaptation efforts. And here’s a feature, At home in a changing climate: strategies for adapting to sea level rise, on significant efforts towards adaptation.

Projects

Architects have, of course, brought ecological and sustainable thinking into their practices. Here are a few projects that stand out:

Stripped of cosmetics, but imbued with substance: inside the Berard Residence

Geotectura's ZeroHome turns waste into shelter

Student Works: This house made of trash teaches a lesson in green housekeeping

525 Golden Gate Seismically and Systematically Sustainable

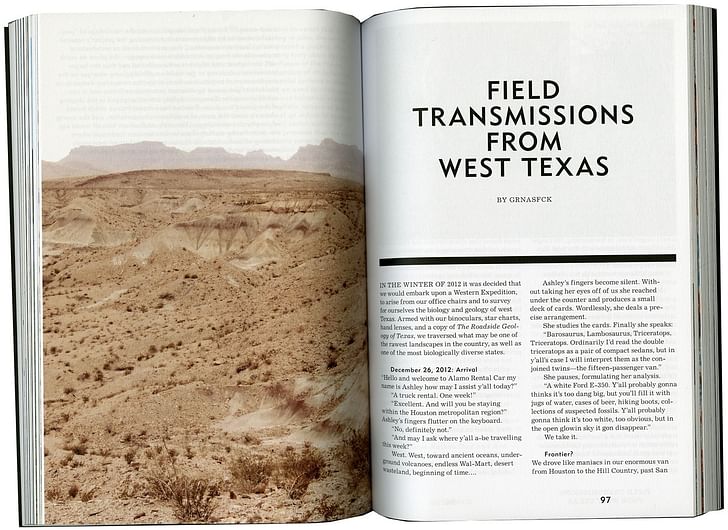

Other architects take more experimental approaches to understanding architecture’s role in a changing climate. Check out these interviews with exemplary practices DESIGN EARTH and GRNASFCK.

From elsewhere…

Archinect’s recurring series Screen/Print is an experiment in translating content from offline, online. We publish features from journals and books that we find exciting in order to expose them to a wider audience. Here are a few related directly to ecology:

Screen/Print #49: "Bracket" ponders how architecture should respond in extreme times

Screen/Print #12: The Cairo Review's "Future of the City"

Screen/Print #2: The Petropolis of Tomorrow

Want more still? Here are all the news posts tagged ‘global warming’, ‘ecology’, and ‘environment’.

*Nicaragua withdrew from the Paris Agreement because they didn’t think it was ambitious enough.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Good stuff all around. But, why no mention of landscape architecture? Seems like a glaring omission. The field's been leading the convergence of environmentalism and architecture for quite some time.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.