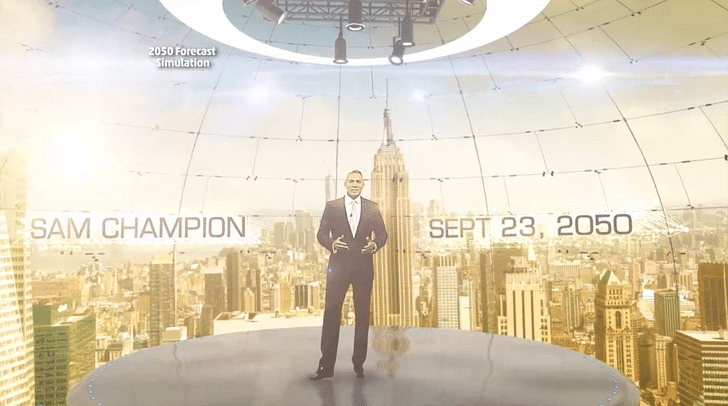

“Hurricane Kyle is tracking way off shore, but still Miami South Beach is underwater,” reports Sam Champion of the Weather Channel beneath a shifting, computer-generated dome. On the ground, storm tracker Jim Cantore, with the aid of a hovering drone, analyzes the surging tides that have inundated the coastal town despite the distance of the hurricane. In Chicago, a deadly heat wave forces the Cubs to play their games at night and in 90 degree weather. Meteorologist Stephanie Abrams documents cities endangered by the megadrought in the Southwest. “And it’s only going to get worse.”

Global warming disrupts normative temporality: actions in the far past bear down on the near future, like a ghost who promises to jump out at you, but won’t say when.

Besides being an innovative strategy for drawing attention to the conference, the videos also speak to the weirding of time produced by the ecological crisis. Human-induced climate change began with the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century yet we consider it a new issue. Perhaps more drastic in its implications for action (or the lack thereof), global warming is often perceived as something that is to-come, something that belongs to the future, instead of something happening now, affecting real lives and even ending them. One of the reasons for this is global warming disrupts normative temporality: actions in the far past bear down on the near future, like a ghost who promises to jump out at you, but won’t say when. Time is thoroughly out of joint.

This can be put another way.

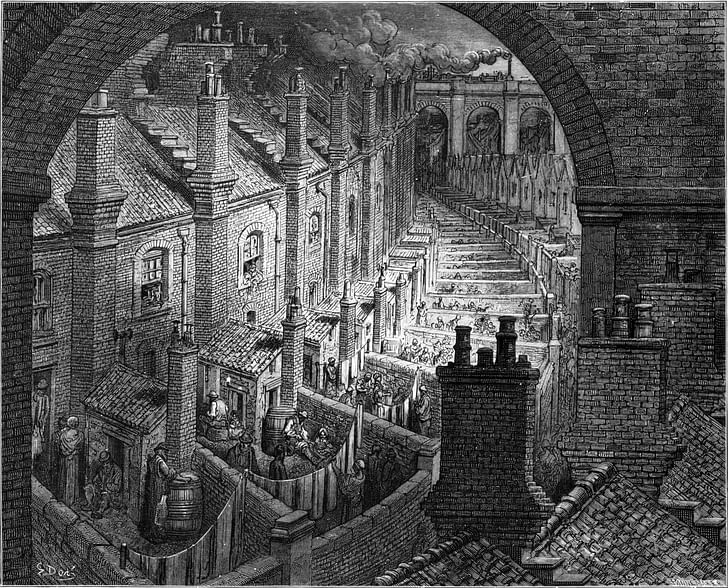

After decades in a legal office, a middle-aged man finally has enough money to purchase and build his dream home on an exclusive stretch of the California coast. An ecologically-minded individual, he installs solar panels on his bright copper roof and, as the construction workers install them, he imagines what they will look like once the roof has oxidized into a blue-green patina. In his expansive bathroom, he installs marble flown in from Carrara, Italy, but is careful to pay to offset the carbon footprint on terrapass.com. Above his water-efficient toilet, the man hammers a nail and hangs his favorite print: an engraving by Gustave Doré from his travels in London. He marvels at the perspective: the lines formed by the curvature of the bustling tenements stretch back to a locomotive and its long cloud of coal-fired smoke in the hazy distance.

Ten years later, as rising sea levels have washed away his beach and threaten the foundations of the house, he wonders whose folly produced this catastrophe. After all, it couldn’t possibly have been the construction of his house that brought the ocean up to his front door. Science doesn’t work that way, he reassures himself. But was it the imported Italian marble? Did the offsets not do enough? Or was it the exhaust from the truck that brought the solar panels from Arizona? Or was it farther back, the factory that his father managed before such things as carbon emissions were known? He packs up his things as he prepares to move; the cost of shoring up his house is prohibitive. He looks at the Doré print and is disturbed: perhaps he is living inside of the same thing that is depicted in the engraving. Perhaps those black clouds from the train never dissipated but instead circle around him now, closing in on him, choking him.

A city is an archive of memory containing the living traces of the past. A city allows me to imagine the past and project into the future.

To live in the present, as it were, is to live at the same time in the past. A direct line can be drawn from the very train that inspired Doré all the way to Hurricane Sandy two years ago and the devastation at Rockaway. We breathe air that is infused with a dangerously potent amount of carbon dioxide, some of which was emitted in the 19th century. On the other side, when I throw out a styrofoam cup it lands in the front yard of my great-great-grandchild. Bridging these times are the places where events occur, from the catastrophic to the banal. When I visit London, I can perceive, perhaps obliquely, the Industrial Revolution. One can still find walls stained with the soot of a factory that has been closed for centuries. A city is an archive of memory containing the living traces of the past. A city allows me to imagine the past and project into the future. This is the uncanny feeling that one has when one is in a ruin, or when one carves their name into a door. This is to say, the experience of architecture is quite like the experience of global warming: the present is repositioned into a larger context. When one designs a building, they do so with the hope that it will last; one imagines what people in the future will say of it once it has passed into architectural history. Likewise, as global warming becomes the defining context of our lives, we must renegotiate our relationship with both the past and the future.

Human interventions into geology have ramifications that will stretch into the future for longer than perhaps even our species will exist.

But the city also inscribes itself in another history: the geological record of the planet. This is true, at least, of cities since industrialization and after the so-called Great Acceleration of the 1950s. Cities literally make geology, and architecture is a geological force. The façade of the bottom two floors of a new high-rise is constructed with stone quarried from halfway around the world (i.e., Carrara, Italy). The cranes that assemble the building are powered by the liquefied remains of ancient fauna, drilled in the deserts of Qatar. The steel that serves as the building’s support originates in iron ore mined in Labrador. The hardwood floors installed in each unit were from the Brazilian Amazon, where deforestation has eroded massive quantities of soil, which, in turn, were re-deposited thousands of miles away by the river. The polystyrene foam used to insulate the building will take hundreds of years to biodegrade – long after the building has become rubble and all of its occupants have died. Such human interventions into geology have ramifications that will stretch into the future for longer than perhaps even our species will exist. For an increasing number of scientists, philosophers, and theorists, the period of time marked by human alteration of all processes of the Earth’s systems – from weather to geology – deserves an epochal name: the Anthropocene.

Even our own bodies are geologic.

The Anthropocene was first coined by Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen in 2002, who placed its starting point during the Industrial Revolution, which he considered a decisive-enough moment to serve as a breaking point with the preceding Holocene. For other scientists, this point dates farther back, to the beginnings of human agriculture that mark the geological record. Regardless, the Anthropocene thesis places humans in a strange position. On the one hand, the alterity of the species is marked by its profound influence, unparalleled by any nonhuman thing. On the other, the ability to maintain distinctions like nature/man becomes increasingly impossible as nature – normatively imagined as that which is untouched by, or at least exterior to, human activity – withdraws. Even our own bodies are revealed to be geologic; we chomp on calcium tablets and redeposit them elsewhere. Suddenly, everything becomes connected: when I build my house and consume massive quantities of fossil fuels it will effect my neighbor’s house – although perhaps a distant neighbor, in time or place. This is because the Anthropocene thesis necessarily implies that we all share an even larger house, which is to say, the planet. Moreover, that house is just as constructed, just as shaped, as any other work of architecture. We are finally catching up with language: oikos, the Greek word for home, is the root of ecology (oikos + logos = ecology, which is to say, the study of the house). As the philosopher and eco-critic Timothy Morton writes, “Home, oikos, is unstable. Who knows where it stops and starts?” (Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, 117)

Not only does a building sit on geology, but it is composed of geology and reorders geology.

The Anthropocene is increasingly entering the architect’s lexicon. This is unsurprising considering the degree to which architecture contributes to the symptoms of this new epoch, but also because architecture is perhaps the easiest entry towards thinking in the Anthropocene, towards understanding human activity as a geologic activity. The construction of buildings reshapes geology and sizably contributes to global warming and other defining phenomena of the Anthropocene. Architects, particularly landscape architects, have known for a long time the degree to which their practice physically shapes the ground, what it means to relocate granite and stack it to great heights. Not only does a building sit on geology, but it is composed of geology (ie. building materials) and reorders geology (ie. terracing). On another level, architecture can be understood as a synecdoche for the Anthropocene. It is both a contributing facet to human intervention on the geologic, but also refers, more generally, to the way that humans have become architects, in a sense, of the Earth’s systems.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is not only one of the oldest works of architecture ever constructed but it will also be among the longest to survive. We are closer in time to its construction (c. 2560–2540 BC) then to its likely erosion into unrecognizability (an estimated 1 million years from now), but, according to some estimates – such as that of the theoretical physicist Brandon Carter –, the Pyramids have already borne witness to a third of expected human existence. Between the laying of its capstone and its eventual disintegration, what has happened? Between today and then, what will?

Published last year by Open Humanities Press and available to download freely online, Architecture in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Design, Deep Time, Science and Philosophy gathers together a variety of interviews, essays, and projects with architects whose work is concerned with the Anthropocene thesis and its implications for architecture. It is a thought-provoking and accessible primer to thinking architecture in the Anthropocene, including writing and work by Seth Denizen, Eyal Weizman, Jane Wolff, Elizabeth Grosz, François Roche, Paulo Tavares and many others. Many of the essays and projects included in the book focus on the weirding of time produced when architecture is no longer thought in relation to the “style of its day” or in other periodistic tendencies, but rather geologically. In particular, many of the projects make use of speculative fiction. An old tradition in so-called paper architecture, such works provide a method to think towards the future, unburdened by the pragmatic necessities of the site.

Architects must choose to either continue contributing to the problem or instead to dedicate themselves to finding novel ways of adaptation.

While the Anthropocene cannot become another aggrandizing of the field, or fuel its megalomaniacal tendencies, we do not need to become paralyzed in the face of it. To quote Elizabeth Grosz, a preeminent philosopher whose work actively engages with both the Anthropocene thesis and more general considerations of spatial practice: “Architecture, in short, has the capacity to both extend man’s destruction of the environment, but also, at its best but much more rarely, it retains the capacity to invent new modes of co-existence, more sustainable ways of living and more aesthetic experiences of inhabitation.” As global warming, perhaps the defining characteristic of this new epoch, increasingly becomes felt in our daily lives, architects must choose to either continue contributing to the problem or instead to dedicate themselves to finding novel ways of adaptation. Over the next few months, this column will serve to highlight architectures in the Anthropocene that choose the latter. Moreover, it will explore ways in which the Anthropocene thesis changes notions of architecture and, reversely, ways in which architecture can help us understand what it means to live in the Anthropocene.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

3 Comments

I don't have anything to add, but I wanted to say I really enjoyed this article. Looking forward to part 2!

I agree with Evan. I learned something new and it had this 'post-internet' tone to it. Let's definitely have a few parts.

Great article, and an issue that becomes more prescient every day

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.