In case the name didn’t tip you off, let it be said that GRNASFCK is not your average landscape architecture studio. Whether producing disjointed travelogues in Celebration, Florida or organizing rallies for extremophile bacteria in San Francisco, GRNASFCK operates almost like an industrial dredge, unsettling easy or comfortable ideas about the relationship between architecture and ecology, and covering impressive conceptual (and geographic) ground.

GRNASFCK is the collaborative effort of Ian Quate and Colleen Tuite, both graduates of the Rhode Island School of Design’s Landscape Architecture program. Tuite, who has a background in studio art, turned to landscape architecture in the hopes that it could synthesize her interests in nature, technology, and radical activism. “I wasn't totally right, but I think architecture is a flexible platform to work from,” she tells me. Quate studied design and botany before a semester in the Galapagos, where he realized “it was better to pretend to be a scientist than to actually be one.”

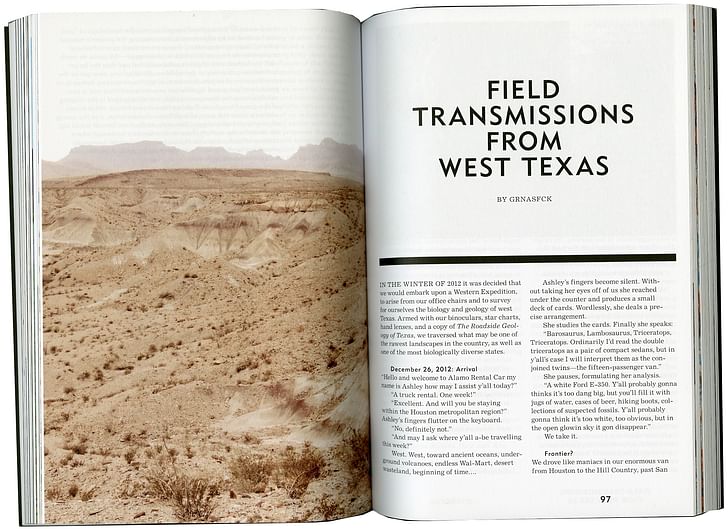

In 2012, GRNASFCK set off on a trip through West Texas armed with “binoculars, star charts, hand lenses, and a copy of The Roadside Geology of Texas.” The trip was documented in a wild, rambling text later published in an issue of MANIFEST: A Journal of American Architecture and Urbanism, an independent annual print publication dedicated to initiating a “critical conversation about the state of American architecture, its cities, and its hinterland.” Their journey begins at an exotic game park, the semi-accidental home for over sixty breeds of African mammals described as “less of a geographical perversion than a temporal reversion.” After all, before the Ice Age, the landscape that now comprises West Texas was “not unlike the African savannah, home to the large mega-fauna that characterized the Pleistocene epoch and that encouraged the hunter-gatherer to colonize the Americas.” Their journey continues, bringing them under the towering infrastructure of the “Wind Boom,” includes an accidental sojourn into Mexican territory, and culminates with one of them puking on a Donald Judd sculpture in the art-world outpost of Marfa, Texas.

At some point in “Field Transmissions from West Texas,” GRNASFCK asks, “What is the extended history of a place that is characterized by its blankness? What is the reality of geologic time for us, who have assigned ourselves the ridiculous title of ‘Landscape Architects’?” This seems to be one of the pivotal questions driving the work of Quate and Tuite. What is the reality of geologic time for us, who have assigned ourselves the ridiculous title of ‘Landscape Architects’? While taking on the name and guise of a landscape studio, they are constantly interrogating their own imperatives and preconceptions. Today, we are living in a strange temporality marked by a disjunct between the accelerated tempo of the everyday and an encroaching awareness of geological and climatological timescales. GRNASFCK takes this fissure as an opening, excavating, rather than covering-up, the apparent paradoxes and impasses that emerge as you stand outside during a camping trip gazing at “this vastness [that] you are projecting all of your critical theory upon, which has been deemed so fragile, has been underwater, exploded in the air, built up, and broken down.”

Quate and Tuite are currently in the planning stages for GRNASFCK’s next exploratory trip, this time to the Baaken Formation in North Dakota and Saskatchewan, the site of an ongoing fracking boom. Recently, we talked about their practice, the ecology of hangovers, and their interest in “earth-eating” operations, among other things.

I love the name of your studio – an expletive that, paradoxically, can only really be read. Can you tell me about the name and its/your relation to "green architecture" or "green-washing," more generally?

Ian proposed "Green As Fuck" for the title of our graduate thesis show at the school’s gallery; we had just spent three years being inundated with "green-ness" and we were sick of it. There is no post-industrial; corporate waste will provide landscape architects with materials to work with for the rest of time. "Green" is a slippery word – it conjures a narrative of ecological morality as an anecdote to the industrial era - a narrative we find false. There is no post-industrial; corporate waste will provide landscape architects with materials to work with for the rest of time. "Green As Fuck" was an attempt to subvert that tidy narrative, cleaning the slate of expectations and applying our tools of biological and architectural synthesis in provocative ways. We believe that is critical when engaging with the complicated and paradoxical techno-derivational landscapes that are redirecting open space today. The name was not approved for our show, but that inspired a sort of afterlife for the term that became our studio.

In general, your writing uses a lot of 'profanity.' I've a theory – and tell me if I'm completely off-base – that something more is going on behind this than ‘mere’ style. Paralleling the vowel-less expletive in your name, the use of profanity in your writing seems to speak to the emotional valences of the human subject in relation to the massive contexts that you two study. This is to say, there's a certain sense of anger/rage/horror voiced and then simultaneously rendered impotent or insignificant by the intrusion of an awareness of deep or geologic time scales. Can you speak to this a bit?

There's a mode of looking at the world right now, especially the natural world, the landscape, and saying, “We're pretty fucked.” Climate-petrochemical-induced extinction: the 20th century capitalist expansion of anglo industrial complex has connected parts of the world in unprecedented ways in it’s never ending demand for resources. As landscape architects and as human beings, we empathize with this reality and it is horrifying. But from a geologic perspective, industrial trauma to the environment is nothing more than a blip in a vast history that has nothing to do with people.

From a geologic perspective, industrial trauma to the environment is nothing more than a blip in a vast history that has nothing to do with people. What is more horrifying: that capital accumulation and corporate interests are poisoning the collective groundwater, or the awareness that our human struggles, pushing piles of dirt around, are ultimately meaningless on an indifferent, shapeshifting planet? In the words of John McPhee:

"Consider the Earth's history as the old measure of the English yard, the distance from the King's nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One stroke of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history." (Basin and Range, 1981)

The best we can do – what GRNASFCK wants to do – is understand these "earth-eating" operations (right now, for instance, we're really interested in hydrofracking): how they work, how they’re experienced on the ground, what their byproducts are, and how we can engage with these processes. The answers aren't clear, but we attempt to go beyond either saying "we're f-ed" or putting a greenroof on a oil refinery and calling it a day.

Also, swearing is fun; it's very human and relatable. Camping is mostly drinking beer, telling stories, and swearing. Maybe swearing is the most human intervention into nature.

You've written a series of "field transmissions" – as you title the first one – for MANIFEST. These are striking texts that move wildly from candid, profanity-laced travelogues to unsettling explorations of deep, geologic time. Before getting into them in detail, I'd like to hear about the basic approach/strategy behind them.

After graduating from RISD, we did a travelling studio with the Architectural Association Unknown Fields Division to Ukraine and Kazakhstan. The instructors, Liam Young and Kate Davies, were very enthusiastic and got us into some unbelievably bizarre and distant places – including the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, a true GRNASFCK landscape. Chernobyl is generally thought of as "most fucked place" – and for good reason – but it's also a really beautiful forest. After the meltdown, the trees captured the bulk of the radiation, Ideally, our writing acculturates geology. and to protect the forest from burning down it was flooded and restored to its native condition as a wetland. Now the zone has some of the highest biodiversity in Europe and is a major hub for migratory birds.

Anyways, experiencing that trip and the way it was conceptualized beforehand, which then played out and dictated the travel plans, was exciting to us. So the next year when an occasion (it happened to be Ian's birthday) rolled around, we decided to frame what would have been just another camping trip in Texas into something more exploratory – and we found an audience in the process. We lucked out working with MANIFEST because, although the editors are in academia, they encouraged us to spin this slightly insane narrative. We want to be in conversation with the academic world, but as a counterpoint.

Ideally, our writing acculturates geology.

In your writing, the "I" seems to be a temporary position, occupied indeterminately by you (Ian) or you (Colleen) and perhaps others. Can you talk about this?

The geologic scale can seem so unfathomable, but we experience it every day. To paraphrase Timothy Morton, when we touch our iPhones, We travel to places of material action, geologically leaky locations we're touching a platinum mine in Uganda; when we refill our gas tanks, we are touching the ocean floor in the Gulf of Mexico.

We travel to places of material action, geologically leaky locations, where the evidence of disturbance, but also creation, is evident. The organisms that colonize our landscape contextualize humanity in unexpected ways. While we see our narratives as a version of a field report, it seems important to acknowledge ourselves as emotional, human agents. In this way we are equally inspired by Hunter S. Thompson, John McPhee, and Chris Kraus. The "existing conditions" of the site include not just a survey the flora and fauna, but also being lost, being hungover, being scared, being awestruck.

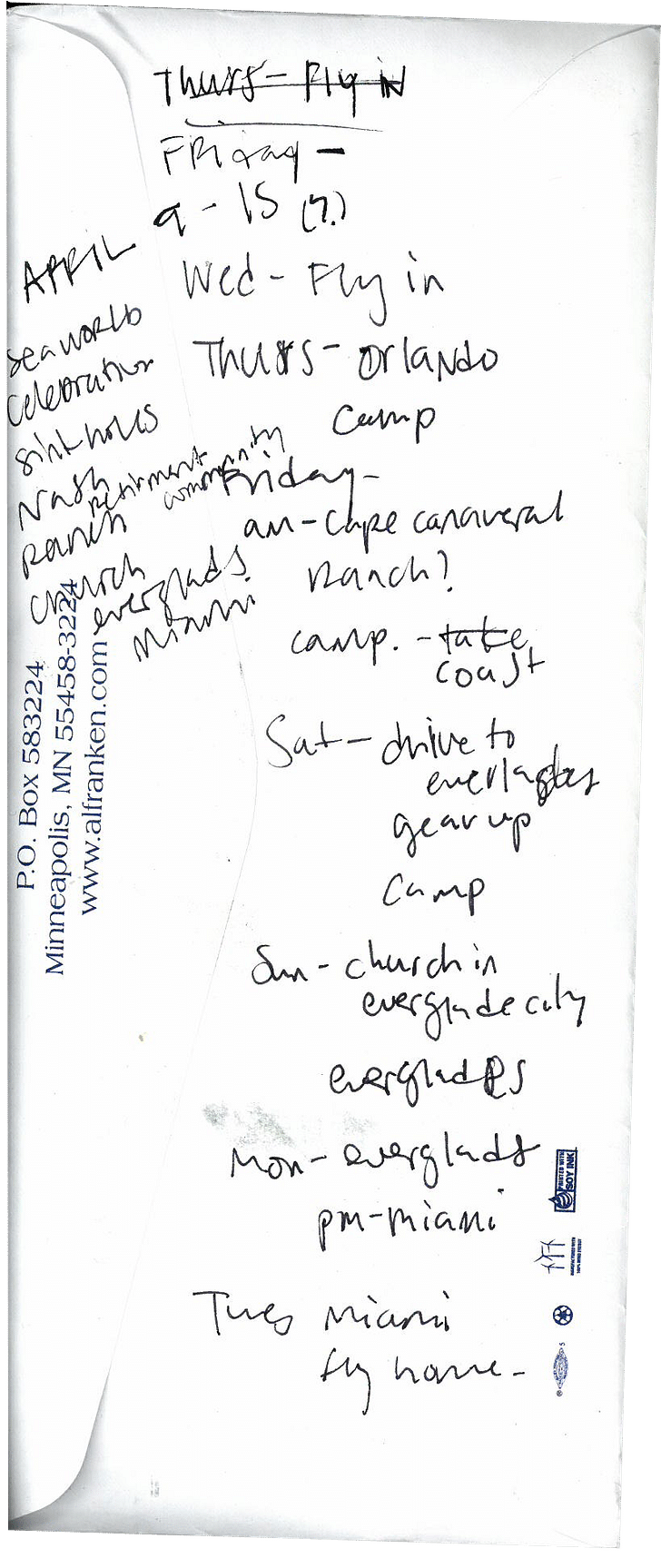

"Field Transmissions from West Texas" documents your trip into some pretty surreal landscapes. Likewise, in the soon-to-be-published "Sunshine Eschatology," you're tripping around Florida, camping amidst wild pigs in saw palmetto savannahs, talking to an angsty teen in Celebration, Florida, and finally traversing to a mega-church-cum-nightclub in Miami. I'd love to hear the background behind these essays: how you picked your destinations, the relation between truth/fiction, and how the writing process occurs – collaboratively or otherwise.

More generally, I'm fascinated by the unique manner in which GRNASFCK decodes these complex landscapes. What’s the broader imperative behind your work and the manner in which it is conducted?

We explore greenness beyond a surface treatment. We want to see how geologic and cultural forces touch down and express themselves through plants and animals.

We go to places that are unexplored by our field, and where landscape and culture have an isolated expression. We have solid research periods before we select locations to travel – sending each other Google Earth screenshots and news and journal articles, etc. We want to take a core sample but we'll do some dowsing too. We're looking for a diversity of geographies and cultures, but we always have inclinations of where we want to go. Then once we dig in to a place, there is a whole world from the bedrock up.

In terms of our writing process, we'll hash a rough structure together and then pass a draft back and forth. We try to plan our trips around building a narrative, rather than the narrative being an afterthought. Furthermore we make certain pains to connect with friends of friends (of friends) when we travel, to be enveloped in a genuine, and consequently unpredictable culture. And while the authentic experience of a place generates a narrative that cannot be invented, we're less concerned with "reporting facts" than what the mise-en-scene of a place can tell us. We want to take a core sample but we'll do some dowsing too.

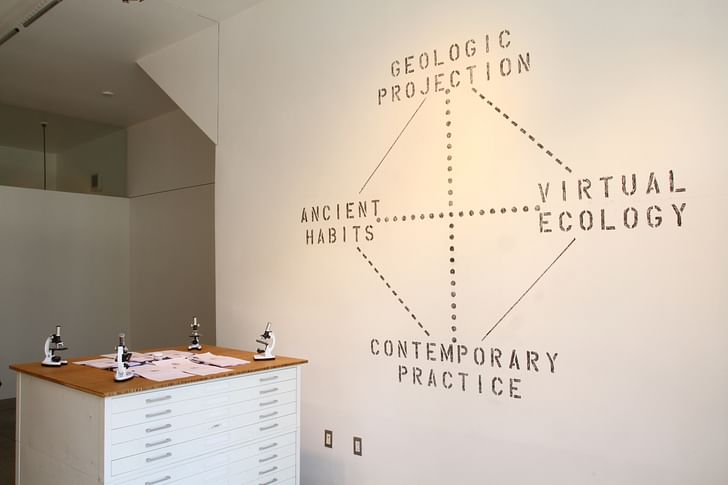

So last fall we met under the auspices of your exhibition at the StoreFrontLab in San Francisco. "I Love Extremophiles!" included a rally for elements of "invisible urbanism" and a panel (disclaimer note: I participated in the panel). Can you talk about the terms that were at play, in particular "invisible urbanism"? And about the exhibit and panel, in general: how you chose the speakers, the discussions that were intended and those that came about in actuality?

Post-industrial and brownfield sites are somewhat fetishized in landscape architecture; there's this brown-to-green narrative where we roll a park over the material excess of the late 20th century (capped with thousands of yards of concrete) and congratulate ourselves for restoring "natural order”.

We're more interested in understanding what these sites have to offer as human manipulated landscapes. On a micro-scale they are host to new forms of ecology – heavy metal eating bacteria and plants which are evolving in response to these new habitats. As our cities and bodies become increasingly fused with biology and technology, it makes sense to look to these coping strategies of ancient life, namely, extremophile bacteria. As our cities and bodies become increasingly fused with biology and technology, it makes sense to look to these coping strategies of ancient life, namely, extremophile bacteria. Extremophiles, because of their ability to metabolize materials such as petroleum and natural gas, are currently being domesticated for resource extraction (and subsequent cleanup) by the mining and gas industries. But within the urban environment, they remain feral and unstudied.

San Francisco is a great place to explore these ideas, given its arc from shipping and military base to tech u/dystopia. The curators at StoreFrontLab, Arianne Gelardin and Jacob Palmer, were incredibly supportive, and also interested in exploring the fringes of architecture.

The Summit on Invisible Urbanism was part of our larger installation, I Love Extremophiles! and was a somewhat informal conversation on the many scales of engagement with contaminated urban landscapes. It's important to us to sample from a diverse pool. It's safe to say that every event we host will include architects, landscape architects, scientists, planners, technologists, and artists. But honestly, we were so damn nervous we don't really remember what everyone talked about, however, Bay Area landscape architect David Fletcher dropped a great line about "collaborating with catastrophe,” so yeah that was the main take away.

Note: Documentation from “I Love Extremophiles!” will be included in the forthcoming issue of lunch, a journal published by the University of Virginia School of Architecture.

Do you have any thoughts regarding the current state of architecture and landscape architecture, more generally? Where do you stand on the relationship between what we could call architectural thinking and architecture-as-building, with the understanding that the building sector has what could be called a majority stake in climate change?

We see speculative and built work as fraternal twins - different expressions of a shared genetic code, and of equal importance. Internally, the field is expanding into many exciting directions reflecting an optimism of what can be brought together through provocative design thinking. However, there seems to be a hesitancy to insert these radical ideas into practice, which in turn creates a lag in public perception of the capabilities of the field, directing what kind of projects are brought in front of landscape architects. At the same time, to be honest, its industry (agriculture, hydrofracking, mountaintop removal, oil refining) and not so much design that is currently the major driver of landscape morphology. How we reconcile the human scale with the industrial is a huge challenge. Our approach is to look closely at industry, and try to understand how its effects ripple down to the ground, biologically and culturally.

[Landscape architecture has] a unique attribute to our field that is all but absent in every other design discipline save biological engineering: we use living materials as our medium.

Regarding climate change, ultimately the ecological question becomes less how to build around it, and more about how to contain it. Industrial human activity essentially acts as volcanos, extracting stored energy from the earth and circulating it into the atmosphere. So when people talk about “another extinction event”, that’s true. The question becomes how to contain it, how to scrub it. We think you start with plants. Actually, we think you start with bacteria, which we’ll call digital plants. This will have to be, by necessity, an industrial scale operation.

In the meantime, where landscape architecture can come into play is creating more equitable human conditions on the ground. The burden of climate change falls on underprivileged populations. We’re starting to see climate refugees in the arctic, which will only expand with time. Architecture can potentially intervene by both bio-fortifying existing cities and communities, and working to create a welcoming and resilient infrastructure in urban centers.

Climate change is forcing us to reimagine how we live on our planet; this is huge opportunity for landscape architecture to respond in kind. We have a unique attribute to our field that is all but absent in every other design discipline save biological engineering: we use living materials as our medium.

I know you're planning a trip for this summer – will you produce another article for MANIFEST?

This July we will be travelling to the Bakken Formation in North Dakota and Saskatchewan, tracking the oil boom and the resulting new ecologies and economies. From all accounts thus far, it's a really wild situation, so we're excited to see for ourselves what's going on.

An apartment in Williston, ND rents for more than in NYC.

It's been known for decades that the Bakken shale is loaded with gas, but the current systems of drilling were not capable of extracting it efficiently – until the adoption of hydrofracking, in the early 2000s. Now what was ranchland is incredibly valuable. Halliburton, et al. has moved in, and the population has exploded with people (mostly men) travelling to the Bakken for work, at a huge impact on local community and culture (#rockinthebakken). Housing is largely unavailable, and what exists is extremely expensive – an apartment in Williston, ND rents for more than in NYC. There are endless video tutorials on Youtube on how to live out of your truck. Now there are barracks-style "man camps" being constructed, as well as luxury condos, so this overnight (and temporal, who knows how long the boom will last if it hasn't peaked already) urbanism for a largely precarious and transitory working class is a phenomenon that architects need to be looking at.

The ecology is clearly also in massive flux, on a surface level from the boom in people and infrastructure and drilling over a mile into the earth! But we suspect it's happening on a microscale too; the fluid used in hydrofracking contains biocide, and what we've learned from our extremophile research is that when a toxin is introduced, a lot of things are going to die, but a few creatures will thrive. The soothing sounds of geologic scale industry lubricated with "hydrocarbon corpse juice” Ian's been working with molecular biologists at Cornell Medical School on a project documenting bacteria in the Gowanus Canal (a Superfund site in Brooklyn), and we’ll be swabbing drill pads and hopefully core material to analyze what's going on a microbial scale.

We'd like to make this trip into a cross-disciplinary research expedition – potential collaborators, please get in touch! We will be doing another piece for MANIFEST, and we foresee this trip generating a few more projects as well. One idea we're kicking around is to make hydrofracking field recordings and mix them into a GRNASFCK concept album/meditation record – the soothing sounds of geologic scale industry lubricated with "hydrocarbon corpse juice,” as [Reza] Negarestani refers to petroleum…

“Sunshine Eschatology” will be out later this spring in MANIFEST 02: Kingdoms of God.

Finally, what are you two reading? What tabs do you have open?

Hito Steyerl. Hyperobjects by Timothy Morton. Summer of Hate by Chris Kraus. The Northeastern Driller. Reza Negerastani's Cyclonopedia. Donna Haraway. Youtube videos about Williston, ND. The Boom by Russel Gold. Hydrofracking by Alex Prud'homme. Ganges Water Machine by Anthony Acciavatti. Objectivity by Peter Gallison and Lorraine Daston. DIS Magazine’s “Disaster” issue. And a Derrida PDF on “biodegradables” has been haunting my browser for about two months now...

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Ian, I believe you helped me build this in my backyard? (see photos) pretty sure you sketched it in 5 minutes...

I am pretty sure that was you, I def. remember your websites and the Foreclosed project on your website....say 3 years ago...we surveyed a project for I-Beam Design way out on Long Island....?

Great firm name! and great fuckin' shit here!

"The best we can do – what GRNASFCK wants to do – is understand these "earth-eating" operations..."

Keep it up!

/\ the part of the tree with the mushroom that killed it covered in stain and epoxy, after 3 years fungi won....tree eatin'

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.