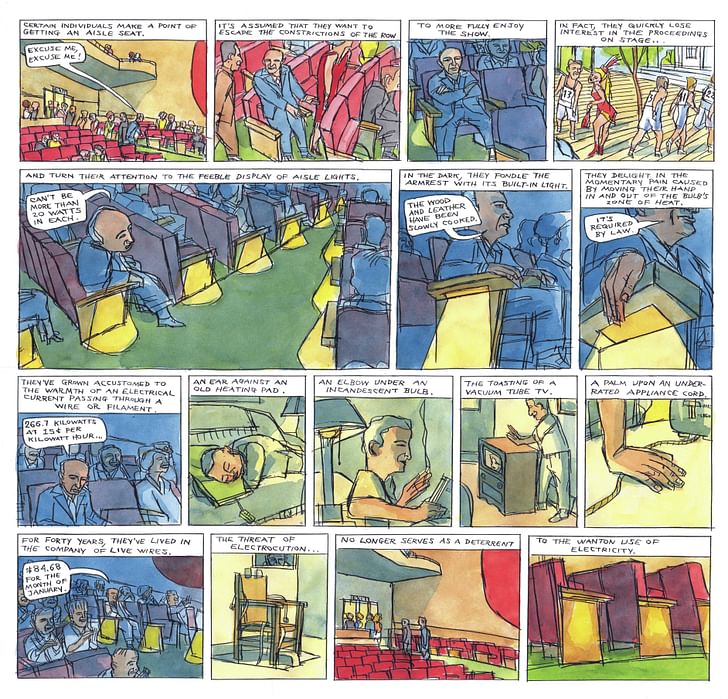

Architecture is one of the most expansive fields there is: it bridges the loftiest conceptual realm with nuts-and-bolts physicality. Some architects never leave the paper world, while others dwell primarily in crowded conference rooms and muddy building sites. This is partially why the comic strip of work Ben Katchor is so remarkable; it acts not only as an idiosyncratic survey of the built world, but as a humorous exploration of the conceptual one.

Consider any of Ben Katchor’s collections, from Julius Knipl: Real Estate Photographer to Hand Drying in America and it’s easy to get lost not only in Katchor’s nuanced humor, but in his unusual appreciation for structure as character. I think if you grew up in a city, you associate nature with either parks or cemeteriesObscure basements and diners and apartments conceived for insomniacs play as great a role in the strips as any of the human characters. In fact, aside from Julius Knipl himself, Katchor rarely has reoccuring organic characters: the strips are mainly meant to function as one-off tales about urban places and incidents. They are the experience of the city from a perspective that is neither traditionally schooled in architecture nor adverse to dreaming; and for this reason, they capture something about the built environment, and our lives in it, that is exquisite.

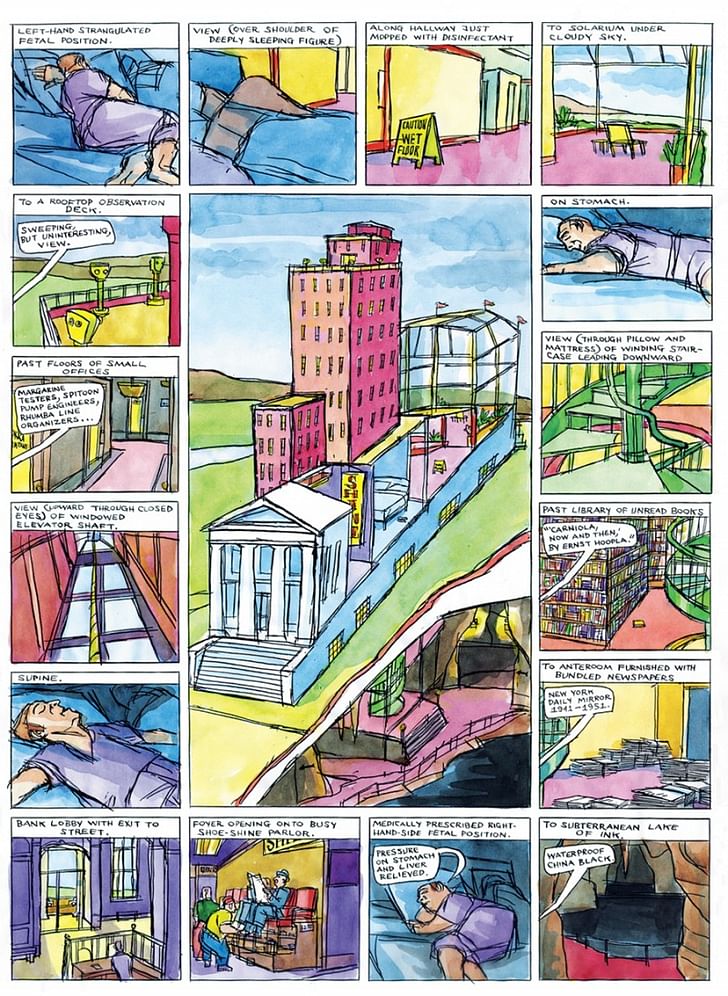

“The strips are kind of written in a half-dream state,” Ben tells me over the phone. “I’m not fully asleep when I’m writing them, but I’m somewhere in between. A lot of them have this free-associative kind of quality as when I’m in a dream, but then I’m awake and I can edit them, make them coherent in some way.”it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that over the course of his career Katchor has drawn entire cities

Ben was born and raised in New York, the son of a Jewish Polish socialist who immigrated to the United States just before World War II. His father encouraged him to pursue his drawings, even if he was somewhat cynical about the notion of "careers" in general. Ben explains that he didn’t grow up in any architectural masterpieces, but rather in crummy, ordinary 19th century speculative apartment buildings. I suggest that growing up in this environment may have sharpened his critical skills, or at least his wonder in observation.

“I was always looking at buildings, from the basements and the rooftops and places some people didn’t look around too much. I grew up in New York, always in a building, some architectural or urban space,” he says. Writing about anything other than the built environment, as when he attempted a strip about agriculture, has always proved somewhat challenging. Although he occasionally visits the countryside for a change, nature itself as a setting is problematic. “I think if you grew up in a city, you associate nature with either parks or cemeteries. So a kind of morbid feeling comes over me in the country sometimes. It’s strange. I mean, I’ve gardened a little bit. I think if you’ve figured out how to use nature, it would make sense. I’m not deeply involved with agriculture.” They just scream about how much money is involved in their erection

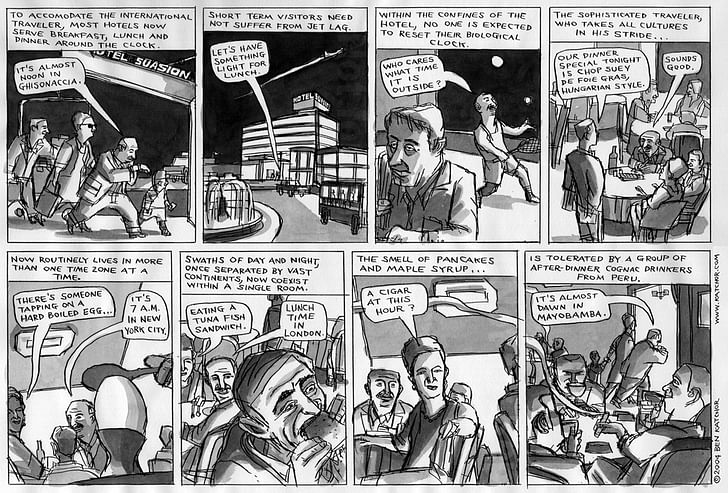

In a strip from Julius Knipl: Real Estate Photographer, Ben explores the concept of the global hotel, a place where travelers can exist in a semi-modernist, time-zone-free lodging that puts them into a kind of hospitality limbo. It’s funny as a concept on its own, but the detail and consideration that goes into the idiosyncratic design of the hotel, as well as individual details like the lighting fixtures within that imaginary space, is typical of Katchor’s work. Although the strips are intentionally accessible to a general audience, architects can also enjoy the individuality of each setting, the care and detail that goes into creating that particular atmosphere. Conceptually, it wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to say that over the course of his career Katchor has drawn entire cities, from mixed-use structures to residential properties to the landscape architecture of public spaces. The buildings aren’t necessarily flashy, but they aren’t all dismal efficiency apartments, either. Every strip seems to feature a carefully imagined, signature space. Reading Katchor’s work is an escape to an urbanity that is both familiar yet unique.

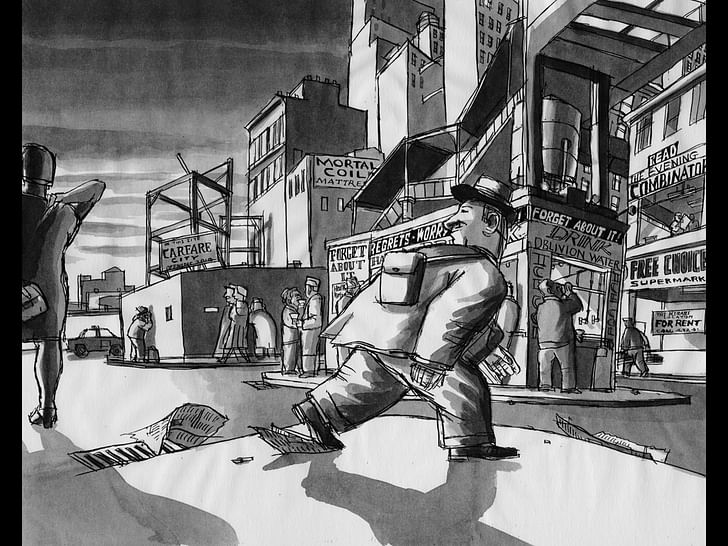

Naturally, this makes me curious about what Ben thinks about contemporary architecture. He sighs, and admits that he is not deeply impressed, primarily because so many new projects, especially those in New York City, seem to rarely take into account the community who will live with them. “They just scream about how much money is involved in their erection,” he says. “Architecture needs real estate, and that whole meeting of architecture and real estate is the ultimate showing off. You put this gigantic thing up in the street. You could appreciate it on a piece of paper if it was that great. A lot of architecture feels like, you know, the money could be used for a better purpose.” Every story has a spatial drama to it

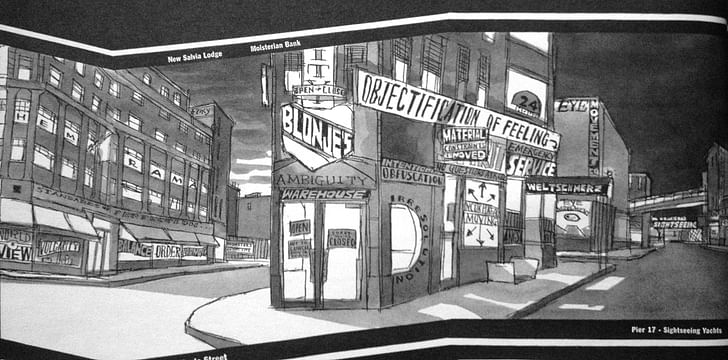

In some panels, Katchor allows the surrounds, such as the signage, even the way space itself is partitioned within a building, to tell the story of a place and a time. A panel featuring a store sited on the median between two intersecting boulevards is titled “Objectification of Feeling,” and features an elliptical window promising “Intentional Obfuscation.” "Irresolution" curves its way around the window in bold, quasi-Art Deco lettering. It’s a reading of the world that, while fictional, seems to convey a far more accurate truth.

“Every story has a spatial drama to it,” Katchor says. “There’s a drama about a rooftop. The place and the spatial drama becomes evident right away. That’s how comic strips work, otherwise if I didn’t have an interest in that kind of spatial description, I'd write prose. If you make regular comics, they’re usually pretty boring comics, at least to me. I draw what I want in a comic strip: you know, there’s more than just talking heads or something. It’s an imagined physical world.”

To mark the 25th anniversary of the publication of Ben's first graphic novel, he has been gaining increasing recognition across a variety of different mediums. His comic "The Carbon Copy Building," in which dual buildings that were mirror opposites of each other in terms of the types of businesses and occupants they contained, was staged as a musical with performers by Bang on a Can. In the architectural realm, Katchor’s work appeared for years in the back pages of Metropolis Magazine. He is self-effacing about it. “I did this strip in Metropolis for many years, I guess some architects read it. I don’t know who exactly read it. Interior designers, interior decorators? I think it had some trade audience. I don’t know what these people made of my strip.”

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

4 Comments

Thank you, Ben Katchor, and Archinect.

Really enjoyed reading Julius Knipl Real Estate Photographer in late 80's LA Weekly, or was it the Reader? For me, Ben Katchor 's morbidness capture sort of mild dystopic experience of the eveyday city. I am glad this is now what architects reading and learning from. "Objectification of feeling" all the way, these are very full strips indeed. Thanks for putting it on Julia, and sending Ben Katchor a big appreciation for his work. Here is someone for Archinect podcast.

Before this piece I had never heard of Ben Katchor, but back in March, Fran Lebowitz listed him (along with others like Toni Morrison and Junot Diaz) in response to the question "Which writers — novelists, playwrights, critics, journalists, poets — working today do you admire most"

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.