In advance of the 2016 Venice Biennale, we've spoken with the curators behind a few select pavilions to check in on the status of their exhibitions. For this feature, we share our conversation with Cynthia Davidson and Monica Ponce de Leon of the American Pavilion, "The Architectural Imagination".

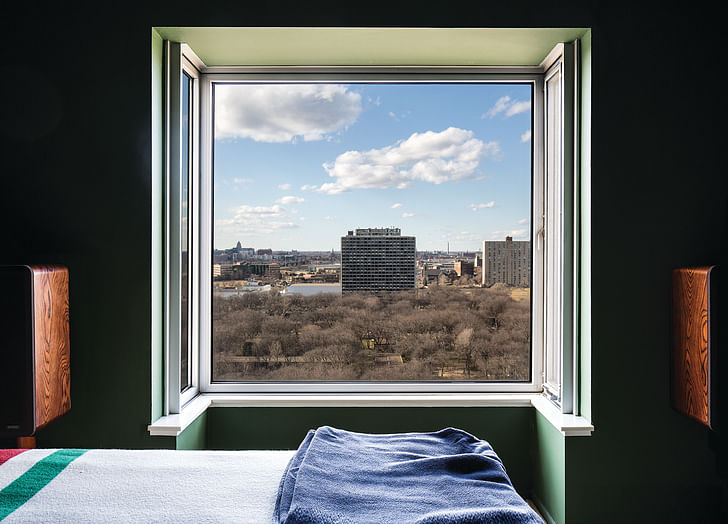

With a name like “The Architectural Imagination,” it’s not surprising that the exhibition for the American pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale will focus on speculative projects. But what makes these speculations most interesting, according to curators Cynthia Davidson of Log Magazine and Monica Ponce de Leon, the recently-appointed Dean of Architecture at Princeton, is their relationship to the actuality of their sites in Detroit.

The curators enlisted an advisory board of city officials, scholars, and community leaders to assist the twelve selected teams (which included practitioners from across the country), in becoming intimately acquainted with the Rust Belt capital. And, according to the curators’ stated intentions, the speculations won’t be merely hot air circulating Venice, but rather are intended to have a life after the show in their city of origin.

In total, the roster of participants includes the three West Coast-based firms of Greg Lynn FORM, Pita & Bloom, and Zago Architecture (all based in Los Angeles). The southern United States is represented by Present Future from Houston and Mack Scogin Merrill Elam Architects from Atlanta; while Preston Scott Cohen Inc. hail from Cambridge, Massachusetts and MOS Architects and Stan Allen Architect from New York. The practices representing the Midwest are Marshall Brown Projects and Bair Baillet from Chicago (the latter also is based in Columbus, OH) as well as T+E+A+M for Ann Arbor, Michigan. A(n) Office is the only Detroit-based practice in the group.

I talked with Davidson and Ponce de Leon to find out more about their conceptual strategy, the curation process, and their response to criticism from local activist group Detroit Resists.

To begin, could you tell us a bit about the theme, “The Architectural Imagination”, as well as your decision to focus on speculative architecture rather than, say, existing built work?

Cynthia Davidson: We wanted to do speculative projects because we wanted to bring architecture to the table in Detroit and in post-industrial cities. Most people think that architecture is only buildings, they don't understand that architecture is also ideas, that buildings represent ideas.

So to do speculative projects that have no developers and aren't meant to be built is really about the ideas that architecture brings to the table and these ideas have forms, because you have to represent them in models, in drawings, videos, whatever [...] Imagination was a way to bring another level of conversation to Detroit and in a way that might be a model for other post-industrial cities. That's why they're not specific projects for Detroit, I think.

A speculative project is arguably more real than projects that merely register and thus reinforce the limitations of the present.Monica Ponce de Leon: You know there’s an urban historian at the University of Michigan, his name is Robert Fishman, and during a lecture [he gave] on Detroit, he was asked a question [about] why is architecture important, and why are projects for Detroit important. I thought his answer was really beautiful and – I'm going to paraphrase but – he talked about how [speculative projects] make visible what otherwise [are] understood as hidden possibilities. A speculative project is arguably more real than projects that merely register and thus reinforce the limitations of the present.

I thought that was a really beautiful way to address the capacity of architecture to pose alternatives to the status quo, to pose alternatives to the present. There has been a lot of work on Detroit and on the post-industrial city that has been led by developers, that has been led by interest groups, that has been led by government entities. And our intent was to look at possibilities that took all of these forces into account, but was not driven by these forces, and instead could be driven by ideas of the possibilities of each of these sites that could be more inclusive than the limitations of a particular interest group, or a particular economic interest on a particular site.

I'm interested in how, specifically, those forces are taken into account in the exhibition. ‘Speculation’ can have multiple meanings and there’s another side to it with a violent history in the city. For example, the image of Detroit often seems preeminent to the actuality in the collective American imaginary (if such a monolithic thing could be said to exist). And also, of course, there’s the role of speculative finance in the housing bubble and then the 2007 crash.

How do these other modes of speculation figure into the exhibit? Do they? What’s the position of ‘the real’ of Detroit in these speculations of the city?

MPL: We did something that I think is unique for an exhibition in that we developed an advisory board of different people in Detroit that are dealing with issues on the city and have been dealing with issues on the city for a long time, but all of them with different points of view and all of them with a different background. From heads of nonprofits, to academics, to neighborhood leaders, to the head of the city planning office in Detroit. And they helped us select the four sites.

We wanted the reality of Detroit and not a single version of the reality of Detroit.But also they helped us connect the architects with different neighborhoods and community organizations with different business-owner groups, with the owners of the site. So while the projects are speculative, they're very much rooted in the reality of Detroit. We wanted the reality of Detroit and not a single version of the reality of Detroit. Not the version that dominates the media. But multiple versions of the reality of Detroit to be the background for the work of the architects.

Cynthia, you were mentioning that, at the same time, the projects aren't necessarily specific to Detroit. What do you mean by that?

CD: Well they're very specific to the sites in Detroit, but what I mean by that is that the ideas that are inherent in each project are ideas that could be applied in other, similar post-industrial spaces. Other abandoned factories, other abandoned waterfronts, etc. I mean these projects are very specific to these four sites, but these four sites are not just typical of Detroit, they're typical of other cities that were heavy, heavy industry cities. Northern European cities. Many North American cities. That are dealing with empty factories and declining population. And that's what I mean by they have broader applications.

It seems like there's going to be a pretty wide variety of speculations, projects, and visions of the possibilities or futures of Detroit. Are there commonalities uniting the twelve projects?

CD: One of the things that happened was all the architects went to Detroit, they all spent time on their sites, they all met with people, the advisory board and other members of the community. [...] Because we wanted them to have programmatic aspects to their project, they aren't fantasy projects, they're not just formal projects. They all had to write a program for their formal architectural proposal. What's interesting is they came up with very different programs and very different forms. There's three architects on each site, we have three very different proposals for each site. And yet, across the twelve architecture teams, twelve very different proposals.[The participants] all focused their architectural imagination on everyday life.

If there's a commonality between them, I think it's that all of them have somehow understood that Detroit has been a divided city, that segregation is part of its history. And in these forms, at least I read, a new – I call it a new porosity – but a new lack of barriers. That symbolically, or metaphorically, what these projects may have in common is a permeability to anyone. There's no inside or outside or division.

That doesn't make sense unless you see them [laughs].

MPL: The other thing that they have in common is that there is an emphasis, even though they all look very very different, there is an emphasis on the everyday. Nobody did a museum. Nobody did an art center. They all did programs that are more embedded on the everyday. And that, to me, is very interesting. They all focused their architectural imagination on everyday life.

CD: Like houses, schools, industry – that kind of thing.

It's a pretty varied group of architecture practices that you selected, as well. How did that selection process go? What were you looking for?

CD: We did a nationwide call for expressions of interest. We got over 250 responses and when Monica and I looked at these we really wanted to reflect the range of responses, not just take the cream off the top of the milk, so to speak. We wanted to look more broadly at the diversity of practices that are working in the United States, the sort of diversity of the American population, and that meant both generationally, ethnically, gender – everything. And that's, I think, what motivated our choices, but also we were looking for creative visionaries practices and that was first and foremost. But then to really reflect this diversity was something we were really excited about.

MPL: We were really excited to have teams from the West Coast, the South, Midwest, the East. We have really a lot of geographic diversity as well as, as Cynthia pointed out, architects that have very different backgrounds and therefore very different ways of approaching design.

CD: The truth is, we really wanted to get twelve different projects. We're not surprised that we have twelve very different projects.

MPL: That was intentional.

CD: It was very intentional. We didn't want to get, you know, twelve religious facilities that all sort of looked the same, shall we say.

Twelve megachurches?

CD: Right. Or we didn't want to get twelve gas stations, twelve factories, whatever.

MPL: Or twelve museums [laughs].

CD: Yeah [laughs] we didn't want that.

Some time after you announced the curatorial theme, a group called Detroit Resists published a statement that expressed trepidation about the exhibition. They write, "We are curious to see the relationships that emerge between the speculative architectural projects produced by the U.S. Pavilion’s visionary architects and the urban catastrophe that many of Detroit’s residents are currently attempting to survive. We fear, however, that the U.S. Pavilion, precisely as an attempt to advocate ‘the power of architecture,’ is structurally unable to engage this catastrophe and will thereby collaborate in the ongoing destruction of the city.”

What's your reaction to this statement and to their anxieties?

MPL: I think, having been in Detroit for a long, long time, I think this is a very, very narrow perspective of Detroit. And a very stereotypical picture of Detroit. One of the reasons that I was personally interested in having Detroit be the subject of “the Architectural Imagination” at the American Pavilion at the Venice Biennale is because there is so much more to Detroit than the images that dominate the media.

There is so much on-the-ground invention today taking place. New forms of occupation of space. New social organizations. New ways to come together as communities and take charge of daily lives. And I think that those can serve as models for other cities abroad and I think that those can really catalyze the 21st century city. For example, the kind of grassroots activism that generated Eastern Market. The kind of partnerships that led to the Riverfront Conservatory and the transformation of the riverfront [...] The kind of community organizations that are keeping areas of Detroit really robust and thriving, like Mexican Town. These are lessons that we think can really provide [the roots] for new architectural and spatial ideas.

So, for me, the position that takes the view that, well, the general public will not be able to engage in a larger conversation about the physical reality of the city is a really narrow way of looking at Detroit. [...]

People want to believe there's a better future and this is part of that.CD: I want to address, directly, what you said, that Detroit Resists fears we're going to "collaborate in the ongoing destruction of the city." This project is so much about starting new conversations and bringing projects to these neighborhoods and communities and to raise the level of conversation about options for Detroit going forward. There are a lot of exciting projects that are actually being built, that are happening in midtown. City Hall is working very hard with some of these community groups to stabilize neighborhoods.

The exhibition is going to go from Venice to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit. There's a whole other level that developed in the course of our work with the advisory board that got people in Detroit so excited that they're going to be on an international stage like the Biennale, that they wanted the show back in Detroit. And they're going to use that show at MOCAD next February and March to bring conversations into communities that are ignored when it comes to "what do they think about design," "what do they think should happen".

And there are so many real life concerns in Detroit, like water supply and fire service and all these other things. People want to believe there's a better future and this is part of that.

Does that "change the image of Detroit" for people who see the show in Venice? I don't know. I don't think that was my ambition. My ambition in this was to raise the level of discussion about potential projects, programs, whatever, for Detroit by talking about it in communities in a new way.

MPL: In a way that is not historically what has happened in Detroit, where the conversations about public space and development [are] always tied to the economic interests of a particular group.

CD: Right, and we are independent of all of those interests.

Can you tell us a bit of what to expect from the upcoming edition of Log?

CD: Well, Log is the "CATA-Log." We get to play with our name [laughs] and it is a catalogue. It documents – there are ten or twelve pages on each of the twelve teams with a statement by the architects and drawings and photographs... Robert Fishman, who Monica already mentioned, has an essay about Detroit in the mid-twentieth century, which is a fabulous essay [...] And Maurice Cox, the city planning director, has a long interview of conversations he had with Monica and me about what he's trying to do through city hall, working with neighborhoods and stabilizing the population. And then several architecture theorists and historians have essays about what is the architectural imagination.

It's sort of a two-pronged show. The project is about and for and on – and every other possible preposition – of Detroit, but it's also about the power of imagination and the specific architectural imagination, and its ability to stimulate the public or collective imagination.

This interview is part of Archinect's special May 2016 theme, Help. Do you have socially-oriented projects of your own? Submit to our open call before May 22.

The U.S. Department of State selected the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning to organize the U.S. Pavilion exhibition. Cynthia Davidson and Monica Ponce de Leon are the pavilion co-curators. For more information on the images from the "My Detroit Postcard Project," visit this link.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

2 Comments

Nice pictures but hasn't the theme of urban blight in Detroit been exhausted? What more is there to learn? Detroit is fucked up? No shit. Let me guess the proposals...adding green spaces, pod houses, farmers markets, abandoned factories as museums...ow how about graffiti museums for the blacks!...etc. At what point are architects just exploiting race, poverty, and urban blight? The fetish is only possible from the outside...when you can go home to somewhere else...like its the difference of a bondage fetish vs real torture .

How about either doing something to help the area or leaving it alone...the constant emphasis on its demise only perpetuates the stigmas that scare people away. There is no shortage of ideas on how to "fix" Detroit with architecture. There is a shortage of actions taken.

What's next, AIA sponsored ghetto tours?

Detroit is so 2012. cmon elites, find a new city to exploit!

Actually I'd like to see a follow up on all of those vanity foundation grants of millions of dollars in the name of Detroit. See where all that money went.... Probably not anywhere near the ground there.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.