How the creator of SimCity turns reality into playground.

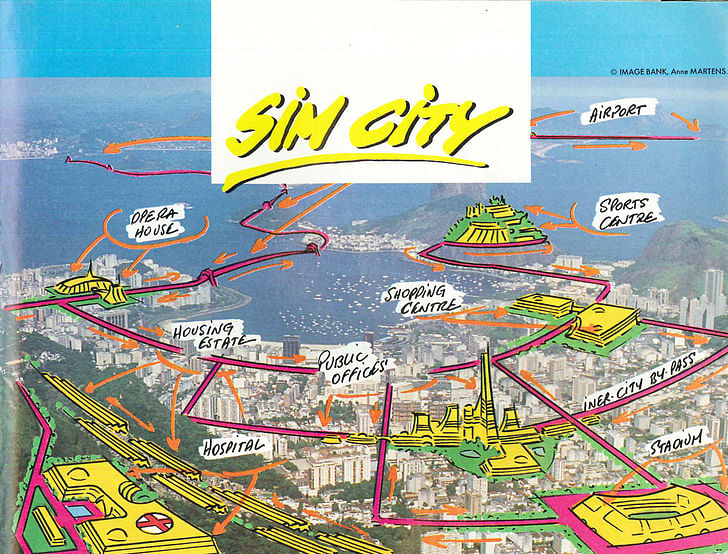

I have never played a single game in the Sim universe, but I still grew up in Will Wright's universe. SimCity, Wright's 1989 creation, was one of the first "software toy" games, with no explicit villains, heroes, goals or narratives, just an interactive system to be tweaked and let grow. A game like SimCity takes an idea of high-resolution complexity, such as an urban space, and breaks it down into a series of knobs and levers that anyone can engage with – from the grade schooler with minimal English skills to the professional urban designer. Gamer or not, one can regard SimCity less as a competition and more as a living model. Simulations are a way to virtually carry out iterative design principles with the click of a mouse, foregoing hours of cutting and CAD-ing to create working analogies to real life. I marvel at SimCity not because it represents reality, but for its potential to elaborate on reality, and show how invisible mechanisms in our own world might work.

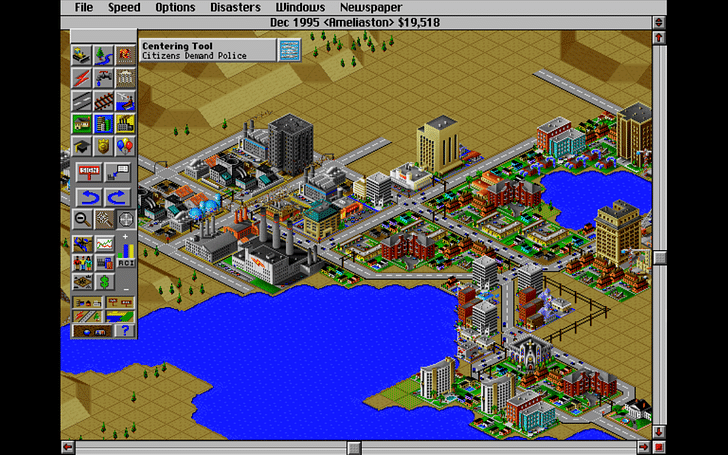

Will Wright addressed the crowd at ACADIA 2014 conference as an architect, as a game designer, and most emphatically, as a futurist. Wright studied architecture in college, along with mechanical engineering and robotics, and conceived of SimCity as a way to actively engage with the theoretical urbanism of Jay Forrester (the founder of Systems Dynamics). The timing of SimCity's release in 1989 puts it at the first strong surge in commercial personal computing technology. Beforehand, most PC games were adapted from the arcade, where graphics played a simple, secondary role. But by the end of the '80s, personal computing had become more common and its gaming market had exploded, with graphics quickly enriching as CDs replaced floppy disks (remember those!?) for their superior storage capacity. Wright's games, which include the Sims canon as well as Spore, have grown with personal computing's capacities into incredibly visually rich and complex environments, getting closer and closer to the approximate reality.

Wright imagined a future where not only do we better understand how urban systems work, but those systems better understand how we work.Wright's brand of futurism, as addressed in his keynote, isn't a political or ideological dream necessarily, but one where virtual and real worlds are mutually beneficial spaces – for all societal levels. In the spirit of the conference, Wright's "software toys" make gamers (read: anyone) into their own agents of creativity; as they choose to play the game, and design the reality of an active city, they exert their agency within the logic of a system and get to see its effects play out. Stimulus and result are quickly learned, and experimentation leads to better understanding of how systems are structured.

Dropping references to Kevin Lynch's "Image of the City" and Christopher Alexander's "A Pattern Language" (which inspired The Sims), Wright imagined a future where not only do we better understand how urban systems work, but those systems better understand how we work. Glimpses of this are already apparent with things like "smart homes" and adaptive environments, where the idea of a "designed" object or space isn’t limited to a temporal or physical stasis. The time between science fiction’s future and the present is quickly collapsing: hoverboards and self-driving cars now exist, and Tricorders (aka smartphones) are already in nearly a billion people's pockets worldwide*.

This vision of urban sensibility is set on making anyone capable of understanding analog urban environments, sharpening consciousness of systems that are easily taken for granted. But in all likelihood, those in the ACADIA audience already know these systems pretty intimately. What good is a sandbox if you have to stay inside of it? It may be impossible to predict how these interlocking systems of interactivity will come to bear on the built environment ten, twenty, or fifty years into the future, but practicing architects would do well to acknowledge the freedom games like Wright’s afford designers. By now, the generation that grew up with SimCity (and may not even remember a pre-internet world) is in architecture It shouldn't be hand vs. CAD, but CAD extending the hand's reach.school, and while they may never be sure exactly how, their urban sensibilities have already been irrevocably impacted because of that. The game's reality and the built reality are in constant dialogue, complete with hidden biases and presumptions of what a city should or shouldn't be.

While Wright is not a practicing architect, he's at the center of ACADIA's mission: understanding the computer's impact on design. Today, it's almost redundant to speak of "computer-aided design", but when ACADIA was formed in the early 1980s it was still an alternative practice. Wright reminded the audience that treating computers as a separate accessory of design fails to acknowledge that feedback loop and dialogue between computer and human: “These things we used to treat as toys and games now are intersecting our real world, and are having as much to do with it as anything else.” It shouldn't be hand vs. CAD, but CAD extending the hand's reach. Staking a flag on the side of human or machine misses the point – they are, from this point on, in each other's camps.

Despite clearly being in line with ACADIA’s ideology, Wright didn’t draw much of a crowd. The ballroom at USC’s campus was only about half full at the start of his lecture, the first keynote of the conference. Perhaps this was simply a matter of celebrity: Wright is no Hadi-va, and his talk was more academic than the other keynotes, which focused on showcasing and explaining individual work. Rather than surveying every Sim franchise and his battling robots, Wright’s talk was almost a exegesis; a perspective to understand the world based on abstract cybernetic principles and a healthy dose of technological-determinism. Anyone, not just architects or urban planners, can acclimate to this outlook through games like Wright’s – sandboxes that allow individuals to be agents of their own surroundings, rather than passive consumers.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

6 Comments

I was obsessed with simcity at one time. Never realized Will Wright studied architecture - it would be interesting to hear an interview with him about his views on contemporary urbanism and theory.

"It shouldn't be hand vs. CAD, but CAD extending the hand's reach."

man, I needed this qoute like a week ago ;) I am going to have to re-evaluate Christopher Alexander's "A Pattern Language" now, where can I find more on how SimCity was based on this book?

@midlander, in this interview Will Wright gave to ICON, he says

"I’m actually very interested in architecture as a field because it’s one of the few fields where they study design as a process separate from the artefact that they construct. So they study how houses and buildings work, but they also study how different design processes within architecture have played out"

He also answers a question about whether user-interactivity – has any applications in architecture...

Also, I do wonder, whether talk of techno-determinism and "market dynamics" means he is perhaps more in the camp of the Smart City crowd? Or more of a "user-generated" utopian, a believer in DIY based experimentation?

Thanks Nam, interesting read. I liked this quote:

What we’ve found universally is that when players make something, and the more unique it is to themselves, they tend to attach a lot of empathy to it, they really care about it, even if it doesn’t work that great compared to something that a professional has designed, the fact that they have made it makes all the difference to them.

From the ICON interview it seemed pretty clear to me he looks at technology as a way to effect more responsive user control of the products they consume. He was talking about gaming, but I'd expect he has a similar lazzie-faire approach to the built environment. The opposite of someone like Wright who saw the home as a perfectly-designed space handed down from above for the occupant to deal with.

That's a notion I agree with. I've always enjoyed walking around ordinary suburban neighborhoods, observing how people customize their cookie-cutter homes. It's actually a beautiful adaptation and expression of life which too many architects try to design out of existence.

Terrific article. Loved the "Wright is no Hadi-va"

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.