Entering an architecture competition is basically a form of speculative investment. Time is money, and competitions tend to require a lot of both. Models, renders, and prints—not to mention wages—can deplete the coffer quickly, especially for a young practice. A studio will invest their time and money in an entry in the hope that, at a later date, it will generate a return: a commission or some recognition. Unfortunately, competitions tend to be risky investments.

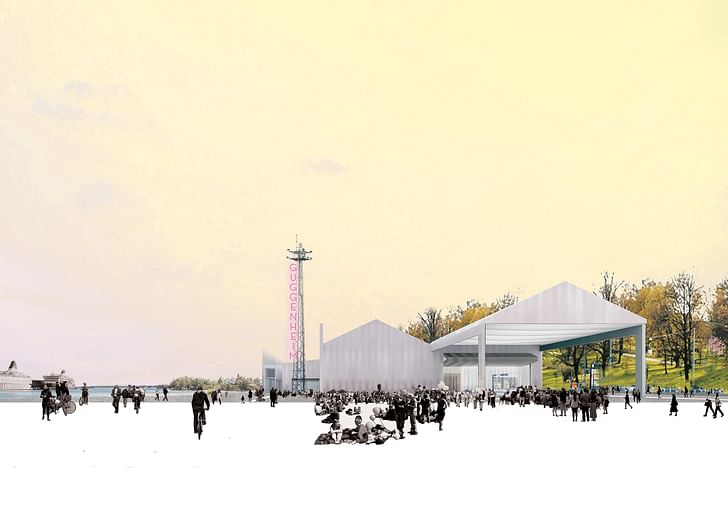

You have a 46.36% chance of winning at blackjack. The odds of winning the Guggenheim Helsinki competition? About .06%. Of course, the comparison doesn’t really hold. The rules of blackjack are set, while architecture competitions are subject to opaque procedures, inherent biases, and jurors’ tastes. “There are many competitions that claim to be fair but, in many cases, they always choose projects from experienced architecture firms,” state Escobedo Solíz, the winners of this year’s Young Architects Program at MoMA PS1. “Others, don’t allow young firms to participate.”

According to an extensive report by the Van Alen Institute in collaboration with Architectural Record, 57% of architects polled stated that the “opportunity to experiment, work more creatively than in typical projects”, motivated their decision to submit. A further 54% stated that they were compelled by an interesting issue (respondents could select up to three answers). On the other hand, architects’ “key limitations” were, by far, a “lack of compensation for time/resources” (78.6%), followed by a “low probability of winning”.

In other words, creativity will cost you. But sometimes, competitions do pay off. After all, not all competitions are won by big firms, even if a lot of them are. Importantly, not all architecture competitions are the same. And they’re one of the few ways of putting your work out there for people to see. Often an architecture competition gains the firm attention, even if they don’t win.A competition entry can be a rhetorical device, an opportunity for a studio to declare its intentions. One of the most shining examples of this would be the Parc de la Villette, one of the last times that a losing entry gained almost as much attention as the winner. While Bernard Tschumi’s design won out in the end, Rem Koolhaas’ entry helped launch his, and OMA’s, career. A competition entry can be a rhetorical device, an opportunity for a studio to declare its intentions.

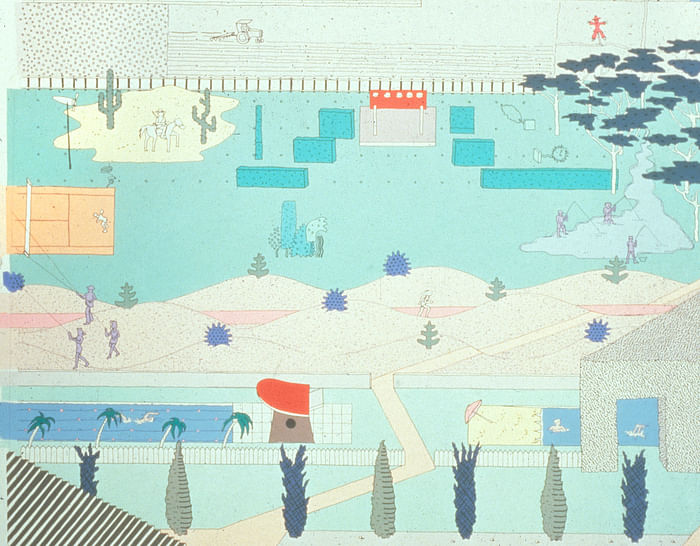

For Escobedo Solíz, this involved showcasing their interest in pre-existing material, both conceptual and physical. In their presentation, they heavily cited their sources—the site specific work of Robert Smithson and other artists—and designed their proposal around the existing features of the MoMA PS1 courtyard. “We really like to point out our sources of inspiration because we don’t believe that ideas comes from out of nowhere,” they told me over email.

Parasite 2.0, a Milan-based studio founded by Stefano Colombo, Eugenio Cosentino and Luca Marullo, actually won a competition by criticizing the culture of competitions. According to their proposal for the Young Architects Program | MAXXI, the larger socioeconomic structures conditioning the field of architecture have turned architects into “competition machines that only produce numerous projects each year, only good for filling the Dezeen or Archdaily databases, without any proactive contribution to the issues that today should be urgently investigated.”competition machines that only produce numerous projects each year, only good for filling the Dezeen or Archdaily databases

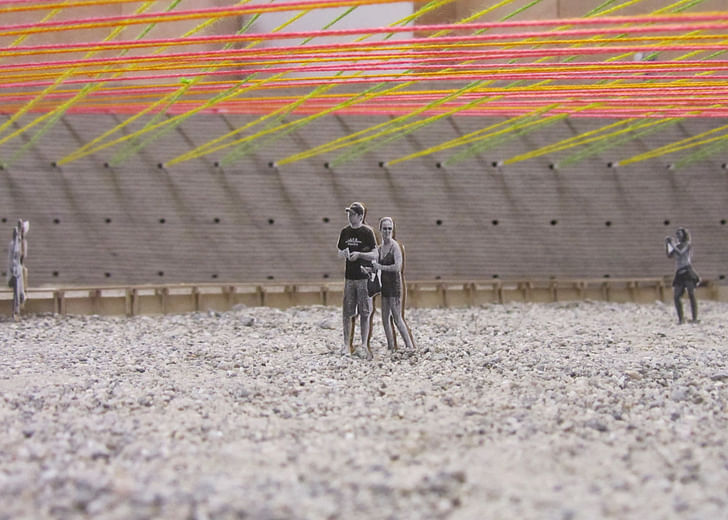

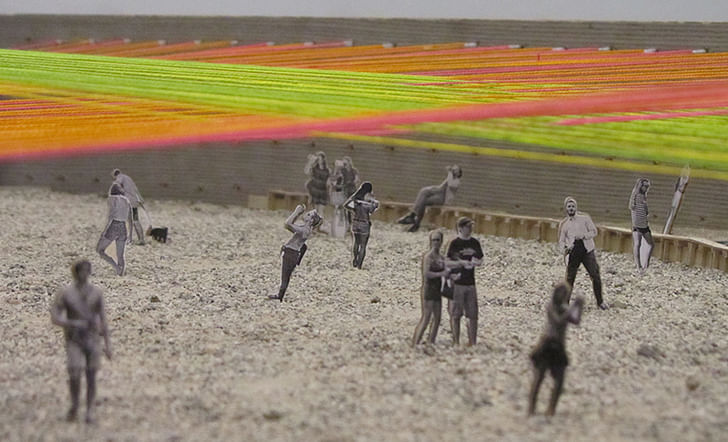

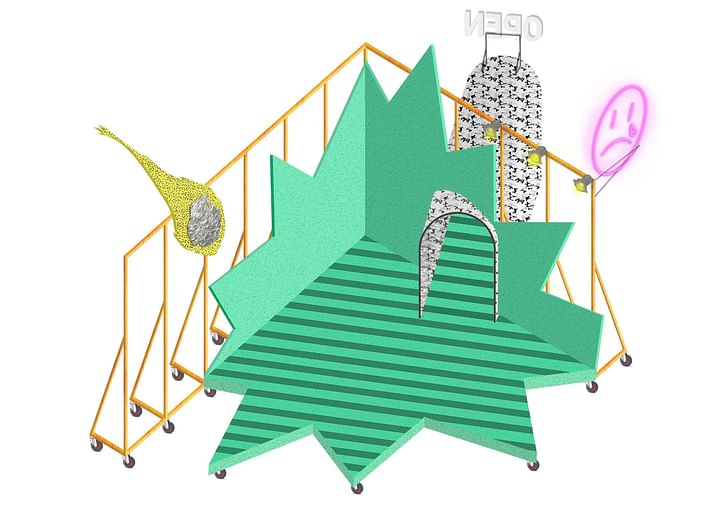

Many architecture competitions these days are for temporary pavilions—the Serpentine Pavilion, or the YAP, for example—and, according to Parasite 2.0, this isn’t just a “waste of economical resources”, it’s also producing “Instagram Architecture,” or work that’s designed mainly to be photographed and posted. So, for their submission, they turned this logic upside down, producing a pavilion that served as infrastructure for a “temporary school” with rigorous programming. The pavilion, which looked quite a bit like a stage set, was filled with distilled signifiers of our contemporary “age of anxiety”. Equipped with green screens, visitors could still satiate their desire for a selfie (with an augmented reality background), but that wasn’t the entirety of the project.

“Sincerely, the project was not developed to win,” Parasite 2.0 told me. “It tried instead to highlight provocatively some of the contradictions of this competition. The proposal, in opposition to the ‘Instagram-friendly architecture’ typical of temporary pavilions,Competitions are a game of resource-allocation and careful selection. left the physical installation in the background, thus presenting a complex curatorial program with the aim of transforming the museum into a place of debate.”

“For us, [architecture competitions] are a place in which you actually set up conversations,” Urtzi Grau of FAKE Industries Architectural Agonism, finalists in the Guggenheim Helsinki competition, tells me over the phone. In the past, FAKE has been a finalist in the PS1 Young Architects Program, and recently won a competition to build a new velodrome for the city of Medellín, in addition to many other competitions. Despite not winning every one they enter, Grau insists, “We are great believers in competitions.”

As their name suggests, FAKE Industries Architectural Agonism are proponents of agonism, a political theory that accepts a place for certain forms of conflict as positive and constructive. You can counterpose agonism with antagonism, Grau states. “Antagonistic ideas are two sets of ideas that require the destruction of the other in order to survive or to win... while agonistic relationships build up on productive disagreements,” he says. ”Instead of having an enemy you have a kind of adversary, and an adversary is someone you disagree with but at the same time the disagreement allows you to construct and build up your position."

But for a competition to serve as an agonistic forum, it’s necessary to identify who are the figures you are engaging with in the first place. In most cases, that’s the jury. Rather than characterizing as negative the exclusivity of a jury, Grau insists that a jury of learned experts in architecture is exactly with whom architects should be conversing. That way a discourse can actually develop. Grau also believes that competitions can be a way to engage with a public. “Maybe only an architectural public,” he notes, “but a public nevertheless.”A competition entry is not just a solution... It is almost a manifesto.

FAKE Industries Architectural Agonism stress that they’re careful about which competitions they enter, to ensure that they don’t drain all their resources. They also assert that while architecture competitions often get a bad rap, they’re not all that different from the type of competition that happens in any business for a commission or a client. Competitions are a game of resource-allocation and careful selection. But, if done correctly, they can launch your career.

"A competition entry is not just a solution,” Grau states. “It is almost a manifesto.”

This feature is part of Archinect's special editorial focus on Games for August 2016. Click here for related pieces.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

The Van Halen Institute?!?! Rock on!!!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.