In late May of 2012, my friends and I travelled up to Montreal from upstate New York for the first time, only vaguely aware of the escalating student demonstrations there. When we arrived, we found ourselves in a sea of red. The students we stayed with all had little red felt squares pinned to their shirts and gave us some. Their apartment overflowed with red pamphlets and posters. Plastered beneath overpasses and on bus stops, Paris ’68-inspired silk-screened posters – some by the collective École de la Montagne Rouge – served as a backdrop for the massive daily protests that shut down major arteries and overpasses. Students in the streets and their parents on porches loudly banged pots and pans, a chaotic orchestra playing the deafening casserole. It felt as if there was not a single square inch of the city that was not red: even the lights of traffic signals took on a revolutionary hue.

The students were protesting a planned gradual tuition raise of over one thousand dollars. As the movement increased in pitch, it expanded into a more general strike as labor groups became involved. Through the use of these strong visual and auditory tactics, the so-called “Maple Spring” was able to grow and maintain momentum despite even the passing of the draconian Bill 78, an emergency law that restricted demonstrations and forcibly kept the universities open. After the government announced a tuition freeze in September, the students finally returned to class.

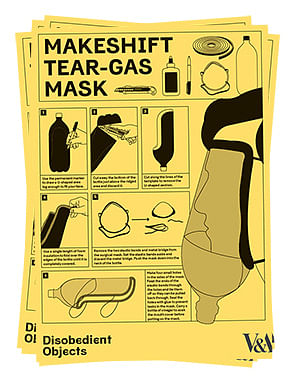

A red felt square is one of many objects included in the ongoing “Disobedient Objects” exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Tapestries, inflatable structures, videogames, dollar bills, bicycles, how-to guides, painted trucks, book-cover shields, street signs, and puppets are on display in an effort to showcase “how political activism drives a wealth of design ingenuity and collective creativity that defy standard definitions of art and design.” Focusing on objects made since the late 1970s, the show contains objects that straddle the line between utility and aesthetic punch, with an apparent emphasis on the use of symbolism in resistant disruption. The timeframe seems particularly apt considering the increasing theatricality of protest movements since Paris May 1968, such as the advocation of “carnivalesque revolution” by the magazine AdBusters, one of the early fomenters of Occupy Wall Street.

That the exhibition website has an entire section obliquely dedicated to defending the show’s institutional context evidences the unease inherent in a museum – certainly an apparatus of authority – displaying “anti-authority” objects. Generally, the show seems less oriented around traditional “resistant objects” – ie. guns, Molotov cocktails, pavestones – but rather around objects that self-consciously appropriate techniques of visual art. Concordant with the temporal focus of the show, the theorist Boris Groys discusses what he considers a uniquely new phenomenon of “art activism” in the most recent edition of e-flux. This is not the critical art of the last few decades: instead of “merely” criticizing institutions, particularly the art system and the general conditions underlying it, art activism seeks to “change these conditions by means of art... in reality itself.”

Groys scrutinizes the post-Walter Benjaminian and post-Guy Debordian line of thought that rejects the “spectacularization” and “aestheticization” of protest. Instead, while he contends that “we are living in a time of total aestheticization,” he asserts that that does not necessarily preclude potentials for action. He distinguishes the political function of design and art, contending the former wants to change reality while the latter accepts reality as it is, but condemns it as “dysfunctional,” as “already failed.” According to Groys’ dissection, many of the objects displayed in “Disobedient Object” would fall into the category of design, of tools or equipment used to directly intervene into the fabric of reality.

For Groys, the political history of modern art begins with the founding of the Louvre as a museum by the French Revolutionary government. He contends that while prior class struggles tended to be followed by waves of iconoclasm against the symbolic objects of the ancien regime, during the French Revolution, those symbols were literally turned into museums and art, aestheticizing them and thereby divesting them of power. For Groys, this lays the foundations for the emergence of modern art practices and discourses. He writes that “since the French Revolution, art has been understood as the defunctionalized and publicly exhibited corpse of the past.” The museum serves as a sort-of graveyard for the status quo, “to aestheticize the present means to turn it into the dead past.”

Here is the thin line that the exhibit straddles: since the objects on display were intended to influence reality, what happens when they are exhibited in an institutional context? Potentially, they are robbed of their use-value as they become aestheticized. Does this aestheticization totally reduce them to political insignificance? Maybe not: the dissemination of how-to pamphlets and other material could expand their potential reiteration. That being said, my more cynical side tends to think that the objects will become diffused into the world more through the gift shop and its grenade-shaped planters than in fomenting new protest movements. After all, the Victoria and Albert Museum is funded by the same state apparatus that led to mass punitive retribution after the 2012 London riots.

“Disobedient Objects” is currently on exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. More information is available here: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/disobedient-objects/

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.