I'm hoping that some of you might be able to help me out with a current studio conundrum. Sometimes I like to beg for free advice without doing any real research, too! (just kidding - I hit "search.")

Do any of you know of particularly notable projects that address accessibility successfully/interestingly - whether or not they are actually ADA-compliant, and whether or not accessibility was a design objective or simply a result of some other conceptual/formal process.

I just posted about this in my school blog & I'm thinking of things like

OMA's McCormick Center at IIT,

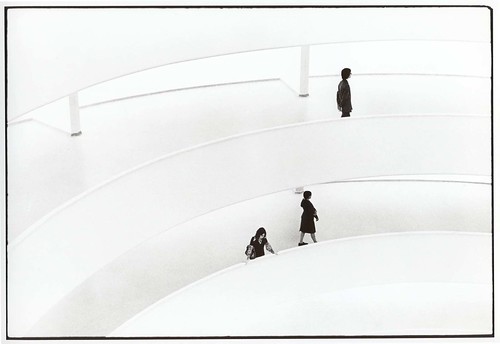

FLW's Guggenheim Museum in NYC

H&DM's Mercedes Benz Museum

...and the like.

There are a few typical ways to address accessibility to people with mobility difficulty (I'm barely even dealing with, for example, blindness right now). Lifts, elevators, ramps, or putting things all on one floor.

So I'm faced with this issue: I'm being pushed (by both my critic and myself) to develop an "interesting" section for a multilevel studio space. A non-pancake-stack-with-elevators section. Intuitively, it seems that lots of level changes might not be the most ideal way to go about designing, if one's goal is to have a disability-positive building (as opposed to one that is jimmy-rigged into accessibility) but I also certainly don't think that designing for disability precludes this kind of variety, if done well. I'd like to know of a few more precedents Is there anything I haven't thought of yet/don't know about? Anything flamingly awesome? I barely even know how to talk about this!

from your examples, it sounds like you are simply interested in any building with a ramp of which there are obviously many. you may find it more interesting and challenging to take on disability specifically rather than a post-rationalized architectural response to disability. i don't know if that is helpful or not.

susanS, great thread. i am curious though, how would you as an architect design for a physically challenged athlete? say one of the Murder Ball guys? it seems that given the obvious - we are all different, i could think of a situation where many athletes with physical challenges would welcome a "hostile" environment or rough terrain.

there was some competition years ago, i think it was a 'house for a blind person' or something .. one submittal was basically a series of 3' corridors so the blind person would be able to feel their way around. my memory is sketchy but the plan had all these thick walls,used poche, and focused on surface textures as opposed to space.

then a year or two ago there was a t.v. show on one of those channels (hgtv? discovery channel?) with a blind guy who worked as a consultant when designers were working on spaces for the blind. i gotta start writing this stuff down i'm starting to lose it ..

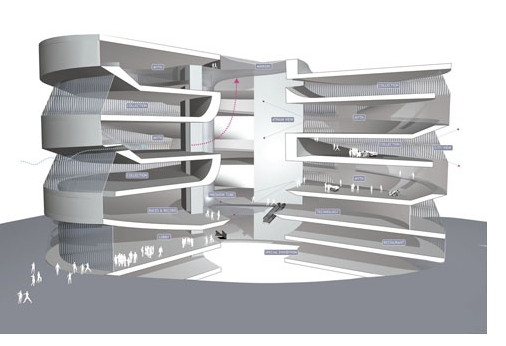

this is a rec center on a public park specifically designed to accommodate people with physical disabilities. not that it serves them exclusively - the client's goal is to be fully open and to make the place desirable enough that anyone/everyone will want to participate together. see: http://www.themvpzone.org/

the design challenge we took on: to make everything as much as possible about 'access'. for us that meant:

- setting the building down into the landscape so that everyone could come right out from grade onto each level (incl the roof terrace) to look over the landscape,

- suppress any stairs in favor of ramping or elevator,

- make the volume as open as possible so that it could be comprehensible from anywhere inside

- etc - basically anything we could think of that pushed the idea of 'access' at any program or activity area.

program includes aquatic center, golf/pro shop (artificial turf @ tees and greens), courts (including those designed for wheelchair rugby aka murderball), track, multipurpose room (tennis, indoor soccer), dance/movement space, computer rooms...

this one: http://www.flickr.com/photos/archintentlouisville/sets/72157602875699075/

...

...was a landing for a steamboat. designed to get people down a 40' bluff to the dock level, then to accommodate as much as 20' of rise and fall of the river. boarding could happen at any of the four levels, depending on water elevation, during sailing season. a funicular brings people down to the top level and then ramps connect each tier.

I used the terms ADA, Accessible, and Universal Design, because they all mean slightly different things.

jafidler - "ramp buildings" qua "ramp buildings" are certainly not my only interest. (Something that does interest - or rather annoy - me, however, is the designation of "ramp buildings" as a specific kind of architecture, especially when connoted pejoratively with trendiness - maybe I'm reading more into your comment than I should though.) I'm not sure what you mean by "you may find it more interesting and challenging to take on disability specifically rather than a post-rationalized architectural response to disability." I am trying to avoid a way of thinking that would be described as "post-rationalized." I don't think it would be more interesting to focus on "disability" broadly rather than architectural considerations of disability. There is a whole body of scholarship/research/theory/activism devoted to disability, and that oeuvre is way, way beyond my scope right now. From the small amount of research and conversation I have had with researchers & activists in the area, it appears that many people WANT architects to put more effort into addressing disability with architecture. Since I am working on an architectural design assignment, I actually consider architectural responses to disability to be the most interesting approach.I personally tend toward really simple/pared-down solutions to things, so gradual transitions of grade (ramps) or eliminating # of floors are first-line appealing, as opposed to 37 level changes with a mechanical lift at each skip, or handing every user of my building a jet-pack upon crossing the threshhold. (No, wait, relying on jet-packs to make my building accessible is actually AWESOME.) That said - I want my building to be as accessible as possible to persons with disabilities, but there are many other reasons that the things that make a building accessible would benefit the majority of the hypothetical other users of my hypothetical student project - it's not a "building about disability." Just something I would like to incorporate into part of a bigger system.

To address vado's comment about the ramp-stair in IIT not being ADA - it may not meet ADA standards (you know a lot more about that than I do), but the ADA isn't perfect, nor does it detail every potential solution. Designers could probably invent a lot of ways to make things more accessible that aren't acknowledged (or perhaps are even prevented) by ADA. The IIT stair-ramp may work for people with some types of disabilities but not others: I can see it working for able-bodied people & wheelchair users because they can use the ramp and appreciate the formal qualities of it, but for a blind user it might be more difficult than regular stairs or a plain ramp with fewer switchbacks. I was interested in it because it is indeed an unusual (if not totally unprecedented, though I hadn't seen a project like it before) example of grade transition and sectional variation.

well its certainly possible to design ramps and such that don't meet ada but then you would also have to provide an ada ramp. so what would be the point? as far as ambulatory issues are concerned with the aging population it is already showing up that people want to build single story houses etc...hell in naperville illinoiz they passed an ordinance quite awhile back requiring all new houses to be accessible. the thing that surprises me is how non advanced the idea of the wheelchair is. that's where the research needs to happen.

one (exterior) project that is really interesting formally, but pragmatically a little disfunctional is the 450 golden gate plaza by Della Valle Bernheimer

the SAM olympic sculpture park is another, that is pretty successful as far as functioning for wheelchairs and walkers

outside of mccormick, i'd say offhand, those utilizing ramps in interesting ways would be holl and hadid.

well its certainly possible to design ramps and such that don't meet ada but then you would also have to provide an ada ramp. so what would be the point?

The point: there might be a case in which the ADA ramp (or lift, elevator, etc.) is legally required, but there could be a solution that is better for disabled people, or at least for certain types of disability that the ADA-compliant thing doesn't address. I just imagine situations like... some motorized wheelchairs and scooters are capable of handling a greater slope than the slight one required by ADA, and blind people can climb inclines, and people with difficulty walking might have trouble with stairs and also not want to follow the route of a really long ramp. So some users might prefer a shorter distance/faster time but greater slope to a more circuitous but ADA-compliant path - just like some users prefer to take the stairs. If this were the case, site and user research might then lead a designer to create two slopes: one that is shorter/non-ADA, and one that meets the ADA requirement. Or, maybe some users might like to "off-road" for fun and don't always want everything they use to have a curb/handrail, even though those safeties benefit most people most of the time. I just imagine that because codes can take a while to get into place, and don't always pertain to individual programs, sites, user populations, etc., that sometimes there might be a good reason for some DIY accessibilty. I also think that some other conceptual/formal/contextual/capital-A-Architectural justification could be reason enough for those things. ADA isn't the be-all, end-all, it's just a good start/bare minimum, and some parts of it probably grow obsolete eventually. People have invented techniques for accessibility long before ADA existed so why use strictly ADA. Alternate methods, once demonstrably beneficial, might then eventually expand the code as yet another certified option among all the other techniques. At least I'd hope the guidelines have the potential to absorb developments that way. Thinking of this involves a cultural infrastructure as much as it does a building code.

There are loads of innovations in wheelchair/mobility design whether it's a seated device, or prostheses for people who are able to use them. There is a wheelchair that can climb stairs and that puts the users at eye level... off-road wheelchairs, and so on. As these product-based developments become more common, affordable, & repairable maybe buildings eventually won't need to do as much of the accessibility work. Architecture, products, medical research, etc. all deserve research/thought/attention.

This isn't to say that the example I provided does that, but

...it's just one thing to add to the list of examples. And I don't even know if accessibility was a strong motivator for it (though I suspect it was, I haven't read anything by OMA to indicate it for sure). Maybe they just thought it looked rad or something. I don't know!

Surfaces interesting project. If you don't want to go the route of mechanical access or the ADA compliant 1:5 ramps dominating your program it seems that you may want to squash your levels and bring your first floor down...recalling a hamster wheel.

. It lies somewhere between a mechanical solution and a passive one, taking the users disability and making it into a convenience. Possibly building the space around the user, where the void becomes access.

been feeling futuristic lately -it feels like i'm ghosting me out of my guts; the guts, I’m discovering, is the factory of the deference of my present (then this, in turn, is reminiscent of the mel brooks history of the word clip where a vendor cries: come buy nothing, i have nothing, nothing for sale))

in an age where the generic rules over the poetic, this question is rather eccentric: how does an eccentricity of architecture address an eccentricity of the body i.e. disability. i guess i 'll spraying a per corell graffiti of a rationale here: the disavowal of the idiosyncratic for the sake of the mass. the rubrics being those of ideology and religion.

how will disability move from being an interpretation of the industrial mode (the large adaptation of the world to the body) to that of the cybernetic mode (the small adaptation of the body to the world)? quakes reverberate in the world of the even smaller and smallest, the synthetic plasticky molecules of prosthetics to human meat'n'bone cell cloning. is architecture, in all its awkwardly variable horizontalities and verticalities, continuities and discontinuities, as the unique (and therefore inconsequential) consequence of a designer’s choice on par with the universal hybrid mr./ms. gadget? the anxiety manifest in the domain art criticism concerning authorship and original-ity (a proxy anxiety over the authorship and original-ity of our selves in the galactic graveward of a deceased god) might then manifest itself in the domain of medical ethics and human rights.

relative to the future becoming of ourselves, we are all currently disabled and we will all be augmenting and removing features from our psychic-physiological selves. we won’t be walking to the 100000000000th floor or waiting for a box, we’ll all be flying with the speed of light...we'll all be streaming our selves to any end .flying. then the sun will melt off our wings and our metal hearts, and down we rain, a shower of flesh-slurry and molten minerals. our algebraic souls will dissipate in a puff of numerical nothingness and if a semblance of gods exist, karma will assign us to the spiritual existence of bottle bees in an orchard of venus fly traps.

surface, sorry i didn't make myself more clear. i would say that saying the ramp in the guggenheim has anything to do with disability is a post-rationalization of the project. mccormick is a little different in that koolhaas was specifically trying to accommodate the ada, but the form is really just something that looks kinda cool, and incidentally meets the ada. what i meant by designing specifically for disability is to design for someone who is blind, design for someone who can't walk, etc. what's the difference? take mccormick for example, while koolhaas met the ada, was that really the best circulation for someone in a wheelchair? perhaps. but the form was certainly the driver.

when you write, "I'm being pushed (by both my critic and myself) to develop an "interesting" section for a multilevel studio space." you're doing the same thing - putting the interesting section before the needs of the user. call me old school, but i believe you can generate something much more interesting by starting with the user; in fact, it may be far more surprising than what you anticipated with ramps and level changes.

how will disability move from being an interpretation of the industrial mode (the large adaptation of the world to the body) to that of the cybernetic mode (the small adaptation of the body to the world)?

Adaptive technologies are concurrently being developed on a product scale & as bodily prostheses and cellular engineering, in addition to the architectural/infrastructural scale. It's not a matter of "moving from" buildings to individual bodies as if there is some kind of linear progress involved or there is a conflict between the two. But yes it's good to remember that addressing disability happens in a variety of ways, not just building design.

That said - since I am designing a building, I fail to see the problem with approaching this from the angle of building and landscape design. I hope to do better than a pancake that can be plopped anywhere. A mediocre building that you can roll through easily is not the pinnacle of architectural achievement; people deserve better. The insinuation that accesibility seems to carry the connotation, for some of you, with "dumbing down" a building (making it "mass") is disappointing.

There is also a contingent of disability rights activists who say their bodies do not have pathologies to be adapted/altered with technology/medicine, but are deserving of acceptance, "eccentricities" and all. (They've suggested solutions ranging from building/infrastructural standards to the creation of a national community-based home health attendant system - myyriad different ways to avoid pathologizing disability.) I think there is value/something to be learned from the experiences & voices of people who have different phenomenological experiences, different ways of moving through/seeing/feeling the world, and that all of them can contribute to architecture and offer new ways to approach it. With this stance, the ableist way of thinking and designing is the thing that is archaic, limiting, for the almost-but-not-quite mass. Accessible designs can certainly have idiosyncrasies, just as inaccessible buildings can be homogenous or bound to an ideology. The accessibility of something has nothing inherently to do with that. The projects holz.box and Steven Ward have been posting start to demonstrate this.

It would be a lot easier to get around adapting buildings/infra to bodies instead of the other way around if every single person could afford a $25,000 super-wheelchair or $40,000 prosthetic limbs and $250,000 worth of medical appointments to get fitted with them. There's a revolution of healthcare system/economics/etc. to be had along with going in a more cybernetic direction.

Besides, even with the resources to pick and choose, some people like those in dammson's link clearly still find value in investing in a giant kinetic platform.

jafidler - I actually agree with you on the user-based approach. BUT. That is how I already know how to approach things; it's conventional for me. I don't have an architecture background either professionally or academically (I have actually done more community activism, product design, user-centered design, etc.), and have never done a project driven by thinking about sectional variation. My instinct is to dismiss it as ridiculous, and I'm pretty committed to designing in a user-based manner in general. BUT. I am in school, and I want to attempt new ways of approaching design, and honestly no one is ever going to build this, and it's part of a mid-term phase of the project, not even the final. So, why not spend a couple weeks designing via sectional variation, to learn from it? There's validity in that too.

Also, I don't really want to "design specifically for disability." I would like to start thinking about designing "Universally," which I define as equally inclusive of the entire spectrum of able-bodied and disabled people, many of whom can appreciate designs with non-disability-driven concepts, or a form that "just looks cool" (or in the case of blind people, has some other sensory/phenomenological specificities). Sometimes, I feel like the user-based rhetoric contains an embedded assumption (even though I believe you don't actually think this!) that people with disabilities can't or don't understand or appreciate anything about design besides that which directly addresses disability.

re: Guggenheim - for my purposes, it doesn't matter whether an architect to deliberately addressed disability in order for al design that works for disabled people to enter into this discussion as a precedent. (I doubt disability was a primary motivator for Mercedes-Benz, either.) I plucked the example from the blog of adisability scholar/activist, entitled The Right to Design where she quotes a wheelchair user/activist who loves it. FLW may or may not have had disability in mind. FLW may have had a conceptual idea about smooth transitions. He may have wanted to test it as a way to move large artworks throughout the building. He may have wanted people to have bike races indoors or be drunkenly rolled down it in barrels. And it doesn't matter - it's working for some people with disabilities so it belongs here and architects can still learn from it.

rather than challenging someone's design process* i'll start by simply contributing to the precedent list...

Kunsthal Rotterdam by OMA

this exterior path that bisects the building falls into the "greater slope" category. it's a wonderful way to move from the lower grade of the park to the higher grade of the street (or vice versa). it's accessible in more than one way.

it may be a difficult [unassisted] climb in a typical wheelchair, but there is at least one opportunity for pause on flat ground (at the entrance, see next two pics)...

interior circulation:

anyway, worth looking at the Kunsthal, as it has, at least in part, an effective and engaging itinerary of sectional spaces via inclined plane.

another OMA project that does this well is the Educatorium (again, an only in part effective use of inclined planes that relies on lifts and stairs for portions of the circulation)...

/precedent

*i do think that challenging the question/request is valid, and i expect that aspect of this thread will result in some useful dialogue.

Also I don't mind challenges to the question. I just get irritated REAL FAST with assumptions that I haven't thought through that stuff already. Architects can be so quick to dismiss/assume the worst and it just feels condescending, even if it isn't meant to be. (Given how much I wrote up there eventually, imagine if the initial post were long enough to clarify a broad swath of what I have thought about or previously researched. TL;DR!)

Lifts are valid modes of transition too (and certainly more economical in floor space) and would be interested in precedents that use them well, especially in non-standard ways - I'm not only interested in ramps. But - after spending a couple of months in a building in which at least one of the elevators is perpetually broken or under repair, the ability to avoid relying on mechanical systems has its appeal.

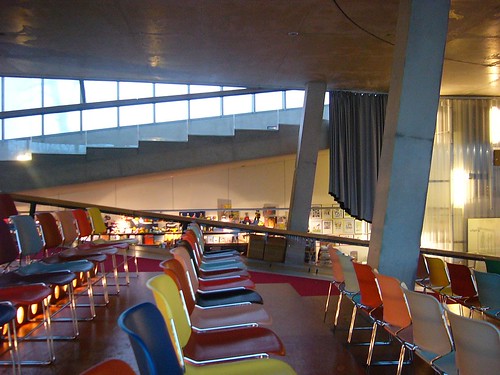

In the examples AP posted, pretty cool. The main thing I can see as being problematic is actually the auditorium with the multicolored chairs. I would prefer to avoid seating (or doors, or sizes of rooms, or whatever) that dictate what size people should be... sizeism enacted through standardized chair dimensions is not my cup of tea either. I'd use a bench system (long continuous seating) or perhaps better yet, a modular system that allowed users to push seat units together into bigger or smaller chunks depending on # and size of people. This would also allow people to define their groups of friends, preserve personal space so some creep can't sit too close on the bench, possibly cram in more people on a crowded lecture, etc. & could still preserve the color-pixel design effect when the auditorium is empty.

Oct 21, 08 11:52 am ·

·

Susan, discerning the likely precedents does actually matter because you can then better understand the design process. Momo most likely looked at the earlier Vatican ramp.

"There is a spiral 'staircase', designed by Bramante c. 1504, which allowed individuals on horseback access up to the Vatican's Belvedere Palace (which today comprises much of the Vatican Museum) from the street level several stories below."

It is not a stretch to connect horseback to automobile to wheelchair and their relation to ramps within architectural designs.

Wrights ramps (at the Guggenheim) are very evolved beasts.

ps

The Mercedes-Benz Museum is by UnStudio, not H&dM.

i hate to keep harping on this but that kunsthalle ramp don't meet ada either. the fact that when you deal with these issues over and over you begin to think in those terms. the first question you ask yourself is this fucker ada compliant? and maybe you can design ten different ramps with one being the ada compliant ramp. but when timmy goes over the edge of the ramp that doesn't comply, then you have problems.

Arrgh, another case of people totally not reading what I am actually saying. (If I thought that looking at precedents didn't matter, why would I post a thread... asking if anyone knew of some precedents?) I just meant that I don't really care if someone has "copied" a previous design (not problematic) or if it is an original technique.

& oops, my bad on the UN/HdM confusion. Sorrryyyyyy UNStudio.

Oct 21, 08 12:02 pm ·

·

And Susan, I too could say you missed the point because it wasn't "oh look, Wright copied!" rather look at what it was that Wright further reenacted. Momo's design is actually a quite modern people mover within architecture, as opposed to (first) a vehicular mover. And, since it's a double helix, there's even something universal about it.

here's a precedent. the romans in order to capture masada built ,or rather had there slaves build, ramps up the shear cliff sides to slaughter themselves some jewish rebels. who surprise already killed themselves.

SurfaceS:That said - since I am designing a building, I fail to see the problem with approaching this from the angle of building and landscape design

i personally don't see it as a problem, i just see it as being trivial. not trivial because its a trivial ambition or a trivial outcome but because as opposed to each one building having to tortuously conform to standards that never really address all disabilities anyway, the solution should be in the assisted evolution of the body to address all and any potential obstacle. by calling this exercise on the part of the architect trivial, I’m not implicitly claiming that the involved architect is not honorable or that this one edifice of hers does not make the world a better place, I hope you understand.

SurfaceS "There is also a contingent of disability rights activists who say their bodies do not have pathologies to be adapted/altered with technology/medicine..."

i also said:

relative to the future becoming of ourselves, we are all currently disabled and we will all be augmenting and removing features from our psychic-physiological selves.

that is to say, disability alters with the alteration of the denominator, the norm - and by person, i also include the sum of her parts, including those that would be added (whether mineral or biological), even by virtue of subtraction, should that be the case.

and concurrent would be the change in what constitutes natural and artificial. hence, i bring up the anxiety of authenticity and original-ity we exorcise into art.

the anxiety manifest in the domain art criticism concerning authorship and original-ity (a proxy anxiety over the authorship and original-ity of our selves in the galactic graveyard of a deceased god) might then manifest itself in the domain of medical ethics and human rights.

in spite of that, art has been created out of this very anxiety over art (prototypically, duchamp). therefore, inspite of this anxiety we have over what corporeally belongs, or rather is us (and this goes to address SurfaceS: is also a contingent of disability rights activists who say their bodies do not have pathologies to be adapted/altered with technology/medicine, but are deserving of acceptance, "eccentricities" and all.), the changes in our understanding of corporeality will be naturally(haha not) in synch with the growing space of virtuality in our life, with the increasing inorganicity of our daily lives. a caliber of abstraction that confounds the mineral with the organic. those disability rights activists are only basing their understanding of their disability on the traditional belief in corporeal originality in an age that is heading towards a complete en-abling of everyone else. i totally understand their nostalgia – and it is nostalgia- for a sacrosanct corporeality, but its clear this is not the physically secular future we're heading towards.

don't be offended, surfaces. this is all pretty tame compared to the responses you would get in a review. i think it's awesome that your background is in community activism and industrial design. that seems like the perfect combo for just the project you are working on, but instead of trying to "architecturalize" the project with an "interesting" section, i would use your background to second guess what the architecture actually is.

you're absolutely right about "universal" design which is why my criticism of the ramps in mccormick is unfair. those ramps do address a condition that makes access universal and should not be designed specifically for the disabled. BUT...from the jist of this thread, i was assuming that the point of your studio was designing for the disabled in which case the universal aspect perhaps is not as important as the specific user (a point you will need to take a clear stand on.) i have no doubt you have thought through these issues far more than i have as i type away on my lunch hour, but i'm just offering a different perspective for you to dimiss as you see fit.

yes this is it. trivial because its always about one instance of now

then this goes back to my issue with my guts and the deference of the present/the now. i don't know how to come to terms with the hollywoodish seemingly happy-go-lucky koan (more like a steely will with the optional addition of denial) to 'live each moments like its your last'. and i admit it, i'm scared. i don't understand how those blonde cocks arent fucking terrified.

FYI - the point of my studio is NOT design for the disabled. (It just has, at the very end of the program brief, as tacked on at the end of all of our program briefs because NCARB requires it, one sentence along the lines of "All student work must conform to ADA standards.") This is something I'm interested in working through in the broader context of the project, which is an arts and sciences university building. I think one should consider this regardless of WHAT one is designing, so I am. It's just one thing I'm thinking about, the one thing I'm choosing to discuss here - which, by the way, isn't even the conceptual underpinning of the project.

jafidler - I should also admit here that due to aforementioned "alternative" bacoground, I kind of also just want to learn to make a decent drawing for once, instead of a sad, unclear, butt-ugly drawing that makes the critics say nothing more about it than "um... you need to learn how to draw a section." Hahaha. I can't help but second-guess the more typical architecture pedagogy, and while I like doing that, I don't think it is inherently productive. At some point I do want to step back and, in a way, second-guess my own tendency to second-guess. I think my critic has asked me to think about it differently than I have been because he thinks I would benefit/learn from spending time on this approach and I can accept that. & I know that I can improve my drawing within any conceptual framework too. OK, that is my personal architecture TMI.

vado - Kunsthalle is not even in the A (of the Americans with Disabilities Act) - I guess they can deal with their own standards.

I don't think it's entirely this simple, not at all. But there seems to be a line of thought in disability activism that holds, basically, that if more architects (and product designers, and others...) had committed to at least attempting UD once it was pointed out to them that multi-levels and stairs and curbs don't work for many people, it wouldn't have been necessary to institute such a labyrinthine set of codes to legally force architects & planners extremely prescriptive ways of doing so simply because they're total dismissive jerks about disability otherwise.

I get the sense that some of the stringency of ADA regs is not due only to actual safety concerns, nor even governmental bureaucracy and tendency to simplify/standardize things - but largely comes from the assumption that most architects/planners/etc. fundamentally don't care about disabled people's needs, at least not enough to address them without being legally obligated. And therefore disability advocates insist upon extremely stringent/prescriptive regulations in order to protect themselves, and this regulation (and activism) has elements of antagonistic/hostile undercurrents toward architectural design.

I mean stuff like this, from the article posted from Metropolis: For most of my life I have had a love-hate relationship with architecture and architects. It has generally been my experience that the making of physical spaces to welcome people in wheelchairs has ranked on the low end of the scale of importance for most architects, down there with selecting the paint for a stairwell. Accessibility is fine for ugly strip malls in Texas but somehow eludes the stair-encrusted Four Seasons Hotel in Man-hattan. Universal design seems like more of an architectural afterthought than a central tenet of building, even today.

Given that, I really cannot see a problem with trying to sort out working approaches in general, not merely ADA-complaint ones. Alternatives, including designs like the OMA Kunsthalle which has its proving ground outside of the jurisdiction of the ADA, might even eventually become accepted into ADA standards after some lobbying and so on.

Howski - Momo = FLW? (sorry, just have never heard that nickname.)

ada is an american civil rights act and has nothing to do with the kunsthall or the educatorium. both are brilliant, and are accessible without being about accessibility. while they may have to be done slightly differently if built in the u.s., the strategies driving their internal relationships could be maintained. very strange for such a flat country but the dutch use of sectional manipulation (even pre-koolhaas) is inspired/inspiring!

ada is a minimum standard which, in many cases, is actually counter-productive. i worked on an elementary school for children with severe physical disabilities and ada just plain didn't work. we had to get special dispensation from code enforcement to NOT meet ada at the petitioning of the staff.

susan is my hero in this. she's got just the right level of curiosity and passion and is already pretty knowledgeable not just about the obvious accessibility issues but about the attitudes and lifestyle implications behind them.

i do think that you could give less attention to an 'interesting section', though, susan. if you are designing on multiple levels and designing for universal access, section will happen. do you already have a site? the topography may end up having as much impact on both access and section as anything else.

one more example of something that may be less 'interesting' and less in-your-face, but may point to a way of coming up with simpler, quieter accommodation. this shelter:

it's an overlook shelter in an olmsted park. the bench in the middle was actually a solution before it was a bench. the goal was an open prospect from the highest point of the steps. the primary approach to the shelter was from the opposite side. the landscape architect designed the seat-steps to cascade down the slope, but this created a potential hazard for a wheel-chair user coming into the shelter and out to the edge. the bench acts as a very simple stop while also providing additional amenity.

relative to the future becoming of ourselves, we are all currently disabled and we will all be augmenting and removing features from our psychic-physiological selves.... those disability rights activists are only basing their understanding of their disability on the traditional belief in corporeal originality in an age that is heading towards a complete en-abling of everyone else. i totally understand their nostalgia – and it is nostalgia- for a sacrosanct corporeality, but its clear this is not the physically secular future we're heading towards.

There is a term in disability-speak, "Temporarily-Able-Bodied." or "TABs" TABs are people like myself who don't currently have disabilities, as a reminder that anyone might become disabled someday. Disability rights activists are hardly married to "corporeal originality," since as far as I can tell there is as much desire/advocacy for advancement in prostheses, biological solutions, and other body-direct things, as there is for accessible spaces. Taking issue with the pathologization of disability has more to do with the attitudes with which it disability approached and how it results in treating disabled people like problems or second-class citizens, and is not a refusal of technological solutions or biologically based ones.

I don't think it is more forward-thinking to view all people as "currently disabled." Why is it more futuristic to pathologize all bodies, rather than challenging the idea of what should be pathologized? It could (should?) go both ways so I don't think we have a disagreement on this. I just don't think we can dismiss as mere clueless nostalgia the experiences/voices of disabled people - who inhabit the world AS IT IS NOW, and not how it might be someday in the hypothetical cybernetic future when corporeality isn't an issue. Prostheses and digitalization are great... if a) you can afford them, and b) you didn't RIGHT NOW need to get into the post office, etc. If/when we get to the ideal cybernetic moment in time, I think I'd still believe that people should have the right to choose whether they wanted in-body modifications, or other accommodations that allowed them to use only their natal bodies. FWIW, I don't personally believe that technology or modification are unnatural or inorganic - in fact, quite the opposite. (I also support transgender rights - therefore, definitely not one of the "stick to the body you're born with" crowd.) Humans, human activity, the tendency to modify bodies/environments, are part of organic nature, not something outside of/opposed to it. One of my biggest peeves is when "nature" is thrown about as a subsitute for "stuff humans didn't do."

Steven, I totally dug my own grave by saying 'Interesting section.' That's just my shorthand for well-thought out, spatially considered, relating-to-my-concept, section. My critic is a lot more thoughtful than someone who would just assign "interesting drawing" and I'm making him look bad! If you are reading this, sorry dude! Actually I am paranoid that he could be reading this and is banging his head thinking "why aren't you DOING your homework!!" and yes, I should just - start - designing. NOW! I will be back later I'm sure.

ada is a minimum standard which, in many cases, is actually counter-productive. i worked on an elementary school for children with severe physical disabilities and ada just plain didn't work. we had to get special dispensation from code enforcement to NOT meet ada at the petitioning of the staff.

I've heard other anecdotes about things like this happening - not only instances in which ADA was actually a disservice to the building's disabled users, but instances in which someone lobbied to adapt the ADA regs in order to make the building accessible - clearly it can happen! That's why I'm not just interested in accepting ADA compliance as a limitation.

yes i know those buildings are not in the usa. neither is masada. but i am in the usa and that's what i am responding to. actually i forgot but there is a school in indianapolis that was built in the 30's that was the first accessible school... the school system wants to demolish it and replace it with a parking lot. which i am sure will have many handicapped spaces.

SurfaceS: "There is also a contingent of disability rights activists who say their bodies do not have pathologies to be adapted/altered with technology/medicine, but are deserving of acceptance, "eccentricities" and all. "

SurfaceS: "Disability rights activists are hardly married to "corporeal originality," "

I refer to the same contingent you refer to. your first quoted statement says that this contingent are "married to "corporeal originality"" and this contingent is therefore nostalgic. its funny how I suspect that you dismiss nostalgia as if it were something implicitly negative, flaccid, extraneous and functionless. i would argue that nostalgia has a great and complex role in our present and will in our future. what (hello lauf) reenactment but the rituals of nostalgia. what is religion but the nostalgic hankering after originality.

there was no need for you to point out that somewhere else, adhering to another contingent (which is altogether besides the point), is the:

SurfaceS: " desire/advocacy for advancement in prostheses, biological solutions, and other body-direct things, as there is for accessible spaces"

as for :

SurfaceS: "Why is it more futuristic to pathologize all bodies, rather than challenging the idea of what should be pathologized? "

i did not pathologize anything; in fact, what you may more correctly deduce that the gist of my sketch was that this pathology itself will cease to exist with the increasing secularization of the flesh - which we witness in genetic cloning, in our dietary staple, in the compound intelligence of mineral and living-tissue. these are domains that are changing the world we live in, whereas your ethical contestation and critique con pathology and negative fetishization (even positive), whilst at best, could help establish a subsidiary department in the UN and create human flesh-rights groups all which will have as much clout as the UN does now apropos humans inflicting violence on their own kind. contesting and critiquing has done very little to better the world relative to the crap that’s inflicted this planet by the self-propelled non-reflexive technological jumps taken in the aim of improving the affairs of a select few. i hope you now see that i see you as being irrationally optimistic about the future of a self destructive species that proves how self destructive it is, over and over again.

anyway: the more secular the flesh, the less the taboos surrounding it, the less pathologically charged it is. so, yes, i believe our future will change our bodies as it changes our understanding of our bodies. after all, what tides into and out of 'pathology' is that of the relevant cultural époque. and keep in mind, i said we are disabled relative to our future selves. this is a truism and not a fetishization ie a pathology: if i now deprive you of electricity, you will feel dis-abled because your denominator is the present/now and your nominator is the harkening of the past via technological dis-abling. as such, the city would live a fiction (the fraction is, unlike addition or subtraction, a fiction) of the past intruding in on the present. no pathology there. the city cannot exist with the present infrastructure of its reality whilst observing the conditions of the past (no electricity). thus, a dis-abled city. by creating a fraction of present tense over future tense, the concern is not ethical (therefore not pathological) as it is exemplarily fictional (the creation of one other reality).

i also wish to add (because i was visualizing a missing part of the argument on my part prior to dosing off yesternight) that: by trivial, i do not see the effect of architecture as being trivial ... but the degree by which it is effective in the larger scheme of things, compared to a solution (mind the pathology) ... (now mind the weak pun) closer at hand. it is the small mitochondria that is the actual powerhouse of the body and not the cow or the zucchini. the future lies in the mitochondria itself not in the cow ... our world of artifice (anthropomorphized nature) is merely a reflection of our obsession over ourselves. once we realized how naked we were, the adam and eve thing, we set about recreating the whole world, including the innards of our bodies, to conceal our nakedness.

Interesting ADA / Universal Design / Accessibility solutions

Hi Archinect!

I'm hoping that some of you might be able to help me out with a current studio conundrum. Sometimes I like to beg for free advice without doing any real research, too! (just kidding - I hit "search.")

Do any of you know of particularly notable projects that address accessibility successfully/interestingly - whether or not they are actually ADA-compliant, and whether or not accessibility was a design objective or simply a result of some other conceptual/formal process.

I just posted about this in my school blog & I'm thinking of things like

OMA's McCormick Center at IIT,

FLW's Guggenheim Museum in NYC

H&DM's Mercedes Benz Museum

...and the like.

There are a few typical ways to address accessibility to people with mobility difficulty (I'm barely even dealing with, for example, blindness right now). Lifts, elevators, ramps, or putting things all on one floor.

So I'm faced with this issue: I'm being pushed (by both my critic and myself) to develop an "interesting" section for a multilevel studio space. A non-pancake-stack-with-elevators section. Intuitively, it seems that lots of level changes might not be the most ideal way to go about designing, if one's goal is to have a disability-positive building (as opposed to one that is jimmy-rigged into accessibility) but I also certainly don't think that designing for disability precludes this kind of variety, if done well. I'd like to know of a few more precedents Is there anything I haven't thought of yet/don't know about? Anything flamingly awesome? I barely even know how to talk about this!

from your examples, it sounds like you are simply interested in any building with a ramp of which there are obviously many. you may find it more interesting and challenging to take on disability specifically rather than a post-rationalized architectural response to disability. i don't know if that is helpful or not.

Corb did a lot of really buildings that had ramps. I'd to see someone do ADA like Glenn Murcutt is interested in the environment.

susanS, great thread. i am curious though, how would you as an architect design for a physically challenged athlete? say one of the Murder Ball guys? it seems that given the obvious - we are all different, i could think of a situation where many athletes with physical challenges would welcome a "hostile" environment or rough terrain.

that oma ramp aint ada. 6" rise requires railing.

on both sides, too!

there was some competition years ago, i think it was a 'house for a blind person' or something .. one submittal was basically a series of 3' corridors so the blind person would be able to feel their way around. my memory is sketchy but the plan had all these thick walls,used poche, and focused on surface textures as opposed to space.

then a year or two ago there was a t.v. show on one of those channels (hgtv? discovery channel?) with a blind guy who worked as a consultant when designers were working on spaces for the blind. i gotta start writing this stuff down i'm starting to lose it ..

you want me to design something for you FRandC. i do a lot of work for the senile.

this project fits the question(s) - or at least is designed to: http://www.flickr.com/photos/archintentlouisville/sets/72157601281040641/

this is a rec center on a public park specifically designed to accommodate people with physical disabilities. not that it serves them exclusively - the client's goal is to be fully open and to make the place desirable enough that anyone/everyone will want to participate together. see: http://www.themvpzone.org/

the design challenge we took on: to make everything as much as possible about 'access'. for us that meant:

- setting the building down into the landscape so that everyone could come right out from grade onto each level (incl the roof terrace) to look over the landscape,

- suppress any stairs in favor of ramping or elevator,

- make the volume as open as possible so that it could be comprehensible from anywhere inside

- etc - basically anything we could think of that pushed the idea of 'access' at any program or activity area.

program includes aquatic center, golf/pro shop (artificial turf @ tees and greens), courts (including those designed for wheelchair rugby aka murderball), track, multipurpose room (tennis, indoor soccer), dance/movement space, computer rooms...

this one: http://www.flickr.com/photos/archintentlouisville/sets/72157602875699075/

...

...was a landing for a steamboat. designed to get people down a 40' bluff to the dock level, then to accommodate as much as 20' of rise and fall of the river. boarding could happen at any of the four levels, depending on water elevation, during sailing season. a funicular brings people down to the top level and then ramps connect each tier.

archinect touched on some aspects previously

I used the terms ADA, Accessible, and Universal Design, because they all mean slightly different things.

jafidler - "ramp buildings" qua "ramp buildings" are certainly not my only interest. (Something that does interest - or rather annoy - me, however, is the designation of "ramp buildings" as a specific kind of architecture, especially when connoted pejoratively with trendiness - maybe I'm reading more into your comment than I should though.) I'm not sure what you mean by "you may find it more interesting and challenging to take on disability specifically rather than a post-rationalized architectural response to disability." I am trying to avoid a way of thinking that would be described as "post-rationalized." I don't think it would be more interesting to focus on "disability" broadly rather than architectural considerations of disability. There is a whole body of scholarship/research/theory/activism devoted to disability, and that oeuvre is way, way beyond my scope right now. From the small amount of research and conversation I have had with researchers & activists in the area, it appears that many people WANT architects to put more effort into addressing disability with architecture. Since I am working on an architectural design assignment, I actually consider architectural responses to disability to be the most interesting approach.I personally tend toward really simple/pared-down solutions to things, so gradual transitions of grade (ramps) or eliminating # of floors are first-line appealing, as opposed to 37 level changes with a mechanical lift at each skip, or handing every user of my building a jet-pack upon crossing the threshhold. (No, wait, relying on jet-packs to make my building accessible is actually AWESOME.) That said - I want my building to be as accessible as possible to persons with disabilities, but there are many other reasons that the things that make a building accessible would benefit the majority of the hypothetical other users of my hypothetical student project - it's not a "building about disability." Just something I would like to incorporate into part of a bigger system.

To address vado's comment about the ramp-stair in IIT not being ADA - it may not meet ADA standards (you know a lot more about that than I do), but the ADA isn't perfect, nor does it detail every potential solution. Designers could probably invent a lot of ways to make things more accessible that aren't acknowledged (or perhaps are even prevented) by ADA. The IIT stair-ramp may work for people with some types of disabilities but not others: I can see it working for able-bodied people & wheelchair users because they can use the ramp and appreciate the formal qualities of it, but for a blind user it might be more difficult than regular stairs or a plain ramp with fewer switchbacks. I was interested in it because it is indeed an unusual (if not totally unprecedented, though I hadn't seen a project like it before) example of grade transition and sectional variation.

well its certainly possible to design ramps and such that don't meet ada but then you would also have to provide an ada ramp. so what would be the point? as far as ambulatory issues are concerned with the aging population it is already showing up that people want to build single story houses etc...hell in naperville illinoiz they passed an ordinance quite awhile back requiring all new houses to be accessible. the thing that surprises me is how non advanced the idea of the wheelchair is. that's where the research needs to happen.

one (exterior) project that is really interesting formally, but pragmatically a little disfunctional is the 450 golden gate plaza by Della Valle Bernheimer

the SAM olympic sculpture park is another, that is pretty successful as far as functioning for wheelchairs and walkers

outside of mccormick, i'd say offhand, those utilizing ramps in interesting ways would be holl and hadid.

The point: there might be a case in which the ADA ramp (or lift, elevator, etc.) is legally required, but there could be a solution that is better for disabled people, or at least for certain types of disability that the ADA-compliant thing doesn't address. I just imagine situations like... some motorized wheelchairs and scooters are capable of handling a greater slope than the slight one required by ADA, and blind people can climb inclines, and people with difficulty walking might have trouble with stairs and also not want to follow the route of a really long ramp. So some users might prefer a shorter distance/faster time but greater slope to a more circuitous but ADA-compliant path - just like some users prefer to take the stairs. If this were the case, site and user research might then lead a designer to create two slopes: one that is shorter/non-ADA, and one that meets the ADA requirement. Or, maybe some users might like to "off-road" for fun and don't always want everything they use to have a curb/handrail, even though those safeties benefit most people most of the time. I just imagine that because codes can take a while to get into place, and don't always pertain to individual programs, sites, user populations, etc., that sometimes there might be a good reason for some DIY accessibilty. I also think that some other conceptual/formal/contextual/capital-A-Architectural justification could be reason enough for those things. ADA isn't the be-all, end-all, it's just a good start/bare minimum, and some parts of it probably grow obsolete eventually. People have invented techniques for accessibility long before ADA existed so why use strictly ADA. Alternate methods, once demonstrably beneficial, might then eventually expand the code as yet another certified option among all the other techniques. At least I'd hope the guidelines have the potential to absorb developments that way. Thinking of this involves a cultural infrastructure as much as it does a building code.

There are loads of innovations in wheelchair/mobility design whether it's a seated device, or prostheses for people who are able to use them. There is a wheelchair that can climb stairs and that puts the users at eye level... off-road wheelchairs, and so on. As these product-based developments become more common, affordable, & repairable maybe buildings eventually won't need to do as much of the accessibility work. Architecture, products, medical research, etc. all deserve research/thought/attention.

This isn't to say that the example I provided does that, but

...it's just one thing to add to the list of examples. And I don't even know if accessibility was a strong motivator for it (though I suspect it was, I haven't read anything by OMA to indicate it for sure). Maybe they just thought it looked rad or something. I don't know!

Surfaces interesting project. If you don't want to go the route of mechanical access or the ADA compliant 1:5 ramps dominating your program it seems that you may want to squash your levels and bring your first floor down...recalling a hamster wheel.

. It lies somewhere between a mechanical solution and a passive one, taking the users disability and making it into a convenience. Possibly building the space around the user, where the void becomes access.

. It lies somewhere between a mechanical solution and a passive one, taking the users disability and making it into a convenience. Possibly building the space around the user, where the void becomes access.

giant floorplate full of people in hamster wheels... wow... what a mental image to put me to sleep tonight.

dammson i think that was the obvious that she was moving beyond

been feeling futuristic lately -it feels like i'm ghosting me out of my guts; the guts, I’m discovering, is the factory of the deference of my present (then this, in turn, is reminiscent of the mel brooks history of the word clip where a vendor cries: come buy nothing, i have nothing, nothing for sale))

in an age where the generic rules over the poetic, this question is rather eccentric: how does an eccentricity of architecture address an eccentricity of the body i.e. disability. i guess i 'll spraying a per corell graffiti of a rationale here: the disavowal of the idiosyncratic for the sake of the mass. the rubrics being those of ideology and religion.

how will disability move from being an interpretation of the industrial mode (the large adaptation of the world to the body) to that of the cybernetic mode (the small adaptation of the body to the world)? quakes reverberate in the world of the even smaller and smallest, the synthetic plasticky molecules of prosthetics to human meat'n'bone cell cloning. is architecture, in all its awkwardly variable horizontalities and verticalities, continuities and discontinuities, as the unique (and therefore inconsequential) consequence of a designer’s choice on par with the universal hybrid mr./ms. gadget? the anxiety manifest in the domain art criticism concerning authorship and original-ity (a proxy anxiety over the authorship and original-ity of our selves in the galactic graveward of a deceased god) might then manifest itself in the domain of medical ethics and human rights.

relative to the future becoming of ourselves, we are all currently disabled and we will all be augmenting and removing features from our psychic-physiological selves. we won’t be walking to the 100000000000th floor or waiting for a box, we’ll all be flying with the speed of light...we'll all be streaming our selves to any end .flying. then the sun will melt off our wings and our metal hearts, and down we rain, a shower of flesh-slurry and molten minerals. our algebraic souls will dissipate in a puff of numerical nothingness and if a semblance of gods exist, karma will assign us to the spiritual existence of bottle bees in an orchard of venus fly traps.

surface, sorry i didn't make myself more clear. i would say that saying the ramp in the guggenheim has anything to do with disability is a post-rationalization of the project. mccormick is a little different in that koolhaas was specifically trying to accommodate the ada, but the form is really just something that looks kinda cool, and incidentally meets the ada. what i meant by designing specifically for disability is to design for someone who is blind, design for someone who can't walk, etc. what's the difference? take mccormick for example, while koolhaas met the ada, was that really the best circulation for someone in a wheelchair? perhaps. but the form was certainly the driver.

when you write, "I'm being pushed (by both my critic and myself) to develop an "interesting" section for a multilevel studio space." you're doing the same thing - putting the interesting section before the needs of the user. call me old school, but i believe you can generate something much more interesting by starting with the user; in fact, it may be far more surprising than what you anticipated with ramps and level changes.

Adaptive technologies are concurrently being developed on a product scale & as bodily prostheses and cellular engineering, in addition to the architectural/infrastructural scale. It's not a matter of "moving from" buildings to individual bodies as if there is some kind of linear progress involved or there is a conflict between the two. But yes it's good to remember that addressing disability happens in a variety of ways, not just building design.

That said - since I am designing a building, I fail to see the problem with approaching this from the angle of building and landscape design. I hope to do better than a pancake that can be plopped anywhere. A mediocre building that you can roll through easily is not the pinnacle of architectural achievement; people deserve better. The insinuation that accesibility seems to carry the connotation, for some of you, with "dumbing down" a building (making it "mass") is disappointing.

There is also a contingent of disability rights activists who say their bodies do not have pathologies to be adapted/altered with technology/medicine, but are deserving of acceptance, "eccentricities" and all. (They've suggested solutions ranging from building/infrastructural standards to the creation of a national community-based home health attendant system - myyriad different ways to avoid pathologizing disability.) I think there is value/something to be learned from the experiences & voices of people who have different phenomenological experiences, different ways of moving through/seeing/feeling the world, and that all of them can contribute to architecture and offer new ways to approach it. With this stance, the ableist way of thinking and designing is the thing that is archaic, limiting, for the almost-but-not-quite mass. Accessible designs can certainly have idiosyncrasies, just as inaccessible buildings can be homogenous or bound to an ideology. The accessibility of something has nothing inherently to do with that. The projects holz.box and Steven Ward have been posting start to demonstrate this.

It would be a lot easier to get around adapting buildings/infra to bodies instead of the other way around if every single person could afford a $25,000 super-wheelchair or $40,000 prosthetic limbs and $250,000 worth of medical appointments to get fitted with them. There's a revolution of healthcare system/economics/etc. to be had along with going in a more cybernetic direction.

Besides, even with the resources to pick and choose, some people like those in dammson's link clearly still find value in investing in a giant kinetic platform.

jafidler - I actually agree with you on the user-based approach. BUT. That is how I already know how to approach things; it's conventional for me. I don't have an architecture background either professionally or academically (I have actually done more community activism, product design, user-centered design, etc.), and have never done a project driven by thinking about sectional variation. My instinct is to dismiss it as ridiculous, and I'm pretty committed to designing in a user-based manner in general. BUT. I am in school, and I want to attempt new ways of approaching design, and honestly no one is ever going to build this, and it's part of a mid-term phase of the project, not even the final. So, why not spend a couple weeks designing via sectional variation, to learn from it? There's validity in that too.

Also, I don't really want to "design specifically for disability." I would like to start thinking about designing "Universally," which I define as equally inclusive of the entire spectrum of able-bodied and disabled people, many of whom can appreciate designs with non-disability-driven concepts, or a form that "just looks cool" (or in the case of blind people, has some other sensory/phenomenological specificities). Sometimes, I feel like the user-based rhetoric contains an embedded assumption (even though I believe you don't actually think this!) that people with disabilities can't or don't understand or appreciate anything about design besides that which directly addresses disability.

re: Guggenheim - for my purposes, it doesn't matter whether an architect to deliberately addressed disability in order for al design that works for disabled people to enter into this discussion as a precedent. (I doubt disability was a primary motivator for Mercedes-Benz, either.) I plucked the example from the blog of adisability scholar/activist, entitled The Right to Design where she quotes a wheelchair user/activist who loves it. FLW may or may not have had disability in mind. FLW may have had a conceptual idea about smooth transitions. He may have wanted to test it as a way to move large artworks throughout the building. He may have wanted people to have bike races indoors or be drunkenly rolled down it in barrels. And it doesn't matter - it's working for some people with disabilities so it belongs here and architects can still learn from it.

[or maybe Wright looked at the Vatican or remembered the Gordan Strong Automobile Objective]

Or maybe he looked at Xochitécatl

or some Ziggurats

and then inverted solid/void. Or maybe the Vatican designers did. It's not like the Vatican was the first spiral ramp ever... or like it matters?

ps Howski thanks for the M. Graves link... hadn't seen that one before.

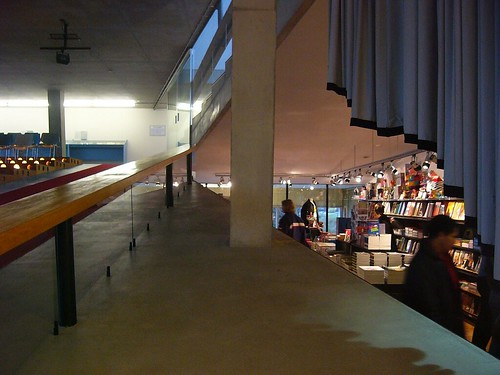

rather than challenging someone's design process* i'll start by simply contributing to the precedent list...

Kunsthal Rotterdam by OMA

this exterior path that bisects the building falls into the "greater slope" category. it's a wonderful way to move from the lower grade of the park to the higher grade of the street (or vice versa). it's accessible in more than one way.

it may be a difficult [unassisted] climb in a typical wheelchair, but there is at least one opportunity for pause on flat ground (at the entrance, see next two pics)...

interior circulation:

anyway, worth looking at the Kunsthal, as it has, at least in part, an effective and engaging itinerary of sectional spaces via inclined plane.

another OMA project that does this well is the Educatorium (again, an only in part effective use of inclined planes that relies on lifts and stairs for portions of the circulation)...

/precedent

*i do think that challenging the question/request is valid, and i expect that aspect of this thread will result in some useful dialogue.

Nice photos.

FWIW, ADA requires that accessible ramps have a maximum rise-run ratio of 1:12, with a maximum rise of 30" between landings.

mvrdv's anyang peak:

which is in the same ilk as those above, though the ramp is essentially a continuous loop

That is nice, hadn't seen that project.

Obligatory Arrested Development reference: "Anyang!"

PS - isn't it also the case that if a slope is < 1:20, it qualifies as simply a 'floor' and then doesn't need landings, railings, etc.?

AP - thanks for the advice!

Also I don't mind challenges to the question. I just get irritated REAL FAST with assumptions that I haven't thought through that stuff already. Architects can be so quick to dismiss/assume the worst and it just feels condescending, even if it isn't meant to be. (Given how much I wrote up there eventually, imagine if the initial post were long enough to clarify a broad swath of what I have thought about or previously researched. TL;DR!)

Lifts are valid modes of transition too (and certainly more economical in floor space) and would be interested in precedents that use them well, especially in non-standard ways - I'm not only interested in ramps. But - after spending a couple of months in a building in which at least one of the elevators is perpetually broken or under repair, the ability to avoid relying on mechanical systems has its appeal.

In the examples AP posted, pretty cool. The main thing I can see as being problematic is actually the auditorium with the multicolored chairs. I would prefer to avoid seating (or doors, or sizes of rooms, or whatever) that dictate what size people should be... sizeism enacted through standardized chair dimensions is not my cup of tea either. I'd use a bench system (long continuous seating) or perhaps better yet, a modular system that allowed users to push seat units together into bigger or smaller chunks depending on # and size of people. This would also allow people to define their groups of friends, preserve personal space so some creep can't sit too close on the bench, possibly cram in more people on a crowded lecture, etc. & could still preserve the color-pixel design effect when the auditorium is empty.

Susan, discerning the likely precedents does actually matter because you can then better understand the design process. Momo most likely looked at the earlier Vatican ramp.

"There is a spiral 'staircase', designed by Bramante c. 1504, which allowed individuals on horseback access up to the Vatican's Belvedere Palace (which today comprises much of the Vatican Museum) from the street level several stories below."

It is not a stretch to connect horseback to automobile to wheelchair and their relation to ramps within architectural designs.

Wrights ramps (at the Guggenheim) are very evolved beasts.

ps

The Mercedes-Benz Museum is by UnStudio, not H&dM.

i hate to keep harping on this but that kunsthalle ramp don't meet ada either. the fact that when you deal with these issues over and over you begin to think in those terms. the first question you ask yourself is this fucker ada compliant? and maybe you can design ten different ramps with one being the ada compliant ramp. but when timmy goes over the edge of the ramp that doesn't comply, then you have problems.

Arrgh, another case of people totally not reading what I am actually saying. (If I thought that looking at precedents didn't matter, why would I post a thread... asking if anyone knew of some precedents?) I just meant that I don't really care if someone has "copied" a previous design (not problematic) or if it is an original technique.

& oops, my bad on the UN/HdM confusion. Sorrryyyyyy UNStudio.

And Susan, I too could say you missed the point because it wasn't "oh look, Wright copied!" rather look at what it was that Wright further reenacted. Momo's design is actually a quite modern people mover within architecture, as opposed to (first) a vehicular mover. And, since it's a double helix, there's even something universal about it.

here's a precedent. the romans in order to capture masada built ,or rather had there slaves build, ramps up the shear cliff sides to slaughter themselves some jewish rebels. who surprise already killed themselves.

SurfaceS:That said - since I am designing a building, I fail to see the problem with approaching this from the angle of building and landscape design

i personally don't see it as a problem, i just see it as being trivial. not trivial because its a trivial ambition or a trivial outcome but because as opposed to each one building having to tortuously conform to standards that never really address all disabilities anyway, the solution should be in the assisted evolution of the body to address all and any potential obstacle. by calling this exercise on the part of the architect trivial, I’m not implicitly claiming that the involved architect is not honorable or that this one edifice of hers does not make the world a better place, I hope you understand.

SurfaceS "There is also a contingent of disability rights activists who say their bodies do not have pathologies to be adapted/altered with technology/medicine..."

i also said:

relative to the future becoming of ourselves, we are all currently disabled and we will all be augmenting and removing features from our psychic-physiological selves.

that is to say, disability alters with the alteration of the denominator, the norm - and by person, i also include the sum of her parts, including those that would be added (whether mineral or biological), even by virtue of subtraction, should that be the case.

and concurrent would be the change in what constitutes natural and artificial. hence, i bring up the anxiety of authenticity and original-ity we exorcise into art.

the anxiety manifest in the domain art criticism concerning authorship and original-ity (a proxy anxiety over the authorship and original-ity of our selves in the galactic graveyard of a deceased god) might then manifest itself in the domain of medical ethics and human rights.

in spite of that, art has been created out of this very anxiety over art (prototypically, duchamp). therefore, inspite of this anxiety we have over what corporeally belongs, or rather is us (and this goes to address SurfaceS: is also a contingent of disability rights activists who say their bodies do not have pathologies to be adapted/altered with technology/medicine, but are deserving of acceptance, "eccentricities" and all.), the changes in our understanding of corporeality will be naturally(haha not) in synch with the growing space of virtuality in our life, with the increasing inorganicity of our daily lives. a caliber of abstraction that confounds the mineral with the organic. those disability rights activists are only basing their understanding of their disability on the traditional belief in corporeal originality in an age that is heading towards a complete en-abling of everyone else. i totally understand their nostalgia – and it is nostalgia- for a sacrosanct corporeality, but its clear this is not the physically secular future we're heading towards.

and there was a miniseries starring peter o'toole!

don't be offended, surfaces. this is all pretty tame compared to the responses you would get in a review. i think it's awesome that your background is in community activism and industrial design. that seems like the perfect combo for just the project you are working on, but instead of trying to "architecturalize" the project with an "interesting" section, i would use your background to second guess what the architecture actually is.

you're absolutely right about "universal" design which is why my criticism of the ramps in mccormick is unfair. those ramps do address a condition that makes access universal and should not be designed specifically for the disabled. BUT...from the jist of this thread, i was assuming that the point of your studio was designing for the disabled in which case the universal aspect perhaps is not as important as the specific user (a point you will need to take a clear stand on.) i have no doubt you have thought through these issues far more than i have as i type away on my lunch hour, but i'm just offering a different perspective for you to dimiss as you see fit.

or more pertinent, flesh-secular future.

yes this is it. trivial because its always about one instance of now

then this goes back to my issue with my guts and the deference of the present/the now. i don't know how to come to terms with the hollywoodish seemingly happy-go-lucky koan (more like a steely will with the optional addition of denial) to 'live each moments like its your last'. and i admit it, i'm scared. i don't understand how those blonde cocks arent fucking terrified.

INDEPENDENCE® iBOT® 4000

mobility system - invented by dean kamen (inventor of that segway thing)

FYI - the point of my studio is NOT design for the disabled. (It just has, at the very end of the program brief, as tacked on at the end of all of our program briefs because NCARB requires it, one sentence along the lines of "All student work must conform to ADA standards.") This is something I'm interested in working through in the broader context of the project, which is an arts and sciences university building. I think one should consider this regardless of WHAT one is designing, so I am. It's just one thing I'm thinking about, the one thing I'm choosing to discuss here - which, by the way, isn't even the conceptual underpinning of the project.

jafidler - I should also admit here that due to aforementioned "alternative" bacoground, I kind of also just want to learn to make a decent drawing for once, instead of a sad, unclear, butt-ugly drawing that makes the critics say nothing more about it than "um... you need to learn how to draw a section." Hahaha. I can't help but second-guess the more typical architecture pedagogy, and while I like doing that, I don't think it is inherently productive. At some point I do want to step back and, in a way, second-guess my own tendency to second-guess. I think my critic has asked me to think about it differently than I have been because he thinks I would benefit/learn from spending time on this approach and I can accept that. & I know that I can improve my drawing within any conceptual framework too. OK, that is my personal architecture TMI.

vado - Kunsthalle is not even in the A (of the Americans with Disabilities Act) - I guess they can deal with their own standards.

I don't think it's entirely this simple, not at all. But there seems to be a line of thought in disability activism that holds, basically, that if more architects (and product designers, and others...) had committed to at least attempting UD once it was pointed out to them that multi-levels and stairs and curbs don't work for many people, it wouldn't have been necessary to institute such a labyrinthine set of codes to legally force architects & planners extremely prescriptive ways of doing so simply because they're total dismissive jerks about disability otherwise.

I get the sense that some of the stringency of ADA regs is not due only to actual safety concerns, nor even governmental bureaucracy and tendency to simplify/standardize things - but largely comes from the assumption that most architects/planners/etc. fundamentally don't care about disabled people's needs, at least not enough to address them without being legally obligated. And therefore disability advocates insist upon extremely stringent/prescriptive regulations in order to protect themselves, and this regulation (and activism) has elements of antagonistic/hostile undercurrents toward architectural design.

I mean stuff like this, from the article posted from Metropolis:

For most of my life I have had a love-hate relationship with architecture and architects. It has generally been my experience that the making of physical spaces to welcome people in wheelchairs has ranked on the low end of the scale of importance for most architects, down there with selecting the paint for a stairwell. Accessibility is fine for ugly strip malls in Texas but somehow eludes the stair-encrusted Four Seasons Hotel in Man-hattan. Universal design seems like more of an architectural afterthought than a central tenet of building, even today.

Given that, I really cannot see a problem with trying to sort out working approaches in general, not merely ADA-complaint ones. Alternatives, including designs like the OMA Kunsthalle which has its proving ground outside of the jurisdiction of the ADA, might even eventually become accepted into ADA standards after some lobbying and so on.

Howski - Momo = FLW? (sorry, just have never heard that nickname.)