When Habitat 67 was first unveiled to the world almost six decades ago, it changed the landscape not only of Montreal, Canada, but of architectural discourse on how modern buildings could be designed, constructed, and lived in. The structure also catapulted its young architect, Moshe Safdie, to a global architectural stage that he still holds today.

The acclaim won by Safdie and his pioneering residential scheme is made all the more remarkable by the fact that the Habitat 67 we know today is only a fragment of a much more ambitious community that was never realized.

Decades later, a team led by Safdie Architects, Epic Games, and Neoscape collaborated to recreate the original intention of Habitat 67 in the hyper-immersive Unreal Engine visualization software. Below, we retell the story of how the so-called Project Hillside came to be, with perspectives from Safdie Architects Senior Partner Jaron Lubin.

This feature article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Visualization series.

In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, Epic Games’ Carlos Cristerna reached out to his friend Jaron Lubin, a Senior Partner at Safdie Architects. Cristerna and Lubin had known each other for years, owing to Cristerna’s previous role as a director of the creative agency Neoscape with whom Safdie Architects had often collaborated.

In his new position as a Senior Product Specialist at Epic Games, Cristerna had an ambitious proposal for Lubin and Safdie Architects. Under the plans, Epic would take an unbuilt Safdie Architects project and recreate it in Unreal Engine to push the technological limits of the program’s capabilities, reaching beyond the illustrative and descriptive toward complete environmental and atmospheric immersion.

Cristerna asked Lubin what project they should tackle. “It was a no-brainer,” Lubin recalled in a recent conversation with me. “Take the original, unbuilt Habitat 67.”

Habitat 67 had prior experience in pushing limits. The origins of the project can be traced back to Moshe Safdie’s master's thesis at McGill University where, before embarking on his final year of studies, 21-year-old Safdie was awarded a scholarship in 1959 to travel across North America to study housing typologies of all descriptions: high-rise to low-rise, urban to suburban, dense to sprawling, affordable to luxurious.

“Touring these projects was soul-crushing,” Safdie recalls in his 2022 book If Walls Could Speak: My Life in Architecture. Housing in urban areas, whether public housing or luxury developments, seemed cage-like and divorced from the ground below. Meanwhile, the suburban developments, which many were drawn to as an escape from the stress of the city, consumed too much land, energy, and transportation.

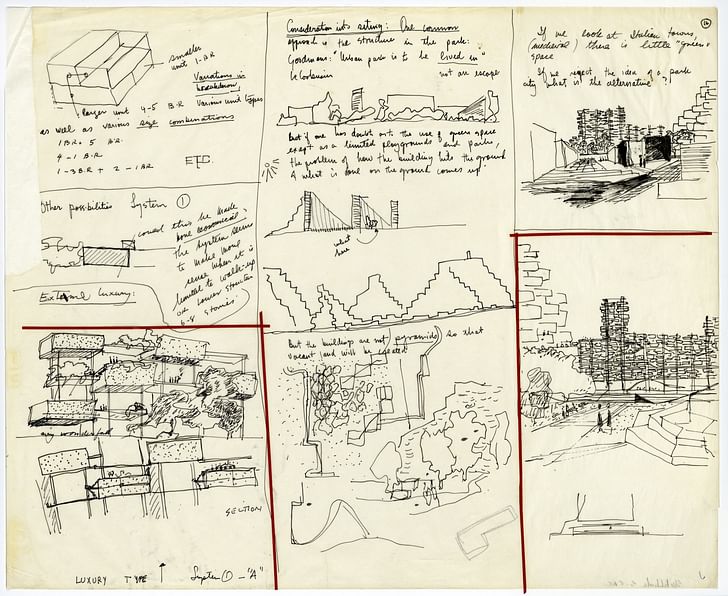

“By the time I returned to McGill, I knew what I wanted my thesis to be,” Safdie’s book continues. “I wanted to describe why suburbs are seen as desirable but also what they failed to achieve; and why apartment buildings are hated, even as they seek to resolve the inescapable challenge of urban density. The challenge I posed was how to provide the quality of life of a suburban house with its garden but do so in a high-rise structure.”

I realize today how radical my thesis must have appeared. — Moshe Safdie

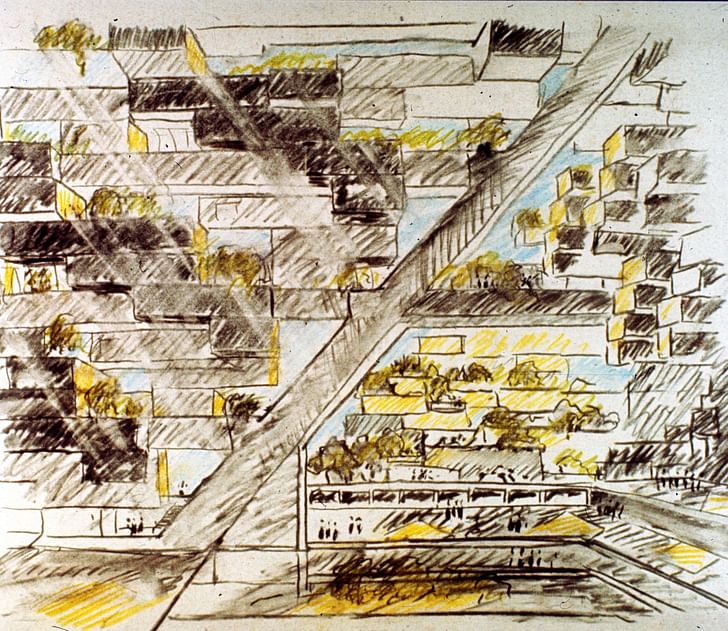

Safdie’s resulting thesis, titled ‘A Case for City Living,’ comprised a housing system whose three principal approaches could be deployed and adapted for any location.

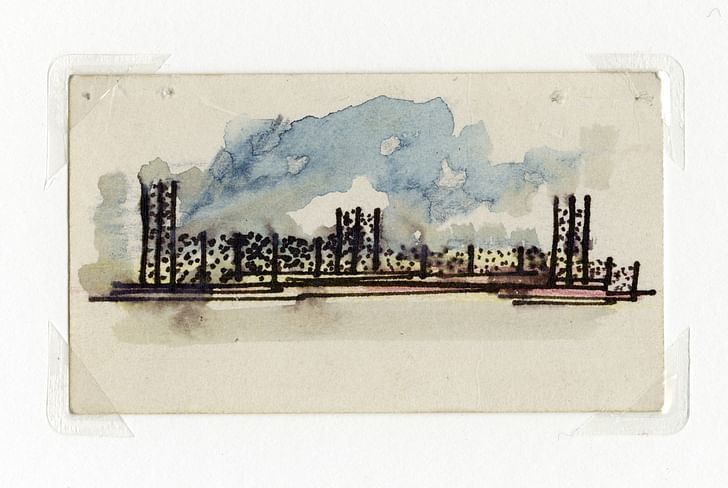

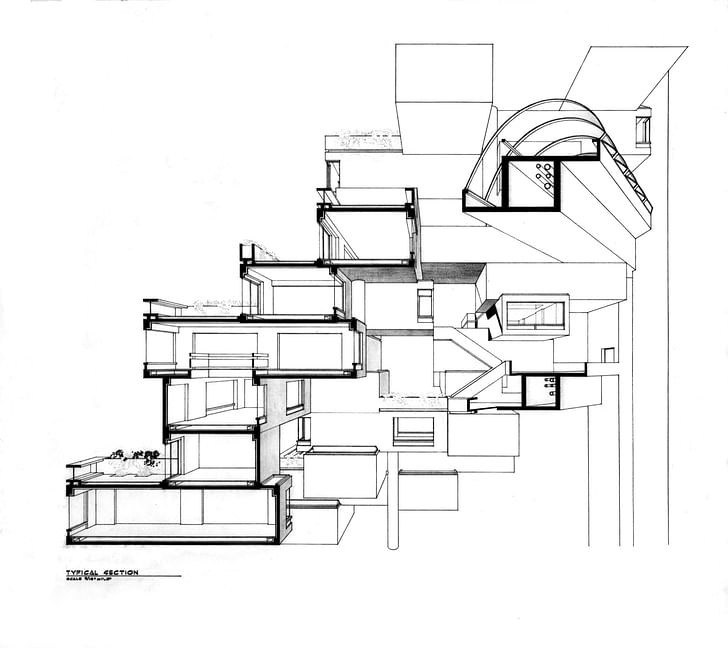

The first approach, covering buildings between 20 and 40 stories, consisted of a framed structure in which box-like living units could be inserted in a spiral formation, with each unit gaining a garden atop the roof of the unit beneath. The second approach, for low-rise structures, was similar to the first but without the supporting frame, meaning each unit structurally supported one another. The third approach consisted of prefabricated walls that shifted at 90-degree angles from floor to floor, set back to allow open gardens for each townhouse-like unit. For all three approaches, Safdie’s commitment to providing each unit with private outdoor space was captured by his principle of ‘For Everyone a Garden.’

“There was a certain amount of mystification in the school about what I was doing — about what a ‘system’ was,” Safdie recalled. “Everybody else was designing museums and opera houses and libraries for their theses. […] McGill submitted my thesis that year as its nominee for a special prize for best academic thesis — every Canadian school could submit one candidate — and it must have landed with a thud. The prize was won that year by a design for an opera house in Toronto. I realize today how radical my thesis must have appeared.”

Years later, in early 1963, while working as a recent graduate at the office of renowned architect Louis Kahn in Philadelphia, Safdie was offered the unexpected opportunity to lead the design of a master plan for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition, commonly known as Expo 67, in Montreal. In addition to overseeing the overall Expo master plan, Safdie was tasked with developing the ideas from ‘A Case for City Living’ into a realized project within the master plan, soon given the title Habitat 67.

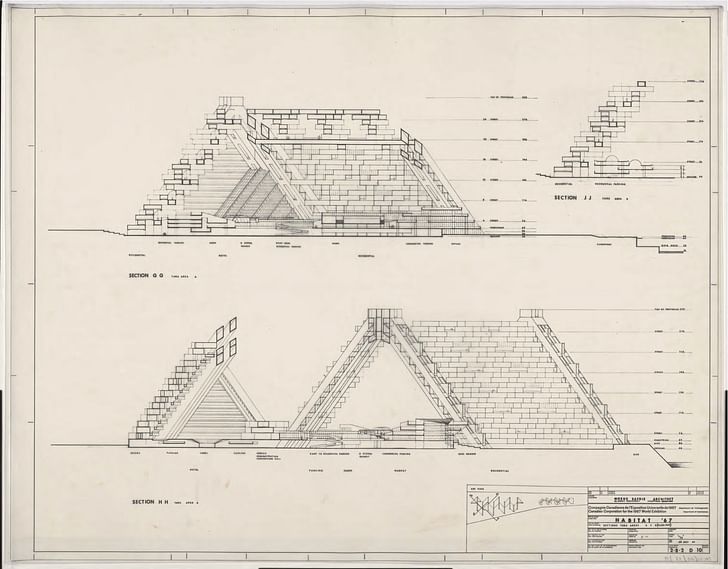

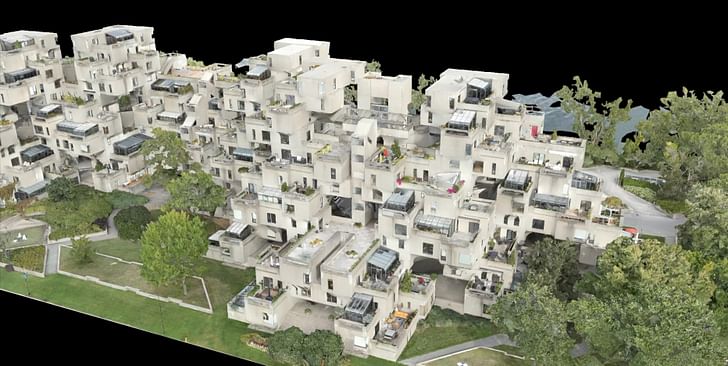

The vision for Habitat 67 was for an urban sector occupying Mackay Pier, a peninsula of land that would be artificially enlarged to accommodate the project. In contrast to the vertical towers of Safdie’s thesis, Habitat 67 would take the form of a hillside: Slopes of stacked housing units stepping back floor by floor to create gardens on every level, all supported by A-frame structures to stabilize the massing. Beneath the hillside would be sheltered public spaces, community facilities, schools, shopping, and workplaces, while ‘streets’ would be laced across the project every four floors. At one end of the structure, towards the pier, would be a smaller twelve-story-high cluster of units, similar to the second approach to massing outlined in Safdie’s university thesis. In total, Habitat 67 would hold 1200 dwellings, which would continue to serve their function long after Expo 67 had concluded.

Safdie’s original proposal for Habitat 67 overcame many obstacles in the lead-up to the expo. Sand was dredged around the clock to create the new landmass required for the project, while an upstream ‘ice bridge’ was constructed to break up ice flowing down the St. Lawrence River. Safdie’s vision for the wider expo navigated three levels of government funding, while his proposals for both Expo 67 and Habitat 67 saw off unexpected challenges by rival schemes. Despite surviving such obstacles, budget realities ultimately demanded that Habitat 67 be significantly scaled back.

“I was in shock for a day or so, convinced that the last chapter of the Habitat story had been written: The dream would remain a dream,” Safdie writes in his 2022 book, reflecting on his reaction to the news that funding had been reduced from the original $42 million down to $15 million. “Then I started asking myself: What might we do with $15 million?”

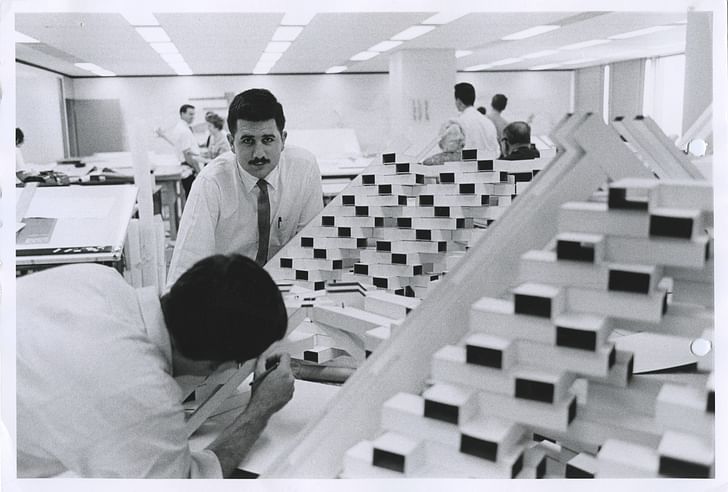

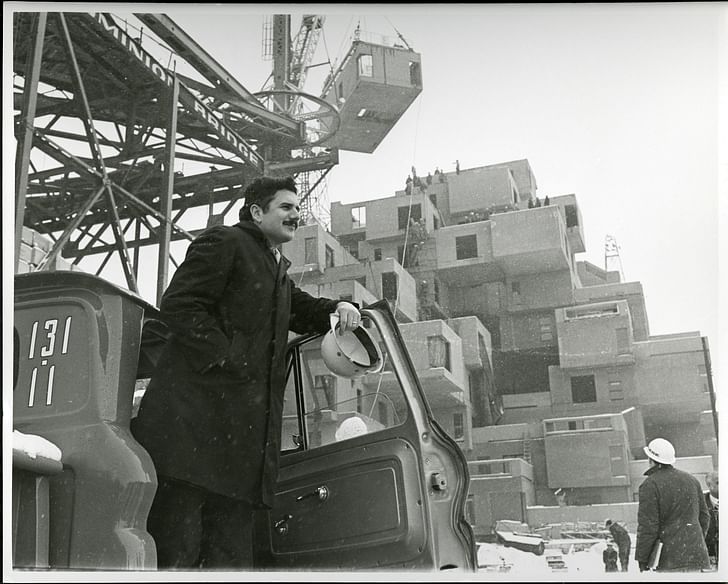

As it turned out, $15 million could create an icon. With the larger urban sector not feasible, Safdie’s team constructed the twelve-story village of self-supporting dwellings intended to sit at the tip of the peninsula. In total, 354 prefabricated modules were arranged in three clusters to create 158 residences, with elevated ‘flying streets’ providing access across the development.

“There was a lesson in this, one that I’ve found myself remembering throughout my career,” Safdie’s reflection continued. “Sudden duress doesn’t have to mean the end of the story — sometimes it gives you the material for a different story.”

The realized version of Habitat 67 retold the story of how urban housing could be assembled and experienced. Each module was cast in a factory operating on the site, fully equipped with doors, windows, plumbing, wiring, bathrooms, and kitchens, before being lifted by crane onto its allotted space on the larger structure. Meanwhile, a new economy formed around the project’s construction, with product and appliance manufacturers commissioned to design bespoke fixtures and fittings for the interiors.

The realized version of Habitat 67 retold the story of how urban housing could be assembled and experienced.

Following the expo’s conclusion at the end of 1967, Habitat 67 rebelled against the tendency for expo pavilions to be dismantled after a short life as a demonstrative showpiece and instead saw permanent residents move in. Today, the complex continues to serve its original residential purpose.

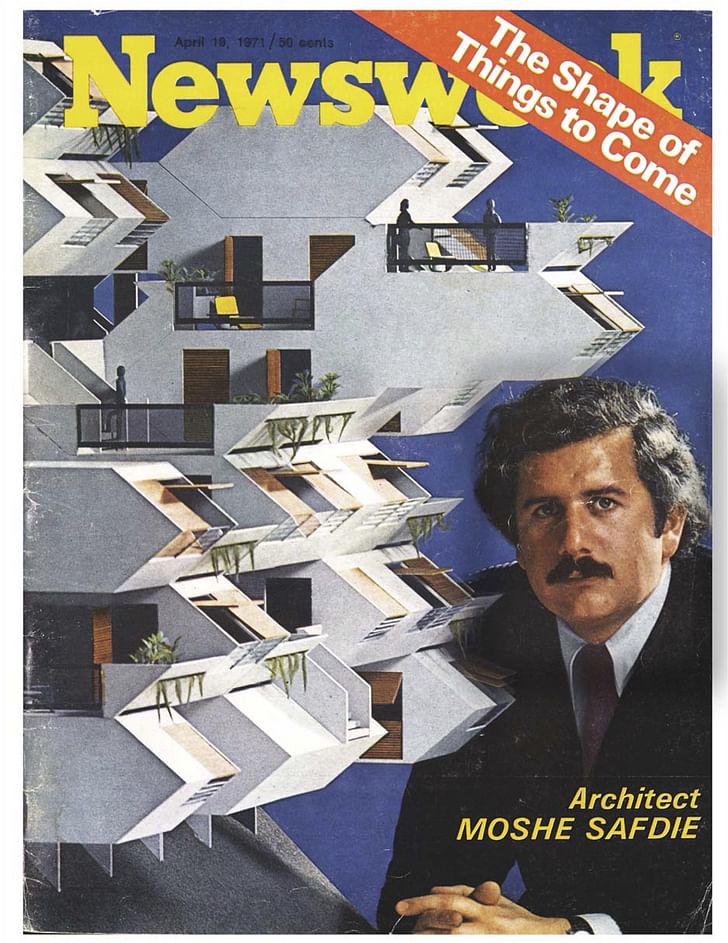

“The press coverage of Habitat 67 was, to me, astonishing,” Safdie writes in If Walls Could Speak. “It seemed to encompass every newspaper, magazine, and TV program in North America (and beyond), culminating with a cover story in Newsweek.” Meanwhile, The New York Times’ architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable described the scheme as “a significant and stunning exercise in experimental housing” and a promise of things to come.

Despite its seismic and continued impact on architectural discourse, the Habitat 67 we know today is itself a promise only partly fulfilled. With the realized scheme holding less than a quarter of the dwellings imagined in the original design, one cannot help but wonder how the world would have reacted if Habitat 67 had been delivered in its entirety; how it would have altered not only the landscape of Mackay Pier and Montreal but of attitudes to city living and urban planning. Six decades later, Cristerna and Lubin would make it their mission to find out.

In our November 2024 conversation, Lubin offered an insight into how his team at Safdie Architects brought the original Habitat 67 to life. “We assigned a team like we do on any project,” Lubin recalled, who would work with Cristerna’s current team at Epic Games and previous colleagues at Neoscape to translate archived schematic drawings of Safdie’s vision into a detailed, immersive, virtual experience dubbed 'Project Hillside.'

“The early stages were exactly the same as a conceptual project,” Lubin continued. “Moshe and I would sit with the team and serve as critics, giving prompts to figure out what the appropriate design would be.”

While staying faithful to the original design of Habitat 67 as it existed in archival drawings, the team behind Project Hillside was faced with a series of design decisions to bring a resolved project to life. As the original scheme was not accompanied by a surrounding landscape design, Lubin’s team was tasked with transporting themselves back in time, imagining what would have been.

“We imagined a collaboration with Dan Kiley, the noted, wonderful landscape architect who was transformative to the landscape industry,” Lubin told me. “So we were designing in the spirit of a landscape architect that we probably would've collaborated with.”

Inside the apartment units, meanwhile, the team sought a similar balance between faithfulness and modernization. “The only place you would recognize changes are in the kitchen and bathroom,” Lubin told me, explaining the mindset of ‘timeless value’ that underscored the team’s approach. “Moshe would joke that were you to use AI to alter the original photographs of Habitat 67 being constructed, and showed contemporary cars parked on the site, you wouldn’t know that it wasn’t being built right now.”

There are now so many buildings that fit within the universe of geometry, of language, of architectural heritage, of the archive, and of our own sensibility. — Jaron Lubin, Safdie Architects

While the residential units modeled for Project Hillside could draw on their counterparts in the realized Habitat 67, Lubin’s team was faced with more fundamental design decisions when it came to modeling the original scheme’s mixed-use district. As noted above, the original Habitat 67 called for a sheltered network of community facilities, schools, shopping, hospitality, and workplaces, much of which was not designed in detail, and was never constructed in the real world. Lubin’s team therefore picked up where a young Safdie had left off.

“It was a lot of fun to design a school in the spirit of the space,” Lubin told me. “When you walk around [in the model], there are now so many buildings that fit within the universe of geometry, of language, of architectural heritage, of the archive, and of our own sensibility. But we had to design them.”

While Moshe Safdie remained hands-on and involved in the new decisions, Lubin’s team still managed to leave small, hidden surprises in various parts of the scheme. “When we showed him the first cut of the film, he got emotional,” Lubin recalled. “He said it was exactly how he had imagined the project. It was like we gave him a gift. It was really a wonderful day.”

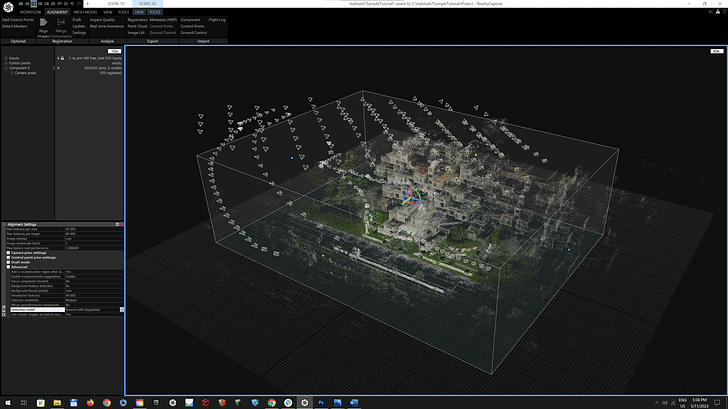

While evolving and resolving the original design of Habitat 67 was a core component of Project Hillside, the undertaking was equally driven by Cristerna and Epic Games’ desire to push technological limits. With Lubin’s team at Safdie Architects undertaking a complex design development process, Cristerna’s former colleagues at Neoscape set about mapping the existing structure.

Above Habitat 67, one drone equipped with a camera and LiDar flew a pre-programmed path around the development, while a second drone captured over 4,000 high-resolution images mapping the scheme’s structural details. The result was an accurate, detailed 3D model of the existing project that, in addition to supporting the team’s visualization efforts, preserves the existing state of Habitat 67 as a digital archive for future students.

As Lubin’s team resolved the scheme’s final design, Project Hillside manifested in the form of a 3D model built in Rhino and 3ds Max before being imported into Unreal Engine 5. The basic import was then populated with elements such as trees and plants and set against the backdrop of Montreal. In total, more than 4.5 billion triangular polygons were used to create the virtual environment.

While in Unreal Engine, the team also took advantage of Lumen, Unreal's global illumination and reflection system, to give the project a realistic, atmospheric aura. Aided by the software’s real-time rendering function, the model was analyzed in live team reviews and edited to optimize lighting conditions, material finishes, and animations.

“It is delivered for all seasons, for all hours,” Lubin told me. “It simultaneously has the intelligence of every time and every place all at once. The atmospherics of the final film, such as rain and lightning storms, is a subtle nod to the idea that this model can be tuned to show what it will feel like on any second of any day.”

The completed Project Hillside shares intriguing similarities with its physical counterpart; ones that reach beyond their shared architectural blueprints. Just as Habitat 67 was born out of a desire to push technological boundaries in the pursuit of transforming urban living, Project Hillside was likewise born out of a desire to push technological boundaries in the pursuit of transforming how one perceives the built environment.

Moreover, just as Habitat 67 reached beyond its initial showcase as part of Expo 67 to become a longstanding fixture of Montreal’s urban fabric, the team behind Project Hillside believes their creation’s longevity will extend far beyond its initial use as a showcase of visualization software. In that spirit, the finished model of Project Hillside has been made available for anybody to explore, build upon, and learn from.

“This is exactly what we need to rethink how our cities are made,” Moshe Safdie said during the public release of the model in 2023. “I hope that making this model accessible to the public at large and the idea that you could live somewhere like Habitat 67 helps advance people's desire to have this realized.”

“We encourage people to take these pieces and come up with their own ideas,” Cristerna added. “Design your own habitats, have fun with it, learn from it, make your own movies and renders, practice your craft.”

Meanwhile, as our conversation drew to a close, I asked Lubin if the exercise of revisiting and evolving the original Habitat 67 had caused him and his colleagues at Safdie Architects to see the project in a new light.

“Absolutely,” Lubin replied. “There is nothing like being able to inhabit the space the way that we did and experience the scale. When you navigate the space, even on the computer screen, you can really feel it.”

“When we delivered that model, everyone was talking about it,” Lubin added. “The ability to look back and investigate [Habitat 67] has put it fresh in our minds again. We are just waiting for the opportunity and the circumstances to make it real.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.