Fifty years ago, a young Canadian-Israeli architect got the chance of a lifetime: the opportunity to realize his senior thesis for the 1967 World Fair in Montréal. The resulting housing complex inspired generations of architects inside and outside of Canada, and its influence is visible in buildings built to this day. It wasn’t just formal innovation that determined Habitat 67’s significance—although that’s certainly part of it—but also the new way of life it imagined by way of affordable, dense urban housing with all the greenery, spaciousness, and privacy of the suburbs.

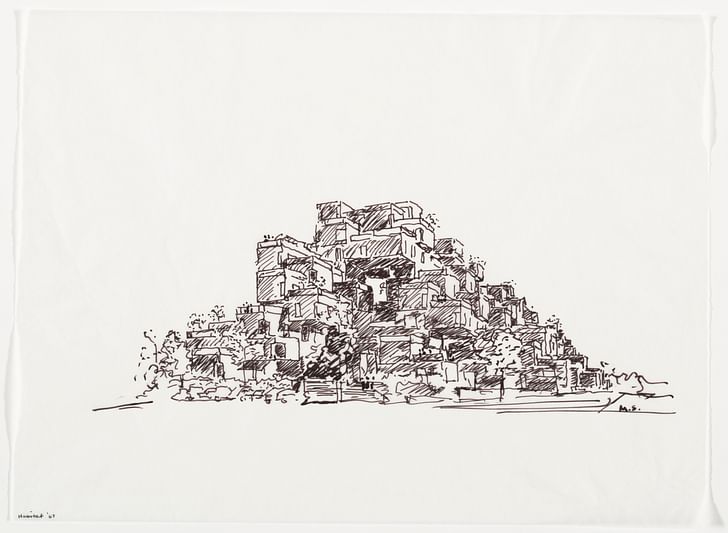

The architect was, of course, Moshe Safdie, who has since had an illustrious career building around the world. Situated on the Marc-Drouin Quay, a peninsula jutting out into the Saint Lawrence River, Habitat 67 (or just Habitat, for short) stands out. It’s constructed from pre-fabricated, modular forms stacked on top of one another and resembles, to the post-digital eye at least, a long mass of pixels. Each unit has at least one private terrace—an amenity now so common in urban housing design that it’s almost mandatory, but which was nearly non-existent at the time. Although intended as affordable housing, its popularity quickly brought up prices. A major symbol of Expo 67, which focused in part on housing, Habitat was visited by over 50 million people the year it opened.

To mark the anniversary of this landmark of post-war modernism, I spoke with Safdie about Habitat’s beginnings, its place within the rest of his oeuvre, and the status of his practice today.

It’s the 50th anniversary of Habitat 67 this year.

Hard to believe.

I know that the building was an adaptation of your thesis, but I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about its origins and the ideas propelling your thoughts at the time?

As a student I had the good fortune, in the year before my last, to get a traveling scholarship that the Federal Housing Authority of Canada created where they take one student from every school of architecture in Canada and have them travel together to study housing across the continent. We spent the summer looking at suburbs, public housing, and all kinds of housing across the entire continent—the United States and Canada. When I got back, I said: that’s going to be my thesis.

Although it was an undergraduate degree, we had thesis requirements. I called it, “A Case for City Living.” I outlined in words and diagrams how we might go about rethinking the traditional apartment building, which was then manifest in public housing and private housing—the heroes of that time in Detroit and Montreal and wherever. So, I formulated it as a series of questions, which, then, during my thesis, developed into a number of schemes. The overall [motivation] was for everyone to have a garden, and I developed a mid-rise/high-rise series of modular prefabricated housing, all of which tried to provide a garden for every unit and open up the circulation to the streets and the air. That was well-received and published. It was actually published by Aldo van Eyck in the Dutch magazine Forum, which was, for young graduating students, amazing. Then, I went to work for [Louis] Kahn.

It was a fairy tale. I hadn’t built a building at that time.

As I was there, in 1962, my thesis advisor [Sandy] van Ginkel shows up and says, “We are going to have a World Fair and I want you to come and do the masterplan for the World’s Fair and head the whole team.” I said, “Okay, I will come back but I have one condition”—this was in a civil service position as that was a government corporation—“I’d like permission to develop my thesis to be one of the central themed pavilions of the World’s Fair.” To this he said, “As long as you do it on your own time, you are welcome to do it and we will give you the resources.” That was the opportunity.

Then, I got back and we developed the masterplan that Expo was built around. They gave me a grant that they received from the cement companies—$50,000, which was then a lot of money. It sounds like a joke now but it was a lot of money and I hired [August] Komendant, who was a great concrete engineer that I knew from Kahn’s office. We developed the scheme and adapted it to the site and developed engineering and cost estimates. Expo management loved it and told us to go to Ottawa and present it to the cabinet. They didn’t approve the whole thing because the original was 1,000 units and covered the entire peninsula. They said they’d give us a limited budget of $17 million and for us to build as much as we could, which ended up as the project we built.

It was a fairy tale. I hadn’t built a building at that time. When they did approve it, they told me I should resign and open my own office, as it was my idea and I shouldn’t do it within a government office. That was also the birth of my office.

How old were you at the time?

I was 25.

Wow, that’s insane!

It was insane, and they were very courageous, I have to say. When I see the films of my interviews at the time, I look like a kid.

How would you say it changed the course of your career? Obviously, it was the start of your office…

It was complex because, without question,—50 million visitors and the cover of Newsweek—you’re on the world map. At the same time, for the first few years, there were several commissions for Habitats elsewhere. It was a bit like, many years later when Frank [Gehry] did the [Guggenheim] Bilbao, he got all these requests for people who wanted to build. So, I was getting all these commissions to do Habitats but none of them, for one reason or another, were getting built. I would do detailed drawings, detailed engineering, and spend months and months on them and they still wouldn’t get built. That was one very frustrating thing for several years. The other funny thing was I never [again] got a Canadian commission until I came to Harvard to teach in 1978. I was almost feared, or blacklisted, at the time, where people just wouldn’t commission me. There was a tough period of no work in Canada and all these other projects in different countries were not getting realized. In time it led to a shift because I started doing cultural buildings. The first series were Canadian projects which I had won competitions for after moving to Boston—I was almost feared, or blacklisted, at the time, where people just wouldn’t commission me.the Quebec Museum, the National Gallery of Canada, the Ottawa City Hall, the Vancouver Public Library. All were completed in the mid 1980’s and then the American projects followed. For two decades, I was doing cultural buildings almost exclusively. There was no opportunity for housing or mixed use. My first major mixed-use project was Columbus Center in the mid-80s which you probably know the story of…do you?

Please tell, I’m not sure I do.

We won the competition together with Boston Properties. The Salomon Brothers were going to be moving their headquarters to what is now the AOL Building. This was a 75-story, mixed-use residential, office, hotel, and shopping center. All hell broke loose—being attacked by the Times, which was then [Paul] Goldberger, for the architecture; and the Municipal Art Society, for the shadow over the park. I had a New York office, which started construction, and then the market crashed and the Salomon Brothers withdrew saying they couldn’t move out of Wall Street. It came to an end in 1986. That was an independently disappointing event in my life. I frankly enjoyed doing cultural buildings and then things got very hot in Asia after I built the Marina Bay Sands. Now, 80% of my work is there and it is mostly housing, mixed-use and development projects rather than cultural institutions.

Do you find there is a continuity between your early work in social housing like Habitat 67 and projects like Marina Bay Sands in Singapore?

I think Marina Bay Sands was highly specialized and there was interest in creating public open spaces in this particular case. There are no private open spaces but public open spaces such as the sky park and the roof gardens. Obviously, in some way, it goes back to Habitat. But it’s really the projects after that—the Bishan Sky Habitat housing complex in Singapore, the Qinhuangdao project in China, and projects currently under construction in Colombo, Sri Lanka and Chongqing, China—that really go back and draw on Habitat. Terracing public open spaces with private gardens and all that. None of them are pre-fabricated, or technologically in that direction, and, anyways, I think technology has shifted in terms of emphasis on pre-fabrication. These were much more [like Habitat] than Marina Bay. Marina Bay was a door opener. More people know about it then they do Habitat 67 in Asia. It’s a common knowledge-type building which opened up a lot of opportunities in Asia.

Would you say you maintain a social agenda with these works?

Absolutely. I think I maintain a social agenda in all my work including my institutional work—certainly in my housing. It’s true that some of what I do is super-luxury housing, but Sky Habitat is middle-income housing on the outskirts of Singapore and Qinhuangdao is middle-income, really, for China in the coastal cities. I have been involved over the years with Senegal, where I designed a city, and then one in Israel, where I controlled the development for 25 years as well as the urban design guidelines—and built a town center! In my work in Israel, I had many opportunities over the years, particularly with the new city. I was sort of the tsar of the city for 20 years and now there is a mayor and 100,000 people. Democracy and he have kicked me out and taken over and that is okay. I guess that is success.

I think I maintain a social agenda in all my work

I’m wondering, when you started working in Asian markets, specifically in Singapore, was there a learning curve? What kind of cultural differences, if any, did you notice?

Not really, because I first became involved with Singapore in the late ‘70s. I did three residential complexes, actually, in the ‘80s. One was Ardmore Habitat, in the spirit of Habitat, but in the formation of a vertical tower. It was more akin to what Herzog & de Meuron are kind of mimicking in some of their towers now. Another project was called The Edge. There, I explored doing some very small footprint towers that are bridging between each other—trying to develop a new typology.

So I knew Singapore well from these projects and then I had been advising the housing development board on how to break away from their stereotypical new towns over the years. In the Harvard framework, I did a big theoretical project of designing one of the new towns as an academic project. So I knew Singapore well when that happened. Actually, my client—the developer Las Vegas Sands—hired me over his admiration for the Holocaust Museum. He didn’t even know I knew Singapore. But that was a very hard [competition], which happily we won in this case.

Actually, Columbus Center, I should emphasize, was won in a competition as well. There were 13 entries and 13 developers at the time. I worked with Boston Properties and it was one of the big competitions of the ‘80s, developer/architect competitions. Isn’t it amazing to have been in practice for 50 years and you’re still still doing mostly competitions?

Speaking of your profession and your practice, your offices remain rather small, about 100 people. Is that correct?

Yes.

Despite having these really enormous projects. What’s the dynamic like in the office and how do you see your role as the lead?

I am involved in every project, which explains its size. I have to do that efficiently in order to be able to do that. I am involved in every project through every phase, meaning I’m involved with the early design, overseeing the detailing and working drawings—which I enjoy a lot—mock-ups, etc. and, then, I spend a lot of time on the site of every project. This means a lot of travel—but I feel some of the most important architectural decisions are made on the site, both with the mock-ups and sometimes observing and learning things as you build. My involvement is unusual because, at the same time, there is no way I could do that without a very capable and imaginative, creative, and compact team. And if I were to say how I think my office differs from some other large design offices, [it’s that] we have a big core. My peers have much bigger offices sometimes and there is always the coming and going of young architects and interns, but many people have been here 20, 30 years. When I say big core, I would say it’s about half of the team that has been a part of [Safdie Architects] for decades or at least ten years. The level of coordination and communication is formidable and that enables me, even as I travel, to stay in contact with every team. We usually organize a team with one design principle and someone managing it… A dedicated team that will see it through all phases. We don’t specialize departmentally between the phases such as construction and construction administration.

We never take a job where we don’t have full supervision until the end

Another thing, we have devised a very novel method of collaborating with local offices that are always necessary in this line of work, in a way that makes the effort seamless. We bring their design and technical people to our office for long periods during the design where they immerse themselves in the process and understand why and how decisions are made. Then we plant one, two, or three—in the case of Marina Bay Sands, it was 15 people in their offices—through the life of the job while it is being built. We overlap people in the phases and we stay in control until the end. We never take a job where we don’t have full supervision until the end, which means you give up a lot of Asian work, where they ask you to deliver a drawing and leave in them in peace thereafter. That was 20 years ago and at this point I think I’m lucky that my energy level hasn’t adjusted.

What’s the future of Safdie Architects?

At this point, it is full steam as we always did. But, also at this point, I have made a select group of my most experienced and trusted people equity owners. There is a team now that is committed to its future as I leave the scene. I think because the practice is not personally idiosyncratic, if I can put it that way, much of our design process is extremely open and discussed. It follows a certain logic and principles and there’s a lot of consistency in that. I hope they continue the practice and realize the work that’s in process and take on new challenges. We are doing projects right now that probably have a 7-8 year life.

Thanks Moshe.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

4 Comments

This is so awesome!

Great architect with rightfully earned respect. I would like to see his office playing a more active and constructive role working with Palestinian communities in West Bank. Projects that really benefit them. With his influance and humanitarianism, he can help solve some extreme gentrification issues in Jerusalem neighborhoods, especially in Palestinian areas. This is one area he could address effectively.

Agreed, one of the real greats, and under-recognized. Substance that is largely missing from the work of more awarded names.

Interesting to hear his thoughts on succession "I have made a select group of my most experienced and trusted people equity owners. There is a team now that is committed to its future as I leave the scene. I think because the practice is not personally idiosyncratic..." There and earlier in the conversation he seems clear that he views authorship as shared across a "big core" and the firm is not a "personified" Starchitecture...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.