Before the invention of architectural perspective, architects and artists faced significant challenges in visualizing and communicating architectural space. Without a systematic way to represent depth and spatial relationships, architectural drawings were often symbolic, schematic, or abstract rather than realistic.

From ancient times through the Middle Ages, the ability to convey three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional medium, representing space in a manner satisfactory to the human eye, eluded even the most advanced societies and civilizations — at least, as far as historians know.

Then, in Renaissance Italy, a solution emerged that would change the field of architectural visualization, and of architecture, forever.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Visualization series.

Before the advent of perspective, architectural visualization was rather flat. Those seeking to communicate architectural proposals relied on orthographic projections, diagrams, and rudimentary sketches to represent buildings; methods that, though functional, did not satisfactorily reflect the way the human eye perceives architectural space.

History’s earliest architectural drawings, such as those found in Saudi Arabia and Jordan dating to 9,000 years ago, were therefore largely schematic. Sketches and engravings conveyed information about a building’s design but were abstract and two-dimensional. More broadly, the study of ancient architectural representation in drawings has proven to be difficult for historians, with limited records or understanding of how even advanced ancient civilizations depicted unbuilt works.

In ancient Egypt, for instance, research suggests that architects and artists were more concerned with the depiction of existing structures rather than proposed works. Elsewhere, eight drawings originally attached to Vitruvius’ De architectura, which intended to demonstrate how both the ancient Greeks and Romans undertook draughtsmanship, have since been lost to history.

Medieval art was characterized by a hierarchical scale, where the size of figures and buildings was determined by their spiritual or social importance rather than their physical distance from the viewer.

In the centuries leading up to the Renaissance, the inability to offer a realistic three-dimensional depiction of architectural space on two-dimensional planes persisted. Medieval art was characterized by a hierarchical scale, where the size of figures and buildings was determined by their spiritual or social importance rather than their physical distance from the viewer, or the categorization of objects in paintings into three ‘planes’ depending on their importance. As a result, compositions appeared flat and lacked realistic depth.

While the Middle Ages did not yield significant advances in how to perceive three-dimensional space through a two-dimensional medium, progress was nonetheless made in other areas of architectural representation. As Archinect has previously reported, new research from the University of Aberdeen suggests that a 12th-century Scottish monk in Paris may have been the first to devise a complete set of architectural drawings as we would recognize such a set today: including several plans, elevations, and sections.

By the Middle Ages, therefore, the viewer could analyze a collection of interdependent orthographic drawings to gain an understanding of the geometries of unbuilt architectural space. However, the ability to fully communicate a building’s spatial character, in three dimensions, in a single drawing, remained unfulfilled. In the 15th century, this would change.

The Renaissance, particularly in Italy, marked a profound shift in the way architecture was both designed and represented. The central figure in this shift was the architect and artist Filippo Brunelleschi, who readers of Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence will have met owed to his design of the Duomo in Florence and the many design and construction innovations it heralded.

In approximately 1415, Brunelleschi transformed architectural visualization by introducing a method to depict space in a realistic manner, today known as ‘linear perspective.’ Brunelleschi's experiment involved painting existing buildings using a mathematical system that accurately represented how the structure would appear to an observer from a fixed viewpoint. The breakthrough allowed artists and architects, for the first recorded time, to represent architectural space in a way that resembled human vision.

Brunelleschi’s method relied on the principle that parallel lines appear to converge as they recede into the distance, meeting at a single point called the “vanishing point.” In a one-point perspective, the vanishing point is positioned on the horizon line, directly in front of the viewer. All horizontal lines in the scene converge toward this point, while vertical and perpendicular lines remain straight.

Two-point perspective, meanwhile, uses two vanishing points, typically placed on the horizon line to the left and right. While the one-point perspective excels in drawings where the object faces the viewer head-on, such as a hallway or facade, the two-point perspective is effective for visualizing objects viewed at an angle, such as a corner of a building.

The breakthrough allowed artists and architects, for the first recorded time, to represent architectural space in a way that resembled human vision.

Approximately two decades after Brunelleschi’s breakthrough, architect and humanist Leon Battista Alberti would codify the principles of perspective in his 1435 treatise De pictura (On Painting). Under the influence of the writings of Roman architect Vitruvius, Alberti would further expand on the applicability of perspective drawing to architectural visualization through his book De re aedificatoria, emphasizing the importance of geometry and proportion in achieving a realistic depiction of space.

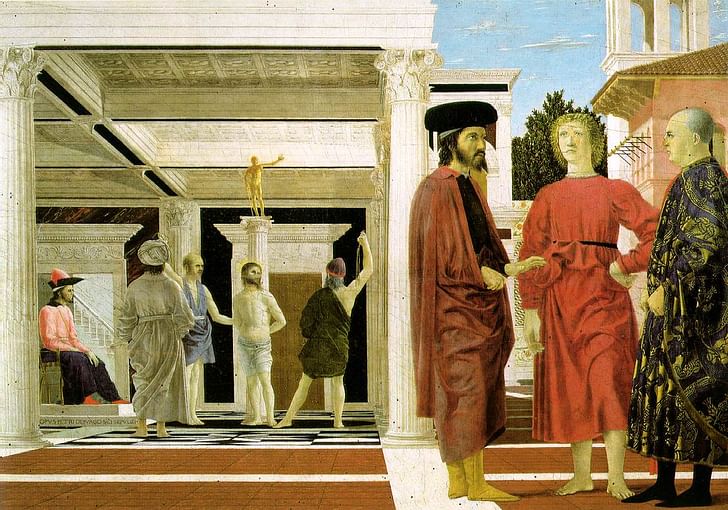

Brunelleschi’s observations, and Alberti’s codifications, would continue to be built upon in succeeding generations of architects and artists. Piero della Francesca, a contemporary of Alberti, further advanced the study of perspective by applying rigorous mathematical analysis to art. His book De Prospectiva Pingendi (On the Perspective of Painting) delved deeper into the geometric foundations of perspective, with works such as The Flagellation of Christ demonstrating his technique of architectural elements guiding the viewer’s eye into the depth of the painting.

Meanwhile, Leonardo Da Vinci expanded upon the concept of perspective construction in famous works such as The Last Supper, where the vanishing point is placed on Christ’s right eye, and the perspective is emphasized by his hands, which themselves are set almost parallel to the converging lines. Perspective, in other words, offered Renaissance artists a powerful new technique to achieve the same goal of hierarchy and symbolism that previous generations had strove for. Now, through perspective construction, artists could do so in a medium to satisfy even the untrained artistic eye.

The impact of the invention of perspective on the architectural profession cannot be overstated. As explained earlier, the eras before perspective saw buildings often conceived as collections of individual parts, such as plans, elevations, and sections, rather than as cohesive visual experiences.

With the advent of perspective, architects could now think holistically about how unbuilt proposals would appear in real space, taking into account not only the technical aspects of construction but also the spatial experience of the viewer. Clients, too, could be greater empowered in understanding how their desired scheme would appear, while architects could use perspective drawings to educate and capture the imagination of the general public, even those untrained in the reading of architectural drawings.

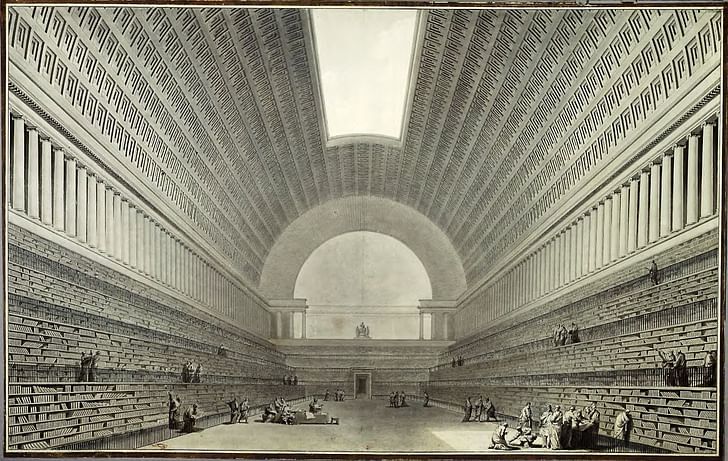

It would not be long before architects began to exploit these newfound abilities. Decades after Alberti’s treatise, acclaimed Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio would use perspective drawing to ground works such as the Villa La Rotonda in symmetry and proportion depending on the user’s vantage point. Three hundred years later, 18th-century Enlightenment architect Étienne-Louis Boullée would use perspective drawing to capture the public imagination in unbuilt works such as his famous interior perspective of the Bibliothèque du Roi in 1785.

The perspective renderings of Boullée, like those of da Vinci and Michelangelo in the centuries before, aptly demonstrate architecture’s ability to straddle the arts and sciences. Such renderings were more than technical documentation of a building, but they were also more than symbolic, abstract depictions of space ungoverned by the laws of reality. Rather, the invention of perspective offered a confluence of artistic beauty and technical precision.

A two-dimensional window into a three-dimensional experience, perspective ultimately created a portal into the world of the unbuilt.

The field of architectural visualization has changed significantly since the eras of Brunelleschi, da Vinci, and Boullée. Nonetheless, the underlying principles of perspective continue to dominate how we conceive of unrealized space. When the 19th century gave rise to photography, the human understanding of perspective gave rise to innovations such as focal length manipulation and the blending of photographs with perspective rendering.

From the early 2000s, meanwhile, an understanding of perspective would allow architects and visualizers to control the characteristics of images in digital modeling software. Even today, where immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality move architectural visualization from static pages to responsive headsets, the underlying principles of perspective observed six hundred years ago govern how our spatial experience is constructed.

A two-dimensional window into a three-dimensional experience, perspective ultimately created a portal into the world of the unbuilt. We will never finish exploring it.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

3 Comments

Well Mr. Walsh...you've picked a bugger of a topic for a short essay. It's wonderful to see this topic re-presented to today's architecture culture as digital tools have quashed the teaching of constructing perspective drawing, let alone its role in the development of architecture, in most contemporaneous schools of architecture.

Sadly, the imaging of a "render" or a "section" is just a click or two away in most softwares and most of the operates are unaware of such terms as "station point" or "vanishing plane".

That said, I fear your reporting is a bit overzealous. Brunelleschi was not so mathematical in his constructions of perspective as he depended on his perspective machine. And while Albert did indeed codify Brunelleschi's method in de Pictura (1430-35), in his ten books on architecture, De re aedificatoria (1450-52), he was hostile to the notion of architects using perspective at all! In his opinion, if architects wanted to explore the three-dimensional aspects of their work, they ought to do so vis-a-vis wooden models (which measured true), and NOT perspectival drawings (which lied). The truth of the thing depicted was paramount to Alberti for several reasons I'll not elaborate here.

Thank you for your essay and attaching the ink wash drawings of Etienne-Louis Boullée, which have a fraught relation to his equally fraught text. The drawing of the interior of the Bibliothèque du Roi, by the way, is currently owned and locate by/at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York.

It was even flatter in the Eastern miniatures where the drawings could simultaneously show more than one plane, i.e., frontal view and plan. This was a very significant contribution to world art. Maybe it is time to look at these more carefully and try to populate databases of art other than Western.

"Example of a map-like Ottoman miniature painting depicting Istanbul’s urban texture"

This is a great topic and wonderfully written. I'd only posit that people have always seen the world we see it, with or without perspective, as is clear in some exceptional cases prior to the Renaissance. The lack of records can also be attributed to the change in the status of the artist/architect around the late middle ages and the introduction of easily available rag paper which allowed for more 'experimentation' than a wax tablet or a sand box. This statement is especially romantic in it's portrayal of technology.

"As explained earlier, the eras before perspective saw buildings often conceived as collections of individual parts, such as plans, elevations, and sections, rather than as cohesive visual experiences"

A cursory reading of aesthetic or architectural treatises since antiquity would tell you this isn't the case. To your other point, the invention of mechanical perspective was a gift from the gods, especially when done by hand.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.