Our Archinect In-Depth: Licensure series concludes with a look back on a four-month journey through the U.S. architectural licensure system. Reflecting on the challenges and opportunities in the current system highlighted by readers and commentators, we offer final thoughts on how licensure helps and hurts the architectural profession.

As Archinect In-Depth: Licensure comes to an end, we can ponder the future of licensure by looking back to the beginning; both the beginning of this series and of licensure of itself. One of the earliest features in this series was titled ‘How ‘Architect’ Became Protected Title in the United States,’ charting the origins and evolution of architectural licensure in the U.S. as we know it today. As we explored, the move to license architects came partly as a result of the epidemic of building fires taking place in U.S. cities, with journalist F.W. Fitzpatrick noting that 1905 saw 8,700 fires in New York City and 4,100 in Chicago.

A century later, the potential for catastrophe remains in buildings not designed and delivered with due diligence. A stark reminder of this fact came earlier this month, when a public inquiry into the 2017 fire at Grenfell Tower in London came to an end, tasked with investigating how the fire spread through the recently-refurbished building, killing 72 people. Among the report’s findings was that the architect behind the refurbishment “bears a very significant degree of responsibility for the disaster.”

Meanwhile, this year has also seen a preliminary report published into the ongoing NIST investigation into the 2021 collapse of the Champlain Towers South condominium building in Florida, which killed 98 people. As we reported at the time, the report outlines several critical lapses in standard design practices and failures to meet building codes that were present from the time of its construction.

Grenfell and Champlain Towers South both serve as tragic reminders of the consequences when the AEC industry fails in its duty to design and deliver buildings that protect public health and safety. They also demonstrate that architectural licensing alone is not an adequate safeguard. Rather, a 21st-century model for public safety in the built environment should recognize that such safety is contingent not just on the competency of architects but on the competent and honest testing of materials, the competent management of buildings in use, competent regulation by officials, and competent responses from emergency services in the event of danger. At Grenfell, none of these competencies were met.

Faced with the reality that health and safety are not solely in the hands of architects, it may be tempting for some to advocate that the U.S. architectural profession follows those of the Nordic countries, where no protections exist on the use of the title ‘architect.’ In addition to potentially removing an obstacle on the long journey to entering the profession, the observation from one Architects Sweden official that “the securer the title, the lower the fee” is alluring for a U.S. profession often lamenting the low fees it receives for its services.

Relaxing licensure protections under the pretense that our current model is outdated or out of step with other nations runs the risk of “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

As our feature on this topic astutely observed, however, the U.S. is not Sweden. Series contributor Peggy Deamer found during her research that the licensing system of each country has evolved over time in response to that country's own unique cultural and political context. A move to deregulate the U.S. profession cannot, therefore, occur without extreme due diligence for the impact of such a move on public health and safety; impacts that may carry more weight in the U.S. than in Sweden, Norway, or elsewhere. To borrow a phrase from Justice Ginsburg, relaxing licensure protections under the pretense that our current model is outdated or out of step with other nations runs the risk of “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

This is not to say we should take our licensure umbrella for granted. If regulatory and social landscapes shift radically over time, and title protection is seen to hurt the profession and the built environment more than it helps, the Nordic countries show that a profession could survive and thrive in such an environment.

Our series has also shown that such a shift may be out of the profession’s hands. Just as the 1960s and 1970s saw Democrat and Republican governors in California either suggest or attempt to abolish architectural licensure, the near future may yet give rise to an idealistic state governor or legislator, on the left or right, who succeeds where Governor Brown failed. As writer and curator Ole Bouman commented on the aforementioned feature: “What energy could architecture summon at the next Jerry Brown on the horizon?” In other words, how would the profession fare in a rainstorm if our umbrella was snatched from our hands?

For now, however, it seems that the licensure umbrella is ours to keep. Attention must, therefore, turn to how nimble, strong, affordable, and accessible our umbrella can become. As our series has shown, there is ample room for improvement.

We heard from readers and experts alike about fundamental flaws on the path to licensure. Put simply, the current path takes too long, costs too much, and disproportionately challenges women and people of color. We heard how architecture schools are not adequately supporting candidates, while long office hours leave little room to study for the ARE; an exam that some feel is not fit for purpose. Indeed, some experts in our series felt that the path as a whole is too restricted, singular-minded, and outdated when measured against the reality of 21st-century practice.

The U.S. path to licensure may not be undergoing the headline-grabbing ‘fundamental overhaul’ underway in the UK system, but our series did hear how changes are afoot. A series of reforms, from the Integrated Path to Architectural Licensure (IPAL), NCARB Pathways to Practice, and abolishing of Rolling Clock Policy, are all directed at moving the path to licensure away from a singular ‘pipeline’ and towards what NOMA President Pascale Sablan described as a ‘multi-lane highway’ allowing candidates to change lanes and speeds on the journey through licensure. For the candidates who told us that the current path to licensure is taking a toll on their mental, physical, and financial health, these changes cannot come soon enough.

Those with power and responsibility over licensure must ask how reforms made today can strengthen the profession’s relevance throughout the 21st century.

When tailoring and strengthening our licensure umbrella, we must also reflect on how the rainstorm is changing. As our feature on the history of licensure explored, the modern licensure model grew out of the urgent new challenges and dynamics facing American cities of the late 1800s: rapid urbanization, social mobility, massive technological leaps, new materials, and the commercialization of the built environment. One hundred years later, these challenges are joined by novel forces no less consequential, from artificial intelligence to climate change, architectural labor unions to social polarization. Readers of this series will have seen how decisions made in the 1920s continue to exercise control over architectural training and licensing in 2024. Those with power and responsibility over licensure must similarly ask how reforms made today can strengthen the profession’s relevance throughout the 21st century.

We will conclude this series with a final, admittedly speculative, provocation. Some see an umbrella as a shield in a rainstorm. Others see it as shelter from extreme heat. Some see it as a branding opportunity, while one famously saw it as a symbol of protest. Indeed, some architectural designers see umbrellas as a design element, figuratively and literally.

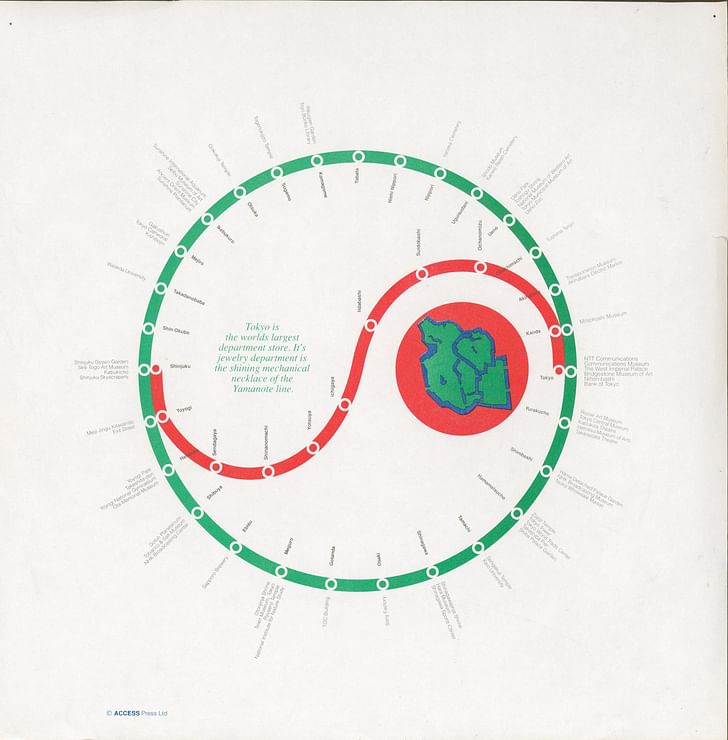

Likewise, our series included a reflection on how those in the software, information, and political arena saw relevance and applicability in the title ‘architect’ that went beyond building design. Throughout the 20th century, some individuals from an architectural background recognized the power of the ‘architect’ not just as a license holder but as a way of being, and surfed this wave of progress. Archinect readers have already met one such individual in Richard Saul Wurman, creator of both TED and the field of information architecture.

In the architectural profession of the mid to late 20th century, figures such as Wurman were the exception, not the rule. The profession at large, then and now, sees the appropriation of the title of architect by other fields as a threat and an act of disempowerment.

I cannot help but wonder how different our profession, and the built environment, would look today had we taken the opposite approach. Recognizing the appeal of the ‘architect’ in the worlds of both bits and atoms, could architectural institutions, media, commentators, and practitioners have done more to synthesize the design of physical systems such as buildings and cities with emerging digital and information systems? If they had, would holding an architectural license today mean more than verifying competence in designing and delivering physical environments? Would our profession still harbor its current despair over irrelevance, disempowerment, or financial exploitation?

Viewed through this lens, licensure today begins to look less like an umbrella and more like the walls of an ancient city; doing more to keep its licensed population inside the confines than it does to keep the invaders out.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

2 Comments

With every element of authority there is a slighter greater responsibility. As currently established, in this (Western) society, without licensure there is no "profession". Plumbers would be engineers or architects; but both are licensed. Plumbing is a trade that is a skill licensed to install, not design. The knowledge of, and responsibility for, the overall design criteria (systems integration and function) goes far beyond that of mechanical (physical/technical) skill. The plumber need not concern him/herself with the myriad of elements that surround the wholistic aspects of human/social environment. Yet, social psychology will not enable one to flush the toilet. It is essential we continually recognize the role architects play in that environment and the encompassing responsibilities involved. Architecture is not journalism, nor is it theory. One aspect of "design" is interpretation but only one. Here repeated is how an old engineer once scolded a young architect: "Kid, why don't you go into medicine? That way you can only kill one person at a time!

"Viewed through this lens, licensure today begins to look less like an umbrella and more like the walls of an ancient city; doing more to keep its licensed population inside the confines than it does to keep the invaders out."

This has always been my view. A lot needs to be addressed in the profession.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.