Welcome to Archinect In-Depth: Licensure. Over the coming weeks, Archinect will explore the journey undertaken by those in the United States seeking to practice as a licensed architect, including reflections on the history of licensure, comparisons to other countries, the cost and length of time taken to complete licensure, demographic inequalities within the process, and a series of possible futures.

At the beginning of my architectural education, I was told of two specific things I would never be able to ‘unsee,’ having learned about them in architecture school. The first was about bricks. I distinctly remember sitting in a now-demolished building at Queen’s University Belfast in one of our earliest classes on building technology, being shown the difference between Stretcher bonds, English bonds, Flemish bonds, and so on. Our lecturer warned us that, from then on, we would never be able to look at a brick wall without identifying which bond was used to build the wall. Twelve years later, that prediction stands true.

The other ‘unseeable’ was not a pattern, method, or object but a word: ‘architect.’ We were told that, in no uncertain terms, a cardinal sin of our profession would be to call ourselves an architect before jumping through the necessary hoops.

Passing my bachelor’s did not make me an architect. Passing my master’s did not make me an architect. Working in practice did not make me an architect. Joining professional bodies such as RIBA or AIA as a student member did not make me an architect. I was even warned that passing my licensure exams did not immediately make me an architect. I could only legally call myself an architect when the Architects Registration Board (the United Kingdom’s equivalent to NCARB) had affirmed that I had completed my journey through education, experience, and examination, and had placed my name on the UK’s Architects Register. To call myself an architect before then would be a criminal offense with serious ramifications for my future career.

We were told, in no uncertain terms, that a cardinal sin of our profession would be to call ourselves an architect before jumping through the necessary hoops.

Such was the coveting of the word ‘architect’ that several lecturers of mine would insist on spelling it with a capital A regardless of grammatical context, with a religious undertone that reminds me of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic line to Mike Wallace: “You spell ‘God’ with a capital ‘G,’ don’t you? I spell Nature with an ‘N’, capital.”

From then on, the word ‘architect’ would stand out like a sore thumb or, worse, a Flemish Bond. We would notice when university colleagues used titles such as ‘student architect’ or ‘assistant architect’ on LinkedIn profiles during their bachelor's or master's studies. We would notice when work colleagues used the title ‘architect’ on email signatures long before sitting licensure exams. After graduating from university, we kept a mental scoreboard over which colleagues had and had not gained their license, a factor that seemed to matter far more than how prestigious their office was, how beautiful their location was, or even how impactful their work was.

The topic of licensure, though not as recurring a theme in architectural discourse as climate change, labor, or artificial intelligence, often evokes strong reactions when mentioned.

We are not the only ones. The topic of licensure, though not as recurring a theme in architectural discourse as climate change, labor, or artificial intelligence, often evokes strong reactions when mentioned. When Princeton University School of Architecture Dean Mónica Ponce de León issued a statement in June 2020 calling for licensure to be “eliminated or radically transformed,” Archinect’s news article reporting Ponce de León's comments attracted almost 100 comments, many of which spanned hundreds of words. Weeks later, Archinect published an interview with Ponce de León on the subject, which also garnered almost 100 reader comments. The subject is no less emotive on the Archinect Forum, where discussions on using, misusing, and protecting the ‘architect’ title can attract over 100 comments, while one thread’s proposition that ‘NCARB is killing architecture’ has attracted almost 300 comments.

Sometimes, the topic can emerge in unexpected places. When Archinect recently published an article that used artificial intelligence models to predict the 2024 Pritzker Prize winner, one commentator replied: “Someone should also tell AI that you have to be a licensed architect to win the Pritzker Prize, not a designer…. so Neri Oxman and Thomas Heatherwick are both not eligible at this time,” sparking a debate between the commentator and Archinect moderators on the prize’s eligibility.

As a topic of discussion, licensure evidently evokes an emotive response from the architectural community and, as such, demands a deeper, wider, and more rigorous investigation than what is currently on offer in U.S. architectural discourse.

The emotive power of licensure and title protection on Archinect does not exist in a vacuum. In both the United States and the United Kingdom, institutions overseeing the architectural profession are vocal through the press in their protection of the ‘architect’ title. In the United Kingdom, ARB maintains a public register of prosecutions it has taken against those it believes to be misusing the title, which is routinely carried through the press. In 2012, the body sparked a backlash after asking the UK’s Building Design magazine to stop referring to Renzo Piano and Daniel Libeskind as architects, leading ARB to issue an apology. In the United States, meanwhile, the AIA’s Architect Magazine ran a story in 2009 titled ‘Trust Me, I’m an (Unlicensed) Architect’ detailing action taken against those who misuse the title, while AIA Massachusetts executive director John Nunnari recently gave an interview to the Boston Society for Architecture outlining the steps the state takes to protect the title.

As a topic of discussion, licensure evidently evokes an emotive response from the architectural community and, as such, demands a deeper, wider, and more rigorous investigation than what is currently on offer in U.S. architectural discourse. With that in mind, welcome to Archinect In-Depth: Licensure.

Following the conclusion of Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence, the coming weeks and months will see Archinect publish a series of features and analyses approaching the subject of licensure from a variety of angles and lenses. To those who sit in hot anticipation of Archinect In-Depth: Brick Bonds, the wait sadly continues.

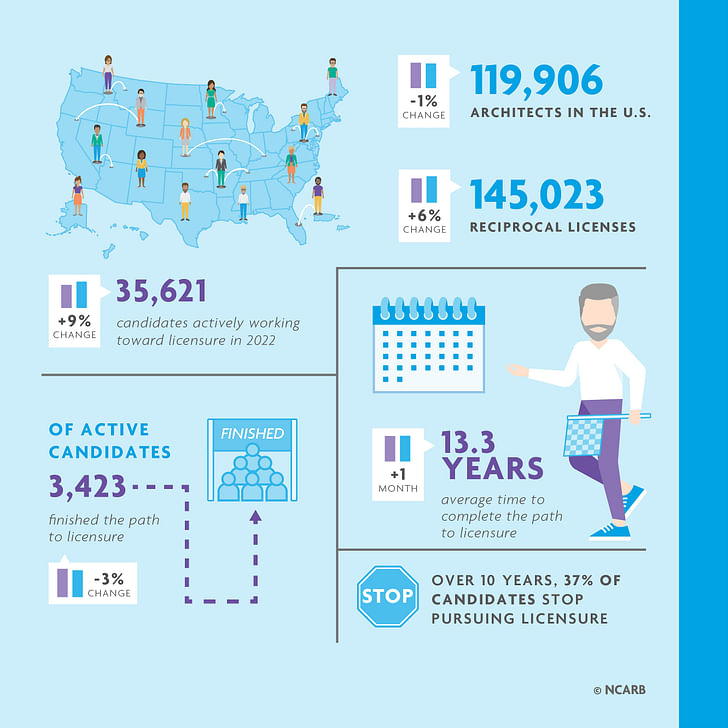

Let’s begin this journey with an overview of architectural licensure. As of 2023, there are almost 120,000 licensed architects in the United States, according to data from the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB), the body that oversees U.S. architectural licensure nationally. In addition, there are approximately 35,000 candidates actively working towards licensure. Unlike countries such as the United Kingdom, where an architect license covers the entire country, candidates in the U.S. must earn a license from the regulatory board of one of 55 ‘jurisdictions,’ meaning an architect licensed in California is not automatically entitled to practice as an architect in New York. In practice, however, there are 145,000 reciprocal licenses held by U.S. architects, signaling that the average architect is licensed in more than one jurisdiction.

In 85% of cases, the route to licensure begins with an architecture degree from a program accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB). In addition to this ‘education’ component, candidates must fulfill an ‘experience’ component through NCARB’s Architectural Experience Program (AXP). The AXP sets out 96 key tasks across six practice areas, with candidates required to demonstrate their ability to perform those tasks through 3,740 documented hours in practice and/or practice-adjacent settings.

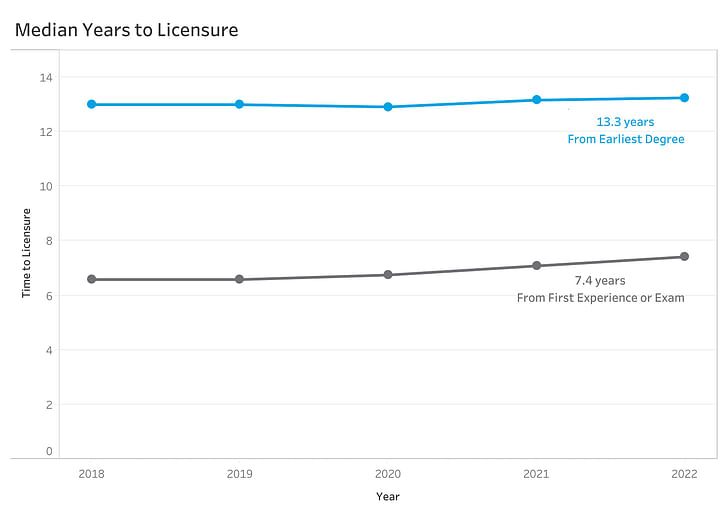

On average, the licensure process takes 13.3 years for an individual to complete from the time they start their first degree.

The final component of licensure, ‘examination,’ is fulfilled by passing the Architect Registration Exam (ARE), an NCARB-administered examination with six sections designed to assess a candidate’s knowledge and skills regarding architectural practice. Candidates must pass all six sections, or ‘divisions,’ of the ARE to complete licensure. With education, experience, and examination components fulfilled on their NCARB Record, as well as any additional elements required by their chosen jurisdiction, candidates may formally apply to join their jurisdiction’s register of architects.

On average, the licensure process takes 13.3 years for an individual to complete from the time they start their first degree. In 2022, the most recent year for which data is available, 3,400 candidates completed the path to licensure, while 37% of individuals who began their NCARB Record ten years ago have stopped pursuing licensure.

However, a descriptive timeline of the path to licensure does not tell the full story. To understand the path to licensure, why it exists, where it works, where it fails, who it fails, and what its future is, we are called to spend the following weeks playing with several questions.

Where did the path to licensure come from? How does U.S. architectural licensure compare to other countries? What demographic inequalities exist along the path? Why does it take so long and cost so much? How adequately does it prepare candidates for practice? How might the path evolve and diversify in response to forces in and beyond the architecture world? Do other models exist? Do we even need architectural licensure at all? Welcome to Archinect In-Depth: Licensure.

Do you have strong views on architectural licensure in the United States? Let us know in the comments, or write to this series’ lead at niall@archinect.com.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

32 Comments

Here in the USA, the primary function of NCARB seems to be propping up the old boys networks (forgive my use of a gendered term, but the big firms are almost exclusively run by men). This network has sunk its teeth into the profession and constitutes a diffuse monopoly that, with the help of the state, is allowed to extract maximum profit while eliminating competition from recent graduates who aren't willing to run the gauntlet by putting in years of grunt work at these corporate sweatshops.

Outside of the USA licensing is often much less restrictive, and as a result, many other countries consequently have a built environment of a significantly higher quality by any measure. Greater participation by designers in our culture would be a net positive and the heavy burden imposed by the USA's onerous system of licensure creates a de facto class of professional elites. Often these elites came from existing wealth networks and they could afford to spend years working for next to nothing because they graduated without debt (no student loans, thanks dad) and have never worried about living paycheck to paycheck.

With structural engineers doing most of the heavy lifting in the profession anyway, it seems absurd that licensure in the USA takes an average of 7-13 years of commitment (per the article data). The vast majority of design decisions made by architects are not a matter of life and death, so why should the timeline for cultural participation of architecture graduates be comparable to medical school?

The issue of quality in the built environment in the united states has nothing to do with the quality of the designers or licensure of professionals and everything with what the market demands and clients want.

hyperdimensional - may I ask how long you've worked in the profession and if you're an architect?

I would say that the built environment is more a function of the amount of lawyers in the US than licensure or quality of designers. What I will say though is that the current insane licensing process in the US does tend to leave out quite a few talented designers who are not able to finish the licensure process before life obligations take over.

I think the licensing process should be the same no matter where you went to school. If you can pass the ARE you're an architect in every state.

hyperdimensional - why the thumbs down? I just wanted to know how you came to your insight on this and how long it took you to come to your conclusions.

licensure it primarily a form of gatekeeping - like others said above, laws, code and zoning are what ensure safety, not credentials.

I don't agree with you square.

In my opinion, you have to know about the laws, codes, and zoning. Then you have to know how to implement them into a building so that they work. The second part is how you try to keep buildings safe. That's why licensing is required.

You got a downvote because you tried to make this about ME instead of the topic.

It's not even possible to get a building permit if the design doesn't meet code or doesn't fit into the zoning regs. Those are matters of bureaucracy and plan review, which are handled before any construction can begin.

"Unlicensed architects" are not a threat to public safety, they are a threat to the established power structures and capital flows that keep the elites of this profession fat and happy.

I'm asking you about your experience to try and understand how and why you came to your conclusions. You're making this about yourself.

A building department or code reviewer won't catch everything and isn't the one responsible for ensuring that the building is safe. That responsibility is the architect.

In addition, when a review finds something nonconforming they don't have to tell you how to make it comply. They just have to say that it's not complying.

Just because an AHJ allows something doesn't mean it's an ideal solution or should be done.

How the building performs (thermal, weather protection, environmental impact, energy usage, ect) are the responsibility of the architect.

The power structures you're upset about are a valid concern. Especially when it comes to race and gender. Other than that if you want to start your own firm and design nothing is stopping you other than your creativity. You don't even need to be an architect to do that. As such your idea that unlicensed architects are a threat to the elites is a bit far fetched. The average architect in the US makes around $100,000 a year so your fat and happy part of your comment is simply ridiculous.

chad - why can't experience at an office qualify you for those things? i'm a marginally better architect because of the exams, over 95% of what i know about all of these things comes from practice, not studying. we all know of countless unlicensed "designers" who are perfectly capable to delivering well-detailed safe buildings. i stick by what i said - exams are primarily an economic tool to exclude a certain number of people and to make others a lot of money.

Square - they can come from pro practice internships. I never said they couldn't. I simply disagree that licensure is a form a gatekeeping. Personally, I think all states should allow the 10 year alternate path to become an architect.

On a side note: In this portion of the thread you only stated licensure was a form of gatekeeping. You never brought up exams being an economic tool to exclude people and make money.

Question: if testing is a tool of oppression how do you recommend we show a person has the minimal skills to design buildings?

ditto for exams, though i think "tool of oppression" is a bit heavy handed. i've stated the means through which i believe safety and competency is determined. to flip the question, how do paper exams demonstrate the skills necessary to design buildings when it's entirely possible to pass them with 0 professional experience? skill is demonstrated through experience, which is how this all was done long before exams, ncarb etc.

square -

First - laws, code and zoning don't create buildings that don't harm or kill people. Understanding those things are what accomplishes that.

Second - the AHJ that review designs for laws, code and zoning don't check everything that keeps a building safe. They also don't catch everything that is in their scope. Even when the AHJ dose catch errors they do not tell anyone how to fix them.

Third - The architectural exam is intended to show that you have the minimum knowledge of laws, code, zoning, engineering, and building sciences to create a building that will not harm it's occupants.

Fourth - how was it shown that you had the minimal knowledge before licensing? - Simple, you didn't. Anyone who could get a client with enough money could design any building. People died because of it.

Finally - it may be possible to pass the ARE with no experience. Do you happen to know anyone who's passed the ARE with no experience in architecture? I ask because in my experience most architects don't understand the laws, codes, and zoning associated with architecture. Just look at this forum, even the discussion of this article for examples.

What I don't understand is why can't the educational system integrate all the licensure requirements into their programs like in many other countries. make it 6 years, 2 full semesters of professional practice, building sciences, structures, mep, etc. it's not that hard and people would come out of school knowing something.

Yup, working currently with a few students from an elite private college in downtown LA (cough cough), who cannot even lay out a basic single family home.

Exactly. My least favorite colleague at a well known design firm had an M.Arch from an elite private college in downtown LA and didn't know what steel studs were. Architects are becoming irrelevant because Architecture schools don't teach either the business of Architecture, and teach the Art of Architecture as if it never had to be executed in a world inhabited by humans and governed by gravity.

I think you can take the ARE after 10 years of working under an architect right? that's 3.3 years less than going to school and spending good money.

Janosh, I think pretty soon AI will wipe out jobs of those people

JLC-1 - you can only do that in 12 states. Soon that will be down to 10 states. Also, there is no reciprocity so you have to redo the 10 years of internship for each new state you want a license in.

If you have an accredited degree you only need 2.5 years of internship.

https://www.ncarb.org/get-licensed/licensing-requirements-tool

Let's contrast this to PE licensure....A candidate for a PE license has to have an undergraduate degree, work under a licensed PE, and takes a 2 day test - in the engineering discipline they have the most knowledge thereof. Once they pass, they can stamp anything they believe they have knowledge enough to stamp. So they can stamp architectural drawings - if they feel qualified. Why are we held to such a higher standard than them? Both disciplines are equally important for a safe and functional building.

I learned far more from 'on the job training' and CEUs than I did studying for the ARE. And I remember and use my 'on the job training'. I don't remember anything that I crammed for the test....

That is a great analogy. Most licensed architects I know don't stamp their own drawings because they don't want the legal exposure. The engineer does the engineering, the architect handles matters of a more subjective and experiential nature. Yet the architect is subjected to a much longer path to licensure, comparable to that of a brain surgeon. It's an anachronistic state-supported anti-competitive measure that does not reflect the reality of the profession today.

I agree that the ARE when I took it (4.0) had areas that had nothing to do with the actual practice of architecture. More so, the study guides were actually worthless as you needed real world experience to pass the exams. It seemed like the exam was more to test your basic knowledge of the legal and technical aspects of being an architect. Architecture is a constantly evolving and changing profession. Any licensing exam will only be able to touch on the very basics that an architect will need to practice and not kill people.

The young professionals that are taking the ARE 5.0 say it's much more in line with how we actually practice architecture (at least at our firm).

Personally I found the exam to be much easier than actually practicing architecture.

From my experience of getting the licensure, the biggest flaw I noticed was that the process heavily favours who can take tests well. I took all the tests, never failed. I did study at least 3 hours a day for 8 months, but I know people who have done similar amount of studying and still have hard time passing since they are just not good at taking tests.

After I passed and got my 3 years of experience, I applied to the state, and became an 'architect' in 2 months. No way, I can actually do the job description of an architect unless it is for a small single-family suburban home, and that is only because I was lucky enough to work at an under-staffed design-build firm that had my feet on fire for 1.5 years doing those kinds of projects.

My verdict is that in some ways, the licensure should be seen like the building code - the bare minimum, if one has the license. But on the otherhand, someone without a license can be a much better 'architect' in every other way, also..

Only real thing I can say for certain is that schools should be teaching actual architecture materials at school, incorporate into the syllabus. Afterall, aren't the accredited programs 5 years because there are (supposedly) so much to teach? Looking back, I cannot believe how I was hired out of college. The only explanation I can come up with is that it is an open secret that the schools' program are lacking, and even though I was very incompetent, I was no more incompetent than my peers.

Passing the exams (licensure) is the bare minimum of knowledge one needs to be an architect.

An engineer once said to me: "Kid, why don't you go into medicine? That way you can kill only one person at a time! There is one overriding reason for licensing an individual to practice architecture: The protection of life, health and safety of the general public. HSW: ever hear of it? Architects and engineers do not protect "welfare". No one, particularly Americans, cares about "(A) architecture". That is a subject of concern to a very small population of those who practice it. To the rest it is a business melded with an aspect of social elan. Or, more commonly (for those who are sufficiently rich) an aspect of social lubricant wrapped in a veneer of postured respectability.

That there is a near total disconnect between school and licensure is one of the craziest things in this regime. Granted, design schools aren't exactly trade schools. But far too many schools have gone the other way - not least thanks to faculty and leadership who have neither experience nor interest in professional practice - and done their darn hardest to exclude any semblance of the profession from studio. They're a few steps away from turning into full fledged art schools like that AA studio that specializes in training illustration and movie-making.

Your comment about faculty lacking actual experience rings true, based on the school where I first enrolled for my M.Arch. I was being taught by young academics who were good at theory and 3D modeling software but had largely failed to make a dent in the physical world and had retreated into academia. Fortunately I was able to transfer to a school where the faculty was more experienced and pragmatic, and the distinction between the quality of education at the two schools was massive, despite both being ranked in the top 5 at the time.

making licensure about education at uni is risky. There is a disconnect between education and practice, granted. BUT, that is not because uni is not teaching enough, it is because 6 years is not enough time to get good at something for an average person. For exceptional people who are fully involved and paying attention it may even be 2 years more than they need to be amazing at all of the stuff that architects do. But we create an architecture curriculum for everyone, not the 1 or 2 exceptional students that go through the system every year in any given school. If you are an educator you know exactly what I mean. Its the same at elite schools as much as at colleges.

University education is intended to give you the basics and to teach you to learn how to learn, so you will be able to evolve and grow after graduation. It isn't a place to turn out exacting cogs for a machine. That would actually be a stupid use of resources. Anyone who has been out of school for more than 10 years knows that the world changed enormously since they graduated and that education needed to change to keep up. Mass timber was not a thing when I went to school. Digital fabrication was, but it wasn't very good (as it is now), and no one ever mentioned BIM. But we are all suing that stuff everyday as architects now and not batting an eye. Licensure recognizes that reality, and leaves room for architects to pick up the the skills they need after finishing school. Only thing I would add to arch education is more about business and PM roles, but time and life are short. We all have to make trade-offs...

It would be great if we could practice architecture right out of school as fully licensed creators of awesomeness. We all know that is not how it works for most of us. So we have a more complicated system in place to compensate for the average way we all actually learn and grow. Then we add on layers of protectionism and some of the gatekeeping stuff that was mentioned above, because average humans absolutely LOVE to rig any game they are part of. And we get what we get, a complicated mess that works but isnt great. Like pretty much everything else that humans do. It does need to be reformed, but only because every system needs to be reformed and critically evaluated, not because architects are shit at organizing our own profession.

"University education is intended to give you the basics and to teach you to learn how to learn"

"University education is intended to give you the basics and to teach you to learn how to learn". The problem is this too general of a principle. How can anyone disagree with this with sound mind? Too many professors and schools in my personal experience used similar general and vague principles/phrases such as "renaissance man education" to teach us how to use Photoshop and Grasshopper for 5 years. Looking back at my school's syllabus, putting so much emphasis into creating building designs that are glorified sculptures, and putting so little emphasis on theory and history, I do not think they taught us how to learn.

Echoing will's comment above that turning the architecture schools into trade schools isn't a good idea. I compare it to students who only do computer science and graduate without any humanities and history thus have no perspective on how their proposals for "new" tech are either 1. remaking of old tech (e.g. Uber Pool is just a bus) or 2. dangerous ("FSD" in Teslas). As will said, in large part college is about learning how to learn.

My comment above has nothing to do with licensure. My opinion on it is below:

It's inarguable that licensure is used as gatekeeping. As with everything in the history of the US there are racist and classist reasons for how licensing became entrenched. As The Coup sang "You are not a riot, you are a pretty piece of paper which is signed by murderers" - I think of my own license every time I hear that lyric. Licensure has absolutely zero to do with talent, either. Some shitty designers are licensed and some brilliant designers are not. There are countless avenues to pursue a fulfilling life in the world of building design with or without a license.

That said, if you *can* get a license why not do it? It feels *really good* as the finish line of school, internship, and exams to say "I'm a registered architect."

To anyone waffling about it, just do it.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.