According to recent data, the demographics of candidates on the path to architectural licensure are beginning to counter the longstanding underrepresentation of women and people of color in the profession. However, deeper studies of the licensure experience reveal ongoing disparities along gender and race on exam pass rates, completion time, financial burdens, and external support.

In this latest edition of Archinect In-Depth: Licensure, we explore how architectural licensure could evolve to address these inequalities, including perspectives with NCARB CEO Mike Armstrong, NOMA President Pascale Sablan, and architect, author, and Archinect contributor Melvin L. Mitchell.

In 1892, North Carolina-born Robert R. Taylor became the first accredited African-American architect in the United States, in addition to becoming MIT’s first Black graduate. Thirty years later, in 1923, Paul Revere Williams would become the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects 66 years after the institute’s founding. In 1942, meanwhile, Beverly Loraine Greene would become the first licensed African American woman architect in the U.S., earning her license in Illinois almost five decades after that state became the first in the U.S. to require licensing for architects.

As the U.S. architecture profession developed over the past century, it has remained demographically unrepresentative of the country it designs for. In 2024, 82% of U.S. architects are white, despite forming 60% of the U.S. population. White men are particularly overrepresented in the profession, constituting 62% of U.S. architects though only 30% of the population. Conversely, 2% of U.S. architects are Black or African American despite forming over 14% of the population, while 6% of U.S. architects are Hispanic or Latino despite comprising over 19% of the population.

For those currently entering the profession via the path to licensure, demographic data is more promising. As Archinect recently reported, new NCARB data shows that licensure candidates are steadily becoming more demographically diverse, with 47% of licensure candidates and 33% of new architects now people of color, while 46% of candidates and 40% of new architects are women. Last year, 43% of candidates completing the AXP identified as a person of color, as did 35% of ARE examinees, the latter being 10% higher than in 2019.

As the U.S. architecture profession developed over the past century, it has remained demographically unrepresentative of the country it designs for.

“The numbers we're seeing also indicate that we're seeing more diversity in enrolment in schools, which is terrific,” NCARB CEO Mike Armstrong told me in a June 2024 conversation, weeks before the latest figures were published. “We're getting close to gender parity in terms of licensure candidates, and representation by non-white candidates is over a third at this point. We're getting closer and closer to representing U.S. society as a whole, but we still have more to do.”

While recent years have seen growing demographic diversity among licensure candidates, data also shows that within the licensure process itself, inequalities remain. In 2023, the average white candidate who completed the path to licensure took 12.9 years to do so, while Asian and Black candidates took four months longer, and Hispanic or Latino candidates took six months longer.

Analyzing the data by gender offers greater signs of progress, however. In 2023, women made up 51% of new NCARB Record holders and 52% of candidates reporting experience. On average, women are completing the path to licensure one year faster than men, as they have done for the past five years.

Typically, women and people of color are also more likely to complete the AXP in a shorter time frame compared to their peers. Explaining the divergence, NCARB notes that “men and white candidates tend to begin reporting experience younger (often while in school), but then have a period of slow progress because they aren’t working full-time.”

We're getting closer and closer to representing U.S. society as a whole, but we still have more to do. — Mike Armstrong, CEO, NCARB

In contrast, data on the ARE highlights a landscape disproportionately favoring white and male candidates. The latest NCARB data found that men are more likely to finish the ARE in under two years, while white candidates are 7% more likely to complete the exam in under two years than Asian students, 14% more likely than Black candidates, and 18% more likely than Latino candidates. White men also have the highest pass rate on all six ARE exam divisions. By contrast, Black or African American men had the lowest.

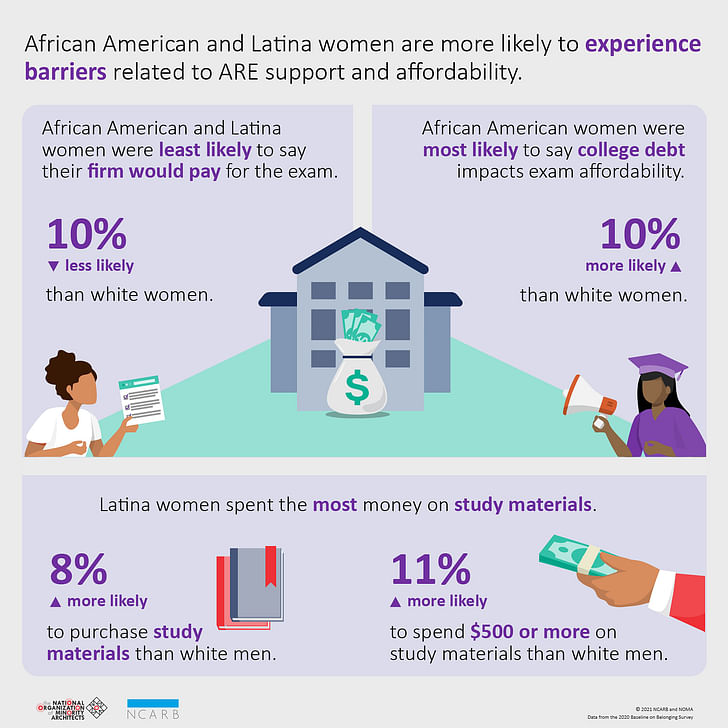

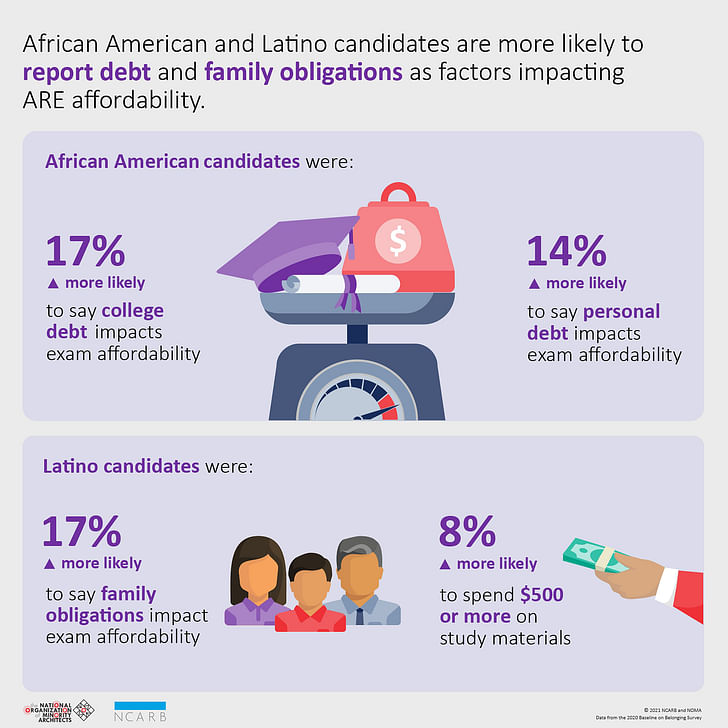

In their joint 2020 Baseline on Belonging report, launched to identify how minority professionals experience obstacles on the path to licensure, NCARB and the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) identified several potential sources of the inequalities in exam data.

According to the report, African American and Latino candidates are 5-6% less likely to receive firm support toward the cost of the exam, while African American women are 10% less likely to say their firm would pay for the exam. African American candidates are also 17% more likely to say college debt impacts exam affordability and 14% more likely to say personal debt impacts exam affordability. Meanwhile, African American women are 10% more likely than white women to say college debt impacts exam affordability.

Summarizing the challenges faced by minority demographics on the path to licensure, NCARB’s Armstrong distills the Baseline on Belonging findings into two words: cost and culture.

“Cost is a word that stretches pre-college to post-college,” Armstrong told me. “It covers student debt, and it covers average salaries after one graduates. It covers your economic status before and after you graduate, and the socioeconomic conditions that you are thrust into based on systemic racism and other biases in our society.”

To combat the cost challenge, Armstrong points to NCARB’s moves to reduce the cost of test prep, which, for some candidates, can approach $10,000 per year. “Our practice exams are full length and have the same mix of questions as our real exams,” Armstrong notes. “Our data indicates that people who take our practice exam have a 16% higher probability of passing our regular exam. And if you are a person of color, it's as much as an 18% higher probability. So we're addressing cost in that way. Culture is something that is a shared responsibility, not only between us and other organizations but by our society as a whole.”

The point is to make sure that our profession is so diverse that communities who are often overlooked now have somebody representing them that can speak to them. — Pascale Sablan, President, NOMA

For NOMA President Pascale Sablan, building a culture of equality in the profession goes beyond statistical representation and must also encompass how the profession delivers for communities. “The point isn't to just get one thousand or five thousand new Black architects,” Sablan told me in a separate June conversation. “The point is to make sure that our profession is so diverse that communities who are often overlooked now have somebody representing them that can speak to them. We are right now reconciling how the built environment, urban planning, redlining, and gentrification have perpetuated harm to marginalized groups. Having that conversation and trying to convince greater society to engage with us, as well as potentially see us as a career path, is also part of that challenge.”

Reflecting on how the licensure process can be reformed to meet the challenge, Sablan points to the recent elimination of NCARB’s Rolling Clock Policy, which previously placed a five-year expiration date on passed divisions of the ARE. The decision to retire the policy was announced in 2023 following the Baseline on Belonging findings, with NCARB reporting earlier this year that the reform has particularly benefited minority demographics. Looking to the future, Sablan set out her vision for a pathway to licensure, which is less like a single, fixed pipeline and more like a multi-lane highway with a variety of options for licensure candidates of all needs and circumstances.

“A pipeline insinuates that there's a singular entry point and a singular outlet,” Sablan told me. “If you miss that point, you missed out entirely, you're not in it anymore. What we're trying to reframe is this idea of a highway of on and off-ramps with rest stops along the way. Maybe the lane you want to drive on is the lane that doesn't include licensure, and that's fine, but you're still engaging in the built environment.”

“For someone else, maybe licensure is the destination,” Sablan continued. “We want to give you the option of the fast lane with no obstacles in your way. If you need to take a rest stop to have children or to care for a loved one, you can take a rest, get what you need, and be able to get back into the lane to continue your journey through the profession. I am known for speaking a lot about women and people of color, but there's also an intergenerational challenge that's happening here as well.”

On how this multi-lane highway can be built, both NOMA’s Sablan and NCARB’s Armstrong point to NCARB’s Integrated Path to Architectural Licensure (IPAL) initiative, which allows students in the process of earning a degree from a NAAB-accredited program to complete the AXP and ARE concurrently. Launched in 2015, 33 NAAB-accredited programs at 28 U.S. schools are currently participating in the IPAL initiative.

What we're trying to reframe is this idea of a highway of on and off-ramps with rest stops along the way. — Pascale Sablan, President, NOMA

“IPAL graduates have a much higher probability of getting a license roughly two years after graduation on average,” Armstrong told me. “That’s a significant shortening of the path to licensure. We think the idea of IPAL is a good one, but we want to now do some other things with IPAL to incentivize using the practice exams and figure out a better way to get people placed into jobs while they are in school.”

“We're creating more opportunity for diverse individuals who are not affluent to study architecture and design without going into a six-figure debt as part of it,” Sablan told me separately. “If I'm able to work on my licensure while I'm in school and I'm able to do my community college degree, that also tightens up the timeline and makes the path more equitable.”

The potential for IPAL to play a role in the reform of architectural licensure to support aspiring Black architects was identified in a previous two-part op-ed published on Archinect in 2020 by Melvin L. Mitchell FAIA, NCARB, NOMA. A practicing architect for over four decades and author of the book The Crisis of the African American Architect: Conflicting Cultures of Architecture and (Black) Power, Mitchell spoke to me recently on how institutions could capitalize on the potential of IPAL, which he described as “a revolutionary act” that “freed up people from having to be low paid farm workers in an architecture system.”

Despite the potential he sees in IPAL, Mitchell is critical of the slow adoption of the initiative by architecture schools in Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), of which there are seven in the U.S. currently. While IPAL was launched in 2015, Morgan State University became the first HBCU to adopt IPAL in 2022, followed one year later by Hampton University.

“Unfortunately the HBCU architecture schools were the last ones to get on the IPAL train and in fact, they are still boarding it,” Mitchell told me, adding that apart from Morgan State and Hampton, “the others act like they never even heard of it or they don't know what to do with it or about it. And so that's unfortunate.”

Insofar as increasing the numbers, role, and relevance of Black architects, you can’t get there without going back and looking again at the HBCUs. — Melvin L. Mitchell, FAIA, NCARB, NOMA

“They were once really focused on producing Black architects that didn't just graduate and get degrees but graduated, pursued licensing with fairly high levels of success, and opened entrepreneurial firms,” Mitchell explained. “Despite the growth of Black schools in numbers and populations, that has fallen off the table. There are all sorts of reasons for that. Primarily what's happened is that these HBCU programs have followed what appeared to be trends and inclinations in the traditional white institutions that were okay for those institutions, but didn't bode well for the Black schools.”

“If you look at the HBCU programs, they don't produce architects, they produce graduates who go into all sorts of things, but rarely become either licensed architects, and even more rarely do they venture into starting firms,” Mitchell continued. “The HBCU schools are primarily feeding grounds for large corporate firms, white firms in terms of employment, as well as other avenues you can go into with an architecture degree, but rarely architecture itself in so far as a productive mode of building.”

For Mitchell, trends in HBCU architecture schools are more damning when compared to the relative success of HBCU medicine and law schools in increasing Black representation in their respective professions in recent decades; a subject which Mitchell also unpacked in his 2020 features for Archinect.

“One of the reasons that law and medicine do as well as they do is because you've got to be a reasonably educated, mature person before you proceed down that track,” Mitchell told me. “Architecture is still taking 18-year-olds and dropping them into this crazy studio culture. Four or five years later, they're either worn out or they may get through but will never get back on track.”

“One move I am really keen on is that HBCU programs limit admission to people with degrees in something else, and preferably not architecture,” Mitchell added, cautious of what he sees as the disproportionately negative impact of a “mythical” studio culture on young Black students. “Insofar as increasing the numbers, role, and relevance of Black architects, you can’t get there without going back and looking again at the HBCUs.”

Mitchell may be critical of the current pathway to licensure that many Black students experience in their architectural education. However, when asked if the concept of licensure is itself a gatekeeper to demographic minorities, Mitchell is not in favor of abolishing the requirement.

“I just don't think that that's workable,” Mitchell told me. “It is definitely not workable for Black architects right now anymore than it would be to advocate that we stopped licensing lawyers and medical professionals. Things may well come to that, but right now, given the struggle Black people are in, how we fit into this whole big picture, where we've been, and where we're going, that doesn't fly for me.”

That's where NOMA as an organization has focused on: Addressing the elements that can make taking the exam truly be about competency. — Pascale Sablan, President, NOMA

When asked a similar question, NOMA President Pascale Sablan likewise differentiates between the need for licensure and the pathway through which that license is acquired.

“I didn't perceive licensure as the barrier,” Sablan told me. “I perceived the cost of education, the cost of the examination and study materials, the content in the examinations, the unrealistic challenges of getting it all done by X amount of time with the lack of resources that are offered by firms in people who are testing, as the barrier.”

“These are the parts of the infrastructure of attaining the licensure that felt unjust and inequitable,” Sablan added. “That’s where I have focused on. That's where NOMA as an organization has focused on: Addressing the elements that can make taking the exam truly be about competency.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.