Throughout the 20th century, every state and territory across the U.S. passed laws establishing a requirement to license architects. Since then, no jurisdiction has successfully repealed such a requirement. In the late 1970s, however, California almost became a notable exception.

The story of how California nearly abolished architectural licensure, a multi-decade saga led by some of the most prominent leaders across the political aisle, holds lessons and reflections for the profession of today, including its members and representative bodies. In this latest edition of Archinect In-Depth: Licensure, we retell the story with insights from those involved at the time.

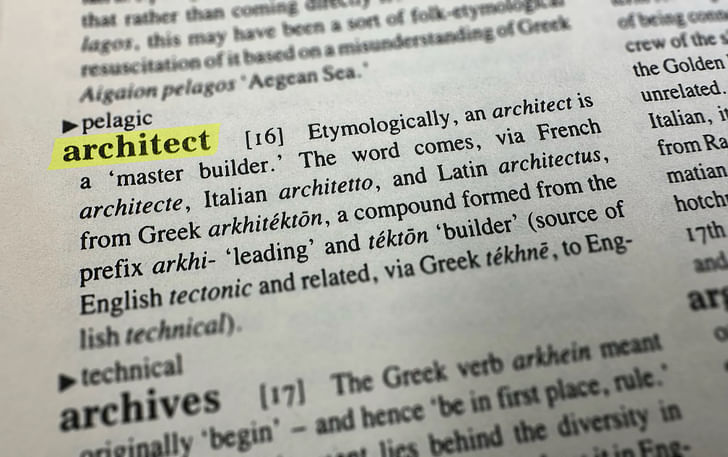

During the 20th century, trends related to protecting the title ‘architect’ flowed in only one direction. In 1897, Illinois became the first U.S. state/territory to demand architects be licensed, with the Northern Mariana Islands completing the map almost 100 years later in 1984. In the intervening period, all 55 U.S. states and territories enacted architectural licensure laws.

No state or territory has abolished the requirement for architects to be licensed, having previously created it. That said, some have come close.

In the late 1970s, for example, Alaska’s state legislature passed a sunset clause that required its architecture licensing board to justify its role to policymakers. The board survived in part by altering its composition to replace one of its architect seats with a member seat. Elsewhere, Kentucky’s board faced deregulation attempts four years after its 1930 founding, while the boards of New Hampshire and Nebraska faced sunset reviews in 1980 and 1984, respectively.

Of all the states to have faced the potential abolition of their architectural licensing systems, California is by far the largest. The effort, which took place in the late 1970s, has left a lasting impact on how the state licenses its architects today, even if its story is not well known.

The skepticism of licensing sewn during Reagan’s Republican governorship was continued and expanded upon by his Democrat successor, Jerry Brown.

The first signal that California’s architecture licensing system may find itself under threat came in 1967. That year, then-Governor of California Ronald Reagan named Caspar Weinberger as chairman of the Commission on California State Government Organization and Economics, known popularly as the Little Hoover Commission. Established in 1962 and still in operation today, the commission describes its role as to “make recommendations to the Governor and Legislature to promote economy, efficiency and improved service in state operations.”

A 1985 Los Angeles Times article quotes a letter Weinberger sent to then-Gov. Reagan in 1967, following his Little Hoover chairmanship appointment, in which Weinberger expressed skepticism over both proposed and existing licensing boards in the state. “Protection of the public is the only justification for business or professional licensing and regulatory boards,” Weinberger wrote, adding that “based on that criterion, none of the new groups seeking to be licensed in the Legislature this year meets that test, and several existing licensing boards should be abolished.”

Weinberger would go on to become chairman of the Federal Trade Commission in 1970 and President Richard Nixon’s director of the Office of Management and Budget in 1972. When Reagan was sworn in as President in January 1981, he appointed Weinberger as Secretary of Defense, a role he would resign from in 1987 before ultimately being indicted on charges related to the Iran-Contra Affair.

From reports at the time, it does not appear that architecture was among the licensing boards identified for abolition by Weinberger’s Little Hoover Commission. In fact, 1963 saw California strengthen its architectural licensing laws by making the practice of architecture by an unlicensed person a misdemeanor. Architectural immunity would change in the 1970s, however, when the skepticism of licensing sewn during Reagan’s Republican governorship was continued and expanded upon by his Democrat successor, Jerry Brown.

Jerry Brown served as Governor of California twice: First from 1975 to 1983 and again from 2011 to 2019. As early as 1977, Brown began making moves to reform state licensing boards, placing 60 members of the public on previously professional-dominated licensing boards, describing his new appointees as “lobbyists for the people.” An article on the initiative, published by The New York Times in 1977, described Brown’s view that professionals such as planners and lawyers held too prominent a role in government when compared to the general public.

“Citizen or lay participation in the affairs that have been arrogated to the guild of the professionals is a movement that is occurring in California,” the article quotes Brown as saying. “I don't minimize professional competence or specialization but along with that I would like to see — and I'm confident that it will occur over the next decade — increasing realization that there are certain human questions that cannot be passed off on to the professionals.”

This was not an isolated remark. The same New York Times article quoted a separate comment from Brown, also in 1977: “As the citizenry demands change and openness, the power and mystique that the professionals have been able to gather to themselves will weaken, and I think that should be a good thing.” Meanwhile, in an address to the aforementioned 60 citizens appointed to various licensing boards that year, Brown said: “It's only through the process of challenge and criticism that we made progress in the society. Some of these boards may not make any sense. If they don't, I'd like you to come back in six months and tell me whether they should be abolished or not.”

As the citizenry demands change and openness, the power and mystique that the professionals have been able to gather to themselves will weaken, and I think that should be a good thing. — CA Gov. Jerry Brown

One year later, Brown’s efforts escalated. In 1978, Speaker of the California State Assembly Leo McCarthy led a task force appointed by the State’s Department of Consumer Affairs, which examined over 20 licensing boards and commissions to determine whether they should be reviewed or abolished. According to the same 1985 Los Angeles Times article that quoted Weinberger’s letter to Reagan, McCarthy’s task force concluded that most boards should face sunset legislation, setting deadlines for the boards to satisfy legislature concerns or be disbanded.

Among the boards targeted in McCarthy’s task force was the California State Board of Architectural Examiners (CSBAE), which oversaw architectural licensure at the time. The task force recommended that sunset legislation should be used to abolish the CSBAE, effective June 30, 1980. An excerpt of the task force’s report on architectural licensure said the following about the CSBAE:

“As constituted, the Board...provides virtually no public protection through its existing function. Its licensing requirements are discriminatory and certainly excessive and their value, insofar as State regulatory interests are concerned, seems negligible. The Board's main function is to support the profession of architecture in California by protecting title and entry into that profession.”

Then-NCARB President Paul H. Graven expressed concern over the planned abolition of the board in a speech to the council’s Annual Business Meeting in 1978, describing it as “an alarming political development” and questioning whether NCARB or the CSBAE were given any opportunity to defend their role or purpose. Graven’s speech also noted that NCARB was made aware of the development not from the CSBAE but from a “very worried California architect” who had seen the story on the front page of the Sacramento Bee. Asked about this era recently, NCARB told me that the organization shared a tense relationship at the time with the CSBAE, who had begun to “not actively participate in national meetings.”

I don't think Brown understood what a hornet's nest he had stirred up. — John Parman

In 1979, McCarthy’s proposals were adopted by Gov. Brown, who formally proposed abolishing or phasing out 15 professional licensing boards. Many of the boards targeted were those first identified by Reagan’s Little Hoover Commission, while added to the list were the boards licensing tax preparers, geologists, and architects. Boards exempted from the proposals included law, medicine, and engineering.

“[Brown] argued that requiring registration or licensing, and having these boards, was basically self-serving and therefore the process should be privatized,” architectural writer and editor John Parman told me recently. Parman graduated with a Master's in Architecture from the University of California, Berkeley in 1975 and was part of an AIA California group formed to fight Brown’s efforts. “[Brown argued that] there's no valid health, safety, welfare or consumer protection argument, and that it's restraint of trade because people who would otherwise struggle to enter these trades or practices could just do so. They could just set up and do it, get a business license, and off you go.”

“It was not a big part of this program,” Parman added. “He was very young when he was governor the first time, and I think he was pretty full of himself too. I don't think Brown understood what a hornet's nest he had stirred up.”

As architectural licensing had been established in California in 1901 through state legislation, the abolition of state licensing similarly required that legislation be passed through both the California State Assembly and California State Senate. “I got [the legislation] out of the Assembly because I was Speaker,” McCarthy said in an interview quoted by the 1985 Los Angeles Times article. “When they got to the Senate, some of the boards and commissioners wrote letters to every senator saying that I was trying to destroy them.”

As the legislation progressed to the State Senate, the targeted boards and professions began hiring lobbyists to persuade Senators to kill Brown and McCarthy's plans. “Usually they were second- or third-tier lobbyists,” McCarthy’s reflection continued. “The little fellow with two or three or four small clients. They would say to Senator X, 'This is my bread and butter. I've only got three clients, for heaven's sake.' A very human element came in. The senators felt sympathy for the lobbyists.”

Parman likewise remembers the lobbying effort waged to defeat the plans. “As soon as you threaten something with death, they fight like hell,” Parman told me. “And that's what happened. And of course, at the time, the legislature was quite open to being persuaded by the usual means that legislators are persuaded.”

To defeat specific plans to abolish state licensure of architects and the CSBAE, the AIA California Council formed a group of senior professionals to spearhead the lobbying effort. A recent architecture graduate, Parman worked for the group, which allied with the CSBAE to create a common strategy to defeat the legislation. As Parman recalls in a recent article, the group argued that architectural licensure was necessary to protect public health, safety, and welfare, just as it was for the engineering profession exempted from the legislation. To further underscore its purpose and relevance, the CSBAE also floated the development of a California licensure exam independent of NCARB to address regionally specific issues such as seismic activity and energy.

The efforts by Parman and others paid off. The sunset legislation died in the State Senate, and every one of Gov. Brown’s efforts to abolish state licensure, including that of architects, was defeated.

As soon as you threaten something with death, they fight like hell. — John Parman

While the CSBAE survived abolition efforts, the board’s relationship with NCARB remained fragile. The CSBAE would later follow through with its proposal to develop its own exam in place of the ARE, leading to the 1987 launch of the California Architect Licensing Examination (CALE). In September 1987, the same California Legislature that had considered the abolition of state licensure less than a decade previous passed a law that only permitted reciprocal licensure to architects whose home states declared the ARE and CALE as equivalent. As the measure contravened NCARB’s bylaws requiring all licensing boards to administer the ARE, a standoff ensued between the two bodies.

By the turn of the decade, however, relations between NCARB and the California board were resolved. Lengthy negotiations led to California once again administering the ARE from June 1990, with provisions established for architects who passed the CALE and sought NCARB certification. In 1999, the CSBAE was renamed the California Architects Board which still oversees licensure in the state today, while the CALE would evolve into the modern California Supplemental Examination (CSE) that current licensure candidates in California are required to pass in addition to the ARE.

Meanwhile, Gov. Brown’s relationship with licensure boards has undergone its own evolution. While Brown’s first stint as governor in the 1970s included an attempt to abolish or phase out over a dozen licensing boards, Brown’s second stint included signing a law in 2014 that prohibited the denial of licensure applications based on citizenship status or immigration status.

Four decades after Gov. Jerry Brown’s efforts to sunset licensure failed, a similar effort succeeded in, ironically, the Sunshine State of Florida. In June 2020, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the Occupational Freedom and Opportunity Act into law, which relaxed or eliminated regulations on the entry into various professions. While architects were not impacted by the law, landscape architects saw reductions in protections on their licensing. Interior designers similarly saw all licensure provisions removed, though certification remains allowed on an optional basis.

Architectural licensure may have survived Brown’s abolition efforts and escaped DeSantis’ agenda, but when taken together, the two episodes highlight how moves to abolish professional licensure can reach across time and across the country. History, too, demonstrates the potential for such moves to arise on both sides of the political aisle, from a Republican Ron DeSantis administration in Florida to a Democrat Jerry Brown administration in California, inherited by his Republican predecessor Ronald Reagan.

The political influence and ambition of the figures who have taken interest in such efforts should also not be understated. Gov. Reagan would become U.S. President, and Weinberger his U.S. Secretary of Defense. Gov. DeSantis was once described as the future of the Republican Party, while Gov. Brown, the longest-serving governor in California’s history, sought the Democrat presidential nomination in 1976, 1980, and 1992.

The two episodes highlight how moves to abolish professional licensure can reach across time and across the country.

“Governors of all stripes find it attractive to campaign on a populist platform,” NCARB CEO Mike Armstrong told me in a recent conversation which reflected on such efforts to relax or abolish licensure. “I think we're in an era now where it is imperative that we on the regulatory side restate our value to the politicians in this country. We can't just assume that it's always been this way and it always shall be this way.”

“We are in a perfect storm where politicians on the left are concerned about regulation as an impediment to inclusion and accessibility into professions,” Armstrong added. “Politicians on the right are concerned about the chilling effect on our economy that regulation can have. So there's arguably a bipartisan consensus toward regulatory reform.”

As part of its efforts to convey the importance of state licensure to public officials, NCARB has conducted public polls of voter’s opinions on licensure and regulation. Summarizing the findings, Armstrong told me that approximately two-thirds of the voting public say that regulation is important, while over 90% believe that licensure for architects is important.

“There is still a public awareness that there are certain jobs that do protect you and that a license is a contract between you and the public you serve,” Armstrong noted. “But we need to also demonstrate that we can evolve and reform and streamline when necessary.”

Editor's note: this article originally said that landscape architects in Florida lost all title protections under the Occupational Freedom and Opportunity Act. In fact, the title is still protected, but the law: "Removes examination requirements for landscape architects applying for endorsement, requiring only that they hold a license by another state or U.S. territory," as well as "Eliminates separate business licenses for architects, geologists, and landscape architects who already hold an individual license in order to remove unnecessary barriers to entry."

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

8 Comments

This comes up quite a bit.

Can we speculate on what would be like if all states' architectural licenses were abolished in the '60s? One of my speculations would be, that architecture is only designed by huge conglomerates, who can afford some kind of compensation if anything goes wrong. The design and meaning of architecture would be long modified as the mass product that comes with options on the trim. The education of the architects would be limited to operational job readiness, etc. But the biggest bang would be around the highly polluting and 'wrong' city vistas and floor plans. My view is kind of bleak.

I am interested in positive views and sceneries if offered here.

Would then developers form their own architecture in house offices? Would professional wages drop to pennies? Would architects remain as the coordination core of projects? Would most architecture offices still consider licensing a valuable asset in candidates' resumes?

Also, i believe that in Florida landscape architecture is still a licensed profession

This article raises two issues: 1) what value does registration bring to practice?; 2) what value does an architect bring to construction?. These are cultural questions more than legal ones as the redundancy and specificity of codes makes the "life and safety" issue virtually moot today. And NCARB's argument for licensure is largley limited to those three words. Then the ages-old problem of "public awareness".

"...NCARB ... conducted public polls of voter’s opinions on licensure and

regulation...[in which]...approximately two-thirds of the voting public say that regulation is

important, while over 90% believe that licensure for architects is important."

Polls are interesting things: they are instruments with the appearance of precise scientific infallibility and neutrality, but even a sterile petri dish can be contaminated before its swabbed. Presuming NCARB's poll had validity, I'd be interested to know what percentage of that two-thirds and "over 90%" have, or would ever hire an architect for even a domestic project let alone a small commercial building. I live in a neighborhood in which lots under a 1/4 acre sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars upon which 2 million dollar houses are built. They are largely the work of contractors using standard "designs" made by...who knows. Soon, Ai.

Even decent-sized commercial projects are built absent an architect as contractors can use use an engineer to seal a project for a nominal fee.

There have always been only a tiny fraction of people outside of architecture culture who value the work of an architect or even understand what one does. It's been that way since before NCARB existed. So, one wonders how would that be factored into the value of NCARB's opinion of its own value?

"Even decent-sized commercial projects are built absent an architect as contractors can use use an engineer to seal a project for a nominal fee."

What is considered a decent sized commercial project?

What states allow an engineer to sign architectural CD's?

I'm genuinely interested in this!

Not a surprise that California single family housing spawned much of the most creative design innovation as they aren't required to be architect stamped. Many states still allow single family housing or small buildings to be approved without architects, which is probably why multifamily buildings are so expensive.

Architects made a Faustian bargain to serve themselves, not the public.

Single family housing sprawl in California probably has more to do with the large amount of available land at the time. I don't think having non architects design the homes had much to do with it.

Multifamily housing is costly to build because of the materials and code requirements. It's not because an architect is involved.

A very good article that raises various questions about the legal mandate of architects and the ways it is, or should be protected. Food for thought for professionals.

But it also raises questions about the cultural mandate of architecture and its broad acceptance among society. Food for thought for creatives, for example when they ponder what they want to do with their lives. Or for historians who want to ponder in what sense architecture contributed to a civilization. Or in which degree it still does.

For the latter, besides the question of legal protection, there is always the legacy of 1000s of years of architecture that may help to understand the surplus value of the rare intelligence called architecture. But for the first, only the contemporary degree of vision, vitality and vibrancy among practitioners to express, defend and enhance their unique skills “in the interest of the public”, should be the sine qua non of any “protection” that goes beyond the self interest of the “bread and butter” argument.

What energy could architecture summon at the next Jerry Brown at the horizon?

This is actually where a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of insurance and liability permeates and remains unspoken. If one looks at the architectural contract and negotiation process, there is a significant role that insurance coverage and liability plays in the delineation of what an architect is "responsible/liable for" versus what a developer or contractor is "responsible/liable for". To not understand this is to turn this into a don quixote exercise of charging at windmills. Let me break it down like this:

A city receives documents from a licensed architect with professional insurance, the city reviews the documents and confirms they meet code requirements, but the architect is liable for the design's compliance to code. To remove the architect from this simple example means that either the city is accepting liability for the code compliance or the developer is accepting liability for this. Inherently most developers run on a proforma where they are minimizing overhead to cover soft costs and defraying any significant expenditures until construction begins so those costs can be covered by the construction loan, as any money to cover prior to that is provided by investors or the firm, meaning it is expensive cash...not cheap cash (construction loans are typically a low percentage on the construction costs, whereas preconstruction/investor investment is high percentage on the money provided)....therefore accepting liability is not the basis of this type of model. In addition insurance for ownership is complicated and expensive enough without taking on the liability of code compliance by architectural professional insurance. The other potential recipient of liability and insurance would be the city, and that is significant exposure....which they wouldn't accept for the same reason the developer doesn't want it.

So, (for once) our litigation based system actually is protecting the value of the architectural profession. The reason you see non-professional acceptance of liability on houses is because of the minimal liability to outside groups because of private use...but any place that is used by the general public or involves multi-story, multi-family residential use by people who do not own the asset or co-own the asset or even is used extensively by individuals that can sue the owner for issues creates a massive liability....hence why professional licensure and insurance is required at a level to cover the project.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.