In a confluence of events, the autumn of 2021 saw the opening of both the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow and Expo 2020 in Dubai. While COP26 is billed as "the last chance saloon" to save the planet, Expo 2020 Dubai is described by its organizers as "the most sustainable expo in the history of expos." This opinion piece reflects on how beneath Expo 2020 Dubai's rhetorical and programmatic accolades, the event is in fact a symptom of a systemically unsustainable attitude towards the built environment and a warped exercise in utopian thinking.

After $7 billion of expenses, eight years of planning, and a 12-month COVID-induced delay, Expo 2020 Dubai is finally underway in the United Arab Emirates. Operating under the theme “Connecting Minds, Creating a Future,” the event uses the three sub-thematic pillars of sustainability, mobility, and opportunity to speculate on the future of the built environment, and to showcase technological, cultural, and societal change.

In a move echoing much of the region’s urban transformation in recent decades, this new challenge saw Dubai turn to new land. Between the project’s commissioning in 2013 and its opening in 2021, more than 1.7 square miles of empty desert was overlaid with an urban master plan designed by HOK and delivered by AECOM. The master plan features three districts representing Expo 2020’s three sub-themes, all anchored by a 220-foot-tall centerpiece dome designed by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture. Each thematic district is itself anchored by a flagship pavilion. While Foster + Partners’ Mobility Pavilion celebrates the boundless possibilities of travel both across and beyond Earth within a curvilinear structure, AGi Architects’ Opportunity Pavilion uses the concept of a ‘plaza’ to shape a sharp, cantilevering gathering space. Finally, Grimshaw’s Sustainability Pavilion seeks to showcase the latest in environmentally-friendly energy production across its flower-petal form, with a collection of “Energy E-Trees” providing 28% of the building’s power through rooftop photovoltaics.

Even among the 170-year history of the World’s Fair, Expo 2020 has still managed to set records. The first World’s Fair to take place in the Middle East, Expo 2020 has seen a record 191 countries participating in the event, with each participating country hosting their own national pavilion for the first time. Reminiscent of the Venice Biennale format, the allocation of individual national pavilions has led to a portfolio of unique structures showcasing the cultural roots, artistic outlooks, and scientific contributions of each nation, many of which have been shaped by the world’s most acclaimed architects and designers.

The Es Devlin-designed UK Pavilion, for example, uses a conical CLT structure to celebrate advancements in artificial intelligence, material science, and sustainability in food and fashion. The Santiago Calatrava-designed Qatar Pavilion, meanwhile, echoes the Qatari coat of arms through a curvilinear structure within which the country can showcase its radical future development goals. Calatrava’s other contribution, the UAE Pavilion, is equally grounded in symbolism. Through its adoption of a falcon’s mid-flight shape, the pavilion is defined by 28 folding, moveable mechanical wings, sheltering an internal space also dedicated to showcasing the country’s future urban visions. Even the entrance to the Expo 2020 site is steeped in cultural cues, with the Asif Khan-designed Expo Entry Portals drawing inspiration from the latticework of traditional Arabic dwellings, creating a set of three 70-foot-tall gateways made from a lightweight carbon fiber composite.

...the underlying premise of Expo 2020 Dubai is in-fact a demonstration of our failure to take climate change seriously.

While the architectural extravagance on display at Expo 2020 has understandably captured the headlines and imaginations of the world’s media, so too has the event's strong emphasis on sustainability. As world leaders descend on Glasgow for a COP conference billed as our “last chance saloon to save the planet,” Expo 2020 offers a real-world measure of how human technology, and the human mindset, are actually equipped to combat climate change. “We aspire to deliver one of the most sustainable World Expos ever,” noted the event organizers on their site. “It may seem like an ambitious goal, but sustainability is ingrained in everything we’ve been doing, from buildings and construction to establishing a lasting legacy long after Expo is over.” In their glowing review of the event, titled “A World-Class World Expo,” The New York Times heaped praise on the event for what it called a “focus on the future of the planet,” listing a litany of examples from Morocco’s rammed earth pavilion to the Expo's use of solar farms and water recovery.

By identifying sustainability as a key pillar for the entire event, Expo 2020 Dubai set itself a tall goal, and arguably, set itself up for failure. Despite its well-marketed sustainability credentials, the climate-conscious panels, events, and exhibitions it hosts, and even a leading Expo official declaring to The New York Times that “this is the most sustainable expo in the history of expos,” the underlying premise of Expo 2020 Dubai is in-fact a demonstration of our failure to take climate change seriously. Of the 200 pavilions constructed from scratch at Expo 2020, only seven have achieved a LEED Platinum rating; the highest environmental rating offered under a system which has itself been criticized for being too lenient on environmental standards. A vast majority of the buildings constructed at Expo 2020 are instead certified with the lower-rated LEED Gold, a performance which cannot be considered acceptable for a built environment constructed with no existing urban constraints, at a time when our ability to understand, measure, test, and construct LEED Platinum-level buildings has never been stronger.

Does the construction of any 1.7-square-mile temporary city across a barren desert make sense in our universally-declared mission to combat climate change?

Among Expo 2020’s LEED Platinum buildings, there was also room for skepticism. Shortly after its opening, Grimshaw’s Sustainability Pavilion was criticized by leading construction sustainability expert Simon Sturgis for its embodied carbon footprint of 18,000 tons, which is double the recommended level for a building of its scale. Sturgis took particular aim at the pavilion’s Energy E-Trees for their “significant unnecessary emissions” due to their large scale and reliance on concrete and steel. Noting that the pavilion carries a carbon footprint comparable to a typical new multi-story office building, Sturgis concluded that “this design is not where you would start if you wanted to make a truly sustainable Sustainability Pavilion.” The critique of the Sustainability Pavilion prioritizing environmental style over substance even seemed to be tacitly conceded in The New York Times’ glowing review of the pavilion, passively referencing the project's disappointing embodied carbon performance while nonetheless praising the design as “a showstopper.”

Beyond the micro-analyses of building performance and accreditation, there is a broader unsettling question to be asked of Expo 2020: does the construction of any 1.7-square-mile temporary city across a barren desert make sense in our universally-declared mission to combat climate change? Despite the organizers’ intention that the site for Expo 2020 will continue to play an active role in Dubai’s urban fabric for decades, it remains the case that most national pavilions will be dismantled following the event’s conclusion in March 2022. This casual approach to temporary new construction comes despite warnings that 50% of emissions from new buildings are emitted via embodied carbon before a building is ever brought into operation, that 40-50% of globally extracted resources are used in construction, and that building materials account for half of solid waste generated every year worldwide. Through their failure to radically reform what urban development means in the context of climate change, Expo 2020 can instead be reduced to a 1.7-square-mile example of “do as I say, not as I do,” built within a nation which draws 30% of its gross domestic product directly from the output of oil and gas.

Expo 2020 Dubai is first and foremost an exercise in realizing utopia; of taking remote, empty land as a blank canvas to overlay an idyllic picture of civilization.

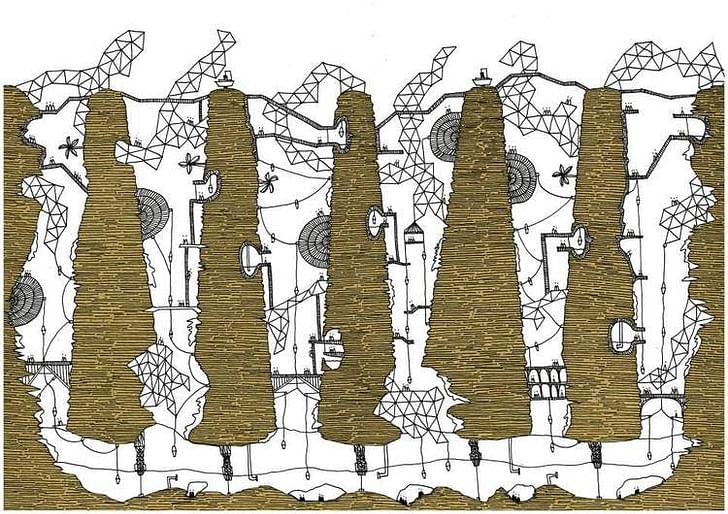

Far from being driven primarily by a genuine desire to combat climate change, Expo 2020 Dubai is only the latest chapter of a worldwide obsession among wealthy governments, investors, and institutions of shaping physical environments to showcase power and prestige. From tech moguls seeking to turn American deserts into starchitect-designed metropolises, to 100-mile-long linear cities proposed in Saudi Arabia, Expo 2020 Dubai is first and foremost an exercise in realizing utopia; of taking remote, empty land as a blank canvas to overlay an idyllic picture of civilization.

This exercise is not dangerous by default. In fact, the concept of ‘utopia’ is one which frequently intersects with architectural education and theory, most notably through seminal texts such as Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, William Morris’ News from Nowhere, and of course, Thomas More’s Utopia, from which the term originated. The three books, written in three separate centuries, have long been used as tools within architectural education to impress on students the value of departing from a status-quo, as well as the relationship between a society’s values and the built environment they subsequently shape. The value of utopian thinking in architecture was even the topic of a 2016 debate at the Royal Academy in London, where architect Ian Ritchie declared: “I believe in the value of utopian thinking, and as an architect, I am driven by an ambition to synthesize poetic and philosophical thinking to realize my dreams and visions of a better future.” Reflecting on the undercurrents of optimism, hope, and alternative processes which embody utopian thinking, Ritchie sees utopia as “a set of principles to guide an exploration of architecture, and a committed plea for a lived reality using social understanding, innovation, and technology that can lead to better futures for societies worldwide.”

Rather than be used as evidence of the flaws of utopian thinking, Expo 2020 should act as an impetus for architects to revaluate our vision of an idyllic society.

While 21st-century exercises such as Expo 2020 Dubai align themselves with the goal of using social understanding, innovation, and technology to create better futures, the Expo’s manifestation of this goal highlights the extent to which today’s interpretation of utopia is divorced from that of Calvino, Morris, and More. Where Calvino dreamed of cities deeply in rhythm with nature, with urban development guided by water and star constellations, Expo 2020 embodies our lack of respect for the natural world, whether through the vain supplanting and reconstruction of alien ecosystems, the mining of natural resources for temporary pavilions, or the questionable environmental performance of the pavilions themselves. Where Morris dreamed of a human-centric environment without large cities, where humans could find pleasure and beauty in nature, Expo 2020 sacrifices the human scale in favor of imposing artificial monuments to technological and cultural prowess, where nature is displayed, implied, and subjected but never a governing entity. Meanwhile, despite More’s untenable acceptance of slavery and sexism in Utopia, his open willingness to dismiss 16th-century British society as a “conspiracy of the rich” sits in contrast to Expo 2020, an event which The Economist argues “strives to gloss over politics,” where exhibitors are instead “able to present Panglossian visions of themselves to investors and tourists.”

Rather than be used as evidence of the flaws of utopian thinking, Expo 2020 should act as an impetus for architects to revaluate our vision of an idyllic society. In the context of climate change, global and local inequalities, and increasing social and political divisiveness, it is necessary for those who propagate notions of utopia to ask how utopian worlds can still capture the public imagination while legitimately and effectively contributing to the tackling of real-world problems. Rather than dreaming of new cities in a Nevada desert, should architects instead focus their utopian energy on existing cities in urgent need of repair, such as economically-stricken Detroit? Rather than facilitating an idyllic, temporary, imposing, $7 billion cityscape in Dubai in the name of combatting climate change, should architects instead be advocating for the adoption of radical, permanent, holistic urban interventions for the 2.4 million people living in existing slums in Karachi, whose living conditions place them at an augmented risk from said climate change?

Expo 2020 Dubai is not the sole perpetrator of our lost understanding of idyllic urbanism. As we have reflected on in previous feature pieces, large-scale events such as the Olympic Games continue to rely on the creation of new urban environments to host events lasting months, or perhaps only weeks, but at a considerable, permanent, environmental cost of carbon emissions through construction and a social cost of displacing established communities. Within architectural circles, there is also a growing uneasiness over the environmental impact of curatorial events such as the Venice Biennale, with critics such as Carolyn Smith noting that the Biennale’s “reliance on temporary, bespoke installations — and the absence of a sustainability agenda from the Biennale Foundation to aid with recycling or reusing materials — is completely out of step with the global shift towards the careful use of resources.”

This isn’t how the future of urbanism needs to unfold.

These events continue to propagate a dangerous view of what human progress in the built environment looks like; one which implicitly views the built environment, however small, as a disposable asset, and either ignores or inadequately responds to the environmental impact of extracting, processing, transporting, constructing, and disposing of temporary structures every two, three, or five years. This isn’t how the future of urbanism needs to unfold. Humanity can showcase and propagate visions for the future without relying on the wasteful construction of vast physical vessels to do so. Dubai can urbanize in a sustainable, holistic fashion without relying on the rapid development of arenas devoid of an everyday human scale. Buildings can offer a neutral, or even positive relationship with the natural environment without sacrificing artistic flair, financial practicalities, or human needs.

Meanwhile, architects, governments, and citizens can continue to speculate on what utopia means in the 21st century; a question which is now less of a hypothetical exercise among scholars and artists but an increasingly necessary ambition amid increasingly dire climatic circumstances.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

6 Comments

A depressingly accurate assessment of the whole gaudy spectacle. Unfortunately, there still doesn't seem to be much glory or gain to be had from addressing quotidian, human-scale societal needs.

There is a lot of hard work on the policy level that such spectacles gloss over. What these pavilions and speeches could do is to excite the imagination and showcase technology and behavioral advances that could help alleviate the climate crisis. Kind of like the Expos of yore, before the internet made the world smaller. Unfortunately, the amount of material waste being pumped into this event is a damning indicament, and the buildings really don't seem to inspire excitement like their predecessors had.

Expos such as this should be set up to provide needed buildings long term, affordable housing, schools, etc… instead it’s just a corporate marketing / political propaganda exercise with no practical future use. Why supposedly “sustainable design” leaders participate in such obvious farces shows how architects continue to kowtow to our corporate overloads, disgraceful

Great piece. It is too bad that a lot of other Global publications (apart from the Economist, that you pointed out) have not written much about this mega-money fuck fest.

This is the most depressing thing I've seen all day. And I saw a cat with a facial deformity. Ridiculous.

Thank you for writing this. I'm sure you'll get a lot of grief from the starchitect worshippers out there, but enough is enough of this ridiculousness.....

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.