For Miriam Hillawi Abraham, the digital realm is one fraught with both opportunities and dangers. The Ethiopian designer and researcher sees digital media as an impactful, playful, and unrestrained way of shaping immersive stories that challenge Western narratives and power dynamics imposed on the African continent, its histories, its built environment, and its people.

Meanwhile, Abraham sounds a timely note of caution on the potential for digital technologies and artificial intelligence to generate a single, incomplete visual language for the future, further propagating a Western-centric monoculture under a false guise of democratization, opportunity, and accessibility.

In July 2023, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Abraham about her life, work, and reflections on the relationship between architecture, storytelling, digital realms, and power relations. The discussion, edited slightly for clarity, is published below.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

Niall Patrick Walsh: Could we start with an introduction to you and your work?

Miriam Hillawi Abraham: I am a multidisciplinary designer and researcher based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where I was also born and raised. My architectural career began with a BArch from the Glasgow School of Art. I found myself deviating from the traditional architectural path after this, though; that said, my work still remains rooted in architecture and the exploration of belonging and territory.

A few years ago, I completed a Master of Fine Arts in Design at the California College of the Arts, where I set out with the goal of merging architectural practice with other processes, such as industrial design and creative computation. Through this study, I recognized the potential for designers to work outside of the prescribed industry silos that are often propagated in architectural education. It was at this time that I began to explore the questions and topics that are now central to my practice, using channels such as speculative fiction, experiential design, radical imaginaries, and multiple futurisms. I’m working outside of the learned methods of architecture but am still in dialogue with them.

I’m working outside of the learned methods of architecture but am still in dialogue with them. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

As you say, there are many composite elements to your work, particularly the blending of architecture and design with computation, narratives, and storytelling. How did these two themes of storytelling and digital media come to the forefront of your career? Were they longstanding interests that predated your design education, or did they emerge later?

It was both. Storytelling was central to my childhood, especially myth and oral histories in our family, which, as they pass from one generation to the next, become more and more fantastical. Over the years, storytelling has become my tool for intervening in certain normative systems, and something I’ve always sought to merge with architecture. I found there to be some resistance to that in my initial architectural education, which was more technical. I was interested instead in the ‘livingness’ of a building, or the space that a building encloses or creates around it through the activities and stories that unfold there. I would ask: "What stories or events haunt the building, or the space that the building now occupies?"

I wasn’t designing in a plan view, or from a god’s eye perspective but rather from the perspective of an experience or a story. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

Meanwhile, digital media became an unexpected way for me to think about how I could explore these questions without necessarily physically intervening in a space. Here, I could antagonize, question, or be in conflict with certain ideals, but in a gentle, distanced way, as if I were masking it in satire and play.

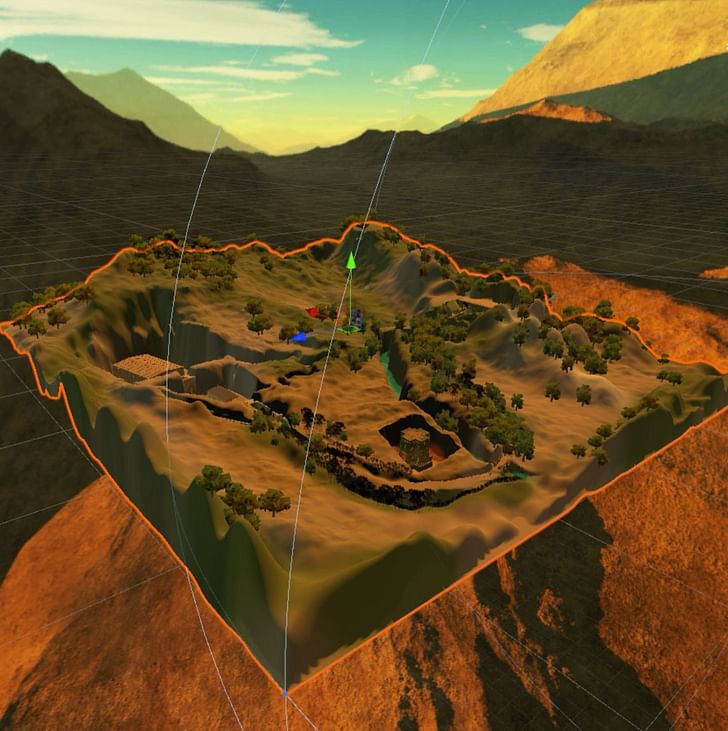

During my Masters, I began exploring the idea of virtual reality, which led me to unlearn many architectural processes and thinking. All of a sudden, I wasn’t designing in a plan view, or from a god’s eye perspective but rather from the perspective of an experience or a story. I was driving the space around an interaction. As part of this, I learned about game design as a way of both forming space and creating enactivism. Having someone play or embody a certain character was far more impactful to me than just creating the building and expecting that to create change in itself.

As you say, these mediums of storytelling and the digital are part of a wider mission in your creative practice. When describing your mission, you talk about deciphering and conserving oral histories and disappearing knowledge systems from across the African continent, and striving for their continuation into the digital future. You also talk about how “Blackness has been historically banished to the margins and the realms of the exotic,” and how “the politics of design and space-making emboldens us to reinforce Black subjectivity and claim uncharted territories, asserting and centering ourselves in multiple futures.” Can we unpack this mission a bit more?

As you mentioned, it is about continuing or expanding beyond the histories or timelines that were severed and interrupted by colonialism and imperialism on the African continent and her diaspora. For a continent and a people that have historically been represented as external to modernity, a site for reckless extraction, and as a canvas onto which to project dreadful market-driven, ecocidal, and turbulent futures, these methods can allow us to regain mastery of our own future and authority over our past/heritage. I also seek to unsettle formal historical and architectural canons by hacking them or intervening between them through overlooked perspectives, especially those of the subaltern or bodies that have been overshadowed or marginalized in the conception of space and collective histories.

Overall, my work is driven by the idea of using storytelling and world-building to approximate realities that are not necessarily ideal, perfect, or utopian but instead disrupt our dysfunctional present and allow us to consider multiplicities and alternatives so that we do not merely exist as passive subjects to our futures. This work is lifelong and ongoing, but hopefully, it will urge others to intervene and raise their voices among these branching ideas.

You made an instructive point earlier about how architects often design by looking down on a plan with a “god’s eye perspective,” and that you instead seek to understand space through embodiment and experience. I wanted to build on that and ask you about what your process looks like. There are so many strands to your work, including digital realms, storytelling, histories, and reflections on inequality and injustice. Is there a common process that you work through when translating these strands into a project, or does your process or methodology vary widely depending on the project?

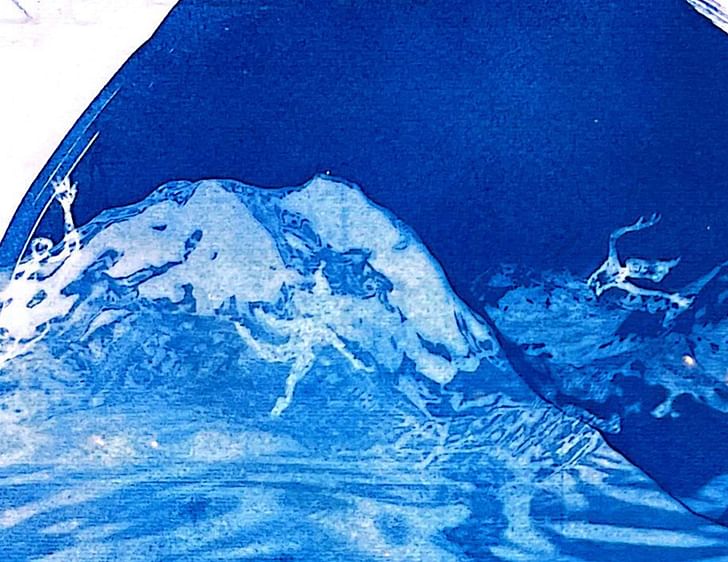

Over time, a common thread has emerged in how I approach projects. There is often the process of fictionalization, or taking a single aspect and expanding it into a territory or a myth. For example, I have been developing a research project with the Canadian Centre for Architecture called the Repository of Digital Cosmologies, where territory is represented by navigation and cartography. Here, we are drawing constellations between pre-colonial cosmology and spatial orders rooted in the African Sahel, from West Africa to the Horn of Africa to Ethiopia and Eritrea. By remapping these preexisting, ancient, nomadic cultures, and the way they use cartography, we can start to collapse established timelines and disrupt the monocultural Western worldview, bridging a mystical past with an elusive future.

My work is driven by the idea of using storytelling and world-building to approximate realities that are not necessarily ideal, perfect, or utopian but instead disrupt our dysfunctional present and allow us to consider multiplicities and alternatives so that we do not merely exist as passive subjects to our futures. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

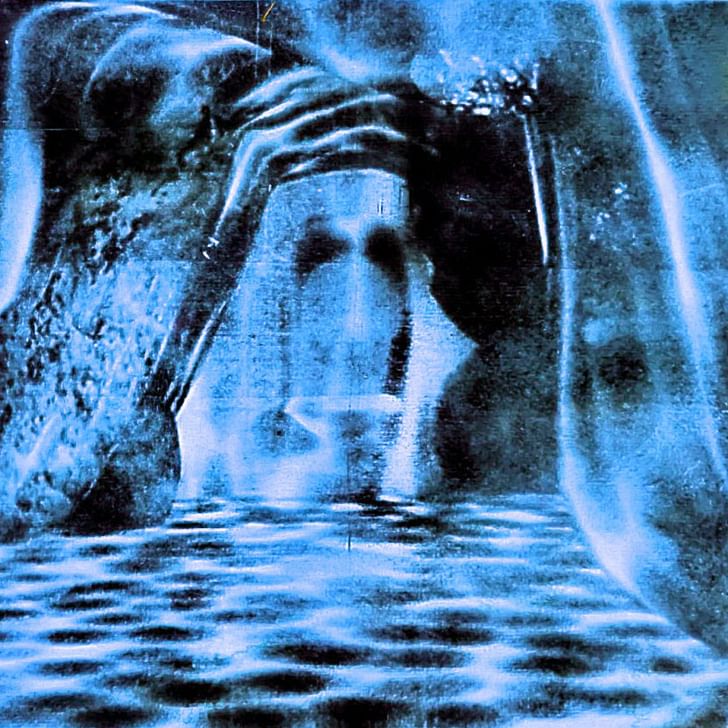

Another example is an ongoing collaborative mixed media project between myself and my friend Heejoon June Yoon called the Museum of Monstrology. Here, our interest in space and territory is represented through the body of what a normative culture would call the mythical monster. How cultures birth monsters, how they are intended as warnings, and how they subsequently morph the sites they inhabit in our imagination and dreams, are all subjects of research for us. We look at how monsters help us reconsider territory and belonging, and how in medieval lenses, the ‘other’ is represented as a monster; this transgressive figure who is beyond the scope of understanding or empathy of the colonial authority. As we contend with the threat of extinction and destruction of the planet, we dig for generative opportunities in the emergence of new organisms and the possibilities of what Fanon coined “radical mutation,” whereby bodies adapt in order to survive in hostile environments, be it social or ecological.

When the surface erodes, boils, and morphs, will these monsters come to the surface? Will we, in turn, morph into monstrosities to survive as the earth undergoes this change and undoing?

I want to also add to this list your project Abyssinian Cyber Vernaculus, which has been featured at the Guggenheim and the Venice Biennale. I found it deeply engaging when I explored it before this conversation, and it also intersects with everything we’ve discussed so far on digital storytelling, myths, histories, architecture, and colonial dynamics. Could you give us an introduction to the project as a whole?

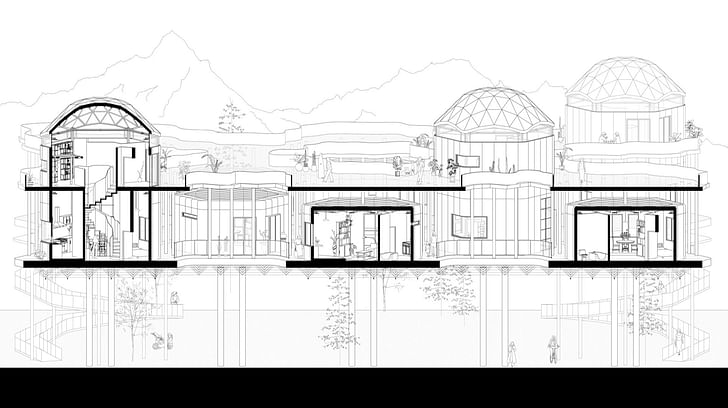

Abyssinian Cyber Vernaculus is essentially a series of visual narratives or stories that unfold over the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela in northern Ethiopia. It began as my thesis project at CCA, where it grew into an exercise of reimagination to bypass the hegemony surrounding Ethiopian material heritage, as well as the myths and folklore that obscure my view as an Ethiopian as I gaze into its mysterious past. This was my way of interrogating the presence of other cultures and actors in the site over time and how they directly influenced the architecture outside of the dominant local Orthodox Christian history.

Initially, the goal was to explore the area's contested past. To give some context, the site is comprised of eleven churches carved from. Unlike other monolithic structures, the construction is said to have been undertaken within 24 years or less, depending on different myths. More peculiar still, no debris has been found on the site, which is in contrast to other monoliths where significant debris would have been generated from excavation.

This all led to the complex being in limbo in terms of a discreet history. The sanctity of the space, the presence of UNESCO, and the bureaucratic order of conservation and tourism all prevent a re-imagining of the past as well as a sense of ownership of the site for me. The project therefore started with me trying to excavate alternative histories and stories that would have taken place or caused the complex’s conception.

This was my way of interrogating the presence of other cultures and actors in the site over time and how they directly influenced the architecture outside of the dominant local Orthodox Christian history. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

I began by targeting what I recognized as the three dominant perspectives of the site, which derive mostly from a patriarchal lens. There is a dominant conservative Christian ethos, a diasporic, Rastafarian perspective that doesn’t interrogate the impact of imperialism either, and finally, a Western academic or a ‘white savior’ that assumes authority over African artifacts and cultural production, which is also exemplified by how none of our artifacts have been repatriated from the British Museum or the Met.

These characters became the three antagonists, but rather than looking at them as antagonists, they operate as players that you can embody to move throughout the same site. Through following them, you go through a process of unlearning. As I mentioned before, this idea of play and enactivism allows for a gentle way of critiquing incredibly sensitive subjects, especially within the contemporary conditions of Ethiopia, where the concept of religious blasphemy and contending with histories of injustice of oppression are continually creating rifts and violent friction between communities.

The story actually started as a set of comic books, but over time, they developed into a virtual, interactive experience. It is fascinating to see which characters people have an affinity for when they begin, how they move through the experience, or how they might feel personally attacked by a character’s journey. Virtual reality became this useful non-extractive medium for me to engage with. Even now, virtual reality remains an unchartered, non-formalized technology in which we are free to make claims and to use for world-building without it becoming overly consumer-driven.

For me, Abyssinian Cyber Vernaculus as a whole becomes an act of architectural transmutation that slips past the strict barriers of the physical and bureaucratic to reach the imaginary. By planting false stories or false evidence in the context, I am able to redirect Lalibela’s original history as well as open up multiple questions and channels of existence for the site itself. The architecture bears witness to the stories and, unlike in the physical realm, is able to resist ruination and extend its life into the digital.

Can you offer an insight into how you constructed this environment in virtual space? It must have been an incredible undertaking to reimagine this complex and to balance the use of recorded information about the site with a mission to break free of it in some ways.

It was a massive investment of time. Originally, I approached the project from the perspective of architecture and sought to represent the site in as true a scale, form, and history as possible. I soon realized how difficult that task would be but also began to think critically about conservation. I would ask: “What aspect of the history are we conserving?” If I stay true to the present, I would be forced to model the horrible interventions that UNESCO installed and forgot about over the past twenty years. What aspect of history was I idealizing? These questions allowed me to liberate myself from the established realities or accuracies, and instead embrace a degree of error.

There is the illusion of completeness in a world that is never complete. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

I also realized that architectural software such as Rhino and other CAD systems do not lend themselves to game engines such as Unity, which I would have to use for VR. I subsequently moved to a new software, Blender, which revolves around sculpting. Rather than extruding forms from a negative into a positive, you are actually ‘excavating’ your forms in the digital space, which I found to be more representative of Lalibela itself, where buildings were excavated and carved rather than constructed on the land.

With game design, you also are not designing an intricate, complete model for a historical society. You are designing for the experience of your player, which means you can use tactics such as 2D billboarding to extend the player’s universe without allowing them to touch it. There is the illusion of completeness in a world that is never complete.

Given your engagements with Black subjectivity, histories of racial and cultural discrimination, and the interrogation of homogenous Western perspectives being pushed onto the wider world, I wanted to ask you about the recent popularization of artificial intelligence tools and systems. Many of the central themes of your work are also subjects of concern in AI, such as bias, ownership, accessibility, and monocultures. What are your thoughts on these concerns? Conversely, do you see AI becoming a tool in your own process?

With these technologies, it is important for me or anybody engaging with the same topics as me to claim these tools before they are, in turn, used to represent us. We must avoid a repeat of what happened with the early development of the camera, for example, which was used to create this idea of the exotic ‘other’ and drive an ignorant view of civilization. It is important that we use these tools but also recognize that they are not necessarily going to help us dismantle the discriminative or prejudicial systems I am talking about. We in the Global South were not the intended users. We were not central to the conception of these tools in Silicon Valley. Instead, we on this continent are cornered into a subservient role to this empire, whether extracting materials such as lithium or sand, being a center for manufacturing/labor, or being mined for data.

We in the Global South were not the intended users. We were not central to the conception of these tools in Silicon Valley. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

As a result, we inherit a faulty tool and a broken system that often presents itself as an ambivalent or neutral solution to our most pressing problems. We hear empty ideas such as “cryptocurrency for Africa” without any attempt to address what it means, or how it is playing out in the places it was developed. Ruha Benjamin and Timnit Gebru both make strong points about how new technologies are already reproducing existing inequalities even while being promoted as objective or neutral.

Specifically on the subject of digital archiving and conserving architectural heritage through digital means, Mohrehsin Allahyari’s warnings about Digital Colonialism and digital sovereignty are highly important. As data becomes democratized, certain aspects of culture and history that shouldn’t necessarily be ubiquitously visible are becoming almost entirely legible and transparent to a global audience. Meanwhile, the ownership of data from local African contexts becomes centralized in data servers or private museum archives, which we are never given access to.

If we outsource the creative challenge of worldbuilding to AI, we rely increasingly on biased or limited data sets drawn from an online world that is over-represented by the West. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

As you mentioned, there is also the issue of bias. In architecture, we have this interesting, toxic relationship to labor. The promise of new generative AI tools such as Midjourney is that tedious tasks will be automated, freeing us to focus on a higher purpose that we have never actually defined as a collective human thing. If we outsource the creative challenge of worldbuilding to AI, we rely increasingly on biased or limited data sets drawn from an online world that is over-represented by the West. As a result, we are already cultivating a single, incomplete visual language that is driving the future. It is crucial to intervene in this on the ground floor before this dangerous loop snowballs. We need to ask instead how we can propel our existing ideals forward in alliance with these AI tools, rather than deploying them as servants of labor.

To conclude, how do you see your future as a designer unfolding? You sit at this intersection of technology and narrative, both of which shift incredibly fast in sometimes unpredictable ways.

I can see storytelling and radical imagination remaining central to my process, alongside the question of how they both shape and are shaped by space. I hope to always remain dedicated specifically to the African continent, our lost heritage, and our futures. Remaining in dialogue with emerging software also makes my practice pliable to mutation and evolution in ways that even I cannot predict. This digital realm is not only a medium for me but a continuum where these spaces and bodies of knowledge that I’m interested in can extend their lives.

For me, the digital realm is a generative space for exploring without absolutes. — Miriam Hillawi Abraham

I hope to remain a mediator between these intangible traditions and the solid architectures and infrastructures that we all see and experience. For me, the digital realm is a generative space for exploring without absolutes.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.