Whether through her art, writings, or lectures, Morehshin Allahyari's work evokes a range of emotions among its audience. There is wonder and intrigue at her reinterpretation of centuries-old Middle Eastern stories, images, and artifacts. There is introspection on our preconceived views on concepts from open-source data to digital archiving. Finally, there is a blend of frustration and motivation to act as Allahyari takes us on a journey through the exploitative history of colonial power relations between the West and the Middle East.

Using 3D simulation, video, sculpture, and digital fabrication, Allahyari warns us of a modern landscape in which power dynamics straddle both digital and physical worlds, articulating her theory of Digital Colonialism as a "framework for critically examining the tendency for information technologies to be deployed in ways that reproduce colonial power relations." In an age of artificial intelligence, the messages and critiques found within Allahyari's work take on a heightened sense of urgency.

In July 2023, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Allahyari about her life, work, and reflections on the relationship between technology, architecture, and power relations. The discussion, edited slightly for clarity, is published below.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

Niall Patrick Walsh: Could we begin with an overview of you and your work?

Morehshin Allahyari: I am an artist who works at the intersection of technology and activism. My work is often research-based, and over the past ten years, topics central to my projects have included archiving, ficto-feminist thinking, speculation, re-figuring, and Digital Colonialism. I come from a background that is actually not art-oriented but was instead grounded in social science and media studies. These were my original areas of study for my undergraduate at Tehran University in Iran before I came to the United States to study digital media art. Over time, these worlds have naturally come together in my practice, and I always seek to give each of them their own weight and importance.

As you mentioned, this journey through social science and media has included a specific focus on technology, whether it be 3D simulations, digital fabrications, etc. Where did that interest come from? Was it always present in your life, or did it emerge as your career unfolded?

My teenage years were formative for both my artistic and technological interests. I became obsessed with creative writing, and even took extra classes in school just to write stories. Meanwhile, my father bought me my first computer when I was a teenager, which was a huge revelation for me. This was in the late 1990s and early 2000s when dial-up internet was still the norm in Iran, but I nonetheless saw the internet as this entrance to an outside, digital world. I naturally became obsessed with digital technologies and the possibilities they offered. From my room in Tehran, I could venture out into a whole new world that would otherwise have been inaccessible.

I am thinking about technological relationships as well as the power relationships in which technology plays a role. — Morehshin Allahyari

Later, in my undergraduate, we had a class called Virtual Studies, which was the only class in my degree relevant to digital media. I was incredibly inspired by the subject and was determined even more to bring together the worlds of technology and art, including creative writing, art creation, art research, and projects that manifested them. Thinking back, it all came together very organically, and my work today is very much a representation of this background.

Today, you are based in New York and sit at this intersection of technology, art, and activism. There are so many topics and themes you address at this intersection, including power relations, Digital Colonialism, myths, multimedia, etc. Before we explore these in detail, is it possible to capture the totality of your work in a singular mission or framework?

The term ‘re-figuring’ or ‘re-figuration’ is one that I use to capture my work across myth-making, historical preservation, archival work, and their relationship to technology. I engage often with the idea of ‘re-figuring’ the past, whether that is reconstructing something that was destroyed or shedding light on histories and stories that have been misrepresented, underrepresented, or forgotten. Through this re-figuring of the past, I can start to re-figure possible futures or even possible present moments, particularly in the context of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, which is where much of my interests and focus sits. Throughout all of this, I am thinking about technological relationships as well as the power relationships in which technology plays a role.

I engage often with the idea of ‘re-figuring’ the past, whether that is reconstructing something that was destroyed or shedding light on histories and stories that have been misrepresented, underrepresented, or forgotten. — Morehshin Allahyari

A good example of this is my Material Speculation: ISIS series, which I worked on from 2015 to 2017. I reconstructed a series of sculptures and artifacts destroyed by ISIS at Iraq’s Mosul Museum in 2015. The process of 3D modeling and 3D printing these artifacts was incredibly complicated. There was a lack of information but also incoherency within the archival records of these artifacts, such as names not matching each other. Nobody knew about these artifacts, really. There was so little information available about them for several reasons. Iraq had been in a state of war for decades, the museum was understaffed and underfunded, and much of the research on these artifacts had been undertaken by scholars outside the Middle East whose information was perhaps lost in translation from Arabic to English.

I undertook several months of research to understand these layers, including tracing histories that were destroyed and separating originals from copies or replicas. When it came to creating 3D printed artifacts for my series, I embedded a USB and a memory card in the body of the sculptures, so that the sculptures themselves would become time capsules. Data within the memory cards includes PDF files, my email correspondence with scholars and historians, books, images, and even 3D printing files, which would allow someone with possession of the memory card, presumably from destroying the sculpture holding it, to reprint them again. The project was, therefore, both a political and a practical gesture. You cannot replace what is lost, but for me, it was about trying to protect against the removal of history itself.

Tech companies from the Global North may collect this data in the MENA region with the justification that “we are coming to save these artifacts for you,” but really, where does this data go? — Morehshin Allahyari

The project also came at an important moment at the intersection of technology, politics, and power relations. In 2015, there was growing hype around the possibilities of 3D printing and 3D scanning. I observed US and European tech companies traveling to the Middle East, and particularly Syria, to 3D scan artifacts amidst ongoing crises and domestic wars such as the Syrian Civil War and ISIS acts of destruction across the region. But, of course, the Middle East has a whole other history of US military involvement. Given my own childhood in the region, the fact that Western imperialism and the War on Terror had contributed to the destruction of artifacts and the historic fabric was never in doubt. It was equally clear that this violence was unnoticed and underreported when compared to the destruction caused by ISIS.

While watching Western tech companies scanning artifacts and historical sites across the MENA region, I began to ask: What is happening to this data? What happens to the 3D models or 3D scan data they bring back to Europe and the US? Who owns it? What are the copyright questions? This is where my entire Digital Colonialism project emerged from.

When we think about the historical colonialism of the West towards countries in the Global South, we all understand the ‘physical’ colonialism. You can go to the British Museum or the Met, see the objects on display, and be aware that many arrived from the Middle East by theft or being sold on a black market. In fact, we’ve recently seen the early steps of museums attempting to address the dark histories of physical colonialism by either returning objects to their place of origin or being open to discussions about it.

But when it comes to Digital Colonialism, and the digital ownership of data, the space is still very grey. There are many questions to be asked, and problems around unethical practices to be addressed. I therefore began asking questions about data ownership; questions about the power dynamics in access to technology. Tech companies from the Global North may collect this data in the MENA region with the justification that “we are coming to save these artifacts for you,” but really, where does this data go? Who has access to it? These are the central questions in my work on Digital Colonialism.

As part of your work on Digital Colonialism, you address the concept of ‘open source.’ In today’s culture, open source is almost always viewed in a positive light, which is understandable. For most of my life, my view was that information being freely available and accessible to all was a positive thing, particularly when it comes to history and culture.

The more I read and listened to your arguments about open source in the context of Digital Colonialism, however, the more nuanced this discussion becomes. You make a compelling case that, in this context, there is actually a benefit to layering access to information rather than making all data open source. Can you unpack that case more?

The Material Speculation: ISIS project is actually quite relevant here, too. After months of research and having created the sculptures, I found myself asking: What do I do with all of these 3D printable files? I began by releasing one file into the public domain, which was a sculpture of King Uthal, meaning anybody in the world could print it. I held onto the other 14 files because I wanted to see what would happen to this one file first. As I expected, the only people who accessed, shared, and had the capability to 3D print the file in 2017 were in the Global North.

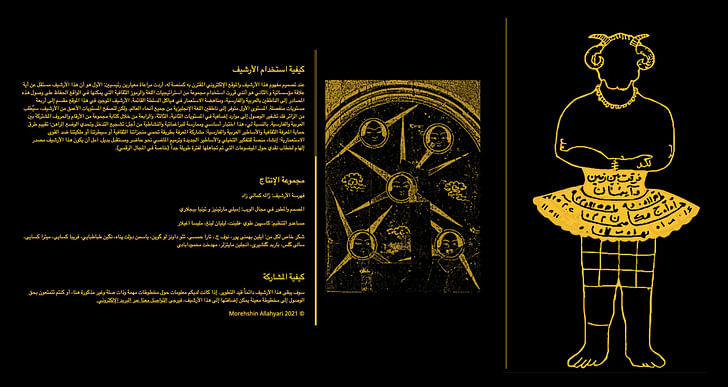

I had a similar experience with my project, She Who Sees The Unknown, in which I devoted three years of my life to digitally scanning manuscripts and gathering data about mythical monstrous female/queer figures of Middle Eastern origin. Through that process of material gathering, I encountered heavy gatekeeping by Western institutions that would not give me access to certain manuscripts or images.

When it was time to release the material myself, I came to ask: Who is this data for? Who do I want to give this data to? What does it mean to share knowledge while also protecting knowledge, especially in this world of colonial power dynamics between the Global North and Global South? Digital Colonialism isn’t just about architectural cultural heritage. It can be applied to many other forms of understanding our relationship to data and knowledge sharing.

What does it mean to share knowledge while also protecting knowledge, especially in this world of colonial power dynamics between the Global North and Global South? — Morehshin Allahyari

As a result, when I released the archive, I built a platform where if you understood Arabic of Farsi, you could get through the second, third, and fourth layers of the archive. As you move through this archive of PDF files, images, scans, etc, the information becomes more and more unique. If you only know English, you can have access to the first layer of the archive, which is still a substantial amount of material. But for me, it was a question of ‘who is this information for?’ It mattered to me that I should give this information back into the hands of people who hold a deep connection to it. In the past, I’ve seen this kind of information being used by people who don’t have a cultural relationship to it, and instead use it for a monster in a video game. You can tell that those creators have no cultural or spiritual connection to these beings.

As you mentioned, people inherently think open-source information and knowledge is always good. In a world that was actually equal, this would make a lot more sense. But in a world that is interlaced with issues around access to knowledge, cultural reappropriation, and cultural colonialism, I see a value in experimenting with these layered platforms as a way of asking questions and encouraging discussion.

We’ve talked about Digital Colonialism in the context of 3D printing, artifacts, and literature, and I think it would be interesting to view artificial intelligence through the same lens. You previously gave a lecture in which you presented three factors of Digital Colonialism: copyright ownership, monopoly on information, and monetary benefit. These three factors are also central issues and concerns in the context of the rise of generative AI, whether that is the concentration of AI tech companies in Silicon Valley, biases, the farming of public data, and copyright infringements, to name a few. What are your thoughts on how Digital Colonialism could manifest in AI?

It is highly relevant. I recently used AI in my project Moon-faced, which explored queer history in Iran within Qajar dynasty portrait paintings. In these portraits, it is unclear whether the subject is a man or a woman, and the notions of beauty are very gender-fluid. The time period we are talking about here is from the start of the 19th century through to the beginning of the 20th century. This history was affected by the Westernization of Iran through the years, and by the end of this period, Iranian painters were no longer painting gender-fluid portraits. Before the Western influence, notions of beauty for women in the paintings included having mustaches and uni-brows, while men might have a thin waist and feminine features. By the end of the 19th century, with the modernization of Iran and the introduction of camera technology, the portraits became much more gendered.

In effect, I was trying to overcome the model’s lack of knowledge about this entire history. — Morehshin Allahyari

For Moon-faced, I was interested in using a generative AI image model to create portraits inspired by the Qajar dynasty before this change occurred. Of course, the model I was using was unable to go back 250 years and pull material from this history, whether I used words in English or Farsi. I found myself having to ‘trick’ the model, even by using prompts such as: ‘a lesbian couple holding hands in the style of a Qajar painting’ while feeding it images from my archive. It would then generate images that included an LGBTQ+ rainbow, which in turn led me to experiment with phrases such as ‘gender-fluid’ to avoid the model’s embedded biases in how words translate to images. In effect, I was trying to overcome the model’s lack of knowledge about this entire history.

Separately, I’ve been experimenting with Midjourney for quite some time. I asked the model to imagine a woman with a hijab standing next to a woman without a hijab on the streets of Tehran. It couldn’t do it, and would only offer me women wearing hijabs. I found this bizarre. Women in Iran have been fighting for their right of choice or agency about wearing the hijab for centuries. There have been many feminist movements, protests, conversations, and, more recently, the killing of Mahsa Amini in September 2022, which spurred even more conversation around freedoms and agency for women. Despite all of this, the data used to train this AI model resulted in the idea that all women in Iran wear the hijab.

It is as if every bias in the world, whether politics, injustice, or inequality, is always reflected in technological tools. Artificial intelligence is no exception. — Morehshin Allahyari

I recently gave a talk at the New Museum where I spoke about how, in this case, the shallow technologists and the fascist dictators have actually become one. They exist in a common world of patriarchs who decided through data and algorithms that ‘women in the Middle East equals oppression,’ and that’s all. If I ask the model to imagine the future of women in Iran in the way I want it to be, it won't do it. If I ask it to imagine a future in the United States, it has no problem. It is as if every bias in the world, whether politics, injustice, or inequality, is always reflected in technological tools. Artificial intelligence is no exception.

As artists, critical thinkers, and educators working with these tools, it is vital that we raise such concerns. What kind of world-building are we facilitating? How can we actually change or affect it? The world of Silicon Valley feels so separate from the world of critical thinking. My wish is for these two spaces to come together to allow conversations to occur around how we can build, fix, and reconfigure technologies, and how we can develop a better understanding of access, power dynamics, Digital Colonialism, and more.

I recently spoke with Felecia Davis on this issue of bias both within the teams developing AI tools and and within the data itself being used to train models. One of the most bizarre aspects of AI bias to me is how obvious it is. We aren’t just talking about hidden, undetectable biases that subtly propagate inequalities or stereotypes; we are talking about incredibly fundamental cases such as AI facial recognition being less accurate for Black users, or AI image tools not being able to comprehend the idea of Iranian women without a hijab.

It is concerning how little seems to have been learned from the history of technology breeding inequality, and how even now, AI tools are being released and adopted at a breathtaking pace despite so many outstanding and unresolved dangers.

Sometimes my mind is blown away by the lack of questioning and critical thinking in this sector. I am often in tech spaces and find myself asking: ‘What world are you all living in?’ My world of educators and critical thinkers is probably equally as estranged from them, and that is the problem. When I leave my bubble of educators and universities and visit a Metaverse conference, the people there are operating on a different level in a different world.

The question remains: Why does technology continue to move forward with these worlds so separated, despite the resulting harm in how these technologies are both developed and used? Why is there so little concern around technological power imbalances? I don’t know what else I can do to make these developers feel uncomfortable, partly because I don’t have access to their spaces. Imagine if more tech companies hosted workshops from BIPOC artists, designers, and activists to talk about these issues. Imagine if such companies had a mini critical thinking school in their company.

In fact, Molly Wright Steenson recently made the point to me that tech companies are moving in the opposite direction, with Facebook, Google, and Microsoft all dissolving various ethics teams within their companies. One avenue of hope I have seen through various conversations on AI and design is the capacity for creativity to unlock a mode of critical thinking that more academic or scientific methods do not. Behnaz Farahi and Liam Young are two recent conversations that come to mind, in addition to your own work that we’ve explored today.

It’s a way of being. At the moment, I am working on a documentary film that looks at the history of technological and scientific tools in the Middle East from the Islamic Golden Era, which was itself an anchor point for the development of scientific thought in the West. One of the more intriguing aspects of this story is how many of the scientists at that time were also interested in spiritual thinking, and the idea of something larger than themselves in the universe.

I’m not personally religious, but I do operate in the world by building connections with the universe or the energies in the world around me. — Morehshin Allahyari

One example is Ibn al-Haytham, who invented the camera obscura and many other tools in the field of optics; he was also a spiritual person. I’m not personally religious, but I do operate in the world by building connections with the universe or the energies in the world around me. It’s not a lifestyle, it is a philosophy.

I believe we have much to learn from these histories of previous scientists and inventors and the ways they lived life. There is something simple yet beautiful there.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.