Black America’s need over the next several generations is for an “apostate architect” wing [to complement the budding generalist design and theory architect wings]. The apostate wing must be capable of and motivated to play a vital role in the business of wealth creation-centered community production of affordable housing and related community facilities. Given the reality that [highly motivated] African Americans who could be interested in careers in architecture are not willing to take the profession’s de rigueur “vows of [personal] poverty,” an alternative re-purposed medical doctor modeled curriculum would also solve the architect’s unacceptably low compensation issue.

Melvin L. Mitchell continues with Part 2 of Black MD’s, Lawyers…and Architects. Click here to read Part 1.

During the early 1980s, I came across several thoughtful articles in Architectural Record magazine that argued for an academic-profession curriculum reform based on the medical doctor curriculum. The argument never gained traction but has continued to resonant with me. The medical model made the most sense for the HBCU-based architecture programs, several that I was deeply immersed in at that time.

By 1999 I was at the midpoint of my term heading the Morgan Institute of Architecture & Planning in Baltimore. I began writing my first book, The Crisis of the African American Architect: Conflicting Cultures of Architecture and (Black) Power (2002), and targeted primarily at what I believed was a crisis of cultural disconnection between Black architects and Black America. I was also alarmed at the appallingly low levels of Black student interest — and eventually success — in the pursuit of careers in architecture. In that book was a chapter titled “Beaux Arts-Bauhaus Myths, Rituals, and Fetishes.” During that time a 1996 published report, Building Community: A New Future For Architecture Education and Practice by Ernest Boyer and Lee Mitgang, was making the rounds. This was a serious call for a deep reform that I expected could be the architecture education and practice reform equivalent to the 1910 Flexnor Report that revolutionized the modern medical education profession and led to the closing of half of the nation’s then-existing medical schools.

My central concern, then as now, was the seven HBCU-based, accredited architecture programs at Howard, Morgan, the University of the District of Columbia, Hampton, Prairie View, Tuskegee, and Florida A&M. Those schools had collectively played a historic, base role in the education of Black architects. In the mid-1970s those schools were laying claim to having graduated nearly half of the nation’s licensed Black architects. According to the most recent National Architectural Accreditation Board (NAAB) statistics, those seven programs continue to this day to enroll nearly 35% of all Black students matriculating in the nation’s 180 accredited architecture programs.

In my book, I advocated that each of the seven HBCU-based programs double their enrollment sizes. I then posed the question, “doubled to do what? To function how? And on what missions that might differ fundamentally from the other TWI programs?” I argued that the HBCU architecture schools — in stark contrast to the four HBCU-based medical schools (Howard, Meharry, Drew, and Morehouse) — have missions that are not aligned with the national “Black Agenda,” Black America’s consensus call for the elimination of disparities in White-Black health, adequate housing, good-paying jobs, average family wealth, and home and business ownership. Rather, and perhaps unwittingly, the HBCU-based architecture school’s shared core mission — despite what was being stated — appeared to me to actually be to increase employment opportunities for Black architecture graduates in a world of increasingly non-Black owned professional practices. I saw no prospects of those schools’ changing those missions.

Today, four decades after my initial encounter with thinking about the notion of a medical doctor model for architecture education and practice, I came across a book, The Future of Modular Architecture, written by architect/educator David Wallance who put 15 years of research and thinking into this timely and forward-looking effort. I was already on board with many of Wallance’s ideas about the evolving role of architects in the Information Age Revolution. The architecture that Wallance focused on was what he called the “utilitarian specialties.” He mainly meant affordable, sustainably housing while fully acknowledging the continuing need for the artist-oriented design of symbolic non-residential buildings by the orthodox architect. This particular Wallance paragraph stood out for me.

The explosion of new fields of knowledge, and the scale of complexity of building projects has changed the practice of architecture the way it has changed, for example, the practice of medicine with its proliferation of specialties. If the thesis put forward in this book regarding intermodal architecture proves correct, architects must reorganize.

I took “reorganize” to mean architects’ “repositioning” themselves within the rapidly transforming ecosystem that actually constructs the built environment. My own thinking is that this new position might more resemble how the medical doctor is positioned in the nation’s health care ecosystem. Despite that ecosystem’s obvious flaws of non-medical doctor corporate bloat, it is still the envy of the world. In that health care ecosystem, today’s (Black) licensed Doctor of Medicine graduate typically receives a salary in the $65-80,000 per year range over a three or four-year intern/residency period with expectations of jumping quickly to $200,000 and well beyond that shortly afterward. With rare exceptions, the architecture profession as currently structured cannot accommodate either of those levels of compensation. However, there are growing examples of public-private funded entities that can provide such compensation for appropriately educated and trained Master of Architecture graduates.

In today’s world, everything except sentient matter can or has been digitized (including money) and is able to traverse the globe at the speed of light. We have the means and tools to design and build structures (and cities) that bear very little relation to the means and tools we used 50 years ago. Contrary to that reality, most architecture schools continue teaching and inculcating thinking processes that are grounded in the 1970s pre-Information Age era. Structuring an architecture curriculum based on current scientific and technological capacities goes against deeply entrenched intuitive grains embedded in the culture of the academies and most small to medium-sized firms in professional practice.

In stepping back a moment, we must note here that in this early post-George Floyd era, 40 million African Americans (12.5% of the U.S. population) now live in a time that requires deeper, more honest, and fact-based reflection on where we have been since the 1877 collapse of Reconstruction, and the bittersweet road that brought us to today. Equally important is the issue of where we are trying to go over the next two decades. In Black America — now “splintered into four distinct parts” according to NYT columnist Eugene Robinson in his 2010 book Disintegration — the time is well past to put aside the multitude of manifestos, recriminations, internal finger-pointing, and circular firing squads on whether Booker T. Washington or W.E.B. DuBois, Malcolm or Martin, etc. We have arrived at an early 21st-century reality of unlimited possibilities co-existing alongside frightening prospects of imminent civilizational collapse.

Today’s total of 120,000 licensed American architects includes just under 2% (2,500) who are Black. Possibly an additional 2,000 more Black architecture degree holders are functioning in professional capacities. (In comparison, there are 50,000 Black licensed medical doctors, comprising 5% of the nation’s just under one million licensed physicians) Black architects today are increasingly insisting on becoming seriously-taken participants in the great debates across Black America about which way forward. Any objective conversation about the architecture and medicine professions requires a comparison of the structure of formal education for those professions.

My own experiences, observation, and research have led me to believe that Black aspiring architects who pursue a med school-modeled path of a three to four year Masters in Architecture degree preceded by a four-year (preferably not architecture) undergraduate degree have a substantially higher chance of graduating, going on to achieving licensure, being able to demand higher than average annual salaries, and more likely to form entrepreneurial practice endeavors that entail personal financial risk-taking.

To logically align curriculum with the Black Agenda while increasing success rates of graduation, licensure and the building of effective professional practices require the creation of a new architecture education model. The goal and mission of that model is to produce that medical doctor-equivalent architect who will be, upon graduation and licensure, the job and wealth-producing catalyst so badly needed by Black America. The financial viability of such new housing production-oriented practice entities rests firmly on the basis of need and the inevitability of emerging progressive socio-economic reforms. The reality is that everything once thought to be pipe-dreams, including the Green New Deal is now in sight of full realization between now and over the coming decade (the smartest politicians will rebrand the GND as “saving capitalism’).

Accordingly, after two decades of proselytizing for a deep, structural change in the mission of the HBCU-based architecture programs I am now part of a small group of mostly younger, now and next-generation practitioners who have founded a new alternative academic-professional practice clinic.

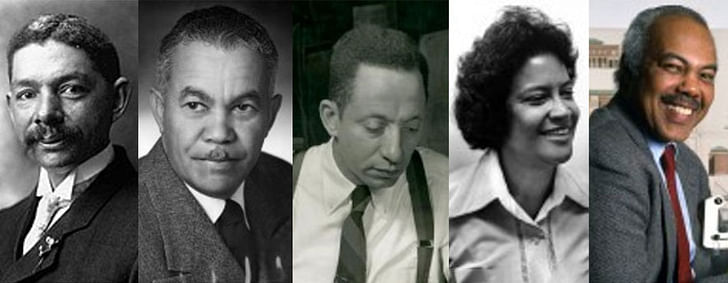

The National Institute of Architecture & Housing (TNIAH) founders were inspired by the interconnecting lives and accomplishments of Robert Taylor, Paul Williams, Hilyard Robinson, Norma Merrick Sklarek, and Max Bond, who they regard as arguably the most impactful and influential African American architects of the 20th century. These five people were the producers of a vast range, number, and scope of built-works, many of great importance in African American history, culture, and economic advancement. Taylor, Robinson, and Bond also served in pivotal leadership roles as educators in historically important American architecture schools that include Bond’s role as an instructor in the architecture school at the Kumasi Institute of Science and Technology in Ghana.

The TNIAH mission — meant in the spirit of a 21st-century re-incarnation of the five entrepreneur-practitioners — is to prepare 21st-century generations of architects who focus on the use of AI-based technology to conceptualize, manufacture, and deliver affordable, sustainable urban housing as a communal wealth creation strategy.

As a new education enterprise, TNIAH will stand in contrast to, for instance, the Africa Futures Institute (AFI), the much-needed, new architecture school in Accra, Ghana founded by Leslie Lokko and David Adjaye. AFI is a fitting Sub-Saharan Africa counterpart to the several high-profile British and American architecture schools that spawned much of the AFI leadership. This is particularly so in the case of the globally renown Architectural Associationalma mater of Lokko. There are other promising new Black-oriented school entities here in the U.S., most notably, Dark Matter University, the Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) design movements, and Black Reconstruction Collective. All are essential and promising movements and forums for high-level intellectual discourse and theory. All of those entities will no doubt be concerned with affordable, sustainable housing but will prioritize the symbolic non-residential structures, cultural spaces, and places in juxtaposition to the TNIAH role as housing production catalyst. The TNIAH education-practice reform model will co-exist synergistically with all of those entities.

The TNIAH vision is the catalyzing of a national housing industry devoted to increased economic and business development, and ownership in African American communities. The key strategy is the gaining of command of all phases of the integrated design, production, and delivery of one million affordable, sustainable homes and housing units — trillions of dollars — while maximizing the amount of deployable money and dollar flow through the entire Black ecosystem of entities including labor required to produce a housing unit. TNIAH students, interns, faculty, partners, and affiliated business (some to be abetted by TNIAH in start-up mode or later stage support) will all be included in a nexus of graduate degree-granting community design centers and modular housing production clinics.

The story of the lives and times of the TNIAH Five began with Robert Taylor’s 1893 arrival on Tuskegee’s campus in Alabama. His charge, as I have argued, was to actualize Booker T. Washington’s dream of building a “Black City” to counter the “White City” (The 1893 Chicago World’s Fair) 600 miles north of Tuskegee) and its racist resistance to positive Black participation in the building of a “White City.”

In 1907, Paul Williams, a 13-year-old Los Angeles paperboy, read the story and saw the pictures of William Sidney Pittman and his design for The Negro Building in Norfolk, VA. Pittman was one of Taylor’s Tuskegee architect/faculty members. Young Williams became fortified in his dreams about becoming an architect, a feat he accomplished upon becoming California’s first Black licensed architect in 1921, first Black member of the American Institute of Architects in 1924, and open his own office, Paul R. Williams & Associates in 1928 in downtown L.A.

By 1932, a decade before Taylor’s death, enterprising young Los Angeles practitioner Williams was entering into a bi-coastal partnership with Washington, DC’s Hilyard Robinson, a young Howard University professor/architect. Their collaboration resulted in Langston Terrace Dwellings, praised by Lewis Mumford as the equal to the finest social housing being produced in Europe. Their partnership designed numerous buildings on Howard’s campus including the E&A Building, opened in 1954 and serving as the training site of thousands of Black engineers and architects.

Norma Merrick, born in 1926 and raised in Harlem and Brooklyn, came by her awareness of the Williams-Robinson exploits (and possibly Taylor’s) through her father, Walter Ernest Merrick (1896-1965). Mr. Merrick received his training as a medical doctor at Howard in the early 1930 era of Mordecai Johnson, who was Howard’s first Black president and presided over the major physical expansion of the modern campus. Johnson recruited Black architect Charles Cassell who chaired the Howard architecture department before handing the position over to his own recruit, young Hilyard Robinson. Dr. Merrick is reported to have taught Norma carpentry skills and encouraged her to pursue a career in architecture.

Norma Merrick graduated from Columbia University’s architecture school in 1950 and was a licensed architect by 1954 at age 28. Merrick pioneered the trail for Black women in leadership roles in the corporate world of large-scale practices. She encountered the litany of racial and gender discrimination on her rise through large architectural firms in New York and Los Angeles. Dubbed as the “Rosa Parks of architecture,” in 1967 Merrick married Los Angeles architect Rolf Sklarek. She led the design, technical drawings production, and construction administration of large, iconic projects before founding her own firm, Siegel Sklarek Diamond. Merrick was a role model and mentor to many of today’s 500 licensed Black women architects.

Much of Merrick’s professional career was spent as the architect-principal charged with turning the design sketches of world-famous design architects into completed realities. With the exception of The Pacific Design Center and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, Sklarek is rarely given due credit as the architect.

And then there is Max Bond, born in 1935 in Kentucky just 9 years after Sklarek’s birth. The precocious Bond was raised on Taylor’s Tuskegee campus and earned his Harvard BA and M.Arch degrees by age 23. In 1957, a year before his graduation, he drove across the country to Los Angeles to spend that summer working in Williams’ office as a designer. Bond is purported to have learned just before his death in 2009 that the Freelon Adjaye Bond team he had earlier assembled was going to be selected to design the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

TNIAH has come into being through the emulation of the radical course of actions taken a half-century ago by the late great practitioner-educator Ray Kappe in his 1972 founding of the free-standing independent Southern California Institute of Architecture, aka SCI-Arc. Kappe and a small group of instructors and students walked away from an entrenched Cal Poly-Pomona Department of Architecture in their search for more experimental approaches to the art of designing buildings than those found at the rest of California’s architecture schools. While TNIAH has no interest in the Kappe-SCI-Arc “experimental design” agenda, for obvious reasons there is also a need to emulate the SCI-Arc pursuit and achieving in the shortest time frame, validation by the authorized academic regimes. A number of the key pillars in the TNIAH reform model — most notably the NCARB-initiated Integrated Path to Accelerated Licensure, aka IPAL, and the elimination of a mandatory requirement for a lengthy post-graduation time in a traditional practice office prior to eligibility for sitting for the licensure exams — are already in operation at a select number of the nation’s 180 programs.

The larger vision is that the impact of all of the entities should result in the eventual transformation of the current seven HBCU programs as well as the creation of possibly a dozen more new programs on HBCU campuses that precisely aligned physically and programmatically with urban African America’s socio-economic and cultural interest and need for a national housing industry devoted to pumping trillions of dollars through blocks, communities, and several new cities.

Today, TNIAH is in the process of convincing philanthropists and venture capitalists that an appropriately trained and socialized licensed apostate architect’s value and contributions to the elimination of key glaring U.S. White-Black socio-economic disparities can begin to rival that of the of Black medical doctors in fact as well as in the minds of Black America… to be continued.

Melvin L. Mitchell, FAIA, NCARB, NOMA

Melvin L. Mitchell has been in practice in Washington, DC for 45 years, a past president, DC Board of Architecture, former director, the Institute (now school) of Architecture & Planning at Morgan State, and former full-time faculty member at Howard and University of the District of Columbia ...

1 Comment

Great article!!!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.