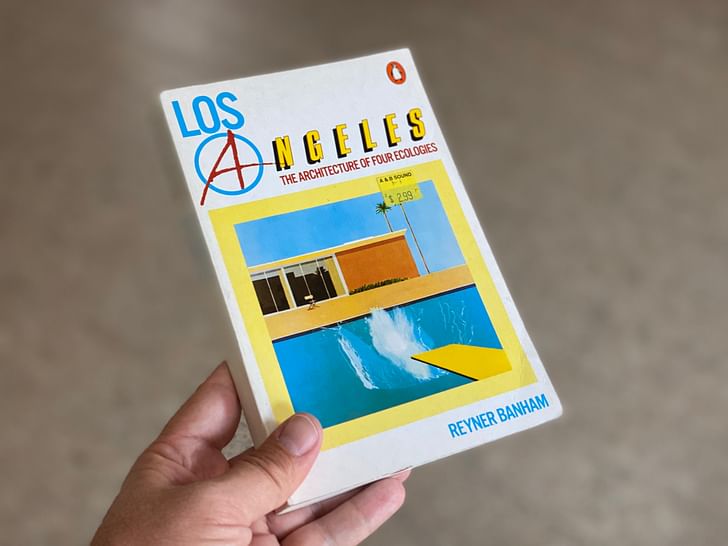

If you have an interest in Los Angeles, you also have a copy of Reyner Banham's Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies. My own is a mid-1980s Pelican paperback, which I chose because it had the dumbest cover of all the editions. Though it shares with previous printings the image of David Hockney's A Bigger Splash, an unimpeachable representation of a certain midcentury vision of the city's hauntingly good life, its title replaces their elegant Helvetica with letterforms better suited to a post-apocalyptic action movie gone straight to video. "Angeles" is spelled out in forward-slanting, shadow-casting, bright yellow capitals but for the red initial "A," rendered as if hastily spray-painted and set inside a circle to form the 1970s anarchy symbol. Right, Los Angeles — that's the zone of semi-controlled urban chaos obedient to no conventional rules or order, architectural or otherwise, isn't it?

How did Banham, who died in 1988, regard this dubious piece of graphic design? Each of his many enthusiasts and exegetes active today would speculate differently, according to which facet of his oeuvre they know best. Having first trained as an aeronautical engineer before undertaking an architectural-history education, Banham first became widely known in his native England through magazine columns in the 1950s and 60s. There he practiced criticism: sometimes of architecture, to be sure, but more often of practically everything else then found at the intersection of culture and technology. In the study Reyner Banham: Historian of the Immediate Future, Nigel Whiteley sums up the range of these public-facing writings: "Car styling; the design of radios and cameras; graphics on magazines, cigarette packs and potato chip bags; the decoration of restaurants, surfboards and ice cream vans; cult films and TV programs — all were grist for his mill."

Half a century of technological developments and cultural-studies lectures on, these subjects will strike most of us as obviously (or at least potentially) worthy of serious consideration. That wasn't the case for Banham's generation, whose members came of age with a painfully keen awareness of the line dividing "high" from "low." Born in 1922 to a not particularly well-off family in the provincial town of Norwich, Banham the self-described "scholarship boy" bristled all his life at received notions of absolute cultural hierarchy. He criticized the denigration of popular taste as "old, standardized and unquestioned, public-school-pink." From these prevailing attitudes, as well as England's lingering wartime austerities, an escape route appeared in the form of American commercial culture, its artifacts having been imported in unprecedented abundance in the late 1940s and early 50s as Banham was working toward his PhD at the University of London's Courtauld Institute of Art.

While still a student, Banham came together with a few like-minded countrymen to form the so-called "Independent Group," who from 1952 to 1955 mounted their own forward-thinking lecture series on new developments in art, culture, and society at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. Other participants included the sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi, the artist Richard Hamilton, and the architects Alison and Peter Smithson. "If there was a common starting point for the IG, it was a fascination, framed as un-British if not anti-British, with American culture," writes Louis Menand in his new study The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War. "That fascination was not ambivalent." And Banham, it seems, laid fair claim to being the not just the most argent technophile of the group, but also — not unrelatedly, given the United States' unmatchable economic might at the time — its most ardent America-phile.

Of course, he would gravitate to Los Angeles, a city familiar to him from all the "penny pictures" he saw growing up, and whose own technological and mass-cultural production in the mid-20th century made it an America within America. Yet he didn't visit the United States ("the realization of a longheld dream," said his wife Mary) until 1961, and only made it to Los Angeles four years thereafter. In a 1968 BBC broadcast, he confesses that he at first found the gigantic Southern Californian metropolis "totally incomprehensible." But subsequent trips convinced him that "the language of design, architecture, and urbanism in Los Angeles," as he writes in The Architecture of Four Ecologies, "is the language of movement." And so, "like earlier generations of English intellectuals who taught themselves Italian in order to read Dante in the original, I learned to drive in order to read Los Angeles in the original."

... like earlier generations of English intellectuals who taught themselves Italian in order to read Dante in the original, I learned to drive in order to read Los Angeles in the original" - Reyner Banham

Even more quotable, for my money, is Banham's observation that "Los Angeles does not get the attention it deserves — it gets attention, but it's like the attention that Sodom and Gomorrah have received, primarily a reflection of other peoples' bad consciences." This comes in the final chapter, where Banham justifies having given consideration as serious to Los Angeles as he had to all those tail-fins and snack packages in his magazine pieces. When he began, there many "were ready to cast doubt on the worth of such an enterprise"; half a century after The Architecture of Four Ecologies' publication, the book stands nearly alone in its class. With a new edition (missing both A Bigger Splash and the A-for-anarchy) issued in 2009, it remains a book often recommended — quite possibly the book most often recommended — to new Angelenos looking to understand the city and its built environment.

I certainly wasted no time in absorbing Banham's view of Los Angeles when first I lived there a decade ago. He provided the most coherent set of answers by far to the question about the city that obsessed me: "Why is it like this?" Many Angelenos have asked the same, of course, though often out of exasperation, even resentment; I asked out of an increasingly all-consuming fascination that did a great deal to motivate my move in the first place. But before one can address that question, one must define what it means to be "like this," a diagnosis no two observers of such an expansive, varied, and troubled city as Los Angeles will make in quite the same way. Whether one agrees or disagrees, the enthusiastic and erudite descriptions collected in The Architecture of Four Ecologies have come to form a background for the discussion.

Banham's Los Angeles is "instant architecture in an instant townscape," all of whose parts "are equal and equally accessible from all other parts at once." This accessibility owes to the region's freeway system, "one of the greater works of Man." It's also "the greatest City-on-the-Shore in the world," where, "one way and another, the beach is what life is all about." Due to Los Angeles' distinctive local climate and geography, "the difference between indoors and out was never as clearly defined," nor "as defensive as it had been in Europe, or was forced to be in other parts of the USA," making it a congenial setting for modern architecture. But such notable buildings contribute less to the city's "unique character" than does its "proliferation of advertising signs": "to deprive the city of them be like depriving San Gimignano of its towers or the City of London of its Wren steeples."

Already, many familiar with modern-day Los Angeles will have found points of disagreement. When I lived there it almost never occurred to me to go to the beach. Nor did I have many opportunities to drive on the freeways, having arrived with the vague intent to buy a car but soon realizing that I didn't really need one. Thus I was cut off from two of the four "ecologies" of Banham's title: "Surfurbia," the string of beach cities along the Pacific coast, and "Autopia," the network of freeways on which Angelenos "spend the two calmest and most rewarding hours of their daily lives." Scoffed at even in the 1970s, that line is in Whiteley's view Banham "overstating his case in order to counter the usual criticisms, often repeated without direct evidence, that the freeway system was a polluting, frustrating, extended traffic jam which brought out aggression and fueled alienation."

Just as Banham was a combination of historian, technology critic, and polemicist, The Architecture of Four Ecologies is at once a history, a work of technology criticism, and a polemic. So was his first book Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, an expansion of his PhD dissertation, which made his name in architectural-history circles when it was published in 1960. In it Banham assesses the automobile-symbolized "First Machine Age," the period of the 1910s and 20s that witnessed the proliferation of "power from the mains and the reduction of machines to human scale." He writes from the perspective of the television-symbolized postwar "Second Machine Age," in which "highly developed mass production methods have distributed electronic devices and synthetic chemicals broadcast over a large part of society." This ever more thorough integration of machine technology into human life was, to Banham's mind, a process of almost unambiguous improvement.

"It was Los Angeles," writes Whiteley, "that essentially consumerist, individualistic, creative playground of Homo Ludens that lacked a significant public realm, which encapsulated the values of the Second Machine Age most convincingly." This already much-disparaged city thus made an ideal ground upon which Banham could exercise his own increasingly contrarian techno-optimism, a not-uncommon position in his generation that had come under attack by the youth-oriented Rousseauian counterculture of the late 1960s. There he also identified, and celebrated, the secret ingredient of a characteristically American "innocence," one that "grows and flourishes as an assumed right in the Southern California sun, an ingenious and technically proficient cult of private and harmless gratifications that is symbolized by the surfer's secret smile of intense concentration and the immensely sophisticated and highly decorated plastic he needs to conduct his private communion with the sea."

This, safe to say, is not a passage that could have been written by Banham's mentor Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, historian of art and architecture as well as a thoroughgoing European modernist. Whiteley suspects that "Los Angeles would have appalled Pevsner and represented the demise of all that was good about the First Machine Age — collectivism, restraint and universality rudely replaced by individualism, Pop exuberance, and the freedom of choice: egalitarianism dreams overturned by the hedonist nightmares that money could buy." And if Banham could provoke with his approval of these characteristically postwar-American developments, he could also provoke with the individuality, exuberance, and freedom of his prose itself. "He is of course an extremely intelligent man and a first-class journalist," Pevsner once wrote of his former student. "But as soon as he is outside his scholarship, strictly speaking, he tends to write too well."

He is of course an extremely intelligent man and a first-class journalist, but as soon as he is outside his scholarship, strictly speaking, he tends to write too well

Of all the strengths that have guaranteed The Architecture of Four Ecologies a readership over the past fifty years, the clearest and most present are those of Banham's writing. Its uncommon assurance and verve come up almost without exception in assessments of the book's legacy, though almost never in the context of direct comparison with all the writing done about Los Angeles since. The dispiriting fact (and I make this claim having continued my obsessive reading on the city even now, living on the other side of the world) is that such works seldom even attempt to approach Banham's standard. Too many of them have been either academic or apologetic, running to tendentious theoretical "readings" of the city or drab enumerations of its sins and shortcomings. Few writers since Banham have found the right textual structure to reflect Los Angeles; fewer still have found the right tone.

The tone Banham found has been praised as "breezy," an adjective that belies the book's formidable scholarship. But it does get at the faintly comic visual flair that memorably manifests in, say, a consideration of the building type Banham labels the "Los Angeles dingbat." In back, each example of this "two story walk-up apartment-block" of wood and stucco displays "simple rectangular forms and flush smooth surfaces, skinny steel columns and simple boxed balconies, and extensive over-hangs to shelter four or five cars." But in front, this utilitarian structural similarity of one dingbat to another gives way to "a commercial pitch and a statement about the culture of individualism." Run through the "Los Angeles mincer," every style emerges on their façades from "from Tacoburger Aztec to Wavy-line Moderne, from Cod Cape Cod to un-supported Jaoul vaults, from Gourmet Mansardic to Polynesian Gabled and even — in extremity — Modern Architecture."

Even Angelenos lucky enough never to have lived in a dingbat know one when they see one. Banham counts it as a representative housing form of "The Plains of Id," to him the least distinctive and least appealing of Los Angeles' four ecologies, the central flatlands "where the crudest urban lusts and most fundamental aspirations are created, manipulated and, with luck, satisfied." They also happen to constitute most of the area of the city proper; hence the world's stereotypically grim image of Los Angeles, "gridded with endless streets, peppered endlessly with ticky-tacky houses clustered in indistinguishable neighborhoods, slashed across by endless freeways that have destroyed any community spirit that may once have existed." It's also where I lived in Los Angeles, as did nearly every other Angeleno I knew; not for us Banham's geographically outer but spiritually inner ecologies of Surfurbia or the (now even more prohibitively expensive) Foothills.

Banham's preference for Los Angeles' ocean shores and mountain slopes clearly owes in large part to the relative quality of their buildings. On the Foothills stand such notable residential projects as Frank Lloyd Wright's Ennis House, Richard Dorman's Seidenbaum House, and John Lautner's Chemosphere. Greater Surfurbia offers up the likes of Irving Gill's Horatio West Apartments, Rudolph Schindler's Lovell Health House, and even the Wayfarers Chapel by Wright's son Lloyd Wright. Some midcentury masters built across both of these ecologies: Craig Ellwood, for example, designed the equally well-regarded Smith House in Brentwood and Hunt House in Malibu, while Charles and Ray Eames sited their own celebrated Pacific Palisades home in the Foothills but also nearly on the coast (a fact underscored by Banham's photo of its Pacific Ocean view). It was the Eames House, in fact, that gave Banham his "first consciousness of any specific architecture in Los Angeles."

This first glimpse came through a magazine, and it is to a magazine that the Eames House owes its very existence: Arts & Architecture, which for two decades after the Second World War ran what publisher John Entenza called the Case Study House Program. "Eight nationally known architects, chosen not only for their obvious talents, but for their ability to evaluate realistically housing in terms of need, have been commissioned to take a plot of God’s green earth and create 'good' living conditions for eight American families," wrote Entenza in its announcement. Apart from the Eamses and Ellwood, participants included Richard Neutra, Pierre Koenig, Raphael Soriano, and others now synonymous with Southern California's midcentury modern domestic architecture. For a time, Banham writes, all this "really made it appear that Los Angeles was about to contribute to the world not merely odd works of architectural genius but a whole consistent style."

This "Style that Nearly..." gets its own chapter in The Architecture of Four Ecologies, though whether it nearly succeeded or nearly failed remains an open question. Its "houses as skinny steel frames infilled with glass" represent, "par excellence, an architecture of elegant omission that takes Mies van der Rohe's dictum about Wenige ist Mehr even further than the Master himself has ever done." Recent years' tour attendance and social-media posting confirm its enduring popularity among architecture enthusiasts. Yet as Banham sees it from his early-70s vantage, "the very puritanism and understatement that we admire in the Case Study style make it an unlikely starter in the cultural ambiance of Los Angeles — or rather, make it an unlikely finisher. The permissive atmosphere means that almost anything can be started; what one doubts is that there was enough flesh on these elegant bones to satisfy local tastes for long."

The goal of the Case Study House Program, as Entenza articulated it, was to produce an architectural form "capable of duplication," in no sense "an individual 'performance,'" and suitable for "the average American in search of a home in which he can afford to live." By this rubric, the Program must be written off as a failure. Nevertheless, images of the Case Study Houses themselves have proven lastingly influential enough to keep no few Angelenos dreaming of their own eventual splendid isolation in steel and glass — "embosked ever deeper," as Banham puts it, "in their tortuous roads and laurel privacies." In fact, this dream was becoming pure fantasy even in Banham's day, when he identified in the much humbler dingbat "the true symptom of Los Angeles' urban Id trying to cope with the unprecedented appearance of residential densities too high to be subsumed within the illusions of homestead living."

The story of Los Angeles in the fifty years since has largely been one of densification, and of tragi-comically wishful or incompetent responses to that densification. Banham records a near-total lack of awareness of the concept itself: before rolling out the "Los Angeles Goals Program" of the mid-1960s, "intended to involve the citizens in fundamental decisions about the future of the area," it was necessary first to explain "what town planning was, and exemplify rock-bottom concepts like High and Low Density in words and pictures little above primary school standards of sophistication." But even that effort stalled, defaulting to "the proposal that the city shall develop much as it has in the recent past — clusters of towers in a sea of single family dwellings." And so much of it has developed since, with those towers becoming somewhat more numerous, and in certain cases partially or wholly residential.

Banham's enthusiasm didn't blind him to the inevitable difficulties of a detached-house metropolis hitting its physical limits — nor to the solutions implicit in Los Angeles' unprecedented urban form. "Come the day when the smog doom finally descends, when the traffic grinds to a halt and the private car is banned from the street, quite a lot of craftily placed citizens will be able to switch over to being pedestrians and feel no pain." So he predicts over footage of the high-rise "linear downtown" Wilshire Boulevard was already becoming in "Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles,"a 1972 episode of the BBC television documentary series One Pair of Eyes. And though personally captivated by Los Angeles' freeway network, he writes in The Architecture of Four Ecologies that "it is inconceivable to Angelenos that it should not be replaced by an even better system nearer to the perfection they are always seeking."

That Los Angeles hasn't yet replaced its freeways would probably surprise Banham, but so would the city's current urban rail system. As often as he seems to have heard the idea brought up, he held out little hope for its full implementation: "When the socially necessary branch has been built, to Watts, and the profitable branch, along Wilshire, little more will be done and most Angelenos will be an average of fifteen miles from a rapid-transit station." Though still inadequate for an urban region of Los Angeles' size and stature, the Metro Rail network has far surpassed the extent Banham imagined. Granted, its expansion has been agonizingly slow going, the "profitable branch," for instance, having yet to reach the west side of the city. But the "socially necessary branch" has been in service for 30 years now, with a station dedicated to Banham's favorite work of Los Angeles architecture.

When the socially necessary branch has been built, to Watts, and the profitable branch, along Wilshire, little more will be done and most Angelenos will be an average of fifteen miles from a rapid-transit station

Hand-built between 1921 and 1954 by (and in the backyard of) a laborer untutored in art or architecture, Watts Towers present to Banham the most eloquent expression of Los Angeles' purpose: "The promise of this affluent, permissive, and free-swinging culture," as he puts it in one radio broadcast, "is that every man, in his own lifetime and to his own complete satisfaction, shall do exactly what he wants to." Cast of concrete embedded with pottery shards and other found objects, these rustically fantastical spires constitute "almost the only public architecture in the city — public in the sense that it deals in symbolic meanings the populace at large can read." This category also includes the city's oversized, light-up advertisements against which "orthodox city planners" fulminate, outnumbered though they are by "those who find something to admire in them, their flamboyance, and the constant novelty induced by their obsolescence and replacement."

Novelty, obsolescence, and replacement — the values of 1950s Detroit carmakers — are key to understanding Banham's view of Los Angeles, and of most everything else. "Concepts of art and aesthetics based on eternal values will probably continue to prove perishable," he wrote in a 1960 column on the Second Machine Age, "while Futurism, founded on change and '... the constant renewal of our environment,' looks to be the one constant and permanent line of inspiration in twentieth-century art." The Futurists' dedication to constant forward motion both metaphorical and literal proved, for Banham, more durable and true than any supposedly transcendent ideals offered up by more conventional systems of thought. But never did he parrot the Chamber of Commerce line about Los Angeles' being "the city of the future"; rather, he valued Los Angeles for giving concrete form to the modernity of the moment, entirely adapted to its distinctive environment.

"No city has ever been produced by such an extraordinary mixture of geography, climate, economics, demography, mechanics and culture," Banham writes in The Architecture of Four Ecologies, "nor is it likely that an even remotely similar mixture will ever occur again." This is not an argument for preserving the Los Angeles he knew. On the contrary, he admired the city's ability, willingness, and sheer available space to "swing the proverbial cat, flatten a few card-houses in the process, and clear the ground for improvements that the conventional type of metropolis can no longer contemplate." Had he lived longer, Banham the inveterate anti-conservationist would have come into conflict with the increasingly vocal set of Angelenos insistent on preserving the Los Angeles they knew — an impulse that extends even to the aforementioned advertising signs, elevating a Chevrolet dealership's neon Felix the Cat, for example, to the status of sacred object.

Los Angeles' most aggressive architectural conservation efforts strike me as comically apt illustrations of a disorder Banham warned against in an essay of the early 1960s: a loss of ability to "distinguish between the maintenance of the urban texture that supports the good life, and the mere embalming of ancient monuments." This may seem an unlikely position for an architectural historian to take, but Banham considered "preserve-at-all-costs" conservationists "anti-historians, trying to deny or destroy history, like someone trying to make the good times last by nailing up the hands of the clock. For history is about process; the objects the process creates are incidental." In the built environment or elsewhere, his own keen perceptions of these incidental objects, as well as what they reveal about the civilizations that produced them, continue to bring him new readers when even his novelty subjects have long since become period artifacts.

Banham considered 'preserve-at-all-costs' conservationists 'anti-historians, trying to deny or destroy history, like someone trying to make the good times last by nailing up the hands of the clock. For history is about process; the objects the process creates are incidental.'

What does Los Angeles' built environment reveal about its own civilization? "It's amazing that for all its newness, L.A.'s architecture generally stinks." That judgment, with perhaps less emphasis on the newness, could be made today; in fact, it was made in 1972, by an artist named Peter Plagens. Disgusted by The Architecture of Four Ecologies and the praise it had received in the press, Plagens took to the pages of Artforum with a thorough — and thoroughly entertaining — denunciation of the book and its author, the quintessential "chic debunker of current anti-L.A. mythology" who "finds that L.A. is really a groovy place in spite of its evils and often because of them, if you know how to look at it right." A greater Los Angeles resident for most of his life to that point, Plagens saw it instead as an environmental, political, economic, and aesthetic disaster area.

"The tragedy of Los Angeles is that just enough of the jasminelike scent of possibility lingers to render a blurry, fugitive sense of what it might be," Plagens writes, if not for "the big money-lenders, franchise operators, highway lobby, culture moguls, and reactionary politicians." Thanks to Banham, "the hacks who do shopping centers, Hawaiian restaurants, and savings-and-loans, the dried-up civil servants in the division of highways, and the legions of show-biz fringies will sleep a little easier and work a little harder now that their enterprises have been authenticated." One such enterprise, a Polynesian-themed restaurant-motel in the exurb of Bellflower, Plagens dismisses as a "miscarriage." But for Banham, the Tahitian Village embodies the "convulsions in building style that follow when traditional cultural and social restraints have been overthrown and replaced by the preferences of a mobile, affluent, consumer-oriented society": a now-lost version of 20th-century American life brought to ludicrous perfection.

To a degree, Plagens sympathizes with Banham's contrarian aesthetics: "England is a country steeped in a tradition of aristocratic, Chippendale quality supplanted by a gently socialist concern for the 'greater good' on an overpopulated island. I imagine he’s had it up to here with civil servants, village greens, planned 'new towns,' welfare state housing projects, committee hearings, the old-boy network, tweed suits, and cool, overcast days." But however genuine his appreciation of the dingbats, hamburger stands, and freeway interchanges alongside Los Angeles' more legitimate architectural pleasures, "the trouble with Reyner Banham is that the fashionable sonofabitch doesn’t have to live here." Nor would he ever live there, though he did relocate to the United States in 1976 for professorships at the State University of New York at Buffalo, then the University of California, Santa Cruz, and finally — just before his death — New York University.

Banham thus remained an outsider to his beloved Los Angeles, the position from which most of the lasting writing about the city has been done, sometimes to praise it but more often to bury it (not that it ever stays buried). On the whole, Los Angeles has been rather less compellingly depicted by its natives or near-natives, many of whom suffer from a tendency to resignation and defensiveness. (Mike Davis, author of the paranoid classic of Los Angeles nonfiction City of Quartz, hails from deep-inland Fontana, which is by some measures close enough.) The Architecture of Four Ecologies' 50th anniversary offers an occasion for readers more familiar with the city on the level of day-to-day existence — as well as familiar with the city of nearly the past quarter-century, on which Banham never laid eyes — to re-evaluate the book, praising its lasting insights but also pointing out its "blind spots."

"However polemical he was attempting to be, Banham can justifiably be criticized for writing about driving on the freeways from the restricted point of view of relatively affluent, mobile, independent, solo, white-collar-professional, alert, fulfilled, (usually white) males," writes Whiteley, lodging an objection slightly ahead of its time. But could he have written from any other point of view? It is Los Angeles' primary source of both fascination and frustration that the city, enormous in size and diverse in every sense, can't be apprehended whole. Intellectual or artistic attempts to do so usually end in embarrassment (or in at least one case, embarrassment and an Academy Award for Best Picture). The best one can do is to engage with Los Angeles through one's own, inevitably "restricted" point of view, then hope for the unlikely outcome that the result proves as appealing as The Architecture of Four Ecologies.

That, in fact, is a major lesson of Banham's entire body of work: he wrote from his own perspective, unapologetically, and from his own experience. This is as true of his architecture criticism as it is of a book like The Architecture of Four Ecologies, a prototype of what I've come to call "city criticism." For Banham, Whiteley believes, "the city was a place to experience and a place of experience, rather than a series of architectural monuments: experience and immersion mattered more to him than the disinterested contemplation of form and style." Such thoroughly Futurist experience-over-form priorities drive Banham's stated mission to "present the architecture (in a fairly conventional sense of the word) within the topographical and historical context of the total artifact that constitutes Greater Los Angeles," which creates "a comprehensible unity that cannot often be discerned by comparing monument with monument out of context."

To approach a city as an experience in this manner, deliberately and under the constant influence of all one's senses, may well require not living in it. Were Banham to experience the "total artifact" of Los Angeles today, I can only imagine it disappointing him. The tediously bemoaned thickening of freeway traffic has, to be sure, made a hackneyed joke of the anywhere-to-anywhere accessibility he described in 1971. But I suspect he would sense in Los Angeles' urban civilization as currently constituted a failure of nerve, to borrow one of his signature expressions. The architectural stakes, a key indicator, have apparently dwindled to nothing: few if any buildings put up in recent decades are daring, innovative, or even tacky enough to raise a thrill. Many new technologies have emerged, but who among us could attempt to explain to modernity-minded Banham the labyrinth of anxieties that is our 21st-century relationship with them?

Represent though they do an impressive victory over political and institutional intransigence, even the new urban trains would strike Banham as a step backward. "Don't let haters of the motorcar kid you that Los Angeles was created by the automobile," he says in one of his 1968 BBC talks. "In historical fact, the whole culture of rampant automobilism has been created in an attempt to make sense of a situation left behind by a quite different form of transportation": ironically, "precisely what is now being naively proposed as the cure for automotive evils: the electric train." But to whatever extent Los Angeles owes its size and shape to the Pacific Electric Railroad of the early 20th century, hasn't it been improved by rediscovering such older urban virtues as have revived its once-lifeless downtown, a place Banham thought "could disappear overnight and the bulk of the citizenry would never even notice"?

The only Los Angeles I know is the ever denser, more vertical and connected one of recent decades. I can hardly imagine living in Banham's Los Angeles, that car-dependent, technology-laden but patchily developed colony of Middle America enlivened by the activities of pleasure-seeking youngsters, the work of the occasional productive European émigré, and mundanely garish everyday spectacles. Yet no city but that one, which he loved with a passion "beyond sense or reason," inspired The Architecture of Four Ecologies. If 50 years have diminished the book's relevance as a portrait of the city, they've distilled its value as a guide to its appreciation. In Los Angeles, pursue your own interests exclusively and obsessively. Impose upon the city an idiosyncratic framework. Seek the central in the peripheral, and vice versa. Leave doubters in the rear-view mirror. And when you put your thoughts on paper, remember: you can never write too well.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. He created the video series The City in Cinema and is now at work on a book, The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles.

2 Comments

Thanks you so much for this amazing article about this amazing persona in the world of architecture. Banham did more to expand the breadth and scope of architectural writing than many of his classic English predecessors. The book was one of the first pocket guides to modern (sub)urbanism and wasn't a tome on architectural or planning principles but rather a fascinating field study with easily deciphered diagrams and a fresh, simple style - truly a modern book. And it wasn't necessarily meant to be read front to back but rather browsed. The book really stands the test of time - it is still new to this day and is still considered one of the best books in architecture.

Banham was my professor at UCSC and told stories of architecture with relish and suspense. He told of finding the Villa Savoye by Corbusier as if he was a guerilla soldier fighting behind enemy lines. His favorite story was about being kicked out of Arthur Clarke's car - the man simply couldn't take Banham's discussion of architecture anymore and left him happily stranded halfway to their destination. He had immense and deep knowledge of Renaissance architecture and in no boring way - the stories were animated and riveting, involving the people power and egos behind every edifice of the time. Most of all, he rode a small bicycle up the huge hill to campus everyday, a true pioneer of his time.

Banham was singularly responsible for my discovery of architecture, despite both parents being architects who studied under Gropius and Mies. He allowed me late into his class on modernism, if I could catch up on the course reading. It took under a week to read the entire course material, that's how good it was. When I later applied to architecture schools, despite my parents advice to the contrary, I found out he had submitted an anonymous recommendation, unbeknownst to me.

Thank you, Reyner - you embodied the spirit of modernism and discovery, a truly modern man.

Reyner Banham was a brilliant modern renaissance man, architectural historian, urban philosopher, industrial engineering and Design critic. There is a documentary “Reyner Banham loves Los Angeles.”

Would love to get a copy of the Lotus and the gilded Lily article (244).

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.