When its first seeds were presented in 1977, Berlin: A Green Archipelago was a quiet, prescient manifesto. Oswald Mathias Ungers and a number of colleagues at Cornell University deviated from the intellectual tenets of current reconstruction efforts, seen in the post-war development of European cities, to propose a new model for the "shrinking city". The text's idea of a polycentric urban system really took hold in the 1990s, as urban planning discourse turned towards socioeconomic considerations of ebbing and flowing growth.

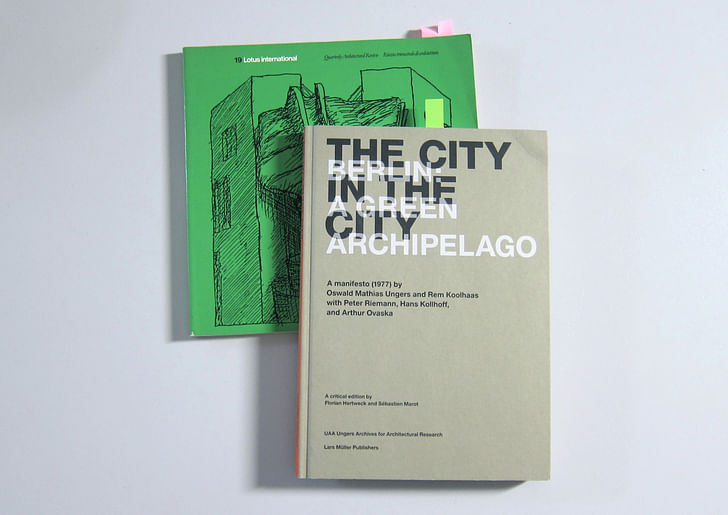

Lars Müller Publishers has now released a new edition, under the revised title The City in the City – Berlin: A Green Archipelago, featuring previously unpublished material and situating the work within Berlin's planning history. Alongside interviews with co-authors Rem Koolhaas, Peter Riemann, Hans Kollhoff, and Arthur Ovaska, the new edition features a previously unpublished version of the manifesto by Rem Koolhaas who came to Cornell, in part, to collaborate with Ungers.

Karen Lohrmann, an artist, urbanist and writer based in Berlin, jumps into this new edition after nearly forty years of urban development hindsight, to marvel at how the reconsidered text expands and informs urbanism discourse into the 21st century. Lohrmann's review of the book, entitled All things considered, digs into the manifesto's origins and its place in contemporary Berlin.

— intro by Amelia Taylor-Hochberg

All things considered (2014)

It is like reading a script that isn’t up for production. It has what it takes: the flashbacks and hints to come back to, the evidence, the little personal stories that make it all intriguing—all in tandem with the forensic work of the two editors. It is not meant to be a script but, given the development that Berlin has gone through since the fall of the wall and German reunification, a critical documentary could be a dynamic approach to navigate the Green Archipelago. A documentary provides space for evidence and imagination. It integrates the audience, it lets us develop our own scenes, position ourselves, become extras in the story. Those who have known West-Berlin during the 1970s—no matter whether through film or first-hand experience—recall the instability, the fog, the settings, and day-to-day living, and now that this critical edition has been published, may be able to juxtapose those recollections with what is happening in Berlin today, as this is being written.

LOTUS

Since 1977, with slight but as we learn crucial variations on the title from Berlin: A Green Archipelago to The City in the City—Berlin: A Green Archipelago, and its more or less direct German translation Die Stadt in der Stadt—Berlin das grüne Stadtarchipel, to Cities within the city, this work has been known as the first ever reflection on a contemporary city with The Green Archipelago instead is a reflection about a city in decline within its fixed territorydeclining population. Originally drafted for a small circle of politicians in Berlin, then published as a humble pamphlet by Studioverlag for Architektur in Cologne and at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and shortly after in issue No. 19 of Lotus International focused on the urban block, L’isolato urbano, it was never the loud or groundbreaking publication you would find on every architect's desk along with the few select others around that time. On the contrary, it was passed around among the few, very much under the radar, as if it were the ultimate secret weapon. This makes the meticulous work of the coeditors of this new publication, Florian Hertweck and Sébastien Marot, a mesmerizing endeavor.

What was mostly known as a somewhat odd contribution to that issue of Lotus took a provocative stand within an editorial selection that initiated softly elaborating on the genealogy of the urban block, but then proceeded to indeed explosive content on urban renewal which would raise many eyebrows today. The unquestioned, mainstream content of other contributors including Leon Krier, Manuel de Solà-Morales, Josef-Paul Kleihues, James Stirling, and Rob Krier, were praising ‘urbanity’ but actually plotted its erasure: all for the sake of formal exercises of dubious merit with respect to the needs of the city at the time. An array of reactionary architectural styling for a city as an isolated prisoner on life support. From today’s perspective, the Lotus editorial’s conclusion that the featured projects suggested “models” based on an already developed “appropriate theory” which “corresponds to the punk view of post-modernism,” is indeed disconcerting.

REALITIES

Hertweck and Marot began work on this book almost six years ago, shortly after the death of German architect Oswald Mathias Ungers, in 2007. Until then, Ungers was regarded as the lead character behind the work. Nearly twenty years into the redevelopment of Berlin since 1989, in the wake of an armada of competitions, political agendas, massive master- planning and the resulting evidence, and over 35 years after the first publication of The City in the City—Berlin: A Green Archipelago, Hertweck and Marot have opened an archive revealing many narratives, contradictions, vanities, and odd ends. Now, along with the editors, we must reconfigure our view and expectations of this proposal.

Hertweck and Marot cannot have known what was to come, instead found themselves piecing together possibilities, trying to get to the bottom of many lines of thought. They highlight the gaps and offer them for interpretation, letting us catch a whiff of what was on the This text clearly specifies the need for urban editing rather than urban planning.horizon then. Those who know Berlin today, will agree that their work makes the worlds of local politics, economics, and the usual interests much more comprehensible. Just as we begin to understand the other that the city has become, they point at the realities that made, and make, it happen. So, all things considered, this publication on the Green Archipelago must be on our desks today.

We learn that the proposal was the byproduct of what was officially one of three summer schools, organized by Ungers in collaboration with Rem Koolhaas, Peter Riemann, Hans Kollhoff and Arthur Ovaska at Cornell University. Ungers had strong ties with Berlin where he had taught at the Technische Universität, during the 1960s, developing a range of more thought- than action-provoking approaches to the city’s fabric. This 1977 summer school was entitled The Urban Villa and focused on Berlin. It followed the 1976 summer school The Urban Block directed at New York City, and preceded the final one on The Urban Garden, again focused on Berlin, in the summer of 1978. Positioned prominently in the original eleven theses published in Lotus 19, the Urban Villa as a topic at first seems alien in the context of the others. Compared to the bold message of the Green Archipelago suggesting a city of many islands instead of one condensed center, the Urban Villa is an aspect which really surfaces only after 1989, when the array of leftover urban typologies rises to transient prominence as the world begins to understand Berlin’s abrupt blueprint. Today, the local code of the Urban Villa, clearly outlined in 1977, has long been diluted into the vastness of other urban connotations of the ‘new’ Berlin, from Berlin Upper East Side to Palais Belle Kolle, signature forums, carrés and experiences, in other words quotations. The Green Archipelago instead is a reflection about a city in decline within its fixed territory, marking a new debate on cities and the cultural landscape beyond territory that developed simultaneously—clearly the context in which Berlin was operating then.

POLARITIES

That the Urban Villa turned into a side act of the proposal puts the focus on Rem Koolhaas. Upon his arrival in Berlin in the summer of 1977, he confronted Ungers with Berlin: A Green Archipelago, a six-page typescript which opens with the words, “Any future ‘plan’ for Berlin has to be a plan for a city in retrenchment.” This text clearly specifies the need for urban editing rather than urban planning. In other words, working with what has remained of the city—a mix of wilderness, interruptions, better or worse remnants of city fabric and single monuments, with the addition of ‘retroactive architecture’ such as Leonidov’s Palace of Culture, Magnitogorsk, or Mies van der Rohe’s skyscraper for Friedrichstrasse, to be viewed as a contemporary dualism or, as Koolhaas put it, a “polarity Nature-Culture or Nature-Metropolis.” He further elaborated on a system of nature as synthetic and “an environment completely invented by man”—a line of thought that in recent years has driven the cultural debate on the era of the Anthropocene. We are offered a glimpse of the early Koolhaas deeply immersed in Delirious New York which would be published only a year later, and thus gain access to his approach on the city as manifesto instead of cities based on manifestos, on the city as an intricate and immersive system as opposed to a static somewhat decommissioned given.

TRAILER

At one particular moment—and this would be the fiction part of the documentary—there must have been the decision to turn this document into the framework of the entire summer school, which as we learn is only the facade, or trailer, for a much greater endeavor: that of winning the directorship of the Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) on the Berlin horizon for 1979. We learn that from the beginning, this was a highly political proposal for the future of (West) Berlin, something impossible to conclude from the version published in Lotus 19. In those years, the Wall had sunk into the psyche of Berlin and the world, and no one would openly consider its implications for the future. The political comes into the equation only now that we are offered the much more comprehensive and contextual take on the same proposal through Hertweck and Marot’s work. Their interviews with protagonists Koolhaas, Riemann, Kollhoff, and Ovaska manage to clarify that Koolhaas’ original typescript was never circulated during the summer school. Instead, in a back chamber, it was merged and the city as an intricate and immersive system as opposed to a static somewhat decommissioned given.blurred to the extent of defusing it, to make it work for local politics and universal acceptance. Koolhaas’ original Green Archipelago never resurfaced after he presented it to Ungers that summer. Koolhaas himself did not keep a copy. Instead, Hertweck and Marot have found it between files in Ungers’ archive, along with the full array of rewrites and the final published version. This indeed exquisite corpse rests well along with the many other stories on a desperate Berlin constantly attempting to reinvent itself.

The interviews further reveal that none of the protagonists believe, nor did they believe at the time, in the potential of the overall proposal as a response to what the city was becoming since the 1960s, no matter if Cities within the city (the Lotus 19 version) or Berlin: A Green Archipelago (Koolhaas’ original manuscript). In Europe the Architettura Radicale movement had already staged their critique on laissez-faire and total control in multiple ways, and East and West Berlin were among the playgrounds for variations on both. American cities had been reality-checked, rendered as ‘ecologies,’ and declared territories for ‘learning,’ at once admired and despised. Still, or maybe because, it is 35 years later, all four protagonists, in their own way, consider The City in the City—Berlin: A Green Archipelago only as a conceptual exercise, a political campaign, a film script, utopia.

INSTABILITY (OR: GREATNESS)

This confirms the initial suspicion that after all, none of this ever really concerned Berlin as a specific case, but much more the shaping of individual curricula. That neither Ungers nor his collaborators seriously reviewed it, especially in the years of loud debates following the fall of the wall, only underlines the confusion and desperation in architectural thinking at the time. One reason may be that the Green Archipelago stands for an attitude according to which much is possible, with or without much effect, a virtue not to be underestimated given our event and entertainment doped perception of culture today.

This indeed exquisite corpse rests well along with the many other stories on a desperate Berlin constantly attempting to reinvent itself.That the discussion has shifted, even given the diverse domains in which we operate, beautifully surfaced with Berlin-based periodical 032c’s fourth edition headlined Embrace Instability, published in the winter of 2002. The editors suggest to celebrate “the unstable states where everything can happen,” and feature a selection of black and white photographs by Michael Schmidt titled West Berlin 1980s. Schmidt’s visual material, in its most fragmented way, eerily evokes the atmosphere of the summer of the Green Archipelago, 1977. West Berlin was an icon, no more no less, and as such it cruised worlds and minds, becoming a set for all kinds of strange encounters. This series, despite its ten year production period between 1976 and 1986, is the ultimate set to immerse us in Berlin then and now. A sea of possibilities—if you can handle it.

Striving for a return to ‘greatness’ is an uncanny substitute for everything that this city doesn't need. What it Does to Your City was the title of Cyprien Gaillard’s performance at Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon in September 2012. A group of caterpillars digging away with expressive gesticulations lit up by fireworks, blurred by smoke and fog, all driven by the beat of massive xylophones. Revisiting the scene the next day, one sensed an almost appeasing dystopia. We know, all has turned out to be very different from what was anticipated back then. A provisional perfect ending for a documentary.

— Karen Lohrmann, artist, urbanist and writer, based in Berlin. She monitors, depicts and interprets landscape, from terrain to territory, from premise to significance. The notion of abandonment is at the center of her investigations touching issues of nature, entropy, laissez-faire and total control.

Karen Lohrmann is an artist, urbanist, writer and curator who focuses on editorial processes as critical and projective tools in landscape visualization. She trained in architecture, art history and scenic design at Aachen University, ETH and University of the Arts in Zurich, and TU ...

11 Comments

I just pulled it out from my friend's library.

I can see how this established innings to Rem's Delirious NY seeing penetrability of Manhattan mainly through its grid. Which was my research inspiration in 1980, studying in NY.

Orhan I just read in the Elia Zhengalis interview in Log 30 that Rem had more to with this publication than I think Unger? Would admit. Not at home to double check the text and if I am not mistaken the Berlin Wall was Rem's thesis project?

from LOG 30 - page 80

"CD: In 2006 Rem and Hans-Ulrich Obrist interviewed Mathias about his life and work [see Log 16, 2009]. They were going to do a series of interviews, but Matthias died. now there's a new book on the Berlin Green Archipelago, by Florian Hertweck and Sebastien Marot, which documents that Rem had more to do with it than Mathias credited him for.

EZ: That's correct. It was really Rem's project - and at a time when Matthias was captivated by Rem. Matthias would never admit to that, but I know that the entire archipelago concept, and all its implications on the territory, was Rem's..."

CD = Cynthia Davidson

EZ = Elia Zenghelis

I'm almost certain now, beyond the quote above - SimCity was based on Rem's brain

that's an Archipelago top left partially behind the SimCity toolbar...

that screenshot is perfect. hyper delirious.

As a kid and teenager I lived in Berlin from 1983-1991. Traveled and worked there from 1999-2000. In NYC living and working 2002-now. Just realized after reading this a 2nd time I think that I have spent a good part of my life in Contained cities - leading to having lived in "edited" cities as this post covers. As an architect I prefer "edited" over excess that allows flexibility. (Another Rem reference-dutch prison design entry and text). As a kid we used to visit a Texas born opera singer who I guess if I remember correctly was in the Berlin opera, patrons gave her Mercedes as gifts...to get to her house we would drive a stretch in Berlin that was literally a road between border fences to the east. Her house was clean and modern and in what I would have called a suburban forest - tall trees with branches up high. It was like nothing else I knew of in Berlin, I lived in Steglitz (Friedenau) and went to school in Zehlendorf at JFK. Orhan - hyper is the right word, nothing in Berlin as a kid seemed hyper, but Manhattan by all means does. Decline vs growth I guess. Need yo go back, its been 12 years...wondering what happened to places like Teufelsberg..went sledding there as a kid. Enjoyed the red - vielen dank.

Re. Quondam's comment: I’d say the historical ellipsis is rather a reality check. I am aware that there was a time when developments such as the ones proposed in Lotus 19 were seen as the grand solution—likely hoping to follow up on the numerous experiments that were proposed already in the late 50s and shortly after (f. ex. the Hauptstadt Berlin competition 1957/8). I don’t think anyone can tell whether these earlier (unrealized) proposals would have succeeded—although I’d like to think that—but knowing the city well from times before the Wall, and living in Berlin since the early 90s, I can speak to what is “functioning” here, now. The “here” is important in this case. So is the “now”. Much of what is presented in Lotus 19 has, mildly put, diminished to places of social and spatial unease. I agree it looks good, especially in b/w photography and line drawings. Let’s say it was a test, and that it has failed. It wouldn’t be the first one. One thing is to publish all kinds of references, analysis and of course the good intentions, another is—especially in architecture and urbanism—to revisit the scenes. Should you visit Berlin in the nearer future I’d be happy to continue the conversation combined with a reality-checking walk.

Re. Orhan's and Olaf's: do get the original draft written by Koolhaas. Not only is it beautifully written but a proposal still to be considered. We might only get ready for it now (or very soon). Olaf, thank's very much for the source.

Re. Chris' comment: Great flashback. Almost a script, somewhat Fassbinder scenographic. Teufelsberg is there and still a known spot for grim winter days. Time for a revisit. It changes very very fast ... no comment on which way it goes.

The content of Lotus 19 is unquestioned—today. That is what I am referring to. Given your impressive knowledge of Berlin I am sure you are also familiar with the discussion that has taken place since the fall of the Wall, the Masterplan, the new 'steinerde Berlin' or even 'Teutonia' as Arch+ once called it.

The positions proposed in L19 are not part of the conversation today, or in other words, there hardly is a conversation, except for the attempts of Arno Brandlhuber et al to actually initiate a discourse. So, if at all, today, these proposals come down as mainstream. I don't know if you have read the re-edition of the Green Archipelago, the book I am actually writing about in my text, but I suggest to dive int the interviews with Kollhoff etc. (actually especially that one) to enjoy the new way of thinking in the 'new' Berlin.

I am not overly interested in architecture per se. I look at what architecture does to urban space and other spaces, and people. That is where my criticism is headed. Regarding the walk I suggest: No, why look at that? As said, it takes more than looking at architecture. Once the moment comes I will suggest a route, just so that it will be a real reality check ...

Thanks for responding and will be getting a copy...it feels these days like contemporary architecture theory is completely saturated by Koolhaas...

Great article... nice and useful... I am doing my doctorate study about Exodus project, interested in cities inside cities, it includes an interview I did to Elia Zenghelis about this project. Any kind of info like this article is great to know in this kind or urban research. Trip to Berlin 13-14 Agoust 2019.

My mail is

mingo.merino@gmail.com

Domingo Merino, architect

Madrid, Spain

Domingo,

Thanks for your attention. Unfortunately, I'm not in Berlin these days. I'm not sure if I can be of further help to you but let me tell you that asking Stefano de Martino, one of the earliest associates of OMA, about your focus he suggested to surely focus on Elia and, if possible, Rem, for information. Also Madelon Vriesendorp would surely be a great source. Stefano joined shortly after Exodus.

With my best wishes for your endeavor,

Karen

IT sounds great

Thanks _A lot anyway!!!

mingo.merino@gmail.com

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.