Recently I experienced a changing incident with a professor who was reviewing my work alongside that of my classmates after a pin-up. He was excited about all the work and decided to issue individual comparisons to architects in the field. He went down the line commenting to my [white] classmates: "You could be like Eisenman,” "You could be like Frank Gehry," etc. When he got to me, he failed to think of an architect who looked like me, and instead said that I could "be like Obama," because there aren’t many black architects.

The total number of black architecture students has remained at or near 5% for nearly a decade. As this number shows, my experience in this classroom as the only black student is not unique and the lack of representation has been commented on frequently by fellow practitioners of color.

Professionals in the Field

Mark Gardner, Principal, Jaklitsch / Gardner Architects, expresses a similar experience: “You have to go to classes where you might be the only one in the room who looks like you. That's not a bad thing, but it's a tough thing.”

Phil Freelon, Managing Director and Design Director, Perkins+Will North Carolina, said: “I have experienced and observed [instances] of discrimination and inequity at every level in the industry. There are moments that are quite blatant, and there are the unintentional consequences of the economic strata in this country. Take academia, for example. Say you have an African-American student coming [into architecture school] who is starting with a subpar high school education as a consequence of where they grew up. You're starting at a [disadvantage] to begin with, and it's a rigorous curriculum. There may not be a mentor or another student who has been through [a similar experience] and can help guide you. You feel kind of isolated.”

Suchi Reddy, Founding principal at Reddymade Architecture & Design expressed how deeply ingrained this experience is in the U.S.: “It's pervasive. People don't even know they're doing it, but hopefully, there is a generation coming up that's bred out of this. I don't think there is that much malice in it; I think it's very much a residue of being unaware.”

These are sentiments which resonate with how I feel daily in each of my classes, a feeling I can only liken to a kind of paranoia. I feel it’s harder for me to communicate with my professors and truly get understanding. When my work is critiqued differently from everyone else’s, even if they have much less work done, I try to make sure I don’t let myself think it could have anything to do with my skin tone. I see students building relationships with professors outside of class, yet professors rarely come by my studio desk or chat with me outside of class. I wonder why, before convincing myself that maybe it's just me not being outgoing enough. I end up feeling isolated. My paranoia, that I am getting looked at and judged differently than my classmates because I’m African American, always has a way of being proven as reality. That quick moment, where I was compared to President Obama, became a moment of tokenism, and made me feel like my isolation was on display for the class as a joke. I wasn’t able to get the thought and feeling out of my mind for days until, finally, I emailed my professor to let him know that what he said had affected me.

I had anxiety about sending the email because I had to deliver it bluntly. I needed him to know exactly how that moment made me feel. But I also wondered what would happen if he didn’t agree or understand my point of view, and thought I was just being sensitive and pulling a race card? I was worried because, at this time, I had absolutely no connections in the architecture universe. If he bad-mouthed me to colleagues because of this incident, I had no one on the inside to defend me or speak on my behalf. I need all the connections I can get to be able to eventually land an internship. What if he responded nonchalantly, or worse, negatively, and I still had to interact with him every day?

Should I just let this go?

I can’t.

Luckily, after receiving my email, he wanted to meet and discuss the issue in person. He was very apologetic and understanding. He offered to mentor me when I explained how I feel at school. He also encouraged me to write about the situation. During our conversation, he asked what my experience and struggles are in architecture school and how I think they are different from my classmates. I began with my work schedule.

The Difference

I don’t mind being the only one who looks like me in the room, but there are a lot of challenges behind it. I am the only student in my class who has to work full-time, 50 hours a week at least and sometimes more spread among 4 jobs. I am the only student in my class who does not own a laptop or have a computer at home, which means I have to use the computer lab at school, which is open only from 7am-12am on Monday-Friday and 10am-8pm on weekends. I am the only student in my class who doesn’t have a professor in the architecture program who is of the same ethnicity. I am the only student in my class who has never met an architect who looks like them. I am also the only student in my class who has NEVER, over the course of my two years of graduate school, been shown work by someone from my culture, a Black architect.

“What often happens is the people who have access to money are the ones who continue to get pushed forward,” says Germane Barnes, designer in residence at Opa Locka Community Development Corporation. These racial and socioeconomic differences between my colleagues and I will not end upon graduation. The work schedule I have to take on is due to my financial situation: having to work to pay my bills. Consequently, every hour I am working is an hour I am not developing my craft. That means 55 hours a week are being taken away from me developing as a student and as an architect. That is also 55 hours a week less than my classmates who are able to study and complete work. So, what will my portfolio look like compared to my classmates/competition?

The fact of it is, there are often times where money can buy you a better portfolio in architecture school. When I am building my models 100% by hand, because I can’t afford to save the time by paying for a 3D print or outsourcing a laser cutting appointment, I question if the playing field is level. One of my jobs is in the computer lab on campus. I watch people who pay $15.00 per print, mess up 1, 2, 3, 4 times, and keep printing and paying for a new sheet until they get it right. If I mess up on a print, then I am shit out of luck. I have never had excess money to reprint. All of my work has to be perfect the first time; I literally can’t afford errors. I had midterms last week, and the day before my presentation, I had to leave the architecture studio and drive for Lyft for 4 hours so I could afford to pay for my print and buy enough materials to begin to make a model. I’m not going to get into my spending habits but just know, I am spending money on nothing that is not a necessity in my life.

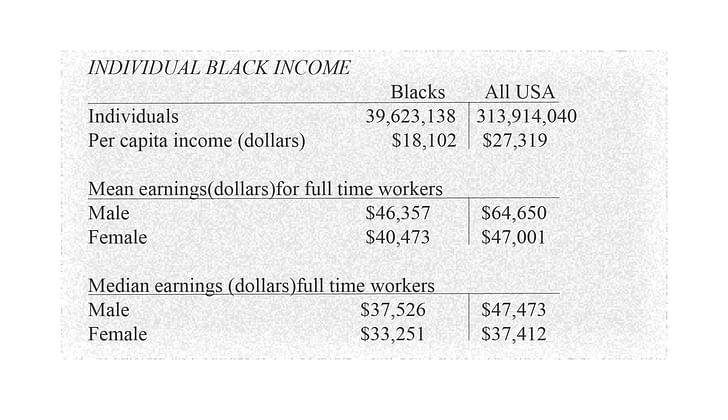

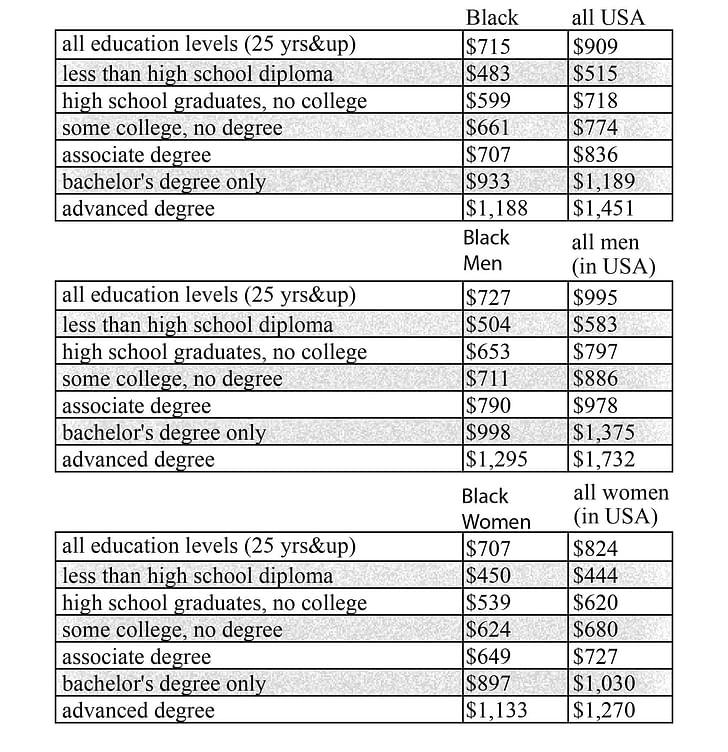

This major schedule difference between most of my classmates and I has to do with the fact that many have help paying for school and/or living expenses. I am paying for school on my own. I have a shitload of loans; Maxed out. By the end of my Master’s program, I will have a balance of over $130,000 in debt to repay with my undergraduate loans included. My family isn’t able to help pay for my education. My parents are very hard workers and have respectable professions. Both my mom and dad are high school graduates. In terms of wealth, my family is statistically in a very common situation for Black people in the U.S. with a high school degree. Most students who grew up in a family like mine will be in a similar situation when attempting to pay for school. I won’t dive too deep into the root and causes of this disparity in income, but I feel it is important to see the statistics about African American people’s income in comparison to the rest of the country.

I am also the only student in my class who has NEVER, over the course of my two years of graduate school, been shown work by someone from my culture, a Black architect.

After all of this, I am still constantly asked questions such as: “Why don’t you have a laptop?”; “Why don’t you have a camera? You’re an architecture student.”; “Why are you working so much when you are supposed to be focused on school?”. Look, if there was absolutely ANY way I could, I would. I’m not working to maintain a comfortable lifestyle, I’m trying to survive.

This is by no means meant to be a “poor me” type of article. I fully believe these disadvantages I face now, will end up being my advantage later in my life, and I use it to fuel me now. It gave me a chip on my shoulder, and I embrace that. It brings the competitor out of me. It inspires me to get licensed, and to become an inspiration for someone else who will have to walk this same path. There are no words that can explain the feeling of seeing someone who looks like you thriving in a position you hope to attain; To know there has been a path set by someone like you that you can follow. I do want to express this which is an uncommon circumstance to most, but a common situation for many African American students entering into professions where they have always been underrepresented. According to the National Architectural Accrediting Board, the total number of black architecture students has remained at or near the 5% mark for over the past decade.

I hope to spread light to my school faculty and faculties across the U.S. I want this article to influence professors to actively seek to get to know their students and backgrounds. I also want to raise the awareness of the decision makers in the architectural world in regard to the different set of challenges that we are going through. Most of all, I want to let the students who are in the same situation as I am in any field, know that they are not alone because I am definitely not the only one. Don’t let people who misunderstand you tell you what you can be. Don’t let the low odds dictate the heights of your success, because we are not the cause of our situation, we are the effect. We aren’t like our classmates, we are in a different race. We aren’t in a sprint, we’re in a marathon.

I also do not want this to influence a principal at an architecture firm or an admissions counselor at a university to go and find an African American architect/designer for their firm to fill the quota. We really don’t want to be hired or accepted purely so you can check the diversity box—to be the token Black at your firm or school, in other words. I personally want to earn my position based off of my merit. As I become more and more knowledgeable in the field, I realize that my culture’s narrative is not present in architecture, but it should be. African Americans make up over 13% of the U.S. population. Isn’t architecture supposed to reflect society? If that is true, then why is what we are learning in school almost entirely Eurocentric?

We aren’t in a sprint, we’re in a marathon.

In an article recently published on Curbed, architect Mabel O. Wilson of “Studio &” stated: “The discourse impacts how people, once they're admitted to an institution, learn the discipline. Because that discipline is already racialized to the point where you're alienated. It's just like questions around gender. If you don't already see how patriarchy and misogyny are embedded in the ways in which people write and think, bringing women to it isn't going to change it. You have to fundamentally do both.”

I am only two years into the field of architecture, but I am in love with everything about it. I always tell my Mom that it feels like I am in exactly the right place and the wrong place at the same time. I have attended 5 architecture/design conferences in Los Angeles, and each of these times, I was the only Black person in the room. I felt a bit of apprehension and anxiety about writing this article. I didn’t want my introduction into the architectural universe to be focused on race. But in the two years that I have been in my M. Arch. program, I have realized that if in 2019 I am compared to a former president of the United States because my professor doesn’t know any African American architects, then something needs to be said, and something needs to be done. So what are we going to do?

Demar Matthew is a Los Angeles based architectural designer,theorist, and creative. Demar is the founder and Principal of OffTop Design. He also works with A+D Architecture + Design Museum in Los Angeles as curator/exhibitions associate.Born in Moreno Valley, CA Demar received his Bachelor’s ...

1 Featured Comment

Demar,

Thank you for writing this, I deeply appreciate it. I'm currently a third year undergrad black Architecture student, and have felt this in the totality of my education, especially being in one of the whitest cities in the US. I don't think could have articulated the emotions and significance of this in my own words, and almost began crying during it. I've been struggling to cope with this fact or explain it to my classmates and colleagues over the last 3 years, and I'm happy to have this piece of writing to share and with much hope, it resonates and others can finally understand. I am at a loss of words, I just needed to make sure I said, Thank You

All 13 Comments

Demar, this is a very special and relevant piece. And I appreciate your point on this not being a "poor me" type of article. Yes, it is true that as a black man in this profession and in this country that you are at a disadvantage, it's not something stemming from campaigning but rather something that is deeply rooted in history. While the condition for black ambition is exponentially richer than it was during the civil rights movement just over 60 years ago (that's so recent in the grand scheme of world history) there are still unavoidable ripples from that stain on our nation existing today. I mean slavery was only abolished 154 years ago.

I identify with many of your points here because I, as a black man, have experienced some of what you express here. But after 8 years in the profession I can tell you that, at least in Southern California, the yearning for inclusion is genuine. However, you will find yourself being presented opportunities merely because you are black. It will be based on your merit but your blackness will play a role in people's decision making as well. It's just how it is, it doesn't have be a malicious thing on their part, but it is an inescapable part of our culture today. This used to bother me but one of my mentors (from Woodbury) told me years ago:

"Don't be a proud fool, if you can get an advantage then use it and show that you were the best person for the job all along." Essentially he was saying that my preoccupation with wanting to be chosen for a position solely based on my merit was naive, and he was right. Most opportunities will not consider an unqualified individual but sometimes your being black will make choosing you easier. So, yes, your merit is still a factor, but the fact that you are a minority is also. Just having that awareness gives you power.

I could go on at length about what you've written here but I'll send you a private message. Thanks again for the article!

Yes! "Just having that awareness gives you power" is a word that should be shared more often!

Demar, great article and very enlightening. I had never thought about what a burden paying for school must be with all this computer stuff. (I went through when you needed to buy leads and paper). Your work ethic and struggle will serve you well as the working world can be just as tough politically as school is financially. Being hispanic I can somewhat empathize with being the only minority in the room.

Great architecture is universal. Yes, the forms might come from a particular culture, but like music, if you can play a fiddle you can play a tune. Meaning, there are many times a style or look will be dictated to you by a client, the context, the budget, or whatever, and you still need to make the best of it. Your task is to drink from each fountain of knowledge and broaden your skill set in the process. As far as what to do, all I'll say is try not to think about race too much or you might miss the lesson being offered. People will always find reasons to not like you that are out of your control. What is in your control is how you handle them, especially if it's their hang up.

"I am also the only student in my class who has NEVER, over the course of my two years of graduate school, been shown work by someone from my culture, a Black architect."

Maybe you define your culture by race and I won't challenge that. I'd simply say that your culture is probably more white than you think just as some white people have more black culture than they think, assuming we can quantify these things. Again, as an hispanic, I'm American first, so I'll not only claim England's Magna Carta and the Constitution, but Roman, Mayan, and Japanese architecture. Define yourself however you feel comfortable, but underneath it all, we're the same, whatever people say.

Good luck and keep plugging away.

problem 'splained away...

Hello Demar,

I feel your pain. I was fortunate and went to a HBCU where I did get the nurturing that was needed for me to get through school. However, I am a Black and female. I was the only one to finish in my class and the numbers are even more staggering when it comes to registration and representation in the field. It's even worse. It saddens me that at this time in our country that we are still struggling with this. You are very young. My son is 44 years old so that gives you an idea of how old I am. Hang in there! It is a passion worth fighting for. I suggest that you get in contact with your local NOMA (The National Organization of Minority Architect) Chapter. There are a lot of us out there that can advise, encourage and direct you; licensed and unlicensed. Here is the link to the website. https://noma.net/

Follow your dreams. Difficulties breed innovation!

This is a wonderful and personal glimpse into the challenges you face, Demar, and I'm so grateful that you wrote it! Just this week I read a quote about the many small challenges that might not seem overwhelming individually but that all build up over time: "A ton of feathers still weighs a ton". Good luck carrying all of it.

I will point you to two things: One, this incredible interview on Archinect Sessions with Phil Freelon. He is just the coolest and so straightforward about the challenges Black architecture students face. https://archinect.com/news/article/149995005/an-american-story-a-conversation-with-phil-freelon

But he also mentions the AIA, and, in reference to your comment about attending conferences at which you are the only Black architect: Every National AIA event I have been to has a significantly higher number of Black architects in the room than any other architecture-related event I go to. As Phil Freelon says, the Black architects who *do* achieve registration tend to be high-achieving in all realms, so they join AIA and move up the ranks there, as well. The AIA is FAR from perfect, but I have met many more Black American architects through it than anywhere else (except NOMA, as Anita mentions above).

OK, so actually three things: the non-profit PUP that I do work with is running a speaker series this spring that focuses on inclusivity in design and our speaker line up is excellent: https://peopleup.org/blogs/news/daylight-season-two-inclusive-design The graphic on this page is out of date but our fourth speaker will be Maurice Cox from Detroit.

Diversifying our profession is hugely important if we want to stay relevant.

Wow, this identity politics has to stop. When I tell other people I want to be like Zaha Hadid I don't mean I want to be a woman or Iraqi (which I am neither), I mean I want to be as good of an architect as her.

In architecture school, all my professors were white and as a Hispanic that didn't bother me.

Good for you.

Juan: #YourSlipIsShowing.

Signed up specifically to make this, “his” one and only comment. Not a real person.

With a name like Juan Valdez...ay dios mio!

Mr. Bell, there is such thing as a first comment.

I think you're an asshole. Your takeaway was about the setup, which imho is the best way to talk about broader issues in the profession, is not what the piece is about, and only goes to my prove my point; you're not right for this profession.

Thank you for writing this Demar.

The built-in obstacles because of race in America, and Canada where I am from, are undeniable. They exist in Japan where I live as well, but its a different story here, because Japan is not going to change any time soon. I have hope for North America, and articles like this feel like part of the way forward.

A lot of us who benefit from the current system are ignorant. Showing us the bullshit will I hope at least make us a bit less idiotic in our thinking. The assholes maybe cant be helped, but it would be nice to think that enough of us will get a grip so, at the very least, we don't say fucking stupid things (that Obama comment is crazy as).

I wish change would come faster. In the meantime please keep on writing!

Demar,

First of all, congratulations on the pursuit of your architecture degree. It is no small feat to obtain a degree in architecture even under ideal conditions. While you are absolutely correct that there are few African American architects, let me point you in the direction of two pioneers in the profession that have made their mark.

One is Paul Revere Williams, an early pioneer who practiced in Hollywood and designed the homes of many celebrities while also facing unnecessary adversity. And the other is David Adjaye, who is arguably the most famous practicing black architect today. If you have not heard of him, he is an award winning English born man of African descent who designed the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC among other notable work.

So, guess what? You could be like Paul Revere Williams or David Adjaye!

https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/the-architect-of-hollywood/

http://www.paulrwilliamsproject.org/

http://www.adjaye.com/

Wow. Thanks Demar, for sharing this powerful reminder, and its effect on me this morning.

What a blessing for both of you in the exchange with your professor, and his reaction to being illuminated.

I grew up in the South and witnessed rampant discrimination that we as a society try to pretend isn't there anymore. And in college there, saw painfully similar circumstances of the few black students in my architecture school. Because of those observations, in my professional career that has included recruiting and staffing operations over many years, I've leaned towards the disadvantaged, the overlooked, and the underdogs in a variety of forms and with difficult stories. Those people deserve a break, and tend to have developed strong character and grit in the face of disadvantages.

It was appalling to me in architecture school, and still is now with this story as a reminder, that we as a society cannot better finance a college education for someone already disadvantaged, and now has to work 50 hrs./wk. and doesn't own a computer. Many of us are not sure what we can do as individuals about that, but I and everyone who reads this can influence the awareness of those immediately around us in our own little circles, and maybe we can slowly put a dent in this problem... one person at a time. In the interim I hope Woodbury or the state of CA will be embarrassed into action, and an angel will drop a laptop on your doorstep in the near future.

Just yesterday I watched a video link about Arnold Schwarzenegger's journey from an abused child in Austria to landing in the US with $20 and a funny accent, and picking himself up through odd jobs and little businesses before landing the Terminator role, and going on to be a Governor. One of my first thoughts after 'great story' was that he was not black.

Please keep doing what you're doing. Too many of us are inspired by your story.

And when the time comes, please activate yourself in the AIA and NOMA.

We need those voices and stories.

Demar,

Thank you for writing this, I deeply appreciate it. I'm currently a third year undergrad black Architecture student, and have felt this in the totality of my education, especially being in one of the whitest cities in the US. I don't think could have articulated the emotions and significance of this in my own words, and almost began crying during it. I've been struggling to cope with this fact or explain it to my classmates and colleagues over the last 3 years, and I'm happy to have this piece of writing to share and with much hope, it resonates and others can finally understand. I am at a loss of words, I just needed to make sure I said, Thank You

since you are aware of the Directory of African American Architects, have you reached out to any of the listed architects who are local to you or to the SoCal NOMA chapter? Both could be sources for mentors and support for you.

Talk to your school and have them sponsor you to attend the NOMA Conference which will be in Brooklyn, NY this year. If you want to meet architects who look like you there will be about 900+ of them in attendance. I have been an AIA member for close to 20 years and I have been a NOMA member for 25 years. NOMA is the only reason I am a practicing architect today.

Did you ever consider attending an HCBU? My daughter is applying to architecture programs now and know unless she attends an HCBU she will probably have a similar experience.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.