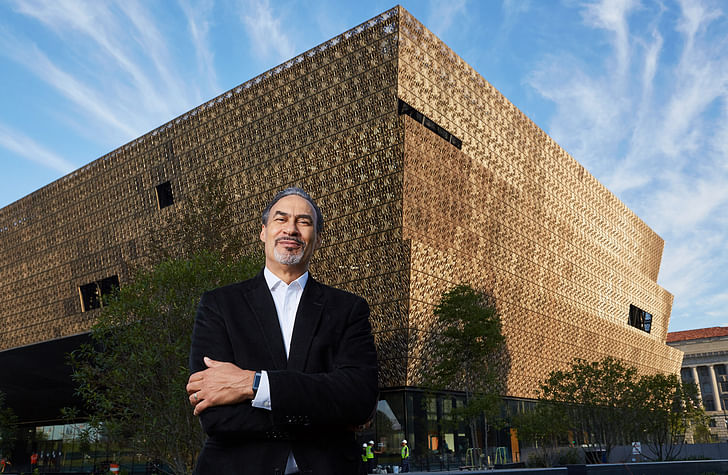

This week brought the sad news of the Phil Freelon's passing. Our conversation with Mr. Freelon had quite an impact on us when we recorded the conversation two years ago. Before our recording we had already understood his incredible talent as an architect. Hearing his story, first-hand, however, was humbling and deeply inspiring. Before sharing the full-transcript of the interview, I'd like to share my co-host Ken's comment he left upon reading the news of his death...

Optimistic, even with the deck stacked, the consummate professional, a pragmatist; a hopeful pragmatist.

When I listened to the podcast today, after hearing of his passing, I remember thinking how easy the conversation flowed, how present he was in the moment - we never sent questions, or expected anything longer than 20 minutes, he gave us 40. We did our homework, knowing that given the timing, it may have seemed like we wanted to talk his ear off about the NMAAHC, but the richness of his heritage, the time he came of age, his interest in sci-fi - the forward thinking of Star Trek - his family; wow. I knew of Phil Freelon before I knew about Paul Revere Williams, and Phil's leadership in getting Mr. Williams his AIA Gold Medal is the kind of selflessness that is rare to find these days, yet easy to see why it rested so comfortably with Phil; he saw the forest, the trees, and sought to lift those left behind by a profession's ongoing struggle reconcile it's values with it's past missteps.

Phillip Freelon, talked in the podcast about his present, and future self, spoke not only about accessibility in terms of codes, but of universality, he spoke about the dignity of all people, regardless of ability, of race, of gender, of nationality, identity. He spoke about a world, a world he saw in Science Fiction, of Roddenberry, but he spoke about it in a way that made it seem nearer than any star, more realizable than any fiction, and more importantly, at least for me, he spoke like it was just around the corner, and he was going to be here to enjoy.

I was fortunate to meet Phil and his beautiful wife Nnenna, it was brief, but it was the honor of my career to have had the chance to meet him.

When I think about my choices in this profession - and I think a lot about them, and wonder why I am doing this - I get self-involved, loathsome, self-pitying, but when I reflect on the man Phil was, and what he meant to so many professionals, and to so many communities, and that photo above - man, I've never seen an architect and their spouse radiate so much grace, and love - I want to be like Phil, and see the world he saw, be the architect-leader he became. We need more Phillip Freelons, because the one that has passed, has awfully large shoes that need to be filled.

- Ken Koense

Ken Koense: Hi Phil, this is a Ken from Minneapolis. A few weeks ago I was reading an article about you and many things came to mind. The interviewer was talking to you about the Smithsonian Museum and the one thing that struck me, because we've had a lot of discussions here on the podcast and we've had some online discussions as well, was that Freelon Architects has specifically stated that they would never design prisons, casinos, strip malls... and they were primarily focused on libraries, museums and schools. Could you talk a little bit about why it was that you've made that very specific effort to not design those types of facilities?

Phil Freelon: I would turn that around a bit and tell you that it's what we choose to design more so than what we don't. And I only list a few building types to say that's not our specialty, similar to other professions. Let's take the medical profession, for instance, you're going to have doctors who specialize in cardiology, radiology, podiatry or whatever. There are so many disciplines and you can't be all things to all people. And when I started The Freelon Group I decided that we would focus on the things that were of interest to us, and that also contributed positively to the communities in which they were built and that we could feel good about. The project types you listed fall into that category. We feel like designing places where people are educated and go to discover art or learn about other cultures. These are the kinds of architectural projects that we're attracted to and that's what we chose to focus on over the course of my career.

Donna Sink: Is that what you started with right off the bat when you first started up your own firm? Can I ask about the very early days when you started as just an office of one?

Phil: Sure, yeah. Well even before then because I had been practicing for 14 years before I started my firm and the firms I worked with I worked on the kinds of projects and we talked about lots of those firms did those things exclusively. That's where my interest was and that's where my experience began to build. And so it made sense starting my own practice in 1990 I would build on the experience from over a decade of being out there doing that kind of work and building relationships with the clients and building expertise. So as one person, and then two, then five, and ten and so on, we just built on that. I started off with little school additions and renovations and things of that nature, just as most practices would, starting from scratch, and you just evolve over time, gain expertise and hope to expand into larger and more interesting projects. And that's what's happened.

Donna: You said you started in 1990. Weren't we in a pretty awful recession then? That's when I got my first degree and it was impossible to find a job as I recall.

Phil: That was an interesting time. I actually stepped away from my prior firm in January of that year, and the economy was looking great. The Gulf War hit during the summer. I remember looking back, not too long ago, at my business plan and I had cited articles in the architectural press and the general media about how great the economy was and how the forecast looking good. I got offers from six different banks to pick up my line of credit. So, it started out fine for a while. You know, there are some positive things about starting in a down economy. We tend to focus on the pluses and not the negatives. For instance, there are good people available. You get into some very good habits, business-wise, about how to set up and run a practice and all those things turned out to be positive things for a young firm. I would also say that my work over the years has been in the public sector. So, when there is a down economy, it's the private sector that retracts first - the developers and the banks. But there is a time lag because the funding cycles for public sector work, like colleges and universities that are public schools and municipalities, those funding cycles are six to eighteen months out. That work continues for a while even at the beginning of the recession. Our focus had been on the public sector and that was a saving grace for us starting out in 1990. All those factors played into some early success and moderate, steady growth.

Ken: Phil, did you grow up in Philadelphia?

Phil: I did. I was born and raised in Philadelphia. My parents are from there. My grandparents are from there. So that's my hometown.

Ken: From what I understand your grandfather was quite a prolific impressionist painter in the early part of the 20th century, and an activist as well, correct?

Phil: That's right. He was a noted painter and art educator during the Harlem Renaissance period. If you pick up most books on African-American art from that period, it's likely you'll see some of his work and reference to his paintings and his activities there. I remember him and certainly having art around the home we have in that part of growing up influenced my interest in the arts. My parents fed that interest and encouraged me and recognized some talent in the visual arts. And that was great.

Donna: I'm guessing growing up in Philly then, and with your grandfather there, there must have been an introduction and some time spent at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Furness building? Would you consider Furness some kind of influence? Or did you have those kinds of childhood experiences in those buildings?

Phil: Not directly. As a youngster, I was not really a serious student of the arts yet. But I remember visiting museums and visiting my grandfather's studio and kind of poking my finger in the palette of oil paints and wondering, "well why is that dried up?" Things like that, and being exposed to the visual and performing arts because that's the way my family went about things. My parents were great like that... taking us to concerts and galleries... I was very fortunate in that regard. But I didn't know anything about any architects or Julian Abele or anyone else. Paul Williams - didn't know anything about any any architects, black, white or otherwise. My parents didn't know any. And so I just kind of stumbled into it, not realizing or understanding much about it.

It just turned out it was the right move for me, and the right career. The more I learned about it and got into architecture school and just really excelled.

Ken: You were in high school just around the time I was born, in 1968, and so you were just coming into junior/senior year at that point. When you reflect on that period of your life and your experiences in the city, and you think about where we are today what comes to mind?

Phil: It's almost deja vu! I mean the mid-60s were just such a heady time. I mean there was the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement... Just think about it, I was coming of age right at that time was just so compelling and powerful. I had an afro and I just was really enamored with black culture. It was just of a very influential period of my life. Yeah, there was a lot of upheaval but the music and the art and all that was just really wonderful. On the flip side, they were busting heads in Philadelphia. Frank Rizzo was police chief. There were riots and assassinations during that period. All that converged to make this really intense coming of age for me and my siblings. The reason I say it's deja vu is that the racial tension is reminiscent, with Black Lives Matter and the political polarization that we see today... it's just very reminiscent. I mean just like bringing back memories.

Ken: I say to friends of mine all the time that if you would have told me when I was born (I was born between Dr. King's assassination and Robert Kennedy's assassination) that I would be caught up in something very similar. I would have said you're a liar and it was complete science fiction.

Phil: Yeah, this is really bizarre. Again, I'm just an optimist and I think that the times we're living in today, maybe it will wake people up because a lot of this has been there just hasn't been on the surface. If the awareness is heightened about the struggles of the African-Americans and the struggling class, in general, if we're illuminating that now by virtue of what's happening then maybe that's the positive we can take away from it. No one flipped the switch. Attitudes haven't changed. They've always been there, they're just on the surface now.

Ken: One of the things that was pretty striking for me was looking at some of your book lists. I don't know if you recall, but I saw that there's some science fiction in there. I know that you have a degree from MIT... you know, science fiction is always kind of been on the periphery for me in terms of reading but it seems pretty strong and I know that just reading your biography and seeing your son's background with Afrofuturism. How did that come about and how does that inform your thinking about design at all?

Phil: Absolutely, you've really done your homework! This is great!

Ken: I really wanted to talk to you about...

Phil: I'm so impressed! The last interview I did the woman asked me, "tell me who is Phil Freelon," and I thought to myself that she hasn't done any research. Boy, you've been digging and that's great. Yeah well, you know science fiction... I'm trying to remember why and how that all got started. I think my older brother recommended Dune to me, by Frank Herbert, you know back in the 60s and I read it. Even before then you know we would go to the movies together. He's four years older but we're very close and so that it's always been a fascination. Then I met my wife... the first day we met we talked about Dune and we talked about Star Trek and we talked about Star Wars and all these things and there was a common interest there. I think as an African-American, you want to envision a future that's better for everyone so that that's part of it.

Then I met my wife... the first day we met we talked about Dune and we talked about Star Trek and we talked about Star Wars and all these things and there was a common interest there. I think as an African-American, you want to envision a future that's better for everyone

And then just try to imagine how people would live that's the architecture piece. What is it about these different authors and their vision of the future that might be inspirational to me as a professional in designing the built environment. That's part of it. Reading about that and then the movies and TV shows are just a lot of fun. I watched an old Star Trek episode last night. You know black people are there, they're in charge, in important positions... no one's talking about race unless it's the aliens, you know?

To me that was was kind of an optimistic look into the future. Gene Roddenberry had a very progressive approach to how to depict those kinds of conflicts in the future to reflect back on where we are today to see how crazy it is. Those things have been intriguing to me about science fiction.

Donna: You mentioned, Mr. Freelon, that you were in Philly in the 60s. I lived in Philly for ten years, not too many years ago. I became a big fan of the Kenny Gamble sound during that time which, you know, you can't escape his amazing influence when you're there. And the music holds up! It's still my favorite music to listen to all the time. So I wanted to ask you about the Motown Museum edition and what you're doing there.

Phil: Well before we do that let's talk about Kenny Gamble.

Donna: OK. What are you doing for Kenny Gamble? He's a real urban activist too.

Phil: Yeah, absolutely.

Right before the recession, I think it was in 2007 or 2008, he had a request for architects to come to Philadelphia and vie for the commission to design the Rhythm and Blues Center, actually, he called it the National Center for Rhythm and Blues. His own version of the Motown Museum. We went, along with five or six other architects, and presented to him and he was blown away. He selected us and I got to know him and then the recession hit and there wasn't any money. This was to go on South Broad Street. So, I got to meet him and talk to him and it was just wonderful. The music was parallel with Motown. I love Motown also, but being from Philadelphia I'm a little bit biased to the Philly sound. I just grew up with it... The Delfonics and the O'Jays and on and on.

Donna: Love Train! The only song I cannot not dance to.

Phil: This is terrific. So Motown came around about a decade ago, with a similar process to Kenny Gamble's search for an architect. The Motown folks invited a number of people to submit qualifications and then interviewed a handful of architects. We were one of them. This was in Los Angeles. I met Berry Gordy and Smokey Robinson and others. We didn't get the project and I was distraught about that, and just sort of forgot about it. Nothing ever happened with that version of the effort. And then, when it came back around, I was called and there wasn't any formal interview process with anyone else. They just called me up in Detroit. I met was Robin Terry, who is the grand niece of Berry Gordy. Robin Terry's mother is Esther Gordy, who was Barry's sister, and when Mr. Gordy moved Motown to Los Angeles it was Esther that was the keeper of the flame and all the artifacts and gowns and records and stuff. It became sort of a mom and pop museum based right there in the old Hitsville House and so her granddaughter, Robin Terry, who's now the president and CEO, chairman of the board of the Motown Museum, has been working on a plan to renovate, add to, and build the Motown Museum. So we went out and showed what we've done in other places and talked about her vision and we continued to work on it. We're the architects now. We're in schematic design. We helped them raise the funds with the United Auto Workers and Ford Motor Company as initial donors. We met with the Motown alumni in Los Angeles and Detroit with enthusiastic support of our concept and so we're off and running.

It's a delightful project. I just can't be more thrilled. People often ask me when we talk about the Smithsonian Museum, I get this kind of snide comment about well, what's next? What else could you do now? I'm doing the Motown Museum as a matter of fact, which is pretty darn cool!

Donna: One of the articles I've read about you said that it told the story of how you approached the building committee, or the executive committee, whatever their title is, for the Motown Museum, and that you initially asked them to bring images of buildings that they love as well as some kind of artifact of Motown and what that meant and how that influenced their thoughts on Motown. Since you do so many cultural buildings I wanted to see if you could talk a little about how you draw those sort of memories and cultural identities and what's important and what people love and feel passionate about in these projects. I assume you do that with many of your clients?

Phil: We do. And with any project, especially projects rooted in culture of some sort, like libraries museums or cultural centers, it's important to figure out what are the drivers or what are the aspirations and visions of your constituents... the people or the stakeholders and whatever the institution is. So we put a lot of effort into listening. Listening aggressively. Trying to understand what it is that's at the root of those institutions and what are the drivers. And we do a lot of research on our own.

... we put a lot of effort into listening. Listening aggressively. Trying to understand what it is that's at the root of those institutions and what are the drivers

We can say, "well this is what we've seen and what we've heard" on our own. Part of the charrette process is to share those things and have a common understanding of what's important. You're not marching off into design without having those kinds of engagements that really inform the design solution.

We don't go off for a month or two and then come back and unveil some masterpiece. It's a process. It's a process that is participatory with the stakeholders and it informs what we do. So what you described in Motown, those exercises are some of the ways we get at the essence of what a particular building or location or program should be.

Donna: Can you share one from any project that's particularly moved you?

Phil: Sure sure. When we were doing the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson, one of the exercises we had was a postcard from the future. We asked people to write down what they saw and felt seven or eight years in the future when the museum was open. Know what were the emotions that they felt and what did they see you know. And so the idea was to look ahead and try and visualize the future. We were getting into science fiction a little bit here. Then we asked them to pretend they were standing next to someone because when you've been involved in the process sometimes you're too close to it.

So we wanted to imagine what other people might say wandering in for the first time and seeing it. If you were the architect or if you had been on the building committee or the user groups or the owners you're immersed in this stuff for year after year of development of ideas and planning and construction. But for someone just arriving has a totally different perspective on things and so we wanted to imagine what would a stranger to the process, or a new patron of the institution coming in, what did they say and what did they feel?

These are just some exercises that we have and then we give homework before we get there and we ask people to bring images of buildings or places that they had been impressed with or that moved them in some way. They don't have to be a museum. It could be anything. And that's the way they communicate not with words but visually through images. You can describe it with words but you know we get to see the kinds of things to do, or not to do, to avoid and to talk about what is it you like about that particular courtyard or entry sequence? Why did you show this particular gallery of this particular theater? What is it about? And try and drill down a little bit into you know the drivers for that emotional response and all these things feed in and are helpful to us as designers. At the end of the day, we want to interpret what we see and what we hear and we want to interpret that into three-dimensional form but it's just part of our process.

Ken: Phil, when I was looking at your firm's website one of the projects that struck me particularly because it was 1) it was quite beautiful and 2) I'm just curious to know if there's still hope that it will be constructed or if it is under construction was Emancipation Park in Texas.

Phil: Yes it's almost finished.

Ken: It is?! Oh, fantastic! It's a beautiful park.

Phil: Yeah, well I can send you some photographs near completion. One of our architects took some really nice shots. Yes, that's been realized and we're excited about it. Juneteenth celebration coming up this summer is going to be there. That's kind of their signature event. Before that the Director of Parks and Recreation there is having his retirement party there and he's been so pleased with being involved with it. His name is Joe Turner. I'm going there in March. He asked me to speak at his retirement celebration. Yeah, that's been a great project for us. And it involved all the things we talked about. We had a number of stakeholder meetings. We engaged the community numerous times to get feedback and buy-in and support for a community-based project like this in the Third Ward of Houston, Texas which is one of the historic black neighborhoods. Back in the 40s 50s and 60s, if you were black and you wanted to go swimming you had to come to Emancipation Park. It was the only swimming pool in the city that black folks could swim in. Of course, the segregated South is not a new story. I lived in Houston for a while so I knew people there. Early in my career, I was in Texas for two years, in Houston.

Ken: Getting to the Smithsonian project... I have just recently watched the documentary I Am Not Your Negro and I thought one of the interesting quotes to come out of that story about James Baldwin is that the story of the African-American is an American story and the story about slavery is it's an American story. You talk about the museum as being an American story. It seems to me that it's lost on people that this is a story that is purely about African-Americans when it's really an American story. Could you talk a little bit about how you were thinking about this museum and how long you had been thinking about it? And could you talk a little bit about your project manager Zena Howard, your senior principal involved in the project?

Phil: Well, you know you're absolutely right, the African-American story is what Lonnie Bunch calls the quintessential American story. It could be about the Irish people or it could be about other immigrants. Our immigration was forced, but it's what you do when you get here... the struggles and the triumphs and not just the victims and perpetrators but the successes and the resiliency. All that is part of an American story, the quintessential one. It's not just the exhibits which get into the finer grain of things but we felt that the building should begin to express those aspirations and part of the history should be conveyed through the architecture. That's a common theme in our work. Particularly the cultural work. We feel that the architectural element to be more than just a container or a wrapper around exhibits. We feel that the architecture should help to tell the story. It should be integral with the exhibitry and the artifacts, so there is a unified experience. The visitor experiences is seamless.

That's something that we talked about in pursuing the project and for me that pursuit of that work, that commission goes back about 12 or 13 years. Brad heard about the project and that it was a commission that was set up to study the possibility of a museum on the Mall in Washington and that was in 2003/2004. I began to visit D.C. and attend the commission meetings and got to know some of the commissioners there. I knew that it was a long shot and that it would take a lot of preparation and being in the right place at the right time. So that idea of it goes way-way back for me. And you know talking about it for years and then preparing and putting together an alliance of architects that put us in a good position to compete for the work.

Ken: I only heard about Paul Revere Williams about this time a year ago and I was looking at his work and what blew me away was the diversity of the work. It was modern, it had you know old Hollywood. It had a stylistic range that I think rivals many contemporaries today that you wouldn't expect to be that varied. When did you first come to know about Paul's work and how did you get involved in the process to get the AIA to award and the gold medal posthumously.

Phil: As a young architecture student I was curious to know who else is out there has been doing this and I was looking for my heroes. The history of architecture courses in the curricula around the country don't talk about anything but the Western and American architects, right, nothing about African architects... there might be now but not much I can guarantee you that. So the focus is on a certain narrow slice of what someone thinks is excellence or is worth note. People like Julian Abele, if you don't know who he is you should look him up, Philadelphia architect and a contemporary of Paul Williams.

Anyway, back to your question, I wanted to know about these things and so I found out about Paul Williams and probably every black architect you talk to will tell you they've heard of Paul Williams. Every white architect you ask doesn't know. So it's a matter of seeking out your own heroes and wanting to find out if there is a path for me in this profession. And so I found out about Paul Williams somewhere along the way during my student days. I never met him but I knew about him.

I guess a few years ago a conversation started with the National Organization of Minority Architects, which I'm a member, it's mostly African-American architects but also includes other underrepresented groups. There was a notion that Paul Williams needs to be recognized. We all knew that he was this incredible architect and that there wasn't any notion of this beyond I guess the black community of Architects which is very small, you know 2% of the architects in this country are African-American. There's a process that the AIA has as a whole division of that organization that focuses on awards that be the person of the year or AIA gold medal or National Design Awards for buildings.

Part of that process is nominations and letters to get you least considered for the AIA gold medal. There are some things that have to happen, so we organized that and got letters from people like Frank Gehry and Denise Scott Brown to former AIA gold medal winners who wrote on behalf of Paul Williams to be considered for this, along with a bunch of black architects, as you can imagine. So we were able to get in the position to be selected as one of the finalists. This year there were three finalists and Paul Williams was one of them and I was chosen or asked to be the person to present our case to the board of the American Institute of Architects and I prepared the PowerPoint show we had 12 minutes. So that was tough. I presented, and I was there with Robert A.M. Stern who represents Zaha Hadid and then Moshe Safdie presented Richard Rodgers and I presented Paul Williams. We prevailed so I'm very proud of that and happy that Mr. Williams is getting the recognition that he so much deserved, albeit late. Long overdue.

Ken: Recently the AIA has gone through some Sturm and Drang around the issues regarding the knee-jerk support for the current president and then is now hitting the backside of a conservative backlash on the more conservative end of the profession. When you think about the profession as a whole are you comforted by the direction we're heading or are you concerned? What's your sense of us as a professional organization? I know we have a lot to do. I think we're horribly underserved by our leadership in terms of representation and so I wonder what your thoughts were around that.

Architects have the skillset and the position in our society to be more impactful in some of these entrenched social problems that we see, whether it's housing or equity issues in terms of resources, energy conservation, sustainability...

Phil: Well, I think that architects could do more in general and therefore, by extension, I'll say that our service organization, our professional organization, could certainly do more. Architects have the skillset and the position in our society to be more impactful in some of these entrenched social problems that we see, whether it's housing or equity issues in terms of resources, energy conservation, sustainability... yet sometimes we're just more focused on giving awards for pretty buildings that are designed for people can afford the very most expensive materials and sites and things. So, it's disappointing that we as a profession haven't done more. If you think about the lack of diversity... if the room with all the people that make these decisions... if there was more diversity in the room someone might have said, "hey, wait a minute, let's think about where what going to say after the election." For all the reasons that diversity is the right thing to do, having different viewpoints in the room is helpful, especially from a design perspective but in something simple like how we're going to respond to the current political situation or how we respond or if we do what's appropriate and what's not–whether it's from the conservative or liberal perspective. You've got to have more than just a couple guys in the room that all went to the same schools and all look the same. You know this is ridiculous.

Phil: I've been pounding on the AIA. We all have for a long time. I just did a panel discussion in New York last month about the lack of diversity in the profession. I was at the Architecture Center which is the headquarters of the New York AIA.

We talked about this. People have been lamenting that the AIA is not diverse and you know we wring our hands and we fret about it and, you know, decade after decade goes by and it's still the same.

Donna: So do you have advice for younger architects coming up for how to keep pounding on that problem that you've been working on?

Phil: Yeah, it's a multifaceted issue and problem because, first of all, architecture is kind of a small profession, to begin with. There aren't many of us of any color you know. I think there are 110,000 architects in the country, that's it. By comparison, I think there's something like 800,000 physicians and well over a million attorneys. So it's a small profession and then that small profession we have a very tiny slice - 2%. So the key is bringing up that percentage and making the profession more diverse and that sounds easier than it is. If you think about all the obstacles to becoming an architect it's just a miracle that those of us can get through it. First of all, you have to know exactly what you want to do out of high school. Why? Because the architecture curriculum in these accredited schools architecture begins on day one and many of the schools have higher entrance requirements for those programs or design programs than for the general university. How many kids know at age 17 or 16, 17, 18 that this is what I want to do for my career? I was fortunate, I knew, but it's not the average person. If you have the resources you can go and do 4 years and become a history major and then go to Harvard get your masters of architecture. Not everybody can afford to do that and have the resources and the flexibility to do it. So that's a barrier. Just getting in, knowing about the profession, getting accepted to an architecture school in an accredited program. Is anybody on the line an architect?

Donna: Yes. Ken and I both are.

Phil: OK. So you know what it's like to get through architecture school. The late nights and the professors that smash your models and discourage you... so just imagine getting to architecture school and there's nobody else around that looks like you, no professors to mentor you. That's why it's a miracle so many of us have gotten through because it's hard for anybody. What if you came from a high school that was substandard and you're trying to catch up on the required math and science courses because you're from the inner city in the schools were crappy, and in the meantime, you're being asked to stay up all night build these models and stuff.

Phil: So I'm just giving you a sense of why it's not more diverse - awareness, the difficulty of the curriculum, you get out and you're not making any money because you've got to take an exam... before that you've got to qualify and work for nothing for a few years to have the privilege of taking this two-three day exam... and then your licensed then what do you have? You still earn a pittance. This is crazy you know, and unless you're totally dedicated it's hard to get through. Those of us who are African-Americans that come through, I mentioned the 2%, well guess what the fellowship in the eye is 4% African-American. Why? Because if you make it through that far you are already better than most of the people around you. And you know it's just you're operating at a very high level.

Ken: You've had a 30+ year career and you've recently been diagnosed with ALS. How has your career as an architect impacted you as you move forward with the disease?

Phil: Well, that diagnosis impacts everything including my personal and professional life and everything. That's a really short correct answer. I've always been sensitive to issues of accessibility, but when you're you're hitting those barriers yourself it brings a different kind of reality to it. There's a higher level of awareness about universal design and accessibility... not just putting a ramp over there so somebody can get up but how does someone feel a part of the normal experience of the building without being, "yeah you can get in but you got to go around the corner to do it."

It's had an impact on my thinking about design. I think it underscores something that I've always believed in and there has always been committed to and that's equality and accessibility. It's not a change, but a sort of the intensification of the commitment that I've always had. Now, because I'm doing meaningful work that's fun and exciting and invigorating, I want to continue to do that rather than just throw my hands in the air and say, "well and have a few years let me just check out." I'm continuing to work full time, continuing to travel, and that gives me energy. It's been a continuum of my work and has been a plus.

My clients know about my situation and it's not impacting my work, yet, it might, it will over time. And probably sooner than later I will curtail some of the travel and my time in the office. With this condition, in some cases, affects a person's ability to speak. That's not happening, yet. For me, it's starting more with my legs and mobility in the lower half of my body. For that, I'm grateful because if I weren't able to communicate it would be more difficult to do my work if I wasn't able to speak. I'm grateful for small things like that. I have the support of my family. My children and grandchildren all around me. I just want to continue to have a positive impact on the communities where I work. It gives me pleasure and satisfaction to still, 30 years in the profession, to do this. I'm fortunate to still feel passionate about my work and excited every morning when I get up to come in and do it.

Ken: I notice on your reading list A Brief History of Time. Have you had the opportunity to reach out to Professor Hawking?

Phil: No, I have not. I did that list years ago!

Ken: I know, I know I saw the list and I was thinking...

Phil: It's kind of ironic, but no, I haven't. I mean he's an international icon, superstar, and he wouldn't know who I was or why I was calling.

Ken: You're a superstar!

Phil: He's made some choices about how he deals with the disease that I'm not sure I would want to do. You know, quality of life is important to me so I'm not at the point where I've got to decide do I want to have a machine breathe for me, do I want to be fed with a tube and move nothing but my eyes to try to communicate. In some ways, I don't want to know any more about that than I need to until the time comes. That is interesting, looking back on it, he's the only person I knew of with ALS, aside from Lou Gehrig, and here we are talking about it six, seven, eight years after I made that list.

Ken: Will you attend the convention this year in Orlando?

Phil: Yes, I'll be there.

Ken: Can I meet you and shake your hand?

Phil: Sure, of course, I'd be happy to do that. Let's stay in touch so we can do that.

Ken: I want to finish up by asking the two questions that we typically ask are our guests. Who are you reading these days and what are you listening to.

Phil: Oh great question. Well, I like Malcolm Caldwell, and I've read his books, and so those are kind of recent. I also read all of Dan Brown's books you know. Those are fun. And of, course some, some science fiction mixed in there. Octavia Butler is tremendous and she also happens to be an African-American woman. What am I listening to? We've been into Brazilian music in recent years, not just the bossa nova but deeper into it, the Afro-Cuban influence and Salvador Bahia and the African diaspora through Brazil and the music that comes out of that. Milton Nascimento, Djavan, folks like that. Being married to a jazz musician, six-time Grammy nominee, music's in the house all the time, so we enjoy that.

Donna: It's been a pleasure talking to you. It's been an honor. Thank you, Phil.

Phil: Well, thank you.

Paul Petrunia is the founder and director of Archinect, a (mostly) online publication/resource founded in 1997 to establish a more connected community of architects, students, designers and fans of the designed environment. Outside of managing his growing team of writers, editors, designers and ...

2021-present: Senior Owners Representative at IFF. We are a Midwest CDFI nonprofit that offers real estate and facilities services to non-profit organizations. I work in the Indianapolis office. 2017-2021: Architect at Rowland Design in Indianapolis. 2012-2017: Campus Architect at the ...

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

1 Comment

this was interesting, thanks for posting the transcript.

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.