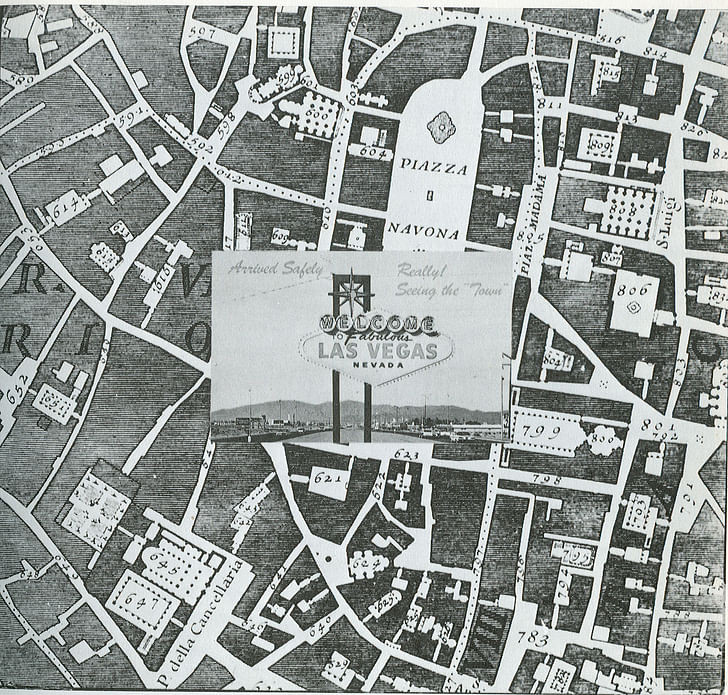

Nearly fifty years ago, Denise Scott Brown, her husband Robert Venturi, and Steven Izenour brought nine architecture students, two planning students, and two graphic design students to Las Vegas. There they studied the famous, if often derided, Las Vegas Strip, discovering a wealth of meaning in its bright signage. Their findings, published four years later in 1972, became one of the seminal texts of architectural theory and influenced an entire generation of practitioners and thinkers.

“Learning from the existing landscape,” Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour begin, “is a way of being revolutionary for an architect.” Perhaps more than anything else, the research methods pioneered in Learning from Las Vegas have changed the way architects practice and study, recasting quotidian landscapes as objects to be analyzed rather than ignored or denigrated. “Withholding judgement may be used as a tool to make later judgements more sensitive,” they write. “This is a way of learning from everything.”

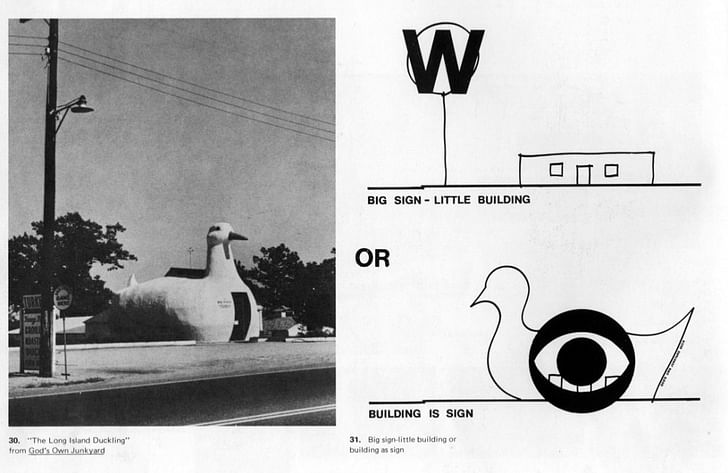

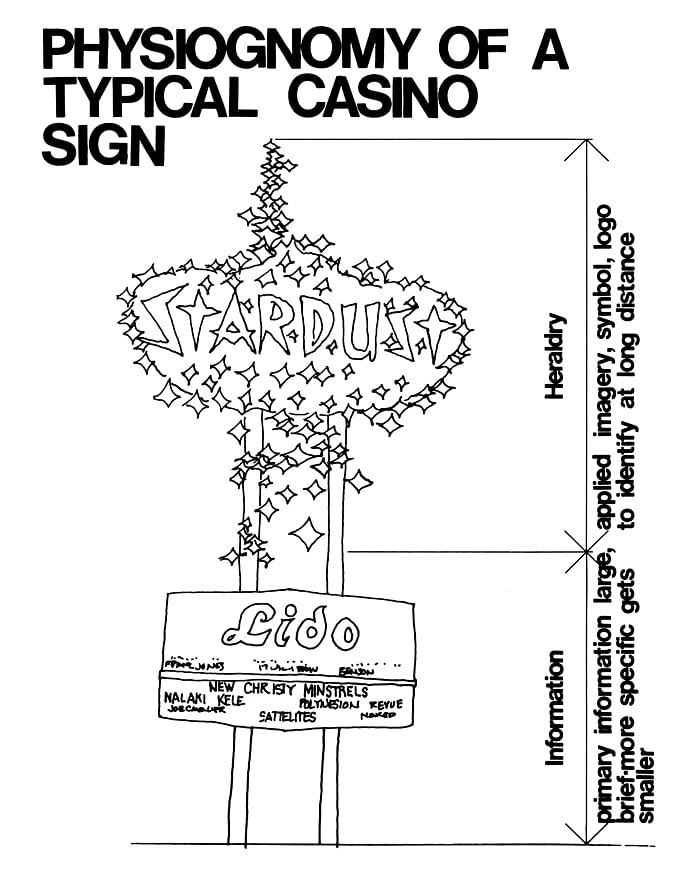

In Learning from Las Vegas, architecture appears as “decorated shed” or “duck”. The former relies on imagery and signage to convey its program. The latter expresses its program and meaning in its form. If much of the then-dominant “late Modernism” eschewed ornament, prior architectures acted more as “ducks”. With the publication of the book, Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour helped usher in a return to ornament and symbolism in architecture, as well as a new focus on the architecture of the everyday.Learning from the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary for an architect.

In the process, the book divided the architecture community into two camps: “the Whites”, including Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves, who wrote against the book; and “the Greys,” including Robert Stern, Charles Moore, and Allan Greenberg, who defended it. Today, the influence of Learning from Las Vegas can be read in the work of many of the most significant contemporary architects, from Rem Koolhaas to Diller, Scofidio and Renfro.

I talked with Denise Scott Brown about the background to the book, as well as her thoughts about its continuing influence and relevance. The results are published in three edited parts, beginning with this one, which details her early biography.

What originally brought you to Las Vegas?

My whole life, you could say. Members of my family left Eastern Europe for Africa in the late 19th century. We were ethnics in the wilderness. My mother's parents, living in Zambia and Zimbabwe, started in mud huts, hunting for food, and cooking over outdoor fires. My mother grew up there and spoke some IsiNdebele. I learned a little from her, and some veld lore.

In my teens I too camped in the wilderness, but to excavate for early human fossils and Stone Age implements. As an architecture student, I studied South African landscapes and housing and, gaining urban insight, I grew interested in the melding of African folk- and white industrial-cultures. And when I saw the outrage of scholars and purists at such divergences from tradition, I gained a taste for studying the shocking.

These impurities were created in Johannesburg's mining outskirts where rural migrants could pick up discards around them to make toys, tools, and parts for their houses, and bend their traditional decorations to respond to the foreign customs and patterns they observed.when I saw the outrage of scholars and purists at such divergences from tradition, I gained a taste for studying the shocking So beadwork used to cover gourds, or to send necklaces, color-coded for love messages, now covered soda bottles. And on the painted wall decorations of Mapoch houses, renditions of bicycles and nearby suburban houses began to appear.

I was involved from childhood in such mixings of cultures in our multicultural country. But from the 1930s refugees of various nationalities, fleeing Hitler were added. Doctors, lawyers and engineers who weren't licensed and couldn’t practice, became lab assistants and music teachers. Amazing people clustered around our education systems, so I had refugee teachers in grade school, high school and university.

Artists among them were latter-day Impressionists who interpreted rural Africans as the "noble savage," a la Gauguin and the Romantic movement. I love their paintings, but I love African depictions of Western life even more.

And so my views of Las Vegas were initiated. There was also my discomfort with English expats who, shielding all but a small corner of our beautiful veld from view, said "that could be a little bit of Surrey!" Why did it have to look like Surrey to be beautiful, I asked, and affirmed my belief that what's considered ugly must nevertheless be examined and understood.

In England in 1953, Brutalists were saying something similar about American pop culture. There were Pop artists in England in the 1940s and Alison and Peter Smithson liked them in the early 1950s and counted one of them, Eduardo Paolozzi, as their colleague.

Another skein was my mother, being in architecture school in the late 1920s, had friends who were young rebel Modernists, disciples of Le Corbusier. When my parents decided to build a house in Johannesburg they hired one of the group, Norman Hansen, who designed us a beautiful ‘International Style’ house—as it would now be called. But they refused to regard what they were doing as a style, and hated that name. For them our house would have been ‘early modern’ or just ‘modern’.

by the 1950s I was surveying the shocking things of popular culture, advertising and communicationI remember seeing its plans, blueprints, at the age of two, and it was central to my childhood. But I loved too the philosophy of Modernism as taught me by my mother at five, in situ and via copious drawings. She and we drew all the time and my loyalty to early Modernism starts with her. So does my swivel-tilted head and looking-and-learning stance.

Le Corbusier's ‘eyes that will not see’ were part of it too, but Corbu's unseen things were granaries, silos, industrial buildings, and the tops of ships, while ours are the everyday landscape, commercial and residential, and The Strip. And the eyes we turn toward them, I call "wayward".

As a continuing industrial romantic—one now nostalgic and, after Vietnam, sadder and wiser about technology—I continued to photograph pylons, bridges, pumps, freeways, and juxtapositions of these. But by the 1950s I was surveying, as well, the shocking things of popular culture, advertising and communication.

The Smithsons loved them too but later cast them out and following Miesian dicta on form and structure, turned New Brutalism into neo-structuralism. But Mies's structures were made to look rather than be structural and, in the end, we must admit that he was a Modernist for stylistic reasons. And so were the Smithsons.

Their urban critique however, was not formalist. It stressed street life and was based on studies by English sociologists on deprivations of the poor in post war London and how their supportive social networks were broken by the disruption of their neighborhoods and their "decanting" to Greenbelt cities. There, inserted into a middle class life, neighbors could no longer talk over garden walls, or children play hopscotch in the streets. Such things had supported family and social life. And so had the walking environment in neighborhoods where men might travel to industrial work but mothers and small children could walk to satisfy most needs, including those of work. Factory jobs for women near their homes existed in what economists called byproduct industries. These employed the wives of workers in heavy industry, to sew shirt wastes or shoe uppers, or operate ribbon mills in small factories near home. And children played where mothers could see them from their kitchens.

In South Africa, I saw how, despite apartheid, Africans got together in our zoo and its connected park, open by deed to all races. And downtown there were smaller groups. I remember seeing what seemed to be traditional pebble-throwing games, perhaps 1,000 years old, taking place at lunch hour on a Johannesburg sidewalk.

Then I came to America and studied city planning—wasn’t that what Le Corbusier did? In England and Europe architects felt this was where the greatest opportunity lay and really talented designers should go. In London I heard a socialist architect say ‘I go where the money is: to government’. They were the only builders then. So we all intended to work for cities as planners and architects both.my spaces are used—because in planning them I considered what I was taught by social planners

I was inspired by the visionary cities of early Modernists, Le Corbusier, Sant'Elia, Garnier, Soroya y Mata, Hilbersheimer and the MARS Group, but at Penn, I found them in staid, old textbooks, and the interesting ideas were happening around social scientists and social planners. Our young sociology professor, Herbert Gans, moved while teaching us to Levittown to be a participant observer in its initiation as a community. His teachers were upset. They were studying silk-stocking districts, gold coasts, and how the rich lived at high densities. And he was moving to Levittown! It wasn't even social housing. But I had seen what was really working in low-income housing in Johannesburg and it looked like Levittown. I saw the parallels and began approaching suburbia more clinically.

The social planners admonished us: you architects are so arrogant about what people want. But people stay away in droves from your spaces. You can’t say you're designing a public space. Only public use can make it public, and probably they won’t use yours because you haven't thought hard enough about what they want and need. You give them something you find beautiful, but what’s it worth if they can’t use it?

I was their friend and sympathizer, I firmly straddled both camps. But I was the only architect around and I grew tired of being called "you architects!"—especially as I had agreed that you can’t force people to meet but you can make meeting easier by putting places along their travelled paths and particularly where these cross, then making them useful and comfortable. I’ve done this, and I’m proud that my spaces are used—because in planning them I considered what I was taught by social planners.

To architects I say, observe a lot; read outside architecture on urbanism. To study Las Vegas we learned from many sources, guided by Herbert Gans, Paul Davidoff, William Wheaton, Robert Mitchell, Walter Izard, and David Crane, people architects should know.

Bob Venturi was the only member of the architecture faculty who sympathized with my attempts to straddle architecture and planning responsibly and also imaginatively. Bob was a studio critic when I arrived at Penn in 1958. We met—not as some people think in 1967, but in 1960 when I joined the faculty.

Although we grew up worlds apart, we found we had surprisingly much in common, in our architectural stances, swivel-tilted heads out tilt toward Mannerism, and experiences in Italy. [Our ideas] have been picked up in universities all over but not yet very well—they don’t know the half of what we didWe started to talk about architecture in 1960, and to collaborate as colleagues when in 1961 we began to teach consecutive semesters of the theories course for architects. The aims of the school for these courses were complex and each involved a series of lectures supported by seminars and work topics intended to help relate the lectures to studio projects in design—that is, to relate theory to design.

From that time we worked together—first as teachers, communicating ideas and subject matter, tying coursework to studio, architecture to planning, and the subject matter that interested [us], to the students' work and ours as designers. In 1964 I ran the work topics, seminars and term papers for both courses. Bob's lectures introduced new ways for architects to approach history as designers and formed the basis for Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. They adapted planning methods of seminars and work topics, introduced ideas on architectural research for design that we extended in the Learning from Las Vegas studio.

These have been picked up in universities all over but not yet very well—they don’t know the half of what we did.

What do you mean by that?

I'll tell you in the next installment.

This article is part of Archinect's theme for September, Learning. For more on the ins-and-outs of architectural pedagogy, click here.

Stay tuned for more installments of our conversation with Denise Scott Brown!

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Venturi's C&C was a serious study of historical styles in relation to modernism, but Learning from LV is flawed by all of this duck stuff... ignoring that most of Las Vegas is still made up of buildings that look like buildings. It's already at exaggerated self-parody before leaving the door, just like Gropius over exaggerated the machine and process over built form, in order to sell his ideas to the world.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.