Consciously or otherwise, social context determines design. Architecture, in turn, is capable of not only representing political ideals but also of reinforcing or shaping them—for example, through fostering forms of collective living or through breaking down gendered behavioral norms. The following projects may not be well-remembered, but they represent ambitious attempts to address or challenge the status quo through the built environment.

1. Narkomfin by Moisei Ginzburg and Ignaty Milinis

While Narkomfin House’s current state of decay doesn’t evoke a sense of historical significance, the building embodies the grand urban and ideological changes Moscow was going through during the early 20th century and represents a political agenda imposed through its unprecedented structure. Designed by the Soviet constructivist Moisei Ginzburg, the complex was built in 1932 as a part of efforts to house Moscow’s increasing population.

Narkomfin comprises an apartment block and a separate building, connected by a bridge, that contained communal facilities such as a kitchen, dining room, and laundry. Through sharing amenities such as a gym, roof garden and library, residents were expected to embody socialist beliefs in their daily lives. The complex also sought to liberate women from some of the burdens of housework—through a communal kitchen, dining room, and childcare center, female residents would have more time to be productive members of the workforce.

Ginzburg’s project served as one of the first prototypes for communal mass-housing and a unique social experiment. Shortly after Stalin’s ascendance to power, and the subsequent changes that came about from his rise, the building started deteriorating. Nevertheless, it continues to inspire contemplation of architecture’s capacity to challenge established socio-ideological norms.

2. The Barbican Estate by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

Similar to the other projects on this list, the Barbican Estate in London was built during a time of sociopolitical distress. After the Second World War, London’s rapid industrialization lead to a population boom that created a demand for mass-housing solutions. Chamberlin, Powell and Bon’s project acted in accordance with the Abercrombie 1944 plan for urban development, which called for reducing traffic, creating mixed use open spaces, and establishing new dispersed knots of industry.

One of the architects’ main intentions was to prioritize pedestrian movement. A series of pathways and podiums were elevated above the road, in the process creating expansive communal areas. Alongside the residential facilities, the Barbican Estate included a concert hall, a theater, a shopping mall, and underground parking. With its monumental scale and rough exterior contrasting its lush gardens and lakes, the center is something of a combination of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City and Brutalist fantasy.

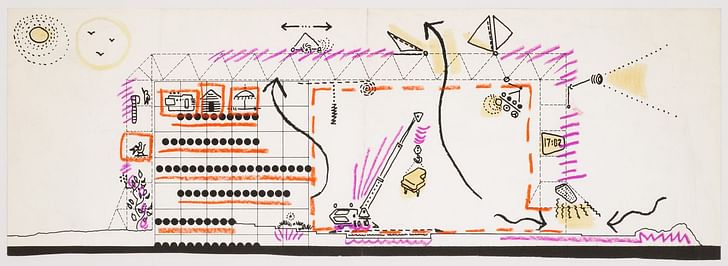

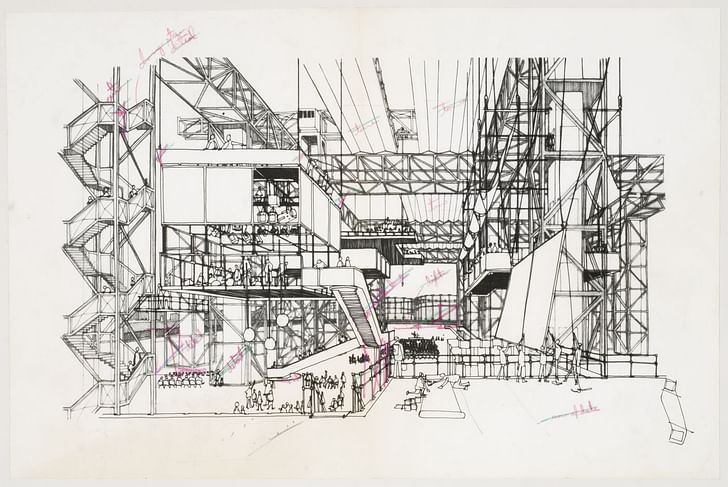

3. Fun Palace by Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price

Even though Fun Palace is often mistaken as a sole creation of Cedric Price, its conceptual framework was actually developed by a woman (surprise-surprise!) named Joan Littlewood, a prominent avant-garde theater producer.

Littlewood sought to create an unprecedented theatrical environment in which the passive subjects of mass culture would awaken to a new consciousness. That dynamic and transcendental space of cultural mixing and self-discovery was to be materialized through a framework of mobile structures that challenged the conventional definition of a building at the time while also promoting active engagement from participants.

Cedric Price developed a scheme that would allow for flexibility in the space; rooms could be altered in size, shape, accessibility and lighting.

The Fun Palace was to be a manifestation of continual change—a space in time, rather than objects in a room. It was also largely a political statement on the state of postwar England, whose population was suffering from a wave of unemployment at that time. While the Fun Palace was never built, Littlewood and Price’s ideas of flexible space and user participation greatly contributed to and influenced the design of buildings like the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

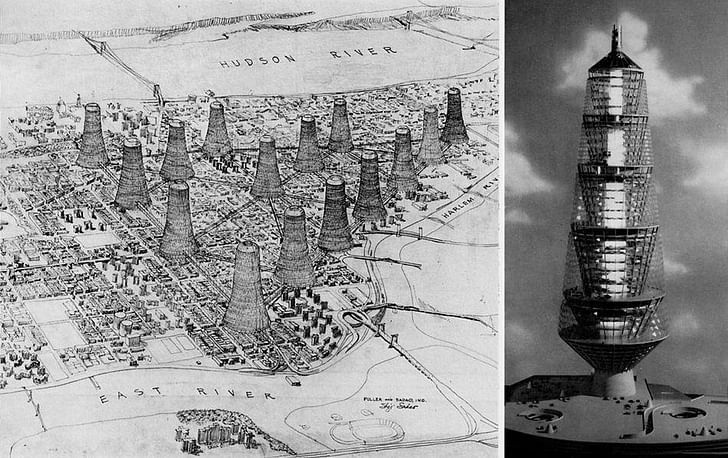

4. Skyrise for Harlem by June Jordan and Buckminster Fuller

Like with the Fun Palace, this project is usually credited solely to a man—Buckminster Fuller—but a woman was crucially evolved in its developed: June Jordan, a poet, social-justice activist, educator, and Caribbean-American advocate who dedicated her life to improving the living conditions of underserved communities. In 1965 she collaborated with Fuller on Skyrise for Harlem, a radical project meant to address Harlem’s general disenfranchisement and to “salvage” a quarter of million lives by changing the environment. The project stemmed from a deep belief in the importance of the environment’s impact on an individual or community.

Inspired by Fuller’s fascination with New York’s “vertical urbanism” and technologies of mass production, the design featured elevated conical towers supported by 100-level masts through which suspended bridges cut, creating a connecting road. In addition, an expanse of green public space played a crucial role in the project’s development. New schools, shopping areas, and playgrounds were meant to be low-cost, aesthetically-pleasing and serve as catalysts for the area’s revitalization. The project's unique eco-social approach to urban planning has often been mimicked but never fully realized.

5. Maison Médical by Lucien Kroll

Its quirky appearance might disguise its radicality, but don’t let Maison Médical’s looks trick you. Lucien Kroll’s dormitory for a medical faculty in Leuven, Belgium has been referred to as an “icon of democratic architecture.”

In fact, it is one of the first examples of so-called ‘participatory architecture’. Rooted in the belief that architecture should be freed from the designers exclusive control, participatory architecture leaves the creative process up to its future users. Through intense cooperation with students and other future residents, Maison Médical grew into a customized mix of wood, aluminum, window frames and doors. Each stage of the design was worked out with its future inhabitants—a design process both complex and radical—and took sixteen years to complete.

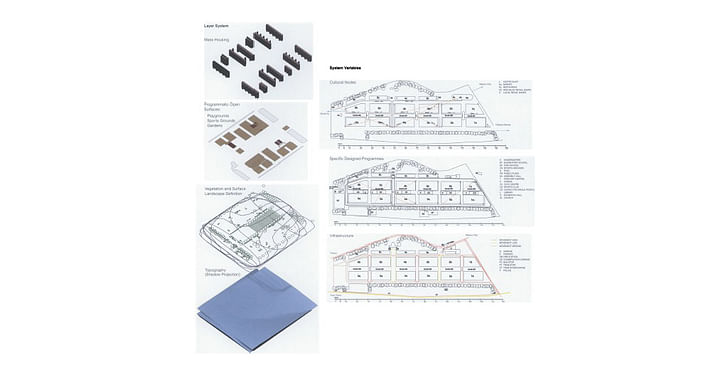

6. Proposal for Colonia Obrera in Lomas de Becerra by Hannes Meyer

Hannes Meyer was one of the most influential and underappreciated directors of the Bauhaus School of Architecture (1928-30). A radical functionalist, he believed that architecture’s main role was organizational. His approach to design embodied the original ethos of the Bauhaus: to create functional and affordable design. While Le Corbusier largely earned his fame through the aesthetization of that same idea and Mies van Der Rohe capitalized on making it ‘luxurious’, Meyer focused on the creation of socially beneficial products that largely remain unknown today.

Meyer’s 1942 proposal for Colonia Obrera in Lomas de Becerra, Mexico D.F., a 7.2 hectare development for an entirely new community, has been only minimally publicized, but it well-represents of Meyer’s work both methodically and culturally. The plan is not as rigid and typical as it might appear. In fact, it provides maximum consideration for future use, adaptable to three different organizational systems (vertical, horizontal, mixed). Meyer used scientific diagrams, charts, and formulas in order to predict future development, use, and traffic flow. The Colonia Obrera proposal serves as one of the most sophisticated and intriguing tests of an approach to architecture marked by the interpretation of space in terms of time and program.

In the architect's words, “The fundamental goal of the design was to promote social cohesion by integrating the housing program into a series of diverse events. Thus planning becomes a formal device to represent the interlocking of social and cultural spatial configurations.”

A designer & writer based in Los Angeles anastasiatokmakova.comyouthartsclub.com

1 Comment

Although I admit that I wasn't familiar with the project, I wonder whether something that is described as an "icon of...x" really be considered a "forgotten project"?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.