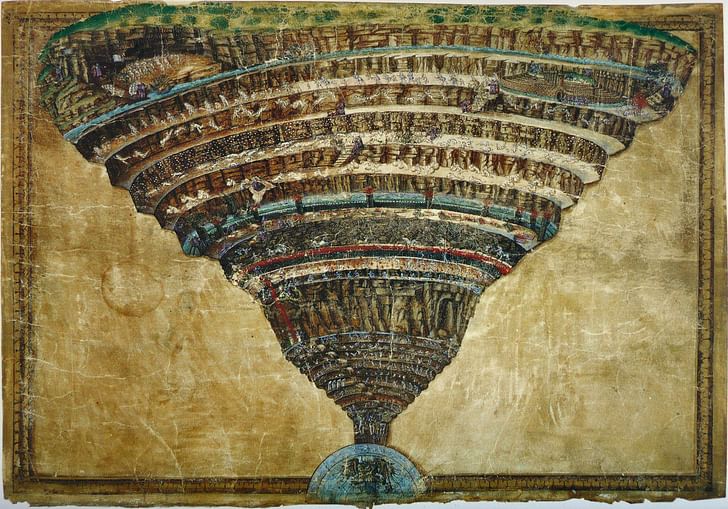

Throughout human history, every civilization has created its own cosmology, narrating and building a vision of the world, the universe, and of life and death. Each cosmology coincided with a method of shaping the human environment through architecture, and, within these realities, various cultures and forms of social organization of different degrees of completeness and complexity were born. This makes it possible to comprehend how society and social customs are continuously reimagined and actualized.

From an anthropological point of view, cosmology can be defined as a complex series of reflections and thought-systems capable of formulating visions of the world that attempt to explain and encapsulate the diversity of the phenomena that compose reality. The goal is to give order to complexity by searching for patterns in anomaly and randomness. One of the most ancient cosmologies can be found in Babylonian society, which places the Earth at the center of the universe, floating on an ocean with a cavity where the dead dwell.

While in the past different cosmologies could be found in different corners of our planet, today it appears as if all of humanity tends to share a single global version, which, although having small variations in different iterations, cannot be untied from the central vision of a world codified, interpreted and explained by our technological powers and scientific prowess. Nonetheless, if we consider that 800 years ago our species accepted Dante's vision of reality, what prevents us from building a different one today? Cosmologies are visions that constantly change, evolve and overlap, thus defining their relationship with the habitat in which they develop. Their genesis is, and has been, present as a constant in the evolution of cities.

1. Punk, Jubilee and Derek Jarman's Prospect Cottage.

In recent years the acronym DIY (Do It Yourself) has come back in vogue, especially in the areas of design, with a strong rhetoric about horizontal processes and open design. If we go back to its origins, we discover that it is a slogan invented by punk culture, where the cry “Do It Yourself!” represented a response and a real form of resistance to the decline of the "The Glorious Thirty" (1945-1975)—the years of prosperity that followed the end of the Second World War. This movement was born in 1975, the year that simultaneously marks the end of the Glorious Thirty and the beginning of a more complex period of British politics represented by the figure of Margaret Thatcher.

The term ‘punk’, which means "low-quality, two-bit", expresses the rejection of an apparently perfect and glossy world by confronting it with an ugly and violent culture of randomness and improvisation. In A Journey into the Detailed Punk Subculture: Punk Outreach in Public Libraries by April Errickson, the author places the responsibility for the birth of punk on the complex recession that Britain faced in the mid-70s. “From this recession came upheaval in the relatively stable lives of the British. This upheaval was particularly stressful to the young who saw their working class parents go from having steady jobs to having none." [1] Errickson quotes Jon Savage who, in his England's Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock and Beyond recounts how “one only had to look at the decaying inner cities to realize that poverty and inequality, far from being eradicated, were visible as never before." [2] In fact, according to Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, punk "has made its kingdom on the sidewalk." [3]

“The punk movement grew out of this drab and dark environment ready to challenge the status quo and show their contempt for government, society and tradition,” writes Errickson. “Punk was the natural progression of things. Punk’s main philosophy centered around the idea of shock value accentuated by anti-establishment ideals. Punks were contemptuous of the society around them and attempted to create a more ideal and honest environment that was not hooked in the status quo.” [4]

In the underground cult film Jubilee, director Derek Jarman describes a strong radicalization of the cityscape caused by the punk rock movement. The film presents a dystopian future of the city, which is given life not by a punk movement, but by what might be called a proper punk urbanity. The entire film was shot in six weeks with a budget of merely £200,000 and uses the city of London as its set, without the aid of additional scenography.

Throughout the film, it becomes obvious that the brutal urban environment of the film was a reality in the London of punks. In an article published in 2007 in The Guardian, Stuart Jeffries describes how all the film’s outdoor scenes were filmed between Butler's Wharf and Shad Thames before their subsequent gentrification. Only about twenty-five years later, Shad Thames was the location of the first Bridget Jones film where “Colin Firth and Hugh Grant have genteel fisticuffs outside a yuppie restaurant,” while, for Jarman, “those then-derelict wharf buildings were perfect settings for his desolate vision of England.” [5]

Henry Rollins, of the punk band Black Flag, recognizes the effects of modern design on urban life, explicitly stating in a conversation with Linda Bennet for Archininja that the modernist city, through "manipulation, control and agenda," had produced a society which “conforms to the structure of the city." [6] This precisely highlights the consequential link between urban planning, urban decay, and the emergence of subcultures.

scraps take on a new life by transforming into new messages and ways of communicating

In the late eighties and the early nineties, Jarman, who was not a punk but perhaps expressed some ideological aspects of the movement, dedicated his efforts to Prospect Cottage, a garden he managed on the headland of Dungeness in Kent. The place recalls a micro DIY Eden with a punk twist. In its formulation, Jarman used only scraps—plants grown spontaneously among the fishermen's houses—intertwined with gravel sourced at the beaches nearby. In developing the garden, Jarman’s desire to not simply exploit the land at his disposal becomes evident; the focus was to add value to what exists and give it new life by utilizing discarded metal sheets, stones and wood washed by the sea, creating a sculptural park inbetween the local vegetation.

Jarman's cottage could be described as a manifestation of his personal cosmology, which has many ties with what developed within punk culture, where the self-production of discs, merchandising and especially free fanzines allowed its proponents to be untied from the logic of the regular world and produce content at will, outside of mainstream culture. A clear parallel can be drawn between Jarman’s garden and collages used in punk fanzines or album covers, which represented very unique compositions and methods of implementation, using media clippings sourced from the detritus of mainstream culture as the scraps of the urban waste where punk comes to life. These scraps take on a new life by transforming into new messages and ways of communicating, and by building new cultural languages and architectures.

2. From the Violent Planning of Robert Moses to the Block Party

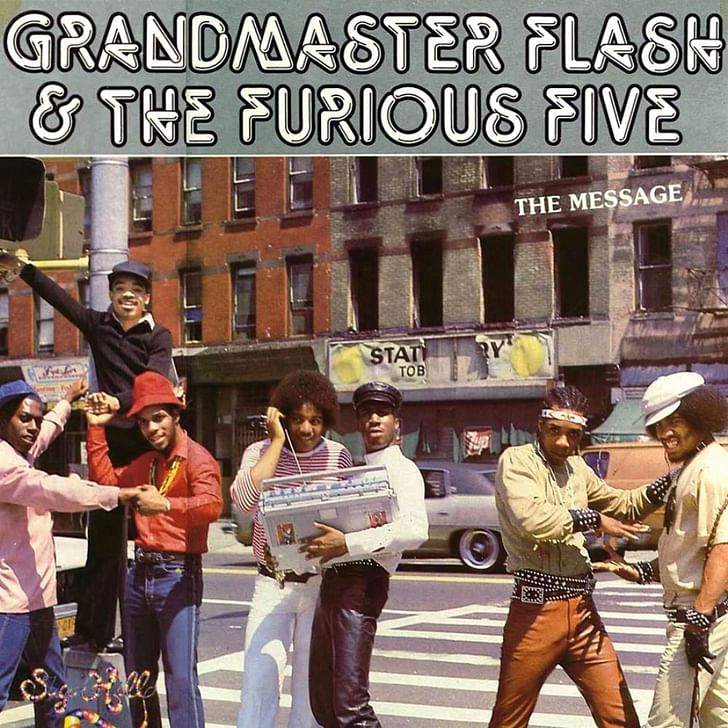

On July 1, 1982, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five released “The Message”, a cornerstone of hip hop culture referred to by scholars as the first song of ‘Conscious Rap’, a genre that focuses on providing positive visions to a young urban audience. Today, this genre is almost entirely dissolved and survives only in the fringes of more underground music scenes. In the lyrics of “The Message”, Melle Mel and the other members of the Furious Five paint a clear picture of the urban environment that gave birth to hip hop: the Bronx.

“It's like a jungle sometimes

It makes me wonder how I keep from goin' under

Broken glass everywhere

People pissin' on the stairs, you know they just don't care

I can't take the smell, can't take the noise

Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice

Rats in the front room, roaches in the back

Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat

I tried to get away but I couldn't get far

'Cause a man with a tow truck repossessed my car

Don't push me 'cause I'm close to the edge

I'm trying not to lose my head|

It's like a jungle sometimes

It makes me wonder how I keep from goin' under” [7]

The urban context described in “The Message” is the result of an infamous project by the master planner Robert Moses. In Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, Jeff Chang traces the birth of hip hop to the Cross Bronx Expressway, lobbied for by Moses and built between 1948 and 1972, which was made with the objective of creating a fast route between New Jersey and Connecticut. The Expressway could have passed through Manhattan but, due to the high price of land and the more affluent and influential social classes that resided on the island, this was not allowed.

The construction of the freeway resulted in the destruction of numerous ethnic neighborhoods, subsequently displacing the poorest sections of African American and Latino communities in the South Bronx and in Brooklyn. According to Chang, hip hop was not born as a political movement and had no manifesto as its foundation, but rather the young people who gave birth to it “were simply trying to find ways to pass the time, they were trying to have fun” despite them growing up “under the politics of abandonment", a condition which contained “the seeds for a kind of mass cultural renewal." [8]

The abandonment policy mentioned by Chang was one of the main goals of the segregationist planning policy implemented by Moses, clearly aiming to remove the ‘weaker’ sections of society from a city whose value began to grow more and more and in which the right to space was not for everyone. The construction of a major infrastructure project such as the Cross Bronx Expressway also hides the desire to create a strong and impassable demarcation—a wall, a border—hidden within a Trojan horse. The urban megablock then becomes a kind of desert island, characterized by a post-war landscape made up of empty, demolished buildings and scrap.

Within this environment, in August of 1973, DJ Kool Herc organized the first-ever ‘Block Party’ in the recreation room of his blocks that could accommodate just a few hundred people. The Block Party eventually became a foundational practice within the hip hop culture of the Bronx, as subsequently shown in the cult documentary film Wild Style, in which DJ Kool Herc played an important part. By illegally getting power from street lamps, connecting two turntables (the simplest musical instruments one can steal) and looping breaks, an extremely rich subculture was born and developed—although the process was never thought out or planned.

The same ability to ‘just make things happen’ is what enabled the development of the art of sampling. Lack of access to traditional instruments such as the ones used by funk musicians led to the use of the turntable and vinyl records as a musical instrument. This instrument allowed for small loops to be extracted, then repeated, reworked and reassembled. The mode of playing these instruments is called ‘scratching’ and is, in a way, violent—literally scratching the support where the loops were recorded.

the scraps transform themselves into the scenography of a bottom-up process of emancipation

Its musical origin, with roots in the blues, jazz, funk and the Zulu Nation’s Afrika Bambaataa’s Afrofuturism shows a futuristic projection towards an extreme vision of urban life, mixing African tribal features with avant-gardist visions of human futures. The four disciplines of hip hop—break dancing, rapping, graffiti art and DJing—as well as, first and foremost, the Block Parties serve as the tools for an emancipatory process from below: a segregated social class reconquering urban space. In the music that animated the block parties of DJ Kool Herc as well as in sampling, there is a visible philosophy of ‘the scrap’, of the re-use of little components. This musical process mirrors the urban space of the African American ghetto: the scraps transform themselves into the scenography of a bottom-up process of emancipation.

"Negro music has touched America because it is the melody of the soul joined with the rhythm of the machine,” states Michael Ford in Le Corbusier, The Grandfather of Hip Hop: Hip Hop Architecture and Theory. “It is in two part time; tears in the heart; movement of the legs, torso arms and head. The music of the era of construction; innovating. It floods the body and heart; it floods the USA and its floods the world. The jazz is more advanced than the architecture. If architecture were at the point reached by jazz, it would be an incredible spectacle.” [9]

The hip hop experience powerfully shows that the tools of urban planning and architecture that were applied in these areas are not at all adequate to address the issues that concern the contemporary metropolis. While, admittedly, "[Top-down urbanism] created value out of races and places that had seemed to offer only devastation” [10], the history of hip hop culture speaks to the need to change design tools, looking at a number of different practices. From the most ephemeral to the most tangible and concrete, partying, music, escapism and liberal arts can be elements which guide the reconceptualizing of urban deserts as radical new islands, making it possible to form autonomous cosmologies with their own conventions, which are in turn transformed into self-created regeneration opportunities.

3. Rave Culture and the Urbanism of Future Cosmologies

On May 14, 1995, an accident occurred in the streets of Camden Town. Two cars blocked the road while, for as long as possible until the damaged vehicles were removed, a spectacular improvised party started taking place. This action was the first of a series conceived by the Reclaim The Streets movement, the aim of which was bluntly made clear by its name: taking back the streetscape through an environmental vision rooted in the exclusion of cars. This action gave way to the Street Parade, a phenomenon that is now present throughout the world.

The methodology used by the Reclaim the Streets movement was borrowed from one of Europe's younger subcultures, the Rave Tribes, which eventually spread all over the world and inspired the contemporary clubbing world, including the Berlin scene that by now has evolved very far from its origins (and which some consider to be quite elitist). Already by 1973, in “The Planet as a Festival” treatise, Ettore Sottsass imagined a post-industrial society freed from the chains of labor through robotization and automation, the same utopia that animated Constant Nieuwenhuys' New Babylon and which today returns as a reference in the #accelerate manifesto formulated by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams in Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work.

This new society imagined by Sottsass exists in a continuous state of exhilaration—a permanent festival—made possible by mystical architectures reminiscent of sexual organs, with phallic towers that exhume vaporized psychoactive substances to be inhaled with every breath alongside the life-permitting oxygen. The drawings of Sottsass appear almost prophetic of the Castlemorton Common Festival of 1992, considered as one of the first rave festivals in history. Even though the term ‘rave’ dates back to the 1950s, it gained notoriety only at the end of the ‘80s, when it became synonymous with the subculture that organized unlicensed or illegal parties featuring the nascent Acid House sub-genre of electronic music.

The rave's illegal nature demanded nomadism and anonymity, and, alongside the other subcultures analyzed so far, the Rave Tribe phenomenon was made possible by urban decay and abandonment, specifically that of industrial ruins. The world of the Rave Tribes was born in the ashes of Fordist capitalism.

It is therefore not a coincidence that Detroit is the birthplace of one of the most important musical genres of this culture: techno. It was within the rusty industrial skeletons of that city that bodies started moving with the rhythm of a futuristic kind of tribal music, the nature of which was never heard of before, accompanied by the colors of freshly exuberant styles of fashion and the consumption of new psychoactive substances like ecstasy.

Music and altered states of consciousness transformed abandoned factories and forgotten industrial areas into new temples for escaping into other dimensions, for temporarily detaching oneself from stagnant cultures of the usual—and perhaps from the body itself. The towers of speakers and subwoofers that iconically recall primordial shapes and archetypes become altars for the celebration of the end of the world and the beginning of a new type of existence.

to not build a universal cosmology, but rather a micro-cosmology that functions at a different scale, parallel to many others

As we have seen, each of these subcultures can be seen to possess their own cosmologies—a unique system of meanings and conventions common to a group of individuals. Each one was born and flourished in relation to specific and precise architectural environments, integrating with them and interacting with their waste, modifying them and creating specific habitats which stand in opposition to the disparities produced by the monopolizing visions imposed on the city and the world.

From the appropriation of mainstream cultural products in the punk collage, to the fertile ground found by the Rave Tribes in the ashes of industrialization, to the reuse of musical samples and abandoned architectures in the case of hip hop culture, unlike ancient cosmologies, the cosmologies formulated by the subcultures we have examined focus on deconstructing order rather than ordering the disorder from which they themselves arise. This difference is substantial: to not build a universal cosmology, but rather a micro-cosmology that functions at a different scale, parallel to many others. They do not attempt to impose supremacy over other visions, but rather accept them, allowing for a plurality of existences and providing the opportunity to build a variety of forms of societies and cultures—and thus also multiple forms of architectural habitats in the form of autonomous but interconnected islands.

4. Dark Cosmologies and Potential Modes of Resistance

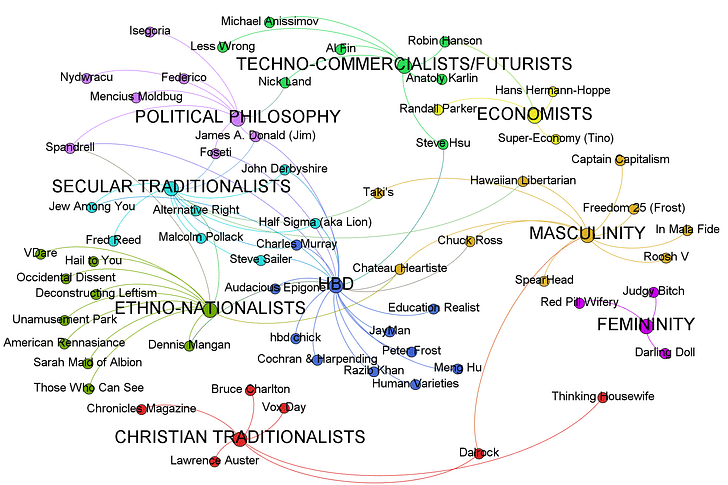

Are there contemporary cosmologies today besides that of neoliberal domination on a planetary scale? The ideology of Silicon Valley has roots in the counterculture movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. More recently, it has transformed into the Dark Valley of Neoreactionaries (NeoRx), a political theory and ideology well-expressed by the philosopher Nick Land as a "Gov-Corp", wherein society is "run like a company, ruled by a CEO” [11] (for more on NeoRx, please refer to the glossary below). Ideas like the Sea Standing Institute confront us with new cosmologies of escape for just a select few. Neoreactionaries envision something like a CEO-Feudalism. In an interview with Vox, the NeoRx political theorist and computer scientist Curtis Yarvin (aka Mencius Moldbug) imagines Elon Musk as a sort of future CEO-King of America. The Dark Valley, Dark Enlightenment and Neoreactionaries are all elements of an emerging cosmology, as said before, that was born, in part, from the counterculture movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s, but developed in a completely opposite and negational direction, with different goals, purposes, and actors. With their ideology, they are creating their own dark radical island for a chosen few. The thinkers of this doctrine have been able to spread and develop their elitist and (hyper)racist message through the internet, taking advantage of its unique characteristics (for more on the phenomena of “crypto-deserts”, or online subcultural communities, click here). They primarily formulate their ideology on websites such as LessWrong.com, ThedailyStormer.com, MoreRight.com, rather than on pen and paper or in more formal media.

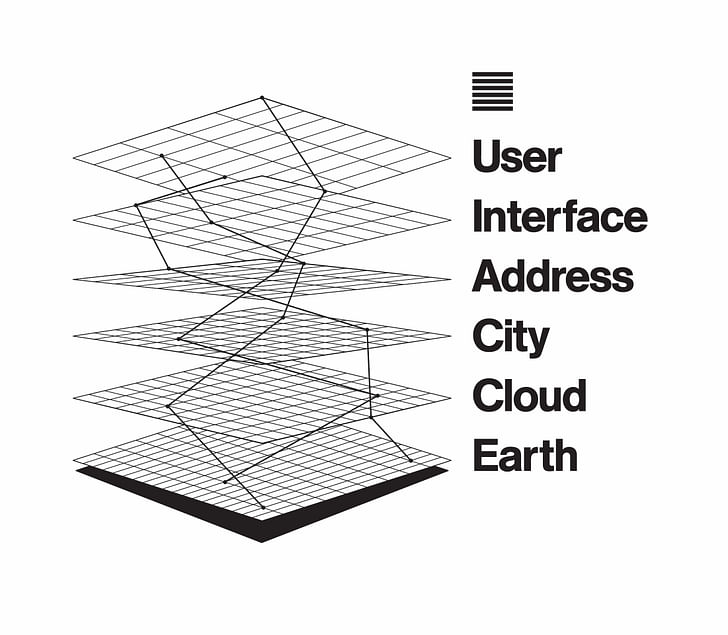

We strongly believe in the need for new external or parallel platforms to contemporary systems of progressive exclusion and hyper-racism. Such an alternative platform would require the appropriation of technologies and communication systems that are currently leaning towards oppression, coopted instead into the construction of new communities that could find space in the ruins of the post-industrial city, structuring new modes of exchange, production and coexistence. We believe that we can see examples of subcultures that act as platforms within the ‘The Stack’, “an accidental megastructure that resembles a multi-layer network architecture pile” recently formulated by Benjamin Bratton as a way to give life to something new (for more on The Stack, see the glossary below).

The idea of the ‘platform’—a term borrowed from computing language—as a new form of collective organization that structures a system of sovereignty can serve as a a foundational element in envisioning new cosmologies. One can imagine the architecture of platforms within The Stack as micro-cosmologies with their own languages and communication systems encoded independently. The alteration and change of sovereignty on a planetary scale combined with the opportunity provided by new technologies and communication systems allow us to open new doors and create new visions that respond to the need for microforms of independent societies, which would be able to function at a global level through systems of ‘Planetary Scale Computation’. But who controls today's ‘Planetary Scale Computation’ systems?

Which subculture—or, most probably, subcultures—will guide our society into the future? Is the cosmology that carries this vision of globalism not generated by a worldview that imposes Western culture through violence and supremacy over the planet? Are the examples recounted here not reactionary to this form of oppression? How global is this cosmology? Which are the streets where we will hold our future Block Parties and with what means? Are the refugee camps of today the equivalent pf abandoned factories or a segregated Bronx? If any of these questions are to be addressed, first we must consider the progressive polarisation of technological control. Access to Planetary Scale Computation systems are one of the main issues to be addressed in order to imagine new forms of communality at the margins of the city.

In Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary, the author Dan Hill highlights how necessary it is for design disciplines to focus on what he calls “the big picture" in order to escape from the shadows of the contemporary moment. [12] Using the long wave of riots and protests that started in 2011 as a departing point, including the first Occupy movement in Spain, Hill describes a world where it is no longer possible to apply conventional design methodologies, now surely doomed to fail.

Whether when dealing with environmental issues or the fall of the welfare state, the issues which Hill was confronting just five years ago (and which today have undoubtedly multiplied), make it clear that a new "strategic design vocabulary" is necessary. In a first analysis, Hill recognizes how the movements united by the #occupy hashtag have "this lack of faith in the core system" as a uniting force. The "big picture" that we need is a re-design of this core system—an effort that has been sparked many times in the past, such as by the countercultures of the ‘60s and ‘70s. The failure and subsequent manipulation and misrepresentation of these attempts (ie. the appropriation of their language by Silicon Valley, or their mutation into the NeoRx ideology) makes it clear that, today, it is almost impossible to rethink this big picture in its entirety. A better strategy might be to start from smaller constituents where one can perhaps envision evolutive expansions. Therefore it is necessary to understand in what typology of places and spaces this process can take place.

by observing and finding inspiration in these kinds of unconventional and largely overlooked practices, we can develop new design tools

What does examining these aforementioned countercultures provide in the way of useful strategies and tactics to achieve these goals for the future? They reveal at least two important clues. The first lies in their habitat and their relationship with space, where the deserts of marginalized contexts characterized by a ground zero of abandonment becomes a laboratory for new experimentations. The second clue is the need to rethink all aspects of human endeavor, building cosmologies that are expressed in new and unique languages, economies, aesthetic conventions and ways of communicating, as seen in the punk and Rave Tribe subcultures that evolved their own methods of value creation, completely external and parallel to norms.

In this sense, we believe strongly that by observing and finding inspiration in these kinds of unconventional and largely overlooked practices, we can develop new design tools that can be useful in bringing spatial practice, and the profession of the architect, away from unnecessary sterile discourses within the creative process and towards investing the effort of design in remodeling policy, economic, social and spatial structures—as well as the ways we live together.

If the world of design were to use already-established methods when confronted with politics and decision-making, its role will remain marginal. On the other hand, these subcultures provide visions of design strategies and tools that are involuntary yet effective in forming and establishing new spaces and possibilities. This dark matter requires and imposes a new formulation, which might just be found by looking at practices in the margins.

Glossary

Planetary Scale Computation: general name for algorithms, network structures and other digital innovations that redefine and challenge geopolitics and sovereignty centered on the nation-state. These algorithms distort and deform traditional Westphalian logics of political geography and create new territories in their own image. [13] [14]

The Stack: an accidental megastructure that resembles a multi-layer network architecture pile. More easily described as a platform. In Benjamin Bratton’s opinion, platforms represent a technical and institutional model equivalent to states or markets but reducible to neither. The layers of this stack are (from the bottom to the top): Earth, Cloud, City, Address, Interface, User. Even if they gather and subdivide their processes vertically in discrete jurisdictions, they co-occupy the same terrestrial horizontal position. [15]

NeoReaction (NeoRx): also defined by the self-professed NeoReactionary Nick Land as “The Dark Enlightment”. An anti-democratic and reactionary political doctrine. It is considered as the intellectual vanguard of the Alt-Right, grown from an “amoral libertine Internet culture “ and debates on the website LessWrong.com. NeoReactionaries do not advocate any central social organization. They envision a society run like companies, competing with each other, and ruled by CEOs. According to NeoRx forefather Hand Herman-Hoppe, this exactly coincides with feudalism. [16]

The second text for the series conceived for Archinect on deserts and radical islands makes an additional leap of scale compared to the first article, which examined the concept of the desert and the island from a historical point of view through theology, philosophy, cyberspace, and activism. This article aims to focus on the contribution that specific urban subcultures have made to the development of such radical islands, and to their own forms of social organization within unique urban contexts, which we can define as deserts due to the state of ground zero in which they were found.

To read the first installment, head over here.

1. Errickson, April. A detailed journey into the punk subculture: punk outreach in public libraries. University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, 1999, pag 7.

2. Savage, Jon. England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock and Beyond. St. Martin’s Press: New York, 1992, pag 229.

3. Rota, Luca. Punk! (“Punk”???). lucarota.com, 2 February 2015 (Translated from Italian by Elian Stefa).

4. Errickson, April. A detailed journey into the punk subculture: punk outreach in public libraries. University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, 1999, page 2.

5. Jeffries, Stuart. A right royal knees-up, The Guardian, 20 July 2007. 6. Bennet, Linda. Architecture and Anarchy, Archi-ninja, 2011.

7. Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five. "The Message". Sugar Hill Records, 1982.

8. Lurence, Rebecca. 40 years on from the party where hip hop was born. BBC, 21 October 2014.

9. Ford, Michael. Le Corbusier-The Grandfather of Hip Hop: Hip Hop Architecture and Theory, 16 October 2008.

10. Lurence, Rebecca. 40 years on from the party where hip hop was born. BBC, 21 October 2014.

11. Haider, Shuja. The Darkness at the End of the Tunnel: Artificial Intelligence and Neoreaction. Viewpoint Magazine, 28 March 2017.

12. Hill, Dan. Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary. Strelka Press, Moscow, 2012.

13. Benjamin H. Bratton, Wikipedia, last modified February, 27th 2017

14. Visualizing Complex Networks on a Planetary Scale, www.computation.llnl.gov, July, 3rd 2014

15. Review of Benjamin Bratton’s The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, www.rogerwhitson.net, July, 19th 2016

16. Haider, Shuja. The Darkness at the End of the Tunnel: Artificial Intelligence and Neoreaction, Viewpoint Magazine, 28 March 2017

3 Comments

This, is epic. Can't wait to dive in.

Thank you very much b3tadine and Chris. And thanks for the reference. we are gonna watch it. And yes Chris, it would be really amazing to have the possibility to develop an entire university course. So far we've just spoken about these topics in some lectures, but all of those stories, events, and movements have still a lot to say!

thanks again

Thanks for the excerpt Chris!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.