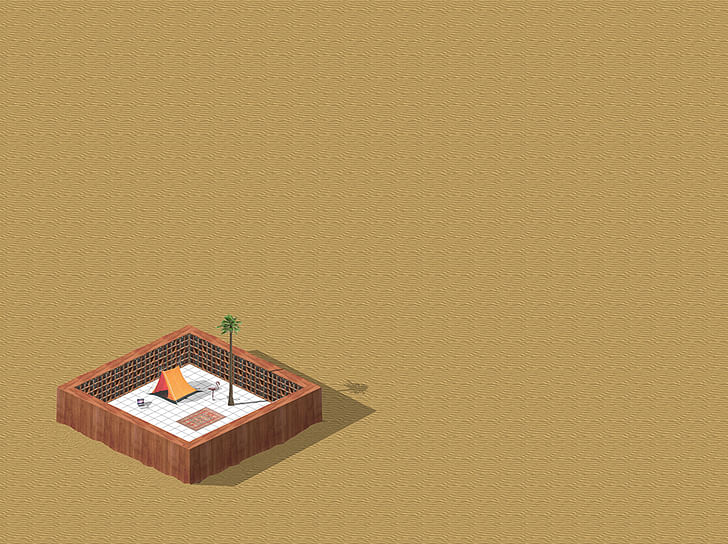

Looking for a picture that represents something related to the internet, we thought about the desert.

The internet was a desert in which everybody sought their own oasis. The internet was a desert because it was an uncontaminated territory where everything could happen, where everybody could envision their own world, their own parallel universe. The desert is an ascetic and mythical idea, both mystical and subversive. The internet went beyond a primordial, primitive and utopian stage and entered a new one in which people no longer have an adolescent vision of the generic absence of rules. An entire digital society has formed and established its own rules and constitutions. The borders of digital countries have been defined and, inside these borders, obviously, there are hermits. However, we can observe more and more the presence of rules that restrict the operating space and its freedom. The internet, over the course of many years, has been losing its subversive power.The internet was a desert in which everybody sought their own oasis.

It is essential to find new territories to resurrect utopia, to rethink collective life and imagine new forms of real and digital societies. It is essential to glean from the mythological role given historically to the desert. From the Biblical theology of the desert to Causes and Reasons of the Desert Islands by Gilles Deleuze, the concept of the desert and ascetic isolation has always assumed an important role within our society.

Today, our desert is the internet. We want to travel again through the history of the desert—a mythical place characterized by the existence of people who decided to push themselves to the limits of thinking in order to dream a new world.

From the physical desert, to the digital desert of today, to future deserts.

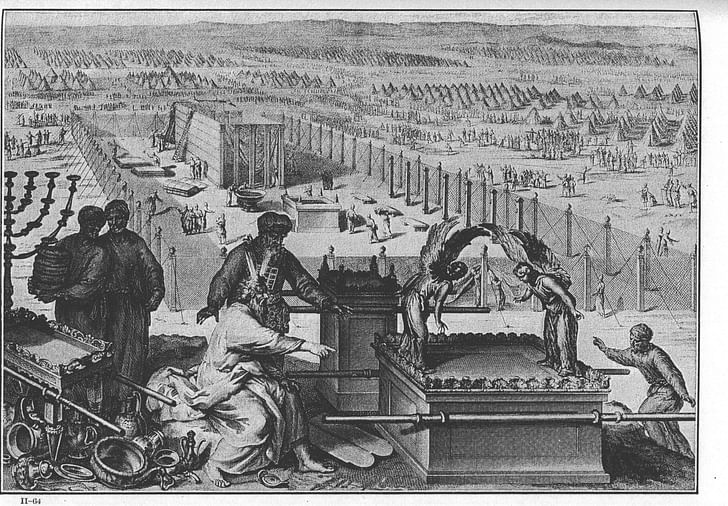

Biblical Theology of the Desert

The Bible talks about the forty days that Jesus spent in the desert, as it talks about the forty years the Jewish people needed to find the Promised Land of Canaan (Exodus). In the Bible, the desert is the place for rebirth and for personal purification. From the desert, people come back anew. It is an inhospitable place where life cannot exist, but, at the same time, represents a place of ascesis, where man can meet his God. For Christianity and for Judaism, it is the hermetic and the inhuman place, par excellence.The desert is where the Messiah will appear.

Reading the Old Testament, it is clear how the desert represents the opposite of life, of anthropization, of farmed lands and of pastures. It is the opposite of land transformed by the work of man. The desert, in biblical language, corresponds to a “waste land, an unpeopled waste of sand” (Deuteronomy 12:32),² where “wild animals shall meet with hyenas, the wild goat shall cry to his fellow” (Isaiah 34:14)³ and it is where the demon of the night, Lilith, lives. God drives his people through the primordial chaos, allowing them to live only thanks to his presents. The prophet Hosea, seeing Israel corrupted by other cults, hoped for his people to find new desert lands. In Israel, the desert is the place where you fall in love:

“I remember the devotion of your youth,

your love as a bride,

how you followed me in the wilderness,

in a land not sown”

(Jeremiah 2:2)⁴

The desert is where the Messiah will appear.

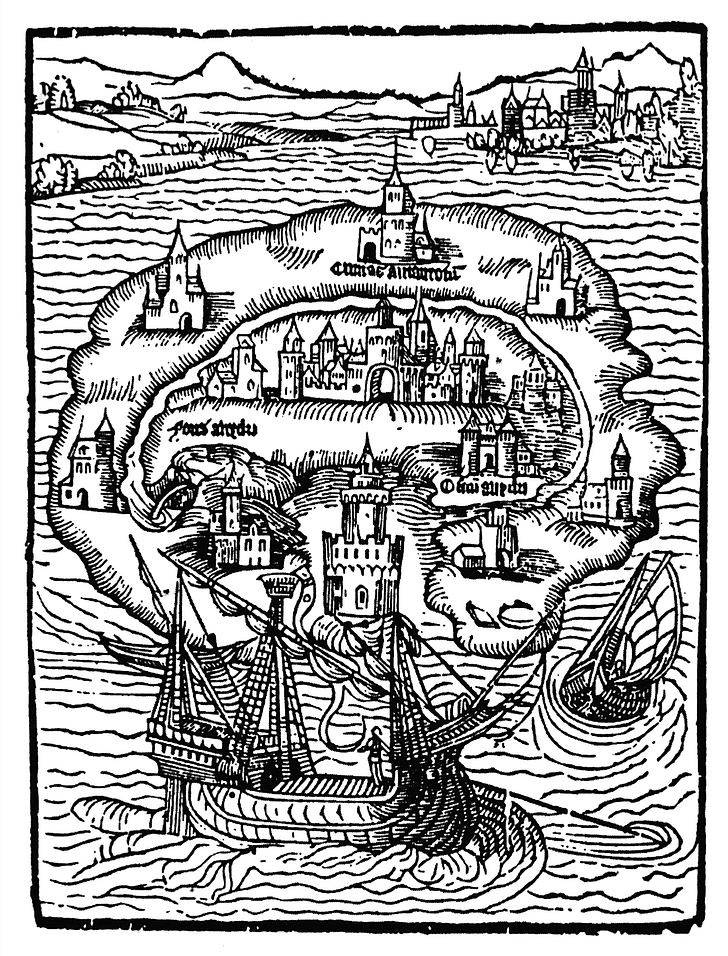

Radical Island

For the utopists of the 17th century, the desert is the white canvas for their stories. From Thomas More’s Utopia, to Fénelon’s Adventures of Telemachus or Campanella’s City of the Sun, deserts made of paper were the places in which the authors impressed their new vision of the world and of collective life. These tales were loaded with a strong pedagogical character for future generations. They narrate adventures in perfect utopian civilizations situated in magic places. One of the most important aspects of these utopian stories was the deep critique against the society of the time and against the royals who oppressed their authors. In fact, Fénelon and Campanella were persecuted because of these compositions. deserts made of paper were the places in which the authors impressed their new vision of the world and of collective life

In the seventh chapter of the Adventures of Telemachus, Fénelon makes Telemachus bump into Betica, a city that, like many utopias, is not based on great inventions, but rather on the elimination of each factor that could become an obstacle to human freedom. The foundation of the imaginary desert world of Betica is utopian equality. Professional specialisations and forms of interdependence don’t exist. Everybody is able to think about their needs:

“All of the inhabitants are shepherds or ploughmen, and craftsmen are absolutely banished. Each Boetician produces by himself and for himself anything he needs, such as cloth or tools.”⁵

Betica is Fénelon’s desert, because it is there that he realises the dream of a becoming the architect of his own life, of retaking the capacity to think and to create:

“All the arts that relate to architecture are useless to them: for they build no houses: it shows too much regard to the earth, say they, to erect a building upon it which will last longer than ourselves; if we are defended from the weather, it is sufficient (...) When they are told of nations who have the art of erecting superb buildings, and of making splendid furniture of silver and gold stuffs, adorned with embroidery and jewels, exquisite perfumes, delicious meats, and instruments of music; they reply, that the people of such nations are extremely unhappy, to have employed so much ingenuity and labour to render themselves at once corrupt and wretched.”⁶

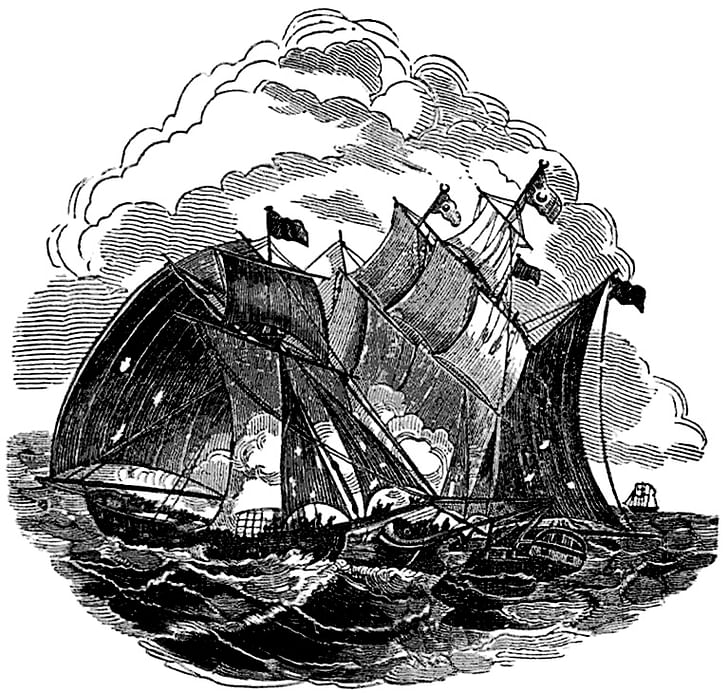

Pirate utopia

In the middle of the 17th century, in an aberrant framework of emerging capitalism, some chose the pirate life. In the Mediterranean sea there were different pirate communities that intercepted merchant ships, making spoils of them. They were a legitimate form of social resistance.

The Republic of Salé in 1620 was recognized and maintained independence until 1670.⁸ Unlike pirates, for the corsairs the objective was not to collect riches. Salé was the desert for the renegades. They challenged economic trade, thereby funding a new society based on ideals of equality and equal distribution of resources. Their diversity was the richness of the desert of Salé: it was inhabited by the dregs of the first stage of capitalism: Europeans converted to Islam, sufis, pederasts, Moorish women, slaves, heretic Jews, English spies, Irish rebels and radical heroes of the working class. It was a refuge for the renegades. The corsairs converted to Islam and were considered the scum of the seas since they betrayed Christianity. In the desert between sea and land a new society was imagined. Even the year was divided in a different way: only during the three spring months they went hunting for spoils. The rest of the year was dedicated to the most noble virtue: leisure.

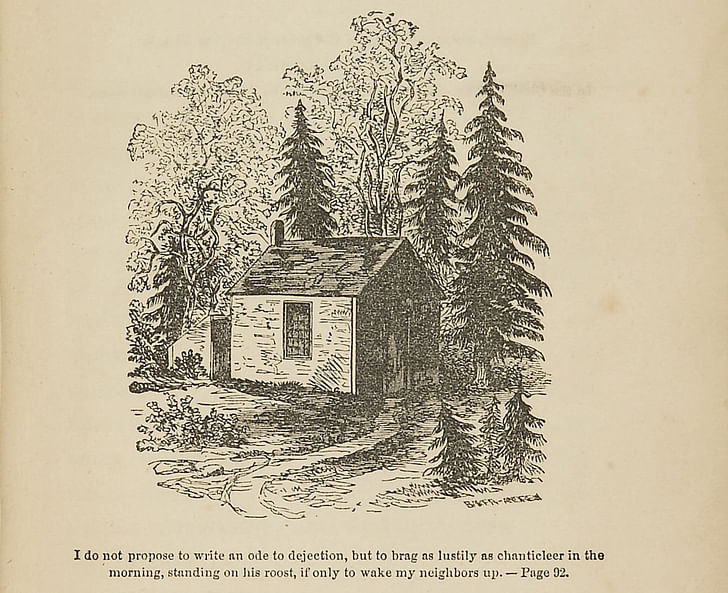

The woods of Walden

In 1845, at the arrival of modernity, Henry D. Thoreau experimented with a subversive escape into the woods around Lake Walden. In his Walden: or, Life in the Woods, a strong reaction against the rationalism that characterized Transcendentalism, he narrates this radical experience, which lasted two years, two months and two days. As an ascetic, Thoreau speaks about his metamorphosis with nature, his construction of a refuge, and his escape towards an interior desert. The writer of Civil Disobedience probably found inspiration in some brilliant disobedients of his time: Josiah Warren, founder of some anarchist communities in Ohio; Adin Ballou and his passive resistance, which also influenced Leo Tolstoy; or Charles Stearns Wheeler who built, four years before Thoreau, a shelter on Flint’s Pond.

The difference with Thoreau was that he excised the romantic aspect of these actions, substituting it with disgust and a critique of the principles of social behavior of that time. Thoreau’s desert rejected systematic work in favor of vagrancy; it enhanced the frugality and the research about nature and man; it showed the possibility of a more sustainable life by creating a new definition of richness and values in order to destroy the materialistic world. This was his idea of life—in a wood, in a cabin, in his own desert. Walter Harding, in The Days of Henry Thoreau wrote that “it is difficult to understand that a mother had ever clasped this hermit to her bosom; that a sister had ever imprinted on his lips a tender kiss.”⁹

Urban wilderness

Inspired by texts such as Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man as well as altered states of consciousness, even the counterculture movements sought their deserts. The rift they produced between the socio-cultural condition of that time, through a process of de-intellectualisation and emancipation of all aspects of life, was one of their fundamental actions. And, of course, one of their most powerful tools for these purposes was the self-published manual, whose contents were applied towards the utopian communes of those years. These manuals contained the tools through which one stopped being passive, regaining the capacity to shape their habitat and life. Their deserts were uncontaminated places far from the civilization, where they could envision a new kind of society. We can imagine the geodesic domes of the Drop City as patches that populate the collages of Superstudio’s Monumento Continuo, which was transformed into a natural place without borders, far from the old world.Jesus had his desert. We have the internet and we have become digital hermits

During the ‘80s and ‘90s, new deserts, closer to metropolitan life, were identified: abandoned places and forgotten architectures. The illegal occupation of spaces, rave culture and Hakim Bey’s theories about the TAZ (Temporary Autonomous Zone) exploded inside these metropolitan deserts.

For instance, during the activities and protests organised against the construction of the M11 highway in London, which implied the demolition of entire neighbourhoods such as Leytonstone, Leyton and Wanstead, a mixture of parties, politics and protests appeared, embodied in the Reclaim the Street movement. In 1994, the participants in the NoM11 campaign made Claremont Road a big livable installation that remembered and recalled some artistic and activist practices such as Palle Nielsen’s The Model of 1968. Some townhouses and a street were occupied to fight against the demolition. They were completely transformed into open-air living rooms with accessible, hanging webs, which blurred the line between public and private space. Claremont Road is a desert because it does not have a usual spatiality and it seems to belong to a virtual world. The artist-activist John Jordan affirmed that “if the utopia is a sort of map, Claremont Road would be placed on the coasts of this map. On the wild and unexplored coasts of Utopia.”¹⁰

Digital Walden

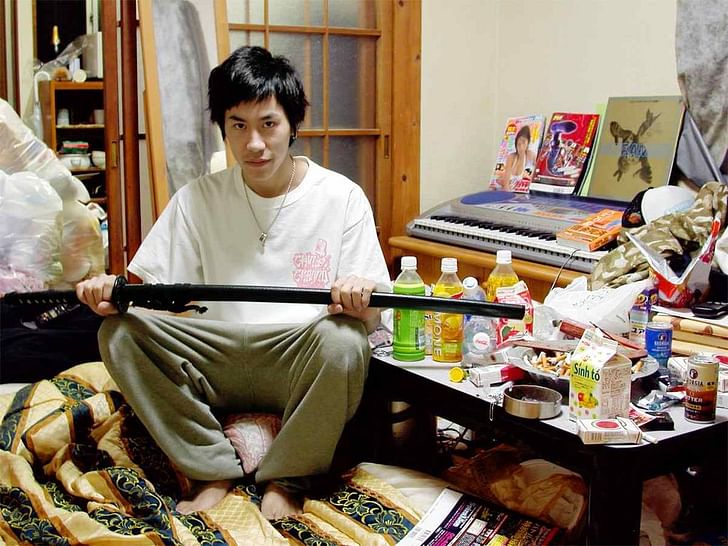

In recent years, the internet has definitively served as the place where people seek refuge and new worlds. Jesus had his desert. We have the internet and we have become digital hermits. A totalising and daily condition directs our utopian drifts on the web. In this desert, between codes and text lines, we can find our escape, our retreat in which, even for a little while, we can withdraw from the world. The digital hermit looks for silence or sound in the depths of the web. The so-called clearnet is made by 14.5 billions web pages (these are just the ones presented by the main browsers). Our digital habitat represents just 2% of the entire world of internet. We are in an overpopulated oasis within a very wide desert. And always more people walk through the path of what is dubbed the deep web.

the internet, our new real world, has become exploited for financial and security interestsHere the crypto-anarchist dream comes true: places free from the laws and the control of the bureaucracy system. In 1996, John Perry Barlow, in the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace manifesto defines the internet as the new home of the mind,¹¹ in which we can create a new society that will be “more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.”¹² Today this desert of cyberspace is increasingly populated by cyber hermits, what the Japanese call Hikikomori, which literally means “stand aside.” If we then look at Bruce Sterling’s novel Islands in the Net, now twenty years after the first edition was published, his vision seems like reality. The distinction between real and virtual space is increasingly fragmented and liquefied. Has acting in the physical world become virtual? Is the internet the new reality? In Sterling’s novel, economic power, manifested in the consumption of physical territory, has reached its ultimate stage, having found in virtual territories a new land of conquest. Today we face the growth of control, of hierarchy and of the mapping processes of the web. Silk Road, one of the most important markets of the deep web, was closed in 2013 by the FBI because it was considered “the most sophisticated and extensive criminal marketplace on the internet today.”¹³ Since the internet, our new real world, has become exploited for financial and security interests, has its visionary and subversive nature progressively been extinguished?

Paradoxically, the eyes of control concentrate on virtual space through very strong regulation. Today, the most important dose of control works in cyberspace, where everyday our identities and privacies are violated. The myth of crypto-anarchist cyberspace, seen as a separate universe created by humans, with a deep distinction between the internet and the real world— a desert without any kind of regulation—does not exist anymore.

Crypto-Territories

Today, the most radical action we can do is disconnect. Now that the internet has become the new hyper-regulated reality, where are the new territories we can escape to? Where can we dream of new collective forms of society? Where can we envision the dead crypto-anarchist dream? Where is our Walden? Has the real world become our desert again?

We need maps of real crypto-territories, of the places in which we can subvert unhappiness. While the world migrates towards the web, there are more and more empty—and physical—spaces free of regulatory control.Today, the most radical action we can do is disconnect

In our cities there are places that have to be restored and requalified, because they are seen as ‘hood’. In reality these places, thanks to the absence of control and planning, are the ones that can still avoid the imposed order that has already invaded cyberspace. We need to change our point of view about them and about the concept of degradation. They are reserves of freedom, rights and diversity, where it is possible to envision and experiment with new forms of living. “It’s a paradox that the places thought to be the most uninhabitable turn out to be the only ones still in some way inhabited,” writes the Invisible Committee.¹⁵

Since the origins of cyberpunk, the virtual world was seen as intangible: a parallel and alternative universe, where the thinking being was free from the constraints of physical space. But the new metropolitan deserts, the crypto-territories of the real world (thanks to their architectural infrastructures and the administrative disorganization) are the Tor Network and Silk Road of real life. Between the ruins of our cities, we can find our crypto-deserts—the real equivalent of the deep web. Disconnection and escape strategies have become a form of resistance against the nausea and paranoia of hyper-connection. Accordingly, here we can start envisioning new primordial communities, new metropolitan and nomadic tribalisms, in order to craft a poetry of spatial disobedience for all those desires that now are repressed even in the cyberspace.

1. Hosea 2:14, The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers

2. Deuteronomy 12:32, The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers

3. Isaiah 34:14, The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers

4. Jeremiah 2:2, The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers

5. Marc Brabant, "Condemned by the utopias of radical individualism: hat's wrong with architecture?", San Rocco #8: What's wrong with the primitive hut?, December 2013, 64

6. Salignac de La Monthe-Fénenlon, The adventures of Telemachus, the Son of Ulysses (Manchester, 1847), 146

7. Peter Lamborn Wilson, Pirate Utopias, http://hermetic.com/bey/pirate-utopias/a-christian-turnd-turke.html

8. Bernard Vincent, Perché l'Europa ha scoperto l'America, (Torino: E.D.T.,1992), pag 104

9. Walter Harding, The Days of Henry Thoreau, (New York: Dover Publication, Inc, 1982), 355

10. Julia Ramírez Blanco, Utopías artísticas de revuelta, (Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra, 2014), 67 (translated from spanish by Eugenio Cosentino)

11. In Peter Ludlow, Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias, (Cambridge: the MIT Press, 2001), 61, monoskop.org/images/4/42/Ludlow_Peter_Crypto_Anarchy_Cyberstates_and_Pirate_Utopias.pdf

12. Ibid., 27

13. Samuel Gibbs, “Silk Road underground market closed – but others will replace it”, The Guardian, 3 October 2013

14. Hito Steyerl, Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?, in The internet does not Exist, (New York: Sternberg Press, 2015)

15. The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection, (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009), 72

4 Comments

gentlemen, excellent text and thank you for introducing us to your work which is very interesting!

as I read this text, nostalgia for an internet I believe many of us once knew, might be the equivalent of this current "deep web", and many of your points made me imagine what the internet felt like when it was a desert as you describe it.

when you say "The internet was a desert in which everybody sought their own oasis" I figured yeah sure - Facebook, etc.. but then I remembered when I was a teenager and you reminded me of what it once was - you inspired this "internet art" piece?!?! I don't know, just thought this was once what the internet was _______________ (look for the word enigma)

looking forward to digging into your work and the new desert?

again, great text.

THE DESERT

by Jim Morrison

The Desert

–roseate metallic blue

& insect green

blank mirrors &

pools of silver

a universe in

one body

excellent quote here. you guys are on it.

Can the house still be considered, on one hand, as a private space in the era of the “sharing economy”, and on the other, as the last existing encrypted space? — as the last shelter in an ascetic desert, a place in which to disconnect from society and where our deepest desires can come true?

Dear Max, thanks for your commentary and for citing Jim Morrison! We really appreciated your term "nostalgia". You can feel it since the beginning in the title "the internet WAS a desert". You mentioned the question "can the house still be considered..."! It's a fundamental question for us. The domestic landscape as a personal utopia. It is at the base of many of our works. Thanks again Parasite 2.0

thank you for responding. I read all your projects and looked at the photos from the bottom up (on website). Your fundamental question you developed is in my opinion the only thing left to discuuss and way beyond the way Heidegger looked at it (technology and dwelling) or even how Massimo Cacciari wrote about it.

the phrase "last existing encrypted space" is genius on many many levels. exciting work!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.