Decentralized computation, virtual machines, cryptocurrencies: these terms seem to linger in shadows, conjuring abstract images of the “dark” web that lurks beneath the glossy surface of the screen. Architecture may be becoming “smart,” but we still perceive its domain to be brickwork instead of the tangled fiber optic cables it obscures – the walls that physically enclose rather than the signals that pierce.

Even on a digitally-native platform like this, architecture in the digital age appears as a representation more than something immanent to clicking, scrolling, swiping. Browsing the web, for example, has spatial ramifications – as does hosting a library of architecture renderings on an overheated server. Yet, architecture on the internet is still mostly perceived as a translation (of the physical to image, or of print to screen),Architecture on the internet is still mostly perceived as a translation, rather than a transformation that could potentially reconfigure the practice itself rather than a transformation that could potentially reconfigure the practice itself, and likely has already. But, for a growing contingency of architects, the form of architecture, as a field and object, may be on the brink of a radical mutation. Blockchain technology, which drives digital currencies like Bitcoin and smart contract platforms like Ethereum, not only offers the possibility of entirely reorganizing the profession, but is itself already a spatial practice.

Over the course of several emails, I talked with FOAM, a self-titled “decentralized architecture office,” aka ĐAO – the crossed "D" differentiates their name from DAO, the acronym from which their name is derived, in reference to “decentralized autonomous organization." Helmed by Ekaterina Zavyalova, Nick Axel and Ryan John King, FOAM has employed blockchain technology for several projects, including recently an installation made in conjunction with the Chicago Architecture Biennial. They helped explain the fundamentals of this promising cryptographic technology, in terms of both its architectural and broader relevance, and detailed their own compelling work with it.

As an introduction, could you briefly explain how blockchain technologies work in layman's terms?

The blockchain is a peer-to-peer time stamping technology first introduced by the cryptographic digital currency Bitcoin. The technology is essentially a decentralized public ledger that contains a record of all transactions and activity that occurred on the network in chronological order. Every node on the network comes into a consensus about the system-wide order of events within a given time interval, and simultaneously publishes this information within a cryptographic block, which is then linked to all previous blocks to form a chain. Thus, the blockchain works as a shared public ledger, which all who use the network can access. [The blockchain] is essentially a decentralized public ledger that contains a record of all transactions and activity that occurred on the network in chronological order

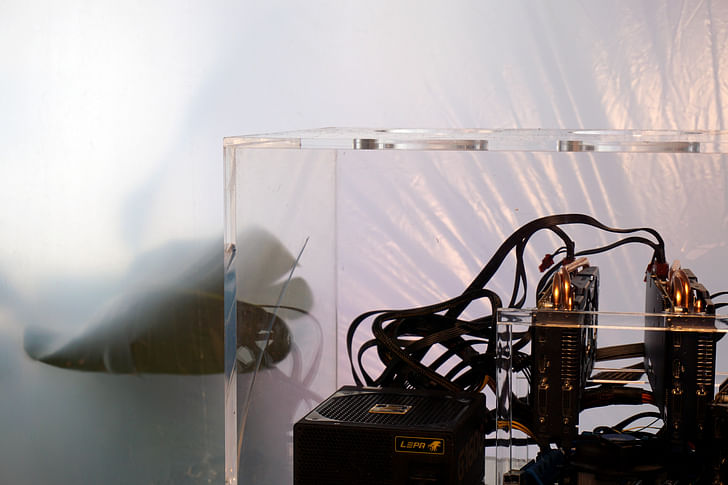

The information contained on the blockchain is secured by a decentralized network of powerful computers called miners, which anyone can set up and run. Mathematically complex problems, which are both energy-intensive and computationally-difficult, are posed to mining computers, which then attempt to solve these equations by calculating in what are called “hashing algorithms”. When a calculation is solved the miner is rewarded with a block. This block contains all network transactions since the last block was found on the network. A block is found every 10 minutes by one of the miners on the network who receives the intrinsic token, Bitcoin, as a reward for its work, and the block is then added to the blockchain. This serves as the economic incentive for an actor to spend money on the electricity it takes to operate a mining computer.

New digital protocols, such as Ethereum, have developed their own blockchains that are able to be programmed for decentralized applications comprised of smart contracts. These smart contracts make it possible for computer code to execute automatically and transparently, operating as a programmable world computer. Ethereum has a block-time of 12 seconds, as opposed to Bitcoins 10 minute blockchain, allowing transactions to be published much faster. In general, this method of recordkeeping for urban data is being developed for environmental sensors and internet of things devices.

How can this technology be implemented in an architectural context?

This technology should already be viewed in an architectural context. The process of securing the blockchain via mining computers has immediate spatial ramifications. Mining consumes energy and produces massive amounts of heat. This thermal condition is often treated as a problem as the largest mining operations require either large cooling fans or highly air-conditioned warehouses. For example, the artist Yuri Pattison produced a sublime film about the architecture and landscape of Bitcoin mining operations in the mountains of China. However, protocols like Ethereum are working to develop new blockchain verification protocols that will allow the technology to scale into everyday life without intensive energy consumption.

The process of securing the blockchain via mining computers has immediate spatial ramifications.In addition to using blockchains as a decentralized register of value for a currency, “smart contracts” can be written to represent agreements between parties that could range from a conventional contract involving a mortgage, to voting systems and reputation protocols. “Smart contracts” eliminate reliance on centralized third party services because the contract itself is an intermediary.

What Ethereum presents is a vision of a Decentralized Autonomous Society made of decentralized autonomous corporations and organizations (DAC/DAO). The classic example of a DAC is a version of Uber where a self-driving a car owns itself, collects cab fare from users and uses the profit to maintains its services and distribute the surplus to a set of stakeholders. In a recent studio taught by Joseph Grima at the Architectural Association called ‘Crypto-Architecture,’ the prompt states: “What if a home could own itself?”

So it seems that one of the primary advantages of blockchain technologies for architecture would be within the realm of the contract, essentially opening up new models for both sides of the designer-client relationship. In general, architecture rests on rather outmoded standards for this relationship. How do you imagine the architectural transaction could evolve with blockchain technology?

Architectural transactions could evolve in a number of ways with blockchain technology. For example, from the point of view of the business model, architecture could move away from client-designer relations that rely solely on fixed design and hourly fees. Instead they could exchange equity in the built environment in the form of smart contracts that distribute cryptographic tokens that represent share or equity in the agreement.

Internally, reputation systems for architectural designers could open new freelance markets for both workers and firms. Office projects could scale as they grow instead of offices maintaining a set number of employees, allowing a more liquid flow of work between offices for designers.

Going off this, is it possible to imagine that something like Ethereum could possibly lead to the elimination of the firm as an economic necessity – i.e. as one of the few viable paths to fiscal stability for architects today – and instead to a diverse and even shifting forms of collective practice, as well as more individualized relationships between the client and designer(s)?

Absolutely. Imagine a decentralized architecture office that distributes equity and shares in the built environment and comprises a mesh of users: investors, clients, designers and established offices. Over time each user, while working on separate projects, would obtain equity in built work and procedural reputation. This would allow for a more collaborative approach between designers and introduce a new schema for an architecture business model based on “spatial investment portfolios.” With equity in completed projects the design portfolio doubles as an investment portfolio.

How could blockchain technology be implemented in the design process?

We are not advocating for the implementation of blockchain technology in the design process, per se. Architects have already developed a multitude of fantastic design processes. Blockchain technology can be implemented into the design process in the sense that architects should now be applying design thinking to bridge digital and physical environments. For our current condition of endless quantification, the architect needs to create social and cultural exchange by drawing connections and generating unprecedented experiences that are interstitial to digital life.

Digital life now includes blockchain technology and its endless possibilities. In order to restructure the built environment and disrupt geographies of power the spatial ramifications of this technology need to be investigated to the fullest. Ubiquitous sensors, energy consumption, network power, thermal radiation and atmospheric conditions are all elements of the blockchain and how it is already impacting space. The creativity of the architect and its design process can then be applied to researching this domain, while this domain, in turn, dissolves traditional architect-client models.

Do you think this technology could be utilized to enable more self-funded projects?

Yes, one of the most exciting things about the blockchain is that it will enable architects to initiate their own projects. We have already seen this take place via Kickstarter. However, with Kickstarter funds are donations, and there is not only no simple way to organize collective interest in the project, but there is also no real way for donors to then participate in the project, and/or be compensated for their contribution.

The blockchain will enable equity crowdfunding, decision making tools to allocate funds, and the ability to scale the project with interested parties.

On a platform where users are a mesh of investors, clients, designers and established offices, projects can be initiated by architects and brought to scale and fruition while consciously distributing the financial stake in the built environment.

So tell me a bit more about FOAM. Who comprises the office? How did you all get into blockchain technologies?

FOAM was founded by Ekaterina Zavyalova, Nick Axel and Ryan John King with the vision to create a decentralized architecture office and open industry platform. After participating in competitions and workshops that touched on the technology, we all inherently saw the potential in the blockchain as a secure, durable, networked database for recording transactions and agreements. This would address what we see as an outdated business model in the profession, while at the same time furnishing tools for architects to initiate their own projects. Imagine a decentralized architecture office that distributes equity and shares in the built environment and comprises a mesh of users: investors, clients, designers and established offices

The project that predates FOAM and served as its impetus was Foamspace, an installation built for the IDEAS CITY Street Festival at the New Museum for Contemporary Art by the SecondMedia design team. As a temporary work of architecture, Foamspace explored the speculative relationship between decentralized infrastructure and the production of the built environment. The installation was made entirely of factory-standard EPS geofoam blocks, which additionally served as a visual metaphor for the bitcoin blockchain.

There was a digital component to the project, as well, where a token called ‘Foamspace Coin’ was created on top of the bitcoin blockchain and given to anyone who signed up for a custom digital wallet. This token represented a membership in a community. Within the parameters of the competition entry, the ambition of the project was to organize a community of architects and allow for members to vote and propose on future projects after the material from the installation was resold on the secondary materials market.

This project had a number of relative shortcomings, which served as the starting point of reflection for FOAM. Firstly, building a platform on top of the bitcoin blockchain is incredibly limited and Ethereum had yet to launch. In our lack of smart contracts, the project demonstrated their potential use and necessity to negotiate and secure agreements between, for example, engineering consultants, software developers, teammates and institutions about how the project should proceed.

How are you organized? What does it mean, in practical terms, to be a “decentralized architecture office"?

We try to stay organized through the app Slack, as well as email and scheduled Skype calls. The levels of involvement are rather fluid and new parties are consistently joining the conversation and collaborating on different types of projects. However, as the technology evolves, what it means to be a decentralized architecture office will evolve along with it. Eventually we see making day-to-day project decisions and office decisions on the blockchain with tools such as Boardroom.

How would you characterize the political orientation of FOAM? (cryptoanarchist? libertarian? accelerationist? communitarian?)

As the founders of FOAM we certainly have an interest in crypto-anarchist and accelerationist writings. However, in a practical sense we understand that, to quote the theorist Benjamin H. Bratton, the “transposition of [the blockchain’s decentralized architecture] into a commanding armature means centralization.” Having said that, we believe that as the technology evolves, an open industry platform for architecture should be inclusive of a number of different political positions.

Tell me a bit about some of your past projects. In particular, I’m really interested in the Tropical Mining Station, as well as the attendant talk-series, the Art of Economy.

The Tropical Mining Station was an architectural installation we put on at Future Firm. The Art of Economy was a day-long series of presentations and discussions that took place inside the installation. Both were produced and organized by FOAM as partner events for the opening weekend at the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

The Tropical Mining Station was a space produced by extracting the surplus energy from the process of mining Ethereum to produce a heated space

The Tropical Mining Station was a space produced by extracting the surplus energy from the process of mining Ethereum to produce a heated space. Custom miners were built that funneled excess heat and required airflow to inflate a pneumatic space, which became a spatialized node on the decentralized network.

As a symposium, The Art of Economy focused on the triangular relations between decentralized technology, architecture and the office-form. It was not only designed to increase the awareness and interest in blockchain technology from within the discipline, but also actively chart out its fields of implementation. By being held within the installation, participants were confronted with a technology that the profession has yet to take much notice of. We brought together a diverse group of thinkers who did in fact have much to say on the matter. The day was organized into two panels, ‘Spatial Politics of the Blockchain’ and ‘Decentralized Labor Practices and Distributed Production Networks.’

This interest in inflatables brings to mind the work – as well as perhaps the utopian aspirations – of groups like Ant Farm. More broadly speaking, the idea of a decentralized architecture office recalls aspects of many of the utopian practices of that era (60’s and 70’s, primarily) – from Constant Nieuwenhuys to Superstudio. Can you speak to this apparent filiality?

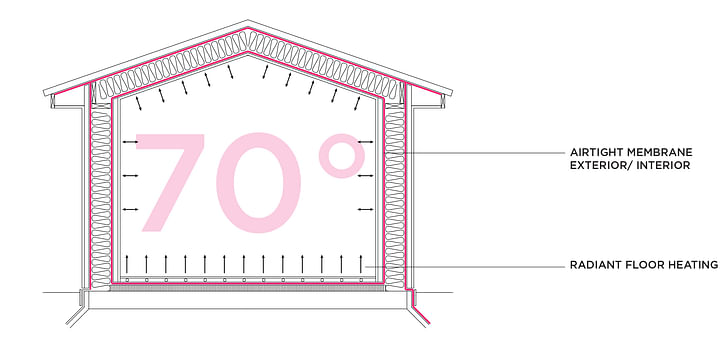

A critique of past utopian practices could be the lack of engagement or understanding of material production and the full industrial process. We are very interested in the origins of material in factory standard form and their circulation on the market. Further, the pneumatic membrane of the ‘Tropical Mining Station’ was made from industrial roles of reinforced polyethylene film. While we are interested in Ant Farm, Superstudio and the New Babylon project, introducing questions of thermal energy, the economics of mining and global decentralized networks presents an updated schema in a sense of these past practices.

Further, through our research we have developed more practical applications for these installations. While the inflatable architecture of Ant Farm remains to be integrated into everyday life, Passive House design actually employs a plastic membrane to prevent thermal leakage and create an airtight space. Within this context, the ‘Tropical Mining Station’ can be seen as a demonstration of a new type of Passive House, which utilizes a new kind of radiant heating, the miner, and an architecture of gradient conditions of atmospheric pressure and thermal boundaries.

Finally, what other projects is FOAM involved in? Any plans for the future you’d care to share?

We are pursuing a number of projects and collaborations leading to an open industry platform and decentralized architecture office. If you would like to participate in their formation please get in touch!

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.