The Anthropocene is a contested name for "the era of geological time during which human activity is considered to be the dominant influence on the environment, climate, and ecology of the earth." As the fourth installment of the recurring Architecture of the Anthropocene series, this piece looks at a design problem that is larger, and perhaps more important, than any other imaginable.

1. In 1981, a group of experts from various fields—from architecture to geology to semiotics—convened to work on what is likely the most difficult and important prompt ever assigned: design the façade of a massive complex intended to house the largest stockpile of nuclear waste in the world.

Rather than face a street, this façade would point towards the sky: the sole visible element of building extending deep into the ground. No mere plasterwork would do; rather, this work of ornament would have to last for somewhere between ten thousand and a millions years, this work of ornament would have to last for somewhere between ten thousand and a millions yearswhich is much longer than any work of architecture has ever lasted. And while most façades are designed to be inviting, the primary program for the marker system of the Yucca Mountain repository of nuclear waste was to keep people away.

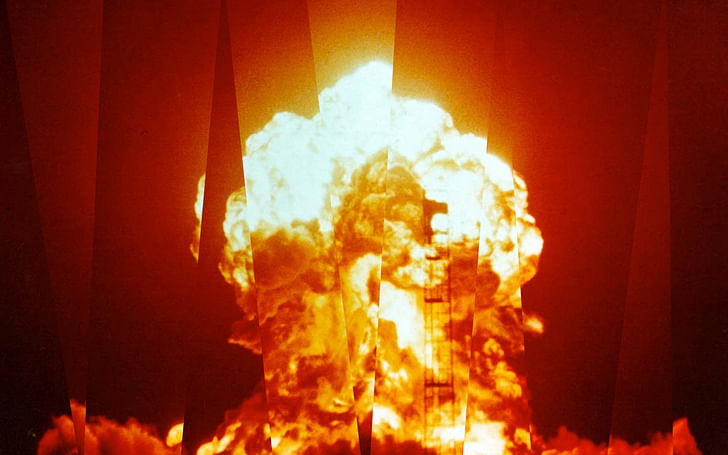

Since becoming the first and only country to ever unleash on other humans the force of a neutron split in two, the United States has steadily accumulated enough nuclear waste to existentially threaten life on the planet—with nowhere to safely contain it. Up until very recently, the US government was proceeding with plans to build its first long-term storage site for the waste in Yucca Mountain, Nevada. The building complex itself—a giant artificial cavern hollowed out of the low-slung mountain—would eventually be filled in by 108,000 regular shipments of spent nuclear waste. This would take forty years, and each shipment would carry 1,000 pounds of radioactive material while passing through nearly every state. Then the whole thing would be capped with concrete.

Afterwards, presuming the stability of the facility wasn’t disturbed by an earthquake (it’s adjacent to a fault line) or erosion (the mountain is porous and wet), the nuclear waste would have to remain untouched for around a million years. But since that’s longer than the experts could predict the stability of Yucca Mountain (or any mountain, for that matter), they settled on 10,000 years—more than double the age of the Giza pyramids.

But written language has only existed for about five thousand years, roughly 1/200th of the time a marker would need to successfully convey the dangers of nuclear waste to unaware future generations. So the façade would have to communicate non-linguistically. Thomas Sebeok, the well-known semiotician, noted as much, observing that mythology and religion have been around much longer than written language. So he proposed the creation of an Atomic Priesthood, an elite group of people tasked with preserving the knowledge of nuclear waste for centuries (alongside a political, cultural and religious system developed around them). Stanisław Lem, a Polish sci-fi writer, suggested biologically encoding plant DNA with warning messages, while Emil Kowalski, a Swiss physicist, believed that if the material was buried far enough out of reach, the possibility of disinterment would be precluded to all but societies with at least the scientific knowledge that we possess today. The French writers Françoise Bastide and Paolo Fabbri suggested breeding a special type of cat that would glow when in the presence of radioactive material. Since domestic cats have been part of human culture far longer than written language, it seemed safe to presume that this will persist into the future.without any satisfactory design for the marker system, the whole project could end in ruin.

About a decade later, a group brought together by the Sandia National Laboratories to discuss the same problem for a different waste repository site—the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant—took a more architectural approach. One proposal comprised a field of thorn-like sculptural objects that would instill a sense of fear. Another idea was a massive black square that would suggest an abyss or void, with the added benefit of getting very hot. A third idea was to create a massive set of concrete blocks—basically a Nolli map rendered into reality—that would be impassable and therefore, hopefully, ominously unintelligible.

None of these proposals ever made it past the design phase, but construction of the repository began nonetheless. The marker system was, in a sense, considered a supplement added to the already difficult task of designing an impermeable structure. The ornament was understood to be subservient to the work. Yet, without any satisfactory design for the marker system, the whole project could end in ruin. The ornament, it turns out, was inseparable from the structure.

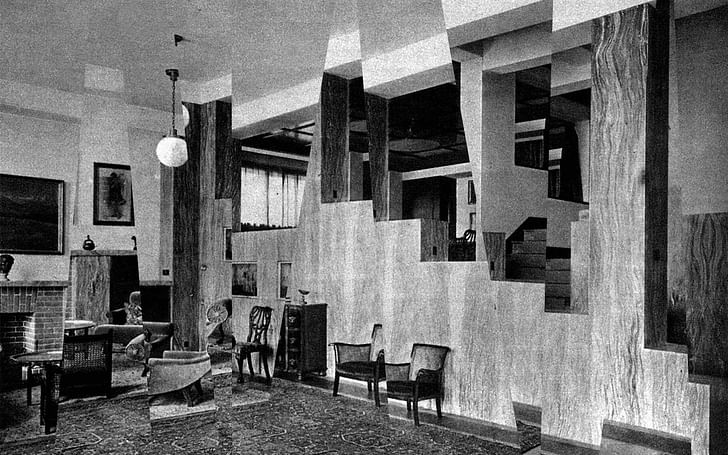

2. Incidentally, these discussions began just one year after Paolo Portoghesi commissioned some of the world’s leading architects to design the Strada Novissima—an indoor street of only façades—for the first International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale. The conversations centered around a site just 80 miles from the Las Vegas Strip, where, only a decade earlier, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown had gleaned a great deal on the semiotics of architecture by studying the city’s signs. According to a typical narrative, these two events were significant in what is usually described as architecture’s postmodern turn, marked, in part, by the return of explicit considerations of ornament after decades of denigration by orthodox modernists.

In fact, the denigration of ornament is older than modern architecture, and usually follows a formula that goes something like this: ornament is supplemental—this superfluity renders it structurally unnecessary if not also outmoded. “Ornament, rather than being inherent, has the character of something attached or additional,” writes Leon Battista Alberti. “Only an adjunct,” Immanuel Kant calls ornament, “and not an intrinsic constituent.” Style is conceptual ornament and, therefore, unnecessaryAnd then, from perhaps ornament’s foremost modern denigrator—or at least, most vocal—Adolf Loos, in "Ornament and Crime": “The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects.” And, for Loos, buildings should count as utilitarian objects.

Loos was an architect deeply concerned with time. He rebelled not only against the historicists of his era, but also those that attempted to stake novelty in the creation of a new style: the Secessionists, who inscribed above their eponymous building, “To every age its art and to art its freedom.” In Loos’ view, style in the modern era constitutes an attempt to rescue one’s time through the production of a quasi-spiritual aesthetic ethos, a sort of false consciousness that lends an era transcendental meaning. Style is conceptual ornament and, therefore, unnecessary.

Loos wanted to demystify architecture, to understand it as just another form of work, like tailoring or farming. Unlike art, architecture has to please everyone, it has to function, it “serves some practical purpose”. While his work was in fact so distinct that, famously, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria despised and avoided it, Loos rails against architecture that draws attention to itself. “Why is it that any architect, good or bad, desecrates the lake,” he asks in "Architecture". Architecture by architects contrives to declare itself as such, rather than fitting into its landscape and context.

Walls crack open. Warnings mutate into decoration.According to Loos, art is “a private matter for the artist.” And there is only a “little part” of architecture that constitutes art in Loos’ view: the monument or the tomb. But no tomb is actually private; a monument is not for the dead but for the living. So what does Loos mean? He writes that the aim of a work of art “is to make us feel uncomfortable”; it is “concerned with the future and directs us along new paths”. The tomb-monument, which seemingly serves to provoke reflections on a past life, actually orients us towards our own inevitable future demise, towards an awareness of time and its strangeness—and, in that, it makes us uncomfortable. In other words, art sometimes has its function; architecture sometimes requires ornament in order to work. Here, an apparent supplement to the text—a footnote-like addition—fundamentally alters its central argument.

Tombs, like other forms of art, trace strange routes through time. Their meaning is far from self-evident and is enmeshed in larger social contexts. Their ornamentation can crumble or become unrecognizable. Walls crack open. Warnings mutate into decoration. In a way, neither form nor structure nor function define the future of such architecture—accidents do.

3. In the grand scheme of things, it was very unlikely that archaeologist Howard Carter would find anything at all when he removed a panel on the unadorned wall of King Tutankhamen’s rock-hewn tomb. About a decade before, another archaeologist had suggested that the riches of the Valley of the Kings—or as it was known in antiquity, The Great and Majestic Necropolis of the Millions of Years of the Pharaoh, Life, Strength, Health in The West of Thebes—was already tapped-out. A series of workers’ huts covered a stone that was essentially discovered on accident, and excavated on a hunch, only to lead to a tunnel dug that had been dug by robbers several centuries before. That tunnel opened into a simple, sparse and empty room that was quite unremarkable compared to other royal sepulchers in the region. In fact, it was this very lack of ornament that is said to have encouraged Carter to keep looking.

It is even remarkable that the name of King Tutankhamen is known to us at all. It is quite strange that the tomb wasn’t completely divested of its content by looters; it had already been broken into at least twice several months after his burial. helping to spur a cultural trend that left traces in as far-flung places as Hollywood Boulevard and the Las Vegas StripThis preservation is in part attributable to the fact that the entrance was buried in rubble—a type of accidental ornament, which like many other façades, hides the contents of a building rather than expressing them. This happened during the excavation of a later tomb, some centuries after, by workers who very likely didn’t even know the name of the young pharaoh whose tomb they disregarded (if they had, they may have re-used his tomb, as was common practice).

If the tomb had been found only a century or so earlier, its contents would likely be on permanent display in the Louvre or the British Museum or the Pergamon Museum, instead of travelling internationally every few years as they do today. Were it some other figure who was searching for the tomb, without the help of robust media attention, they may have given up, instead of helping to spur a cultural trend that left traces in as far-flung places as Hollywood Boulevard and the Las Vegas Strip, where the Luxor Las Vegas pyramid was being constructed at the exact same time that the United States finally stopped blowing up nuclear weapons 65 miles northwest in the desert.

4. “The ornament is an outsider that always already inhabits the inside, an intrinsic constituent of the interior from which it is meant to be banished,” writes Mark Wigley in The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida's Haunt. Function and form, structure and ornament, can never be strictly divorced, and architecture can’t be ripped from the larger context in which it’s enmeshed. This is true of a housing project or a nuclear waste repository. Likewise, the margins of the project description—its conceptual ornaments, addendums, and footnotes—haunt the body text. More damning than the failure to produce an adequate marker system for the Yucca Mountain waste repository was the politics surrounding it. Local opposition spearheaded by Senator Harry Reid stalled the use of the site, which was already under construction, for more than twenty years. Finally, under President Obama, work ceased and so the byproduct of nuclear power plants sits in caskets adjacent to the facilities where it was produced. Election cycles proved more influential than an existential threat.Vitrivius and Palladio would become contemporaries to each other and to us.

Architectural styles, like elections, come and go. Buildings rise and crumble. From the perspective of geological time, all of architectural history would account for less than a single brick in the largest city imaginable. Instead of “styles” or “periods” shuffling at the rapid pace of an individual human’s lifespan, we might have the pre-concrete and the post-concrete (around 300 BCE), or the pre-window and the post-window (around 6500 BCE). Vitruvius and Palladio would become contemporaries to each other and to us.

The increasing awareness of geological time—millennia rather than days—that comes with living in a world marked by climate change and nuclear waste should enforce this perspective. Yet, even today, sometimes style is discussed in terms of progress—as if some secret churning machine produced the thousands of small, insignificant trends in taste and material in sequential order. Forms don’t autogenerate; they respond to exterior conditions—economics, politics, zoning codes, volatile environments—that cling to them like invisible scaffolding. Architecture likes to play a game with itself: miming autonomy, yet constitutively contingent.

There is no building without its supplements, its qualifying conditions, its supportive ornament. Rather, architecture is a bundled assemblage of concerns that together produce a form in a place. The consequences of what is included or excluded from this assemblage matter. If sustainability is seen only as something to be tacked on to a design, then the results tend to not actually be very sustainable, causing ripple effects that can extend far beyond the site. Yet it’s impossible to center every possible concern—ecological, political, or social—when designing a building. And current professional and economic configurations demand specialization, the privileging of one concern over others, for the sake of differentiation.There is no building without its supplements, its qualifying conditions, its supportive ornament.

Here, anecdotes with no substantial connection to the practice of architecture today are intended to decorate an essay about ornament, organized by the excessive logic of the accident and the coincidence. Or: a few musings on ornament are meant to embellish a story about design failures and eventual extinction. Meanwhile, there are around 83,000 metric tons of spent nuclear waste (or more) in the United States, mainly the afterthought of a production cycle activated to supplement the energy produced by oil. This waste will threaten human existence for a million years: a fact that stands, if at all, on the outside of architecture. It is too large a problem to be incorporated into architectural thinking in any serious way and it doesn’t really have any relevance to the day-to-day work of an architect. Yet, strangely enough, the success or failure of a single building and its façade has more bearing on the future of the discipline than any other edifice built in the 12,000 year-long (or more) history of architecture.

5. Today, there’s only one site in the country that is intended as a long-term storage facility for radioactive material produced by the American nuclear defense program: the Waste Isolation Pilot Project, an underground complex in the desert of New Mexico. A visitor to the site today might consider the geography of this desert region barren, although, in reality, it is home to mottled rock rattlesnakes, hoary bats, mule deer, horsehair worms, and countless other species of plants and animals. A visitor to the site just 250 million years ago would be under at least 600 meters of water, perhaps face to face with a creature that looks a bit like a squid or a mollusk (but certainly not a dolphin or even a dinosaur, the latter of which would not appear for at least another 20 million years or so).

In fact, the site was chosen because of this ancient, marine history. After the sea evaporated, it left behind a massive salt basin including a complex cavern system, the best known of which is the Carlsbad Caverns. The salt layer is nearly impermeable, which will hopefully prevent radioactive leakage, and could have the added benefit of “salt creep,” the self-sealing tendency of salt caverns. After years of development, construction, and testing, in 1998, the EPA declared there was "reasonable expectation" that the facility could contain the radioactive material stored there. So, less than a year later, the first shipment arrived from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, north of Albuquerque.

After that, 72,422 cubic meters of waste were shipped by train and truck to the facility by December 2010. If all goes according to plan, shipments will continue for 25 to 35 years. But an accident has already brought the plan under scrutiny and forced the temporary closure of the facilities. In February 2014, a single drum of nuclear waste—number 68660—ruptured. The explosion was caused by workers who put the wrong type of kitty litter—an absorbent material often used for cleaning up radioactive leaks—into the barrel, inadvertently causing a disruptive chemical reaction. Specifically, the workers had accidentally purchased Swheat Scoop, a “natural wheat litter” brand, when they should have gone for the non-organic stuff.

This feature is part of Archinect's special October theme XXL. For more on the extra-extra-big of architecture, check out related features here.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.