In horror fiction, a house is usually haunted in one of two ways: either a building is inhabited by the ghosts of dead humans, or the structure itself is animated by a strange, non-human life. Edgar Allen Poe’s short story “The Fall of the House of Usher,” an influential achievement of the genre, falls into the latter camp; the horror of the House of Usher can never be properly pinned down because it pervades the setting itself. But what’s so scary about a living building?

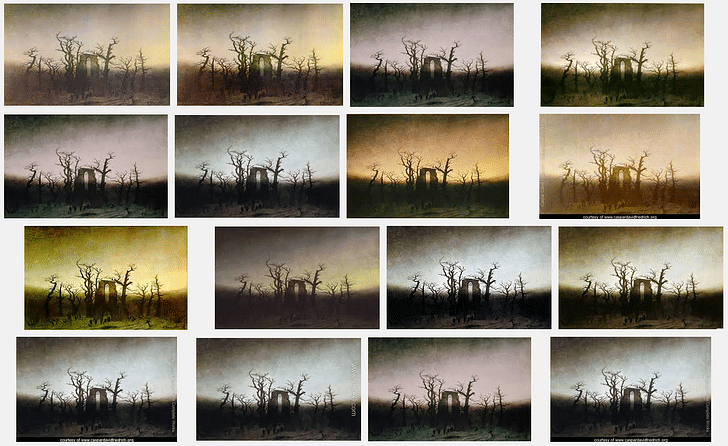

In Poe’s story, Roderick Usher, the last in a long and uninterrupted chain of patrimonial inheritance, is convinced his ancestral mansion is a living, sentient being. This conviction manifests as a “mental disorder” characterized by an overwhelming sense of foreboding and dread, which the man summons his old friend – the narrator – to help alleviate. For Usher, the building is enlivened by the arrangements of its stones, the “many fungi which overspread them,” and the surrounding vegetation of “decayed trees.” The narrator notes that the crumbling mansion seems to emit a “pestilent and mystic vapor, dull, sluggish, faintly discernible, and leaden-hued.” The haunted house constitutes an entire ecosystem: unintelligibly massive and pervasive. The House of Usher presents an image of architecture as a gaseous and immaterial object that extends beyond the limits of structural form. Dwelling within this “atmosphere” adversely affects the human residents, as if by breathing the air they become haunted as well. Here, the haunted house constitutes an entire ecosystem: unintelligibly massive and pervasive. The House of Usher symbolizes the dissolution of any boundary between architecture – as a strictly human space – and non-human life. In the story, horror is a failure of exclusion that extends even into the confines of the body, turning humans into haunted houses, as well.

The built environment – and our relationship to it – is actually much closer to the House of Usher than we might like to imagine, a reality that is brought into startling and unavoidable intimacy by the Anthropocene thesis. Fungal spores are present in the atmosphere, often in high numbers, at all times except for when the ground is covered in ice or snow. Like most non-human lifeforms, fungi don’t respect property boundaries and also inhabit indoor spaces where they are perceived as contaminants. Like most non-human lifeforms, fungi don’t respect property boundaries. As a matter of fact, homes provide fertile ground for fungi who enter into a complex relation with the activities and patterns of the human inhabitants. An individual’s showering habits, choice of indoor plants, preference for carpeting all contribute to producing as personalized and unique a living situation for their fungal roommates as for themselves. Of course, often humans inhale these fungal spores and get infections as the organisms take root in their bodies. An infection changes the way a body functions and operates, just as the House of Usher affects the physical and mental state of its inhabitants, robbing them of their agency and independence. Likewise, the fungal world is as hard to escape as a haunted house. Rather than eliminating fungi, air conditioning ducts often play host to them and disperse spores into the air, at the same time as they create carbon emissions and raise global temperatures.

And aside fungi are bacteria, which operate in the built environment similarly to the strange interdependence between the House of Usher and its occupying family. Despite fervent slathering of hand sanitizers, we are constant hosts to bacteria that we track into our bedrooms and on to our beds. Researchers scrutinizing a series of lived-in homes found that each constitutes its own microbiome. Moreover, every family produced its own identifiable combination of bacteria, with the humans serving as the “primary bacterial vector.” When an individual stays in a previously-occupied room, their bacteria will rapidly colonize the entirety of the space, even in the case of short-term residences like hotel rooms. Humans and buildings co-produce a unique bacterial atmosphere. In turn, microbes can also colonize the human body. A home constitutes its own microbiome. The parasitic protozoan Toxoplasma gondii can cause miscarriages, stillbirths, blindness, and seizures in a human host, who can become infected from their house cats. The parasite requires the specific conditions of a feline stomach to sexually reproduce. Research has shown that if a rat eats a cat’s excrement, Toxoplasma gondii can rewire the neurology of the infected rodent, making it sexually attracted to feline urine and therefore much easier prey. According to some theories, the parasite also changes human behavior, producing “crazy cat people syndrome.” Often times, our attempts to eradicate microbial life just make things worse. The overuse of antimicrobial soaps has created what are called “Super Bugs,” or deadly drug-resistant viruses, many of which will proliferate as temperatures increase and rain patterns change.

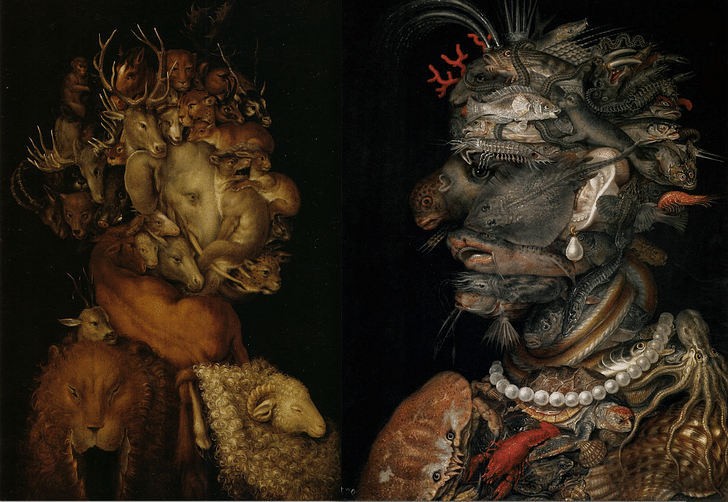

In reality, a building has a living coating that is unconcerned by property lines, aesthetics, or surface edges. In fact the walls contain their own worlds: the rats behind the drywall or the ants in the ivy or the birds beneath the eaves. The urban fabric may have pavement but its also a fertile ecosystem, of which humans are just one aspect. Architecture is part of an uninterrupted field teeming with biologic and geologic life, as well as the air that’s been filtered through our own lungs. The urban fabric may have pavement but its also a fertile ecosystem. The fears of the narrator of “The House of Usher” are actually grounded: buildings do emit their own atmosphere, but they require non-human eyes to perceive. A snake, which can sense infrared thermal radiation, might see gaseous plumes of heat where we see structural form. If we could sense other types of radiation, a city would appear as a mass of shifting, interconnected rays emitted by cellphones, wifi signals, and radio transmissions. Soil, water and rocks also emit radiation. So does concrete, as scientists have recently noticed throughout Hong Kong, where the local granite that is pulverized to make building material has higher than average radionuclide content. In actuality, architecture is enmeshed in a fabric that withdraws from the imagined binary of interior and exterior, from the delineation of voids from forms. “…Nothing is ever empty, the dialectics of full and empty only correspond to two geometrical non-realities,” writes Gaston Bachelard (The Poetics of Space, 1994: 140).

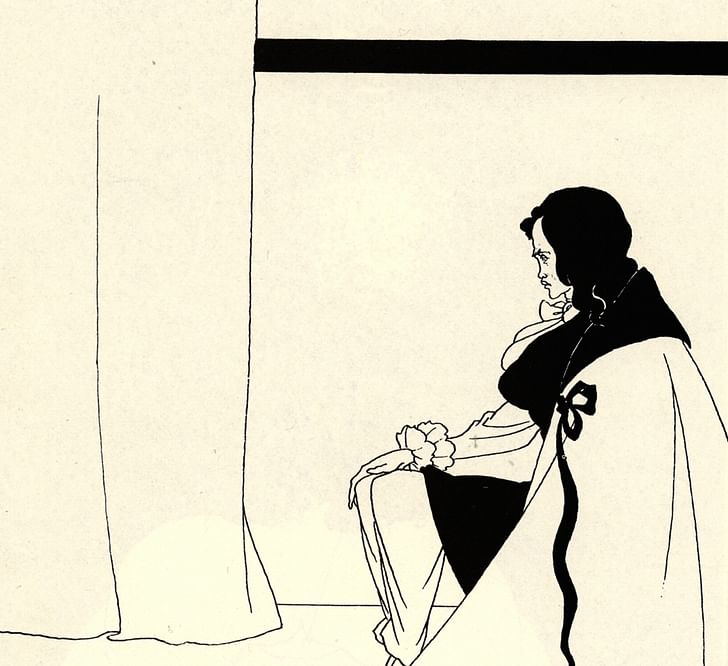

For Roderick Usher, awareness of this reciprocating, living architecture comes at the expense of his own vitality. While the “mansion of gloom” emits its own miniature biosphere and is described in distinctly anthropomorphic terms, conversely, the narrator finds it difficult to connect his old friend to “any idea of simple humanity.” He is described as pale and thin, “cadaverousness of complexion.” In Poe’s story, the House of Usher drains its human inhabitants of life. The narrator compares his friend to an opium-eater, a fitting analogy considering that drugs are perhaps the most obvious expression of the takeover of the human body and subjectivity by a non-human thing. Interestingly, Usher does not suffer from a physical disease but rather, as the narrator describes, “morbid acuteness of the senses.” Attunement to the life and sensual specificity of non-human objects causes a sensory overload. Attunement to the life and sensual specificity of non-human objects causes a sensory overload. Notably, those objects that are most often relegated to their use-value for humans are the ones that cause him the most physical suffering; “the most insipid food was alone endurable; he could wear only garments of certain texture; the odors of all flowers were oppressive.” Awareness of the vitality of the non-human world, as well as one’s interdependent relationship with it, turns eating into an act of cannibalism, clothing into an overcrowded prison of fibers, and the cutting of a rose into a beheading. This is the true mechanism of “horror” in the narrative, which could alternatively be called the uncanny experience of ecological awareness in the Anthropocene.

Humans are horrified by the idea that the body, like the house, may not be as airtight a container against foreign agents as we imagine; that they too are part of and constituent of ecology. The internet abounds with lists of disturbing invasions of the living body, from fir trees and pea plants growing in people’s lungs to maggots crawling inside of a man’s scalp. These stories are able to make our skin crawl, to disturb us in a way that few other things can because, deep down, we know that we too are filled with foreign bodies. The human is always already thoroughly non-human. Whether microflora in our stomach or viruses in our bloodstream, the human is always already thoroughly non-human. Sometimes, this notion can appear beautiful. “We are stardust, we are golden,” croons Joni Mitchell with scientific accuracy: the human body is about 40% composed of the detritus of exploded stars. But we are also bacteria, iron, water, viruses, parasites, calcium, magnesium. When we chase a dose of probiotics with a rub of hand sanitizer, we express an ideological confusion about the relation of the human body to its environment.

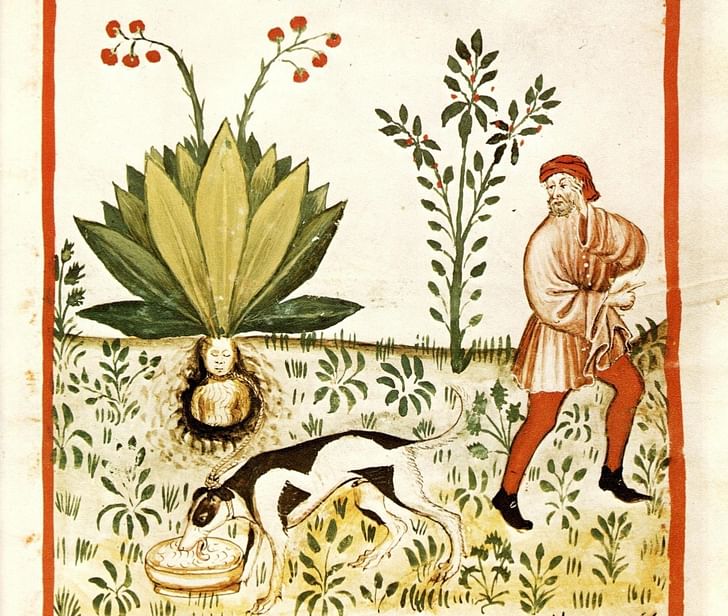

Persistent throughout most haunted house stories is that the building somehow resists anesthetization, in some cases even becoming antagonistic to humans because of their efforts to inoculate the space against anything non-human. In the case of the first season of the FX show American Horror Story, the ghosts of a house defiantly remain rooted to the place despite the constant redecorating of new homeowners, all of whom are quickly murdered by the feuding specters. In a series of flashbacks, the house transforms into different iterations of the type of bourgeois interiors that litter magazines like Dwell or Architectural Digest, but the house remains haunted. When a developer hoping to bulldoze the structure makes an offer on it, the ghosts simply kill him. The classic horror story “The Rats in the Walls” by H.P. Lovecraft is closer to “The Fall of the House of Usher” in that there are no individual, humanoid ghosts. Instead, the house is alive with a looming, non-personified specter. In the story, a man purchases the ruins of his ancestral home and, despite an extensive renovation tantamount to a reconstruction to modern standards, the site still remains haunted down to an ancient and disturbing core. The narrator first experiences this in the loud thrashing of swarms of rats in the walls. The story is horrifying in part because it expresses the victory of the pest over us and our arsenal of modern cleaning technology.

Like a haunted house that violently resists being sterilized, our attempts to exclude “pests” and other non-human lifeforms from both our houses and our bodies often end ups up backfiring, such as with the use of airconditioning to filter fungi or antimicrobial soap to eliminate viruses. Additionally, while rodenticide may kill rats – which have historically plagued human populations – later their corpses are often eaten by a beloved cat or a “non-pest” animal, who then succumbs to what is called secondary poisoning. Othertimes, a human child eats the poison instead of a rat. DEET is used by workers to repel mosquitoes, vectors of horrible of diseases. But instead of contracting malaria, they can’t sleep, their moods change, and their mental capacity becomes greatly reduced. In such cases, efforts to protect humans actually ends up hurting them. This can be compared to an autoimmune disorder, in which the body mistakenly attacks itself in a “quasi-suicidal fashion.” Because the Anthropocene thesis entails that human activity affects all other ecologic, geologic, and biologic systems, conversely, no body or space can ever be exclusively human. Attempts to eradicate non-human life often express the ignorance of humans not only to the complex mesh they inhabit but also the complex mesh that our own bodies constitute.

Because the Anthropocene thesis entails that human activity affects all other ecologic, geologic, and biologic systems, conversely, no body or space can ever be exclusively human.

In the last century, there were several attempts at “pest extermination” on a grand scale. In Maoist China, one of the first major projects of the “Great Leap Forward” was the “Four Pest Campaign.” Initiated in 1958, the campaign targeted rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows, which ate farmers’ seeds and thereby “robbed them of the fruits of their labor.” People would loudly bang pots to frighten the birds who would have to keep flying until dying of exhaustion. Nests were destroyed and eggs were shattered. It was not only sparrows that were shot from the sky, and the campaign led to the near extinction of all birds in the country. Ironically, rather than increasing crop yields, insects like locusts proliferated without any predators, consuming grains and furthering the “Great Chinese Famine,” which claimed the lives of at least 20 million humans.

After being found to effectively eliminate mosquitoes, the chemical DDT was actively sprayed throughout North America and Europe in the mid-twentieth century. Trucks used to drive down suburban streets and spray clouds of the chemical as children would run behind, playing in the vapors (as is memorably portrayed in Terrence Mallick’s Tree of Life). Malaria was basically entirely eradicated in these regions. But in 1962, Rachel Carson wrote The Silent Spring, exposing DDT as not only carcinogenic for humans, but also responsible for wide-scale disruption of ecological processes, in particular devastating birds. The publication of the book led to the 1972 ban on the agricultural use of the chemical. The Silent Spring can also be credited for helping to launch environmental movements. Fundamentally, Carson exposed not only the hubris behind human endeavors to mold ecology to its own desires, but also the violence.

Today, we are living inside of the ‘Holocene extinction’, the intentional and accidental genocides of entire species by humans. In the last forty years, half of the Earth’s wildlife has gone extinct, the full extension of the rationality behind our incessant attempts to anesthetize the world. This mass extinction feels like finding out that life is a horror story, in which ‘you’ are the monster. Like for Roderick Usher, realizing that your home is not only alive but sentient comes at a cost. After all, driving mechanisms of the extinction event pose significant, existential threats to Homo sapiens as well. On a deeper level, awareness of it effectively disintegrates the barrier erected by humans against the non-human world, collapsing the fragile boundaries of the conceptual as well as architectural space of anthropocentrism. In the last forty years, half of the Earth’s wildlife has gone extinct, the full extension of the rationality behind our incessant attempts to anesthetize the world.

According to the standard literary distinction, terror refers to the anticipatory state preceding an experience while horror refers to the feelings that occur afterwards. Devendra Varma writes, “The difference between Terror and Horror is the difference between awful apprehension and sickening realization: between the smell of death and stumbling against a corpse.” In the “The House of Usher,” the narrator notes that inside the house, objects he had “been accustomed [to] from [his] infancy” now stir up “unfamiliar fancies.” Rather than objects coming alive, here horror emerges from realizing that they always were alive. Likewise, the Holocene extinction is horrifying, rather than terrifying, because we realize it’s already happened and continues to happen. Global warming is horrifying not because of predicted events – extreme weather, widespread drought and famine, resource-driven conflicts – but because these are already happening.

Meanwhile, Roderick Usher can be described as engaged in a type of posthumous dying. Properly speaking, he “died” before the events of the story took place with the recognition that the anthropocentric model of human life can only occur at the expense of other lives. The exclusive elevation of human life constitutes a conceptual – as well as physical – genocide of other lifeforms; in the context of Poe’s short story, the converse recognition of other lifeforms manifests as illness in the human subject. The difference between Terror and Horror is the difference between awful apprehension and sickening realization: between the smell of death and stumbling against a corpse. Usher’s suffering can be diagnosed as symptomatic of the claustrophobia produced by finding an overabundance of life where one once saw nothing. Alternatively, his sickness can be understood as the state of an individual conflicted by the failure of their epistemological conditioning to account for perceived reality. Similarly, we experience a sickening nausea when we realize that we are the producers of an on-going mass extinction largely because of our ideological refusal to grant an equal category of “living” to non-human things. This nausea is not unlike the feelings we get when we realize how thoroughly “non-human” our own bodies are, because, fundamentally, they are two aspect the same realization. With each news story about mass extinctions or global warming, we become increasingly aware of the autoimmune disorder that is afflicting something like the “social body” of humanity. However, the cure withdraws from accessibility. Do we become Jainists, sweeping ants out of our path? Do we make space in our houses for rats, letting them bite us and accepting the diseases they carry as a sort of moral retribution for the historic and continued actions of the species we were born into? Or do we dig our heads in the sand and our drills into the ground?

If Edgar Allen Poe had written his story about just a living house, it wouldn’t be so terrifying. The horror emerges from the relation of the human resident to the living architecture. If a plant had grown in the lungs of a cow, we would not find our skin crawling. If crops didn’t fail, Mao likely would not have stopped the “Four Pest Campaign.” Horror, at least in this case, remains caught up in producing the same autoimmunity disorder of which it is a symptom. That is to say, this disorder, which could also be called the ecological crisis, is not just autoimmunitary but also schizophrenic. Not only is the house haunted, but so am I. Not only have we mistaken who and what constitutes a threat, but we have also mistaken what constitutes “the body.” The Anthropocene thesis shows me that my body is not quite my own, but rather filled with other things. Likewise, humanity as a conceptual body begins to fragment and disintegrate, becoming enmeshed in something much larger and much more complex. Not only is the house haunted, but so am I. The question is learning how to live – instead of continuing to die – with and among so many other living things.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

5 Comments

Great piece Nick on many levels. Fungi is in it's own kingdom, not plant or animal, and humans are a lot like fungi on many levels as well.

One of your points reminds me very much of this image from OMA's Rebuild by Design for NYC, and it has a horror quality to it...

(by the way the large skyscraper on the right is actually in Hoboken, NJ, across the river)

In Log 32 Ross Exo Adams has a great essay about resilience -

"No longer the space of extensive urbanization or of the boundless quantification and circulation of resources, in this project what stands outside of the city is merely the textureless, nameless other side of the urban - a space absolutely devoid of qualities yet equally limitless. Paradoxically, therefore, Rebuild by Design can also be said to perpetuate the same perverse fantasy of a world without exteriority - the fantasy of a world that, precisely because of climate change, has been canceled out." (p. 139)

yeah nic, loved this. the idea of a fabric of ecologies that enmeshes house/home, us/residents and our interior communities really invoked some great imagery..

Thanks Nam, thanks Chris. Re: Rebuild by Design, certainly agree that the OMA entry is chilling, not just because of that barrier wall. Interboro's entry presents an interesting counter, seemingly working with "natural systems" like tidal forces, estuaries, etc as partners in creating habitable spaces (for humans and non-humans), rather than as combatants.

"And aside fungi are bacteria" - Is there a groundbreaking paper on the reclassification of Fungi that I have not read?!

Fungi classification. http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fungus Two sentences in.....I know it's wikipedia, but should do. Not bacteria.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.