Shawn Keller is the President of C.W. Keller + Associates, an engineering and fabrication company headquartered 45 minutes north of Boston in Plaistow, NH. I’ll sheepishly admit that, despite their long history, until a handful of years ago I was only vaguely aware of the office and their work. I first came across them after spending an afternoon at the Boston Harbor Islands Pavilion construction site watching formwork go into place, and since then their name has come up with increasing frequency in discussions about fabrication shops really pushing the capabilities of digital tools.

Shawn and his team have been quick to embrace technology to compliment not only how they create, but also how they engage their clients. What I find most impressive is that over the years as the scope of their work and client-base has grown, the craftsmanship of the work itself hasn’t suffered. If anything, it has matured alongside their relationship with their tools, a reflection of the culture of exploration and experimentation that seems to permeate C.W. Keller as a whole.

C.W. Keller is involved with a number of projects at a variety of scales, but as far as fabrication companies go you’re probably not on many people’s radar. Let’s start with a little bit of the background behind the company and how it’s grown.

The company was started by my father and I'd say the first ten years were probably the same path that a lot of woodworking companies take: residential kitchens and libraries. Where we really hit a milestone was commercial work where we had the opportunity to work on Origins cosmetic stores. There was a 15 year run where we were rolling out 40 to 100 stores a year and it forced us to grow the infrastructure of the company to be able to deal with working on a national scale.

At that point we were really trying to figure out what we wanted to do. We started to gravitate towards those projects that other shops were saying no to. I would say that during the late 90s through mid-2005 we transitioned out of retail and became more of specialty fabricators. We then started to get a few opportunities to look at cast‑in‑place concrete work, and the first major project that we were asked to look at was the Boston Harbor Islands Pavilion by Utile Architects.We like to iterate constantly.

That really cascaded into some fairly significant projects for us over the past nine years. We still do quite a bit of interior feature design work, but we're using a lot of those strategies to make things like molds for precast concrete façade panels. We’re still a family‑owned small millwork company at heart, just one that has grown to 50 people and has multiple CNC machines.

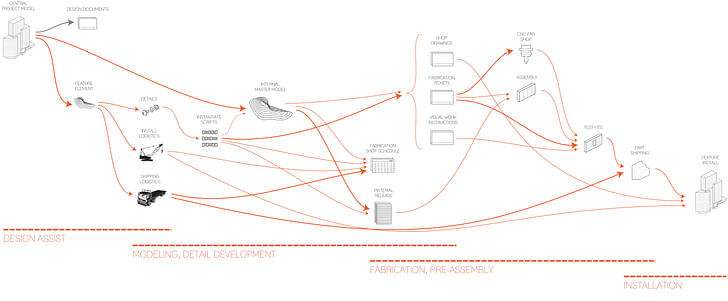

On your website you have a background image that diagrams the workflow at C.W. Keller, showing a design-assist group operating in parallel to the rest of your operations. What’s the scope of work that you’re engage in?

Design assist is a great business tool for developing relationships with firms. With that model a certain client base, whether they be architects or general contractors, brings us in very early on to help with a concept that they're designing.

We partake in a very transparent process that starts with concept model intake and very quickly works out the basic fabrication details, then feeds that information back to the client to show them very basic costs quickly. That allows the client to not go down that rabbit hole of, "We just spent three months designing this, the client loves it, but we got all the bids back and we're 100 percent over budget." It avoids the value engineering process which routinely just muddles the design.

Is the design assist process more of a one‑time sanity check, or is it a constant back and forth with the client?

We like to iterate constantly. We don't want to go off and engineer for four days and then present to the architect and have them say, "Oh, no, that's not really what we're thinking." We'd rather go for four hours and do a quick web meeting and review the model. Then use that feedback to work for four more hours and get back together to review the model again. If we provide the transparency through the design assist process by feeding the information back to the architect to show where their costs are, we find that it's a much more productive relationship.

You have some team members with design backgrounds and others with backgrounds in the trades—how do you build teams that complement and expand upon what each brings to the table?finding people who have strong modeling skills and who also understand what the machines are capable of doing is very difficult.

What we call the Design Engineering Team is part of the sales team. Clients' projects are brought in, evaluated, and to certain degrees go through the modeling process that I mentioned. They're analyzing the scope and doing high‑level studies that we can generate budgets from.

The Engineering Team is made up of people with architecture‑engineering backgrounds and folks who’ve worked their way up from the bench. They’re builders that transitioned to running CNCs, then learned CAD and 3D digital modeling and became draftsmen.

Combining those teams, you have people who are very sophisticated with modeling or Grasshopper scripting working with people who know how the machine's going to behave and what its limitations are. Currently the weak point in the whole system is in the transition of geometry through CAM programming to make the CNC machines do what they need to do. We’ve found finding people who have strong modeling skills and who also understand what the machines are capable of doing is very difficult.

What projects do you have on the boards that you can talk about?

We're working with some clients, like Google and WeWork, at a very high‑level. Those companies are looking at ways to get out of the standard drywall-and-metal-stud approach where they fabricate a conference room and then six months later they’re reorganizing and have to tear all that stuff down.

People aren't building low drywall partitions to create desk spaces—they're buying partitions and kits of parts to do that. The next step is how to do that with walls and ceilings so that you have engineered demountable systems that can be assembled and disassembled in different configurations to make larger spaces.

For large‑scale cast‑in‑place concrete projects, there’s the Sixth Street trestle in Los Angeles. We've just finished an eight-month process of working with Skanska Civil, HNTB (the Architect of Record), and Michael Maltzan's office, who are the design team.

Essentially, we were hired to create a master fabrication tolerance model of the entire three‑quarter mile long cast‑in‑place concrete bridge. That model is being used to create a tool that we can use to develop strategies for the forms to cast that bridge, but also as a tool for all the ancillary subs who'll be involved with erecting the bridge.

Those two projects show a shift away from the onesies and twosies of traditional fabrication work to larger systems development, changing the role of the fabricator and how they’re engaged with their project partners.

I think it will remain a niche market but a growing niche market. Architects, engineers, and designers all want to do projects that are more interesting. They don't want to do rectilinear facades if they don't have to. I don't think you're going to see a transition to everything being done through a design assist process, but there's a lot of building going on and there's a much bigger appetite for this type of process.In the next five years you're going to be able to have technology working in your phone that is going to give you a construction-grade scan.

The industry will continue to go that way, but it does require everyone to change their thinking a little bit. It requires a bit more trust. For us, we feel it requires a lot more transparency in how costs are developed and a willingness to share information. We are continuing to try to find those clients who want to embrace this way of working and try to partner with them as much as we can, and then support them in that process.

The best examples for us are firms like NADAAA, who we've worked with for 10 years. Nader Tehrani understands the value of talking with fabricators. Whether it's us or a metal facade company or a glazing company, getting in and understanding what they do and how they do it informs his designs. He brings that collaboration and information to a lot of the designs that he's doing.

As an early adopter of some technologies, what’s going to be the next big thing for the construction industry? Does anything stand out to you as something that could radically change how things are done?

One technology that we've invested in is forensic-level laser‑scanning technology, which gives us a much better link to a project site today than we had five years ago. Let's say we're doing a big feature ceiling in New York City and that ceiling is just a raw space full of conduit and mechanical ductwork that we've got to work around. We can now laser scan that and create a 3D model of those existing conditions to overlay our fabrication model onto.

Where we see the evolution happening there is the cost of laser scanning is being driven down dramatically. In the next five years you're going to be able to have technology working in your phone that is going to give you a construction-grade scan. We could be scanning as construction happens and have a much more powerful tool for eliminating change orders.

The flipside is CAM in general. It's so clumsy going from a very sophisticated Rhino model that shows every detail, and essentially deconstructing it, laying it into sheets, nesting it, applying tool paths, and running simulations to make sure that the machines aren't going to crash into something. It needs to be so much smarter than it currently is. We're seeing more and more companies like ours starting to get frustrated with the lack of innovation and starting to try to hire people who can work around it.

This piece is a part of the Matters of Scale series, featuring interviews with the innovative fabricators, technologists, and makers giving tomorrow's architecture its shape.

Aaron likes his music loud, his coffee black and his whiskey neat. A designer and technologist in Brooklyn, NY, his current investigations relate to the practical application of computational tools and their intersection with traditional interpretations of craft and technique. Aaron is a founding ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.