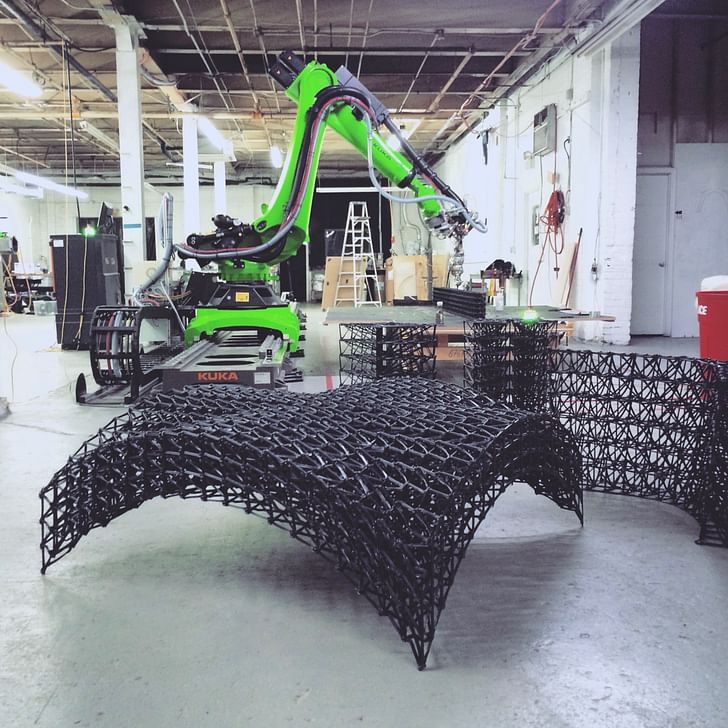

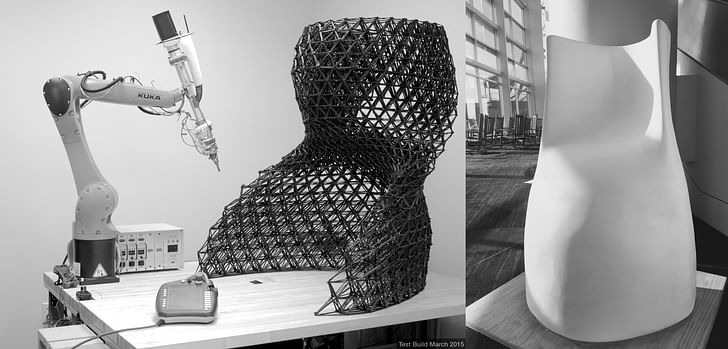

Platt Boyd is the Founder and CEO of Branch Technology, a start-up in Chattanooga, Tennessee that is actively pursuing the intersection of technology and construction. Their Cellular Fabrication (C-Fab) system combines industrial robotics and material science to 3D print a large-scale, optimized lattice system for concrete structures.

In order to source the design for the first full-scale application of their system, Branch recently held the Freeform Home Design Challenge—the winning entry by WATG Urban Architecture Studio will start production in early 2017.

While the technology at the heart of Branch may appear similar to other robotic 3D printing projects, what truly stands out about Branch when talking with Platt is the decision that he and co-founder Christopher Weller made, to take a singular idea that (like most things in architecture) started with a scale model, and turn it into a business. Rather than operating in the general safety of the academic setting where you might expect to find their work, Platt and his team have instead taken on the challenge (and risk) of navigating the start-up world, so that they can develop a construction system that will have a dramatic impact across the entire spectrum of the built environment.

The people I’ve talked to in this series could be described as operating in and around the role of a fabricator. While related, you and your work with Branch stands because of your business model—Branch is a tech start-up. That’s a business model I'm admittedly not overly familiar with—how do you see the operations at Branch differing from those of your run-of-the-mill fabrication or design office?

At Branch what we're doing is enabling other designers, other business owners. We’re creating the technology that allows design to flourish, and allows people to design in much freer ways than they previously would have been able to.Architects get paid a pittance for what they're really worth in practice, and have the skill set for doing things in an entrepreneurial sense that are far beyond what they're doing.

But then to answer the question about being a start-up, it’s a world that I was not familiar with, and have had to learn an enormous amount over the past three years. Initially Branch was just an idea that I worked on during nights and weekends, before I left the firm I was at. Since then I've had to learn all about venture capital, investment, angel investors, and what all the different forms of equity are. That side of business is not what they teach you in architecture school, especially for start-up‑type businesses.

Did you feel that your training as an architect prepared you for the start-up world?

Architecture school and practice are great preparation for something like this. I think architecture is the synthesis of design and logic. When you put a building together, you're coordinating a team of engineers to make something—that's the reality of that building. With Branch, it's just a new technology. It's coordinating a team of engineers to create a new technology, and rather than the output being a building, it’s a platform. Architects get paid a pittance for what they're really worth in practice, and have the skill set for doing things in an entrepreneurial sense that are far beyond what they're doing.

And has moving out of practice into a technology‑based start-up changed your perception of the architecture and construction industry?

I probably couldn't go back to a traditional practice now. There's a lot of other things, especially on the digital design and fabrication side, that I'd want to do before I did that again.

Design as a profession is very undervalued right now, and that's a sad thing. What I would love to see is what has started to happen in product design, where design is not just a commodity, it's the end goal. It elevates design to the end‑all, be‑all. It brings the designer back into the equation. Everything is about how something can be cleverer, or more beautiful. It’s my hope that Branch starts to bring design back into the place that I think that it ought to be. If we can facilitate that in just a small degree, I will feel like this has been very, very successful.It was amazing to see what our community of designers were able to come up with.

With the design competition that Branch organized, did you see any trends in the submissions that reflect how designers view both the current state and inherent possibilities of Branch’s technology?

Absolutely. There were some that were more geometric—faceted and planar. There were some that were organic with very flowing forms. Then you had some that were more invested in modules that fit together like pieces, and then some that were very biomorphic. It was all interesting to see. That's what I love to see, that people came up with different things. It really was about the capabilities of a designer's vision. I loved that; it’s something that was very gratifying.

We were incredibly pleased with the level of design, the talent, and just the thoughtfulness of the submissions. In some cases, they were providing solutions to problems we had never even thought about. It was amazing to see what our community of designers were able to come up with.

What was it about Curve Appeal, the winning project from WATG, that stood out to the jurors that put it above the other submissions?

A couple things about this submission: one, it was these sinuous curves, and beautiful, flowing surfaces. It wasn't just looking at panelization in terms of orthogonal lines, but rather it was looking at how you can seam these things together very organically. It was pushing the envelope on curvature and the capabilities of our technology, working within our current constraints, but then integrating other systems into it very thoughtfully. For example, instead of it having large planes of curving glass, the glass was planar and died into the curves created through the wall systems.

How long do you think it's going to take print that?

It's going to take a while. [laughs]

Just looking at the sheer volume of the project, the print time in itself is going to say something about the viability of this technology.

That's something that we're working on right now. Our speeds are four‑and‑a‑half times faster than they were a year ago and we're still looking to increase those. I'm about 95 percent sure that we're going to get a phase two National Science Foundation grant, where one of the purposes of that is to pay for the testing, and going through the ASTM testing for the load‑bearing assemblies. We’ll know the capabilities of these walls in a load‑bearing sense, and then it can be engineered. There's a lot of background things that have to go on before we ever even start printing and construction. Those are things that we're working on, and that will probably take until February to complete.

If, as a business, the economics don't work, then the technology is useless.We can start printing now, but we have no idea if, performance‑wise, structurally, it would work or not. Obviously, we don't want anything to fall down on our first project. We're going through the due diligence to do the materials and structural testing, and then the engineering of the envelope of the building, before we ever start the printing phase. The construction phase—including on‑site, the prefabrication, and everything—we're looking at about six months for the construction phase.

Then that's for the total. We'll see how that turns out. This is anticipation. Knowing our current speeds, and what it would take, probably about four months print time to do this, which is fairly long in terms of construction. It's all prefabricated so you go on site and it can be erected pretty quickly. It’s like a project we did for a children's play pavilion in a botanical garden and art museum in Nashville. It took us three weeks to print it, but we prefabricated everything, took it over there, and put it up in an afternoon. It comes together very quickly once it's completed. It's just that prefabrication portion of it takes a little while.

Even with four months of printing, I don't know where this falls within all the claims of being the first 3D‑printed house.

It's not the first-first. Hopefully it's the first in the US.

[laughs] Regardless, four months is still really impressive as run times are only going to get better as the technology matures.

It's got to be something where the economics work. If, as a business, the economics don't work, then the technology is useless. It has to work economically. It has to be viable in that sense, otherwise it is just another neat idea that is great in an academic sense, but it doesn't really work in the real world. That's what we're going after—economic viability so that it can flourish and grow.

Outside of that, what do you see as the next territory that Branch needs to look at? You’ve already done a lot of work on the process and the computation. Is it pushing what the materials are a little bit more?

One thing that a lot of requests have been made for is furniture, and that's within our wheelhouse right now. We're actually going to be launching a website in the next couple months for 3D‑printed furniture. It’s lot more accessible than construction, and that way while we're going through the testing phase for the house we can begin doing some things at the furniture scale.

That's what we're going to put our toe into in the very near future, parametric furniture that can be customized for what people want. That's what we're in the process of tooling up for. We'll begin to launch that hopefully in the next couple months.

Aaron likes his music loud, his coffee black and his whiskey neat. A designer and technologist in Brooklyn, NY, his current investigations relate to the practical application of computational tools and their intersection with traditional interpretations of craft and technique. Aaron is a founding ...

1 Comment

If "skeleton for concrete structures" is supposed to be a reinforcing mesh they totally fail. All of those are way too closely spaced and awkward to allow large aggregate to pass through or to even vibrate the forms. They look cool, but have nothing to do with optimized structure. Too bad they get covered up with concrete so you cant see the magical lattice inside. Just call them what they are - cool forms.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.