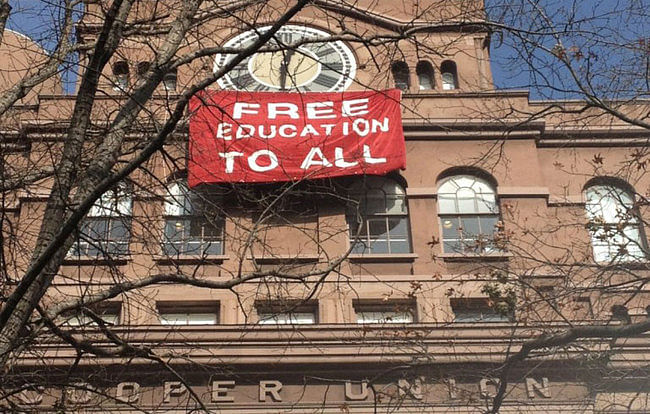

On September 2, students at Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art returned to a school in rocky flux. Faltering under the weight of a $12 million deficit, the New York institution defaulted on its more than 150-year founding tradition, and began charging undergraduate tuition for the first time in the fall of 2014. The decision was a messy one, carrying the baggage of both a financial and identity crisis for the school.

Within the last three years, after first realizing its dire financial straits could mean that the school might have to start charging tuition, Cooper appears to have been tensely simmering, and at times boiling over into public displays or outright legal action. A robust student-led protest movement known as Free Cooper Union, started in fall of 2012, has been staging displays and distributing informational materials to bring transparency to a process that, to many, has felt anything but. Faculty, students and alumni, under the Committee to Save Cooper Union (CSCU), filed a lawsuit against the school’s board, challenging the necessity of instating tuition. Then, as if to add more sour cherries on top of the school’s melting sundae, the school’s president Jamshed Bharucha resigned, directly after five Cooper Union trustees also stepped down.

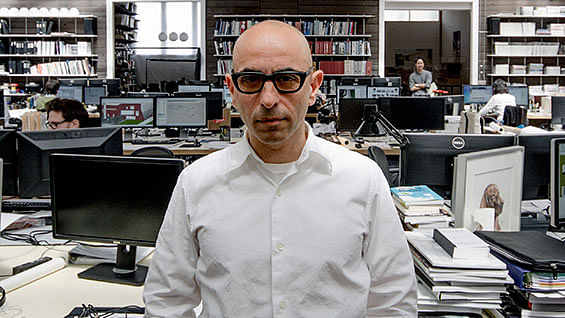

In the midst of this structural tossing, classes (for the most part) continued. Before the decision to start charging tuition was made, school officials including deans pitched alternative revenue-generating models, and attempted business-as-usual in what continues to undeniably be a difficult time for the school. And recently, a light of optimism appeared: CSCU’s lawsuit against the board was settled, after the school signed a consent decree As applications fell in response to the tuition decision and institutional morale licked its wounds, accepting a leadership position at Cooper was not an easy decision.promising to forge a path back to its tuition-free model, among other reforms. It's not a definite, but it's something. But in the midst of all this, from 2013 and up until now, the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture did not have a permanently appointed dean – Elizabeth O’Donnell was serving as Acting Dean, until Nader Tehrani was selected for the position, effective in July of this year.

As applications fell in response to the tuition decision and institutional morale licked its wounds, accepting a leadership position at Cooper was not an easy decision. Tehrani was already working as the head of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning when Cooper first reached out to him two years ago, when the search for a permanent dean began. He initially declined, but was ultimately swayed late into the search, during a meeting over coffee with then-acting Dean O’Donnell: “She made a very persuasive case for the culture of the school, and that I should simply enter into the conversation, which I did,” Tehrani explained to me.

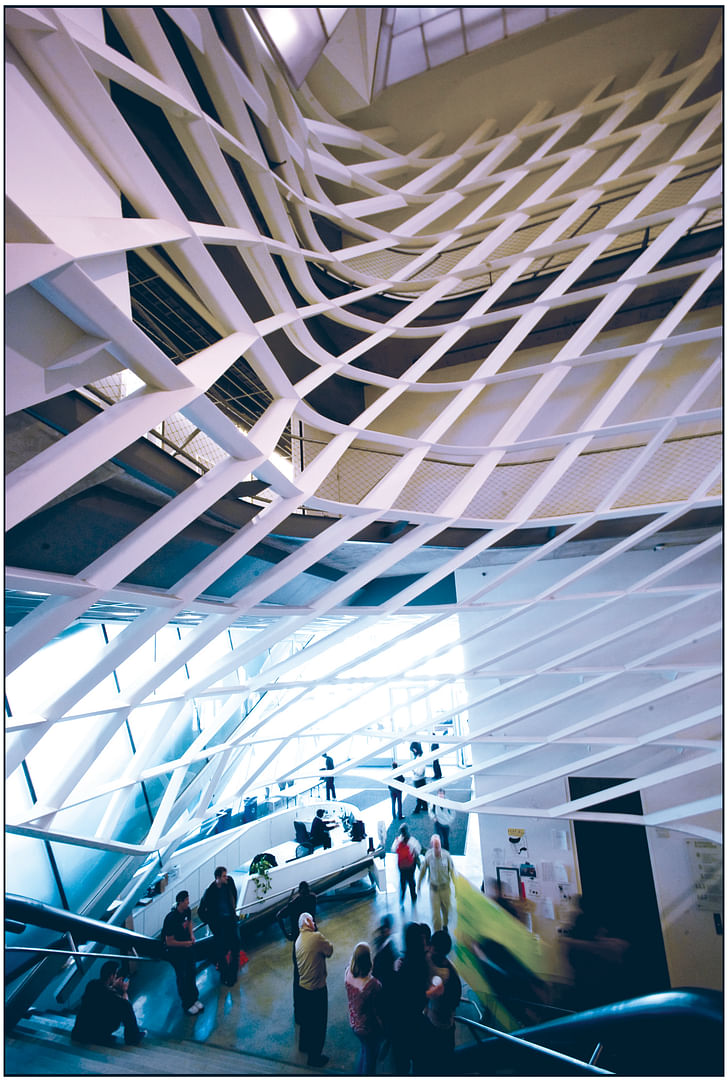

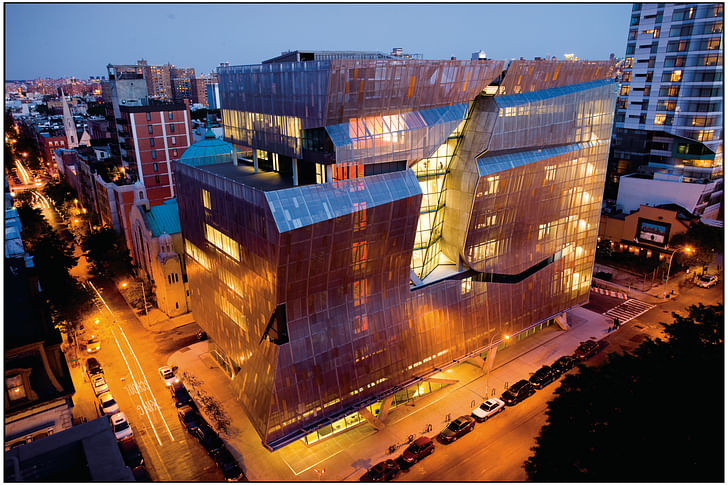

While the school’s culture might seem to be the very thing most imperiled by the tuition decision – as it may drastically redefine the kind of student enrolled at Cooper – for Tehrani, the quality of education remains as it was: top notch. An architecture degree from Cooper, according to Tehrani, comes out of a culture specific not only to the school’s pedagogy, and built into its actual physical architecture. “In the context of Cooper,” Tehrani told me, “you have a very clear identity in terms of the building you occupy: the third floor, the studio space where everybody shares the same space. There’s an incredible culture that is born out of the scale of the school (there’s about 150 students) and the intimacy of its pedagogy.”

That strong, space-based culture has also been used as a protest tool. The same third-floor lobby space was painted black by protesters in response to the tuition decision; a potent expression of outrage and injury. As Tehrani’s deanship has just begun, he admits that “I know the school through its myth, not through its reality.” But he does revere the structured a Cooper Union that’s an open environment for debate, for discourse and competing agendaspedagogy of the school – where instruction is done in groups, and all the studios teach together, “so that some of the productive frictions (that come out in other schools through the autonomy of each studio) here need to be negotiated live, in public, in front of the students.”

Naturally, Tehrani is not setting out to draft a new agenda for the school, but wants to first get under its skin. Undoubtedly at the beginning of a new era, Cooper will have to wrestle with how to carry on its original mission and values in the context of a new financial reality. Tehrani will meet with faculty, get to know students, and has high hopes to “make a Cooper Union that’s an open environment for debate, for discourse and competing agendas,” and perhaps eventually, “we may be able to build some kind of bridge between its legacy and different paths that maybe it has not yet addressed.”

When asked over email what they thought of Tehrani’s appointment, a current undergraduate architecture student (who had been involved in the protests) remarked with optimism, writing that he thought Tehrani would bring a fresh perspective on the balance between academia and practice. A student in the final class receiving full-tuition scholarship (the precise term for Cooper’s “free” tuition) felt Tehrani’s approach to architecture education offered a welcome change from what the student called Cooper’s “academic narcissism”.

Speaking with Tehrani, he also seemed intent on encouraging collaborations with some of architecture’s classic counterpoints. He alluded to a continued development of the relationship with Cooper’s art practice, and a desire to bring that mutually-challenging interchange to architecture and engineering: “Art culture enjoys a more experimental, speculative and critical culture, and architecture has always flourished with a self-consciousness that does not merely appeal to conventions, but also challenges them at the same time. However, I don’t think that the culture of architecture and engineering have been able to feed off of each other to the same degree at Cooper.”

And the Cooper Union certainly isn’t alone in a renewed scrutiny towards architecture education’s inherent value. New initiatives, such as the Architecture Lobby and the London School of Architecture (to name just two prominent players) have formed, in part, explicitly to critique the cost of being an architect in today’s economy and culture. The Architecture Lobby advocates for an elevation of the architect’s value, both within the discipline and in larger society. The LSA is an entirely new institution, built on a “cost-neutral” model that bears a certain family resemblance to Cooper’s founding principle: “open and free to all.”

Cooper must find “what is indispensable in architecture, and how do you make that the ingredient of speculation.'The same undergraduate who expressed optimism towards Tehrani’s tenure remarked that already, the school’s community had started fraying around the perceived haves and have-notes. Students surfing the final wave of the full-tuition scholarship began questioning the merits of those new students who paid. "What kind of architects will come out of Cooper now?" they wondered. To Tehrani, the difficult calculus of value (both monetary and otherwise) and merit will ultimately determine pedagogy. Cooper must find “what is indispensable in architecture, and how do you make that the ingredient of speculation.”

”As a practicing architect, Tehrani is no stranger to the fluctuating climate of the profession. While recognizing his role as dean is separate from that of a designer, his foot in practice as the principal of the award-winning firm NADAAA (ranked #1 in design by Architect Magazine for 2015), which is based in Boston and New York, will help contextualize his strategy for programming. And just as the stresses and trials of practice make architects stronger, so can Cooper’s internal struggles: “If any school can shine so well under these circumstances, it means it must be the best possible position in the world, so that’s part of the reason that I’m here. I think it’s fantastic.”

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

4 Comments

Yet another white male architect speaks and we are suppose to be enthralled...

I don't think many Iranian-Americans would consider themselves white...

yeah, but his shiny bald head and bulky black frame glasses are SSSSOOOOOO dreamy i could just MELT

The dismissal of someone based on their race and gender is as laughable as the endorsement of someone for the same qualities.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.