For the past few months, we’ve been publishing parts of an extended conversation with Denise Scott Brown. In this installment, we delve deeper into our discussion of the pedagogical methods employed in the Learning from Las Vegas studio, and what ‘learning’ should mean for architects more broadly.

Tell us about the Las Vegas studio.

To study Las Vegas we needed methods as unusual as the city itself. In the last installment I described how the theories courses that Bob and I taught architects at Penn helped us evolve the Las Vegas studio. Other sources were courses and studios that I took and taught in Penn’s planning school, 1958-64.

For both schools, bridging from coursework to design was a struggle and studio was its main arena. Planning schools agonized over the connection, but in architecture the studio critic's credo was the accepted subject matter and attempts were not made to connect courses to design through studio.

For these reasons, the bridges of our theories courses came from planning. But I knew that to engage architecture students in facts and research we must find a project whose artistic possibilities would intrigue them, one they could grow passionate about. Then we must make the research indispensable to the design they were aching to do, and plan its tasks to challenge their creative initiative. And for 1960s students, only a rebellious artistry would intrigue. It had to "blow the minds of the citizens". We agreed. And if our aim to widen their view of architecture called for a measure of rebellion, so be it. It would be fun. Voila Las Vegas!To study Las Vegas we needed methods as unusual as the city itself.

But the neon city strained our bridges. We had devised them to connect architectural history and design, two fields that shared a focus on buildings and had a long history of collaboration. Yes, our bridges could make connections to architecture’s traditional support fields—"Not so well!" historians and studio critics might say—but most architecture students had taken undergraduate courses in history, and some architects, like Bob, knew architecture and history and could show ways via his own work of relating them.

The social sciences connection was much harder, despite the place of social concern at the heart of the Modern movement, and the misty but great-hearted desires of the 1960s to serve humanity through architecture. 'Dogoodism' the social planners called it, warning that unsophisticated efforts could have harmful results.

Through discussion with city planners from the social sciences, but especially with social planners and urban activists, I developed ideas for connecting architecture and social forces, the natural world, and urban technological systems. Those were great days and, though Penn planners and I fought tooth and nail, I felt that, Bob apart, they were my true colleagues, the ones I was nurtured by.* Dave Crane pointed me as well to the quieter waters of Regional Science, an economic discipline. I took the introductory course and audited the further thinking of Walter Isard, guru of the program. We too became friends.

As I began my parallel teaching in architecture and planning I defined my task as bridging. I was a circus horse rider between two fields that were pulling apart. In urban design studios I tried to help students confront urban subject matter they knew little about, to make it part of their design selves, and to use it as architects, not social or natural scientists, or engineers. We needed to interpret their material in our ways.

My Form, Forces and Functions, FFF, studios proposed that long before architects arrived, social forces, natural conditions, and technologies made the patterns of settlement and the forms of cities, and that they continue to do so as we design. It's no use ignoring them. So what then does form follows function mean and how should it apply?

Why do they do it, why there, and what do they need there?In architecture it refers usually to uses in spaces inside buildings, and these are the functional relationships we teach architects to support while designing. Ask “but what about outside relationships and outside design?” and Modernists would reply that outside form results from inside activities, and only formalists would interfere in that relationship. But Corbusier who, perhaps apocryphally, told his clients, "the outside doesn't concern you," meant it concerned him. He wanted to ensure it would be a cubist play of solids in light.

Architects design from inside out and outside in, and sometimes they twist the inside to get what they like on the outside. But here we have other fish to fry—external functional relationships should and do affect the outsides of buildings but we architects learn nothing about them. Consider how students sit about at entrances of academic buildings, waiting, working, sunning themselves, meeting and chatting, opining and sometimes orating. Why do they do it, why there, and what do they need there?

At the doorway, room is required for crowds simultaneously entering and exiting between lectures, plus a place to see the building name, read information posted there, perhaps shelter from rain, and gauge what they can from the architecture of the front door. The numbers and sizes of groups taught inside determine crowd size at entry and the space required to hold them. And immediately inside, space will be needed to stop, read signs and choose routes. Until it disperses, the crowd needs equivalent space inside and out. So entry requires a pretzel-shaped space.

Pretzel-shaped?

Yes, the space spanning the doorway—and an architect who understands the physics of crowds. Now go one step further. If there's a comfortable coffee shop in the building next door, people may hang out there after the lecture, get arguing about it, and perhaps find that discussion more valuable to them than the lecture. A faculty member with an hour between classes may read term papers, or encounter a colleague and serendipitously take the first steps to a new invention.

Expand the idea. If the coffee shop is located at the crossing of major pedestrian ways and draws passersby and people from activities near and far, it can help to create a meeting of minds and a marketplace of ideas. Universities and colleges try to set up patterns of activities and circulation that support such linkages.

"I love your site analyses" an architect tells me. Put it that way, I reply, if this makes it interesting for you, or call it functionalism of the outside, but realize that although it starts at the front door, it reaches to the city, the region and the many-scaled relationships of our projects with the world. Until we broaden our understanding of these, we will continue to make projects that disrupt social patterns and break linkages.

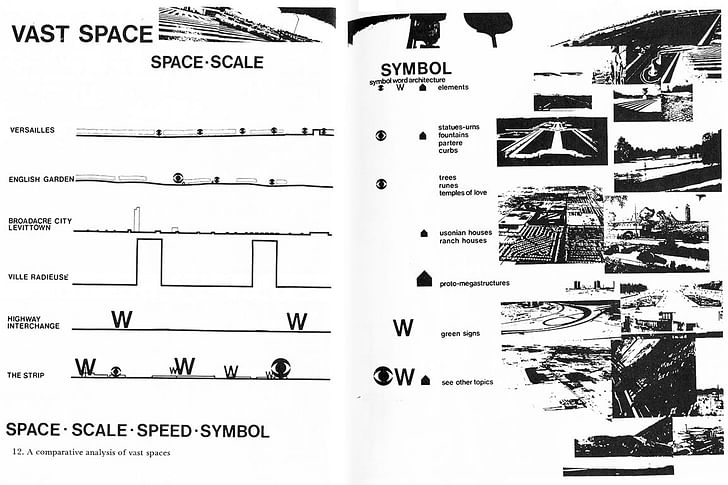

But broadening isn't as simple as mapping. Land use maps of Las Vegas, for example, miss highly noticeable objects of the city—its signs. They don't read on land use maps. Mapping information is important and can be fun. For example, locating on a plan all the disciplines studied on campus produce fascinating patterns, and faculty discussion regarding where, say, math should be taught, can range delightfully across disciplines and dispositions.Dictating it by design, by an act of will of one architect, is not adequate.

But at the end, although you know the needed relationships of one discipline to others and something of their intensity and possibilities for growth, and although you comprehend mapped information, forces at work, and the goals and policies of users and constituents, you don’t understand how the interplay of all these settles on the land.

Dictating it by design, by an act of will of one architect, is not adequate. And though we accept that the middle F in FFF comes before Corbu or us, knowing those forces but not the rules for their combination leaves us where we are now; basing urban design decisions on the needs of the inside uses of buildings, but depending for the outside relationships on credos and aesthetics, not knowledge.

To write, you need ideas but also vocabulary and grammar. To design in an urban context, you need urban models that explain, not just patterns of settlements, but how they form—how attractions and repulsions among elements of the project and its context generate and regenerate patterns. Imagine magnets under a tray of iron filings. As magnetic force draws the filings, patterns of gravity and potential develop, and on a flat surface they are not distorted by other factors.

Regional science, nicknamed ‘city physics’, gave me the second bridge I needed to link to more than architectural history and explain the forces behind the patterns. It's an economics discipline, a theory of location that relates economics to land in a ‘space economy’, taking into account activities, capacities, distances, circulation, and more, and hypothesizing the rules of their interaction in a model that generates land values, settlement patterns, and growth over time.

The math of the models is a black box to me, but the principles are understandable. And as with structural engineering, architects should be able to grasp and use them imaginatively. Indeed, as architects and, by definition, holistic thinkers, we may even spot stupid assumptions in the models.

But forefingers, our own digits, can be simply crossed to represent intersections of routes, from wagon paths to regional interchanges. Here, where most people pass, marketplaces form in every culture. And from here settlement grows in a gradient according to values assigned to activities by users, and following the law, "here is nearer than there".

Map land values, or their equivalents in rent, to form contours, whose heights rise and cusp in ‘rent tents’ around major crossroads. They parallel the density patterns of the city and suggest its form—one big center or multiple small ones depending on, among other things, forms of transportation. The rising heights suggest the increasing rents people will pay for property as it nears the rent tent cusp, the ‘100% point’, at or as near as possible to the crossroad center.

The many reasons for the form of Manhattan include hard bedrock, the invention of the elevator and the typewriter, and the entry of women into the workforce. But its early 1960s skyline seen from the Staten Island ferry, was cusped like a giant rent tent. This reflected the introduction of regional train systems with stops that decanted the workforce at the center of the island, from where walking was the only option until mass transit came. Hence the skyscrapers and retail emporia that sold everything to everyone.Stand bravely at the helm forever and you’ll go down with the ship.

So land values and rent patterns parallel and sometimes predict the form of the city. They lay graphs on the land that economists enjoy, hypothetical filigrees of evocative beauty that could be our Muse. And their information is potent. When I asked students in Las Vegas to request land value figures to map, they were told, “If you had that map you’d be the most powerful person in this city”—a graphic illustration of the fact that settlement patterns and forms result more from decisions in a market economy than by fiat of sovereigns.

You can argue that markets in land are a fault of capitalism and should not exist. But all political systems must reckon one way or another with the forces of attraction and repulsion that act and compete in land use and development. The question is how to see them as an architect? We consider ourselves team leaders, master planners, captains of the ship. We are workers against the forces who, through the strength of our art, can make water run uphill. And we can, if we are excellent engineers. But not often. There is only one Jet d’Eau in Geneva and one Central Park in Manhattan. Stand bravely at the helm forever and you’ll go down with the ship. But be a wily surfer and you may choose a wave and take it to or near your destination.

So fight the forces and/or use them, but know them. Know “city physics” because it takes us from forces to physical patterns to forms—where we need to go, and in ways related to what we do as architects, ways not offered by other social sciences. It is our bridge. And after fiats and power plays have had their say, it informs the decisions of smaller businesses and owners, of “the city of a thousand designers”, as Crane called them, as they reassert themselves and regrow the patterns around intrusions. College town plans show how town and gown play this game.

There’s much architects can do with this information. It’s understandable without math but with a feeling for structure, urban, natural and architectural. And without it we risk being chasers of false visions, designers of projects that disconnect and don’t reconnect social and physical tissue—being part of the problem.

*Check out Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi's bibliography here, which contains information on works written about and by them. For more information on the writers specifically referenced in this interview, see the bibliography at the back of Architecture as Signs and Systems, where Scott Brown made selections of books and articles of Crane, Isard, Smithsons, Gans and others that she had found useful.

Get caught up with part 1 and part 2 of our conversation with Denise Scott Brown.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.