What is the role of education in shaping a visionary architect? Several contemporary architects reflect on how the environment, curriculum, and tangential opportunities of their formal learning influenced and shaped their design sensibility.

Rem Koolhaas

Rem initially trained as a journalist, conducting avant garde interviews that included no questions but simply confronted subjects with a large microphone. His immersion in media and a brief foray into screenwriting stuck with him. As he told Spiegel Magazine, “In a script you have to link various episodes together, you have to generate suspense and you have to assemble things—through editing, for example. It’s exactly the same in architecture. Architects also put together spatial episodes to make sequences.”

He eventually enrolled in the AA School of Architecture in London. As he recalled in Exodus, or the voluntary prisoners of architecture: “THE SCENE. London’s Architectural Association 1970-72: a school awash in sex, drugs and rock and roll. David Bowie hanging at the bar; flash to a person with experimental hysteria quickened by a school awash in sex, drugs and rock and roll the visionary projects of Archigram, architecture’s answer to the Beatles; galvanized, sort of, by the European action politics of May 1968; intoxicated by the spontaneous American Love-urbanism of Woodstock and its shadow, the erotic violence of Altamont: edified by the froth of the rumors of French intellectual thought; drawn to design, to mod and Carnaby Street, and to antidesign, to the swagger of the infinite cities of Yona Friedman and Italy’s Superstudio and Archizoom. Anything goes, everything goes. For studio, write a book if you want. Dance or piss your pants if you want. Structure or codes or HVAC? Go to Switzerland.”

While there, his propensity for being unusual and brilliant landed him traveling fellowships, out of which he would develop the ideas for his groundbreaking work Delirious New York. His attitude toward education reflects his multi-faceted, all encompassing approach toward his work. In an interview with Dezeen discussing how he met Zaha Hadid at the AA in the 1970s, Koolhaas noted that: “Nominally, I was teaching, but at the time I think the difference between teaching and learning was not particularly noticeable.”

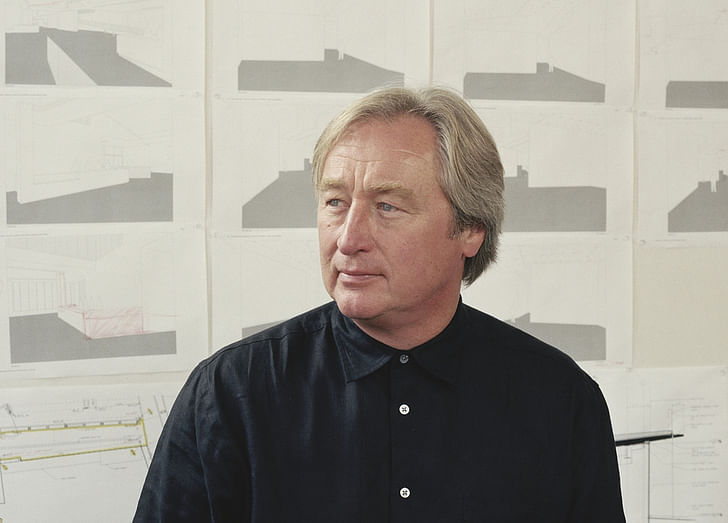

Steven Holl

Steven Holl’s remarkable work springs as much from his perennial desire for discovery as much as it does from his love of mixing mediums. In the Steven Holl Architects/Simmons Hall monograph, Holl says that “I think the first moments of your education are the most important, just like your first job. It is where you form your value system and build a way of working. I think the first moments of your education are the most important But I was in this suburban office doing terrible projects—men’s shops and things like that. I did not last there very long. The following year, I went to San Francisco, to begin.”

As to his official education, Holl recalls: “I went to architecture school at the University of Washington. There I studied the works of Schinkel, Sullivan, and Wright under Hermann Pundt, an incredible teacher and a great inspiration. At his urging, I spent my junior year in Rome working with another incredible teacher, Astra Zarina, whose insights revealed to me architecture’s inseparable intertwining with culture. The trip was a sort of architectural shock therapy. I had never been out of the U.S. before, never even to the East Coast; and I suddenly found myself in a plane flying over the North Pole, traveling from a place of zero architectural significance to one of maximum historical density.”

Bjarke Ingels

Bjarke’s seemingly oversized enthusiasm and goofiness allows him to envision projects that are both media-friendly and architecturally adventurous. It wouldn’t be a stretch to describe his designs as verging on the cartoonish. Suitably, in an interview with TedX, Bjarke speaks about how his education enabled him to transform from an aspiring cartoonist into an architect:

“I thought that the School of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts was a smart way to get some drawing skills. But then I got interested in architecture. Of course, I had no clue about architecture. I knew of Jørn Utzon, the architect of the Sydney Opera House, and the engineer Gustave Eiffel of the Eiffel Tower. My architectural knowledge pretty much stopped there. So when I got into architecture, I thought that architecture was all about form. Slowly I realized that behind form there’s a concept – the result of how you choose to organize life and activities in the building. It’s the same with cartoons. You deploy the images in sequence and there’s a composition to communicate the story that you try to tell.”

Liz Diller

Liz Diller of Diller Scofidio + Renfro has long refused to treat architecture as a means of problem solving, preferring instead to engender thought by “making problems.” In an interview with The New Yorker, she revealed with pride that for years she refused to tell her parents if she had graduated with an actual architecture degree, partly out of childish rebelliousness and partly because she found the profession at the time to be hostile to creativity and didn’t want to own up to being an official part of it. While at Cooper Union, she encountered several professors who would help unearth her contrarian and unconventional design sensibility, notably Ricardo Scofidio and John Hejduk. As quoted in Diller Scofidio + Renfro: Architecture After Images, Diller described Hejduk’s teaching style accordingly: “Just as his statements must be interpreted, surfacing as they often do through the riddle and parable of the raconteur, his strategy to nurture the independent mind of both student and teacher is equally indirect. It is Hejduk that constitutes the school’s most subtle and pervasive paradox: for, he is a leader that cannot be followed.”

Diller has carried this kind of half-opposed, half-welcoming attitude to education into her contemporary practice. As she told Archinect: “I tell my students, ‘Don’t give up!’ You’re examples of how it could work. Basically, when I left school, I had no intention of being an architect. You could never get anything done. Film was pretty interesting, you could contribute in a serious way. Anyway. Architecture changed my life. So I like to do lots of things at the same time. Lots of different media. Architecture is really, really important. It affects everybody else’s lives in a permanent way. Coming from film, wanting to do films, it was a pretty big step for me.”

Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry has made a name for himself by being unafraid to pursue his vision, even when other people think he’s nuts. In Barbara Isenberg’s Conversations with Frank Gehry, the architect remembers how his early educational experiences led him to understand what he was really supposed to be doing with his life:

“Two of my USC professors, the landscape architect Garrett Eckbo and Simon Eisner, who taught city planning, knew my liberal political do-gooder leanings, because they were like that. They also knew I wasn't interested in doing rich guys’ houses and that I would be more emotionally inclined toward low-cost housing and planning. They urged me to apply to Harvard Graduate School of Design and recommended that I take graduate work in city planning.

Mr. Gehry, you have completely ignored the problem I've given you. This has nothing to do with this class.Would you please stop?I didn't know what it entailed to study city planning...The city planning class, the so-called design class, was run by Charlie Eliot, who was the grandson of the president of Harvard [1869-1909]. He was an administrative planner, and design was not his thing. He had us do research on how the cities and towns around Harvard were run, and then he'd give us problems to solve on structure and other things that were scintillatingly boring... So when our final project was to come up with a master plan for Worcester, Massachusetts, I thought I could finally do what I wanted to do. I approached it like an urban design project, figuring out the ring roads and the parking and making an urban center, like I studied at Gruen’s... When it was my time to present... Charlie Eliot stops me and says, ‘Mr. Gehry, you have completely ignored the problem I've given you. This has nothing to do with this class. Would you please stop?’”

Shortly thereafter, frustrated and angry with Eliot, Gehry transferred into design studies.

Jeanne Gang

Massive, politically tricky projects form a substantial portion of Jeanne Gang’s portfolio. An architect who regularly takes on scenarios that sound almost ridiculous (reversing the flow of the Chicago river, anyone?), Gang owes some of her success to her ability to effectively communicate complex concepts to diverse, large groups. I owe a lot to the GSD, the people I met here, the teachers, and my thesis, which still resonates in the things that I work on today.Described by Rory Hyde in Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture as a “professional generalist, who has enough general knowledge to know what specialist disciplines to engage, the skills of communication to extract their expertise, the ability to identify the value in this niche knowledge as relevant to the task, and the extraordinary capacity to synthesize it into an integrated whole,” Gang’s penchant for communication was undoubtedly developed in her school days at Harvard’s GSD.

She noted in a talk given to her alma mater: “I owe a lot to the GSD, the people I met here, the teachers, and my thesis, which still resonates in the things that I work on today.” In an interview with The New York Times, she noted that she had landed a commission after meeting with a developer at an alumni function. When asked if this was a strategy of hers, she replied:

“Go to all your alumni functions, yeah. Actually, that wasn’t a strategy. I think we were introduced by one of my former clients. Being there is important, being involved. Taking a position and being an activist. All those things put you into relationships with other people. It’s an ecology of meetings and issues and talents.”

Thom Mayne

An idiosyncratic talent who initially had trouble communicating his groundbreaking ideas in anything other than built form, Thom Mayne was in a constant state of confrontation with his education, especially when it came to engaging with learned authority figures. After graduating from USC, Mayne sought other experiences. As he explained to The New York Times, “I soon realized policy and planning were not going to work for me. I needed more tangible resolution.” Mayne started teaching abroad.

As he related to Archinect, “I started out as a 26 year old, 27 year old guy, teaching, already traveling to London, and traveling to Japan and teaching and lecturing. It was the shift from Los Angeles from a provincial place, from Ray Kappe, etc. Only Frank [Gehry] escaped that, of his generation, and understood that it got global, and L.A. was this incredible hotbed, probably the singular place in the world in the U.S. I had Pierre Koenig and Sariano and Gregory Ain and these incredible teachers, all of which we rejected of course, that was our job at 19, 20 years old.”

This feature is part of September's Learning theme, considering architectural pedagogy, psychology and lifelong education.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

1 Comment

Diller described Hejduk’s teaching style accordingly: “Just as his statements must be interpreted, surfacing as they often do through the riddle and parable of the raconteur, his strategy to nurture the independent mind of both student and teacher is equally indirect. It is Hejduk that constitutes the school’s most subtle and pervasive paradox: for, he is a leader that cannot be followed.”

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.